Eric Noah Feldman

Everyone Cheats

ISSUE 4 | THE PROGRESS OF MEMORY | MAY 2011

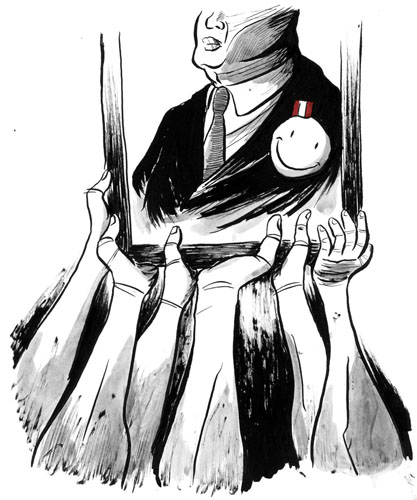

Illustration by Tom Tian

Despite the ban on alcohol sales in honor of the upcoming presidential elections, I was presented with a caustically intoxicating Pisco Sour as I sat at the table. I held it up, questioning the propriety of egg whites in cocktails and the incredible ease with which I had circumvented the stay on booze. The waiter could see my gringo sensibilities being challenged and in choppy but passable English gave me a few words of advice. “Don’t worry,” he laughed, “everyone cheats.” Clearly I had a lot to learn about Peruvian culture.

During the summer of 2006, I left behind the relative safety of a half-gentrified neighborhood in Washington, DC to live in Lima, Peru. I should probably have done more prep work before getting on a plane, but the uncertainty excited me. I stuffed a few shirts in a bag. I found a temporary apartment through Craigslist. Once I scribbled its address onto a folded up piece of scrap paper, I put it in my pocket and headed for the airport.

Armed with a shrink-wrapped Lonely Planet travel book, I arrived in South America without the slightest knowledge of Peruvian current events. As it turned out, my first weekend in Lima was the lead-up to a hotly contested run-off election featuring politicians I never heard of and campaign promises that would never affect me personally. In fact, the weekend-long ban on selling alcohol was the only direct impact I felt from the political drama.

The government’s belief that a sober country would make a more responsible electoral decision caught me somewhat off guard. I had imagined South America as a lawless jungle, replete with non-stop partying and umbrella-capped drinks. In my head, every day was Carnival and women danced in the streets in colorful outfits, twirling flags and flinging beads towards an ever-cheering crowd of tanned revelers.

In lieu of twirling flags, I was distraught to find a buttoned-down conservatism; in lieu of flung beads, rosaries. And what of the bare-breasted goddesses who would call to me with rolled R’s and outlandish hand gestures? They wore dowdy housecoats and whispered about political intrigue.

The only person I knew in the country was a plucky firecracker from Southern California named Kate who introduced herself to strangers for fun. She seemed confident that despite the elections we could still find some enjoyable nightlife, so I put on a fake smile and accompanied her to a jazz club downtown. I readied myself for a quiet evening spent staring soberly at strangers.

We ignored everyone’s advice to stay away from unlicensed taxis and hopped in the first unmarked late-model Hyundai we could flag down. At least the cabs are cheap, I told myself between drags on a loosely packed Lucky Strike. And they don’t care if you smoke in the car. I had more faith in Kate’s Spanish than in my own and appointed her my de facto representative to the outside world. I had honestly believed that I would easily dust off the thousands of verbs and conjugations I locked away without use since the end of high school. It was, in hindsight, misguided.

As we drove on in silence, I noticed that Lima felt no less safe to me than the streets of Northwest DC. My parents’ Are you fucking kidding me? reaction when told that I was moving to Lima for the summer seemed somewhat hyperbolic. The Shining Path, a Maoist rebel group that terrorized the country throughout the 1980s and ‘90s, was all but wiped out. Still, I couldn’t help but feel that if my mother knew I was in an untraceable gypsy cab racing breathlessly through Miraflores, Lima’s richest business district, she would have coded on the spot. She might recall hearing about the Tarata Street bombing fourteen summers earlier, and imagine eighteen hundred pounds of dynamite erupting in a deafening blast, killing dozens and wounding hundreds. In her mind, she would see devastation: buildings without faces, distorted girders bending limply askew, char where there were once desks.

But all I saw were Italian restaurants and supermarkets, and I knew nothing of Tarata Street. By the time I got to Peru, the Shining Path focused less on domestic terrorism and more on smuggling coke through the verdant Selva to the east. The country still bore the scars of the decades-long struggle against these revolutionaries, but the political environment had become far less turbulent than in years past.

After some confusion about our ultimate destination, we managed to arrive at the music club Jazz Zone, pronounced yazzone by the locals. Sheets of sound bled out of the windows and into the streets. Forced to duck through the tiny entranceway, I lifted my head as I entered to find a vibrant party scene: lively conversation, English and Spanish melting together amid the milieu of flutes and drums.

Waiters spun around corners, laying down drinks by the tray-full as they sliced through the crowded dance floor.

If this was Lima’s version of prohibition, I was behind it one hundred percent.

With an impish Hi! Kate struck up a conversation with some strangers nearby and we were soon invited to join them for a drink. The waiter never asked what we wanted. He just planted two Pisco Sours before us as if there were no other drink on the menu.

Everyone cheats, he told me.

Finding myself among some well-informed English speakers, I opened the floor to discussion about the elections. Their general sentiment towards the political climate was negative, to say the least. The remaining candidates in the upcoming run-off election were two of the very men who kept the country in chaos throughout the 1980s and ‘90s. On the one hand, voters could chose Alan García, who as president in the late eighties presided over the country’s economic meltdown and the unchecked rise of the Shining Path insurgency. On the other, the populist candidate Ollanta Humala, famous for leading a military coup against the government in October 2000 and rumored to have committed a number of atrocities during his military campaign against the Shining Path in the 1990s.

Peruvian voters were not exactly spoiled for choice.

I learned that García’s political career started with great promise. After his election to the Presidency in 1985, some hailed him as Peru’s JFK, an image he would quickly destroy. Under his leadership, Peru defaulted on its debt payments and inflation rose to a gut-wrenching 7,500%. The government could barely feed its people. Its ineffectiveness inspired the Shining Path movement. After he lost the next presidential election, García fled the country amidst mounting accusations that he embezzled millions from his own government. Once the statute of limitations on any corruption charges against him expired a decade later, García reappeared to run in the 2001 elections. He narrowly lost in the run-off.

Humala lacked García’s past political experience, but he made up for it with fiery rhetoric that mobilized the nation’s poor. His populist platform, “Agua Por Todos” (“Water For All”), was emblazoned in red paint across the country’s poured concrete half-walls. He buried rumors of human rights abuses committed during his military campaigns against the Shining Path and aligned himself with Venezuela’s Hugo Chávez.

In short, I was able to gather that both candidates managed to piss off a lot of people.

Five feet from the marimba-heavy jazz hooks and the clatter of two dozen twirling feet on the hardwood, I strained to hear the locals lament the political landscape with stoic resignation. While many of the patrons hated Alan García for his past failures as a president, they couldn’t bring themselves to vote for Humala. They called him a monster between cigarettes; they cursed him between shots of grain whiskey.

The more I listened, the more I realized García was getting the majority’s vote, albeit grudgingly cast. Many of the Lima elite muttered angrily about the absence of Lourdes Flores from the run-off election. The right-of-center, business-friendly congresswoman brought the promise of economic reform to the upper classes but failed to inspire the populist vote; she lost the second run-off spot to García by a question-raising half a percentage point. Unable to bring itself to vote for Humala, Flores’ base threw its cautious support to García.

It was enough to secure his victory.

Streets were closed for García’s inauguration a month and a half later, and members of his left-leaning party, APRA, set out a moderate level of pomp and circumstance to mark the occasion. Riding his borrowed votes to victory, García called his campaign a victory for the country of Peru and a rejection of Chávez’s influence. García’s constituency applauded with reluctant fanfare, then returned to their normal routines.

The nervous fervor of the days leading up to the election faded, along with the thousands of posters still plastered onto every available inch of wall space. As I traveled throughout the country in the weeks following García’s victory, I noticed the candidate’s names and faces slowly peeling off the nation’s edifices. Rain made soggy ribbons of the placards but etched ineffectively into the spray-painted campaign promises of the losers. Makeshift campaign centers boarded up their entrances and once again became empty storefronts, their papered windows hiding the piles of undistributed pamphlets and buttons within.

And so the summer passed with politics never again as fiercely discussed as it had been during election weekend at Jazz Zone. When my time in Peru ran out, I locked up the memory of the election next to the pluperfect tense and placed them gently into storage for another day.

Kate and I still talk fairly regularly, but she continues to introduce herself to strangers for fun in Northwest DC while I hide in the bourgeois anonymity of New York City’s West Village. My time in Lima is far enough gone that I don’t think about Jazz Zone when I crowd into the Village Vanguard. I don’t fantasize about ordering a Pisco Sour while leaning on the shabby couches at Fat Cat on Latin Jazz night. But now, five years removed, Peru faces another electoral cycle. Kate pops back into my life with a simple email, forwarding on the news that another run-off is in the works. Once again, Humala is one of the two remaining candidates.

Humala’s severe populism has reportedly softened since he lost in 2006, but his past affiliation with Hugo Chávez still raises serious concerns about Peru’s social and economic future. Although popular with the nation’s poor, Humala makes the middle and upper classes nervous with his radical plans for market reform. He made a last-minute promise not to nationalize the country’s thirty billion dollar pension fund but still aims to rewrite the nation’s constitution to increase presidential power. News outlets slam him for his unpredictable double talk, and it seems near impossible to parse out which promises Humala means to keep and which he is just making to pull in the votes of the undecided.

Running against Humala is Congresswoman Keiko Fujimori. Many Peruvians fear that Fujimori would follow in the footsteps of her father, former president Alberto Fujimori, famous for his corrupt, authoritarian regime in the 1990s. Some even assume that Alberto would run the country from his jail cell through his daughter. While Peru’s free market economy might remain safer under Keiko’s rule, the fear of a return to cronyism and corruption keeps potential voters at bay.

Just like in 2006, the people must make an unenviable selection between two regrettable candidates. Peruvian writer Mario Vargas Llosa reportedly described picking between Humala and Keiko Fujimori as a choice between cancer and AIDS.

Sitting in my cramped Bleecker Street sublet, the words everyone cheats echo in my head. Perhaps Peruvians needed to cheat their way around the alcohol ban, to flout the rules and celebrate the evening as a way to combat the dire atmosphere surrounding the election. Rules are meant to be broken, but the ongoing cycle of disappointing presidential candidates doesn’t seem to be breaking any time soon.

I wish that I could hop into a cheap, unmarked taxi and wallflower at a downtown Lima hot spot. I want to park myself five feet from the marimba-heavy jazz hooks and the clatter of two dozen twirling feet on the hardwood and strain to hear an explanation of why Peru must once again choose the lesser of two evils. But my time in Peru ended years ago, and for this election cycle my knowledge comes from third-hand reports discovered by Google searches. Despite the distance, I can only assume that a sense of stoic resignation once again permeates the hearts and minds of the strangers I once shared “banned” drinks with at the Jazz Zone, half a decade past.

The Hypocrite Reader is free, but we publish some of the most fascinating writing on the internet. Our editors are volunteers and, until recently, so were our writers. During the 2020 coronavirus pandemic, we decided we needed to find a way to pay contributors for their work.

Help us pay writers (and our server bills) so we can keep this stuff coming. At that link, you can become a recurring backer on Patreon, where we offer thrilling rewards to our supporters. If you can't swing a monthly donation, you can also make a 1-time donation through our Ko-fi; even a few dollars helps!

The Hypocrite Reader operates without any kind of institutional support, and for the foreseeable future we plan to keep it that way. Your contributions are the only way we are able to keep doing what we do!

And if you'd like to read more of our useful, unexpected content, you can join our mailing list so that you'll hear from us when we publish.