Brandon Hopkins

Micro-Politics: The Hidden Battle Against Internet Censorship

ISSUE 2 | BREAKING THE LAW | MAR 2011

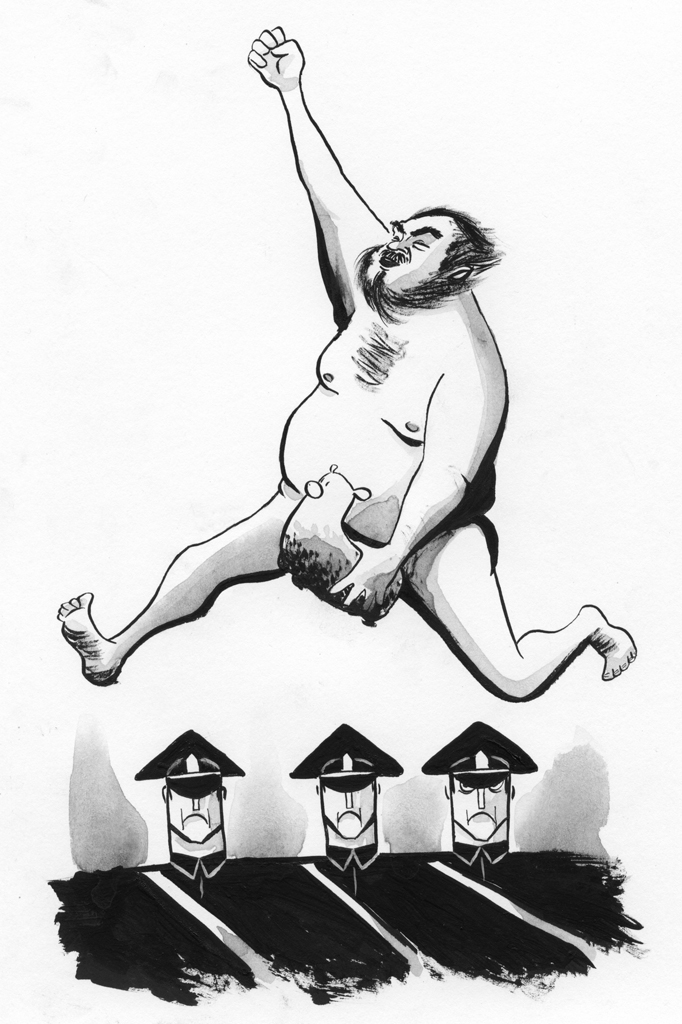

Illustration by Tom Tian

Memes are commonly thought of as fads or inside jokes of microbial scale that worm their ways through an organic system—such as the internet—while evolving from slogan to crudely Photoshopped image to video while maintaining some basic DNA. Even when this DNA is a trivial and arbitrary substance, memes can be as powerful as computer viruses. In America, they have turned normal people into overnight celebrities, sometimes damaging lives, and become a marketing industry cliché. And in their attempts to penetrate the online immune system known in the West as the Great Firewall, Chinese internet users have injected memes with the genetic code of revolutionary dissent.

Though clever, the term “Great Firewall” is reductive nomenclature for China’s next-generation model of repression. The Chinese government’s mechanisms of online censorship are only a fragment of the full picture, and focusing on them presents a misleading image of totalitarian shadow agencies with full control over the media. Chinese companies like Baidu (Google-like search engine), TenCent (instant messenger service), Sina Weibo (Twitter-like microblogging platform), Renren (Facebook-like social networking platform), and Youku and Toudu (YouTube-like video sites) and their competitors not only provide a web-based social forum that could unite in mass protest, but also serve as contractors for government censorship, voluntarily deploying both word filters and teams of staff to expunge dissident speech from their servers. They consider these investments well worth the market share of China’s 400 million (and counting) internet users.

More significant than an official directive, online companies face a profit motive to censor customers’ content. Similarly, it appears that internet users are more urgently motivated by their desire for immediate expression than their abstract yearning for political freedom and openness. As long as internet users can find a way to get through official and corporate firewalls, they may continue to opt for quiet resistance over revolution—which is by no means a failure for progress. The Charter 08 manifesto signed by Nobel Peace Prize winner Liu Xiaobo could be more easily chased from the web than the infectious jokes, games, and code words that circulate as memes through forums, chat rooms, and microblogs.

Western observers frequently imagine that any counter-censorship activity is necessarily insurgent. But in response to such thinking, such as a 2009 New York Times piece on the Grass mud horse phenomenon, many Chinese commenters have asserted that the meme is more joke than protest. In English, Cǎo Ní Mǎ is literally a nonsense phrase, “grass mud horse,” but the homonym cào nǐ mā (with different tones) translates to “Fuck your mother.” While Chinese private and public censors block obscene speech, arguing that pornography cohabitates with sedition, the phrase “grass mud horse” allowed netizens to curse with impunity.

Over time, the grass mud horse began to take on a new life beyond its function as a clever euphemism. A mythic creature depicted initially as a zebra, and then, more famously, as an alpaca, began to roam the web. In a host article posted on Wikipedia-analog Baidu Baike, several word games were strung together to describe a fantasy of liberation that was initially invisible to censors. It elaborated that the creature lives in a desert called Ma Le Ge Bi (which resembles another insult) and eats Wo Cao (literally “fertile grass,” but naturally resembling yet another profane outburst).

Most saliently, the Cao Ni Ma was given a nemesis, the héxiè, which literally means “river crab” but which was already established as a code word designed to elude censorship and police intervention. The near-homophonous word héxié, literally meaning “harmony,” was a loaded reference to the “Harmonious Society” doctrine of current president Hu Jintao, whose ostensible goal of fostering national unity serves as the mandate for the Chinese government’s aggressive censorship policies. When netizens say that a user has been “harmonized,” the suggestion is that he or she has somehow been brought into compliance by government agents, whether by physical force or by blocking access to his or her account. The code word is a prudent adaptation, since no word is more suspect in a harmonious society than “censorship.”

The grass mud horse, both crude joke and poetic symbol of free speech, and the river crab, a symbol of censorship, allowed netizens to dramatize the conflict with censors without getting themselves “harmonized.” Most importantly, the modern myth of the grass mud horse’s victory over the river crab was infectiously funny, allowing it to spread across the internet in shifting forms. For example, an online music video has a children’s choir singing of the grass mud horse’s exploits, as though to highlight the cuddly creature’s unambiguous decency. Nature mockumentaries described the creature in its natural habitat. Finally, netizens began going out into the real world to visit alpacas at the zoo, posing with the grass mud horses and displaying the pictures on their blogs like a badge of honor.

Even well-established figures in the country’s human rights movement have adopted internet memes as symbols for their struggle. Chinese artist Ai Weiwei has always held an ambiguous position between cooperation with the government and dissent. He served as an artistic consultant on the Beijing Olympics’ bird nest stadium, but he also undertook a number of art projects and documentaries critical of the government’s human rights abuses, recently motivating the police to tear down his Shanghai studio. In tribute to the grass mud horse, Ai posted photos of himself on his website frolicking in the nude with a plush alpaca doll “harmonizing” his privates. The image both celebrates the grass mud horse’s symbolic status as a champion of natural human freedom and evokes the constraints of censorship, as the artist protects himself from full exposure by using the grass mud horse as both a black bar and a perversely exaggerated phallus. Much like the phrase “grass mud horse,” Ai’s alpaca doll announces what it obscures by replacing the unmentionable with a hysterical, unavoidable substitute.

In November 2010, Ai planned to host a banquet at which guests would feast on river crab in order to protest the announcement that his Shanghai studio would be demolished, possibly in retribution for his recent politically sensitive work. As the grass mud horse meme had done when it encouraged bloggers to publicly pose with a “censored” zoo animal, the river crab meme finally made the evolutionary leap from online avatar to real-world political banner. By this point, the river crab had become well known, and the Shanghai authorities contemplated shutting down the banquet. They ultimately settled on placing Ai under house arrest, so that he could not attend his own banquet. Like Liu Xiaobo at the Nobel ceremony, he was reserved a conspicuous seat in absentia.

The river crab and grass mud horse are now well-known political banners that attract government scrutiny. Allegedly, China chose to block domestic servers from YouTube in March 2009, in part to keep citizens from accessing popular grass mud horse videos. But part of what makes memes such an effective carrier of social malaise is precisely their ability to transform in order to hide themselves from the Chinese net’s complex and ever-evolving immune system. As censors catch on to these tools of linguistic evasion, substitutes quickly evolve to take their place—for instance, shuǐchǎn, or “aquatic product,” sometimes takes the place of “river crab” as an allusion to censorship, sidestepping previous techniques of homonym-based linguistic evasion in favor of a different device, synonym.

In order to continue beneath the authorities’ dragnet, subversive memes need to change unpredictably. Netizens frequently alter the logic of their codes, deploying not only homonyms and synonyms to circumvent taboo subjects, but also a technique uniquely possible with Chinese logograms that lies somewhere in between cockney rhyming slang and avant-garde visual poetry. China’s censorship-breakers have created neologisms like 目田, whose individual characters mean “eye” and “field,” by “beheading” the upper strokes of the outlawed words they stand in for. For instance, 目田 (or “eye field”) is formed by slicing the top off the word for freedom, 自由. Not only does the phrase permit the writer to articulate an expressed idea without attracting attention, but the neologism packs heavy symbolism for those who recognize the headless characters as victims of oppression—the censors have decapitated freedom in the pursuit of national harmony.

Crucial to their transmission is the pithy symbolism and dark humor contained in such code words. The memes mask progressive, if not necessarily revolutionary, power in their playful character, so that even many of their users appear to see them as functional tools, rather than compact protests. The world-recognized Charter 08 manifesto, a calculated and sustained call for human rights in China, does not take a digital approach to revolutionary politics, even though it was bravely transmitted in semi-public online media channels. Online jokers, whose protests require only a quick wit and a few keystrokes, may prove to have greater stamina, as they are constantly growing, and their tactics are ambiguous and evasive. To the world, Liu Xiaobo has become a symbol of both the revolutionary spirit and of the Chinese government’s oppressive force. Though they have remained relatively unheralded, outlaw memes are a daily act of protest that go largely unpunished.

One internet meme that was developed to honor Liu behind the Great Firewall again plays with linguistic ambiguity, taking advantage of his common family name. Users on Twitter and other microblogging sites have paid tribute to Liu with posts that lead readers down the garden path to subversive thinking by describing a historically venerated individual with the last name Liu. These traditionally respected figures all have noncontroversial attributes in common with Liu Xiaobo, but only at the last minute does the blog writer reveal the “true” object of his or her appreciation. For instance, this post by wentommy pays homage to Liu Xuande (or Liu Bei), hero of the 14th-century epic Romance of the Three Kingdoms:

The person I most admire has the surname Liu. He enjoys immense prestige among the common people, but is a thorn in the side of the powerful. He is known for his humanity and kindness, and even when insulted he endures it with tolerance. In times of distress he would give up his family before his morals, and faces danger willingly. But some have criticized him for fake humanity and false righteousness. His name is Liu....XuandeThese posts not only allow their writers to discretely honor a state criminal, but also show that Liu Xiaobo’s character reaches across time to unite him with Chinese tradition, despite his status as a political prisoner. The posts suggest the universal humanity of resistance, and they honor Liu’s timeless bravery and moral strength, rather than his specific actions. The meme appeals to the common character of individuals who stand up against moral wrongs to knock down the walls that keep dissenting voices behind bars and the virtual walls that exclude critical speech. The Great Firewall’s virtual and human filters have made it impossible to honor a single man, but have inspired internet users to recognize commonality in his actions. Even the human censors might be moved to consider whether these posts are attacks on authority or innocent paeans to the national character.

In the history of resistance to authoritarian power, China’s online campaign for free speech is remarkable in that it takes advantage of unique possibilities of the Chinese language, as well as the technological possibilities of the internet. Unlike the extended metaphors of print-bound insurgencies, Chinese internet resistance aims for the kind of instant poignancy that generates further memes and leads to mass micro-movements. The online medium’s challenges and opportunities inspire subversive memes. Operating in a semi-public space, online rallying cries can be heard by a wider audience than samizdats, crude graffiti, and furtive whispers, but they can also be efficiently tracked and dismantled. But by inciting outrage with a few characters, memes can pass by censors and turn jokes and profanities into unified protest.