Etha Williams

Setting Words to Music: Rameau’s Nephew and the Way the Enlightenment Listened

ISSUE 9 | RECONSTRUCTION | OCT 2011

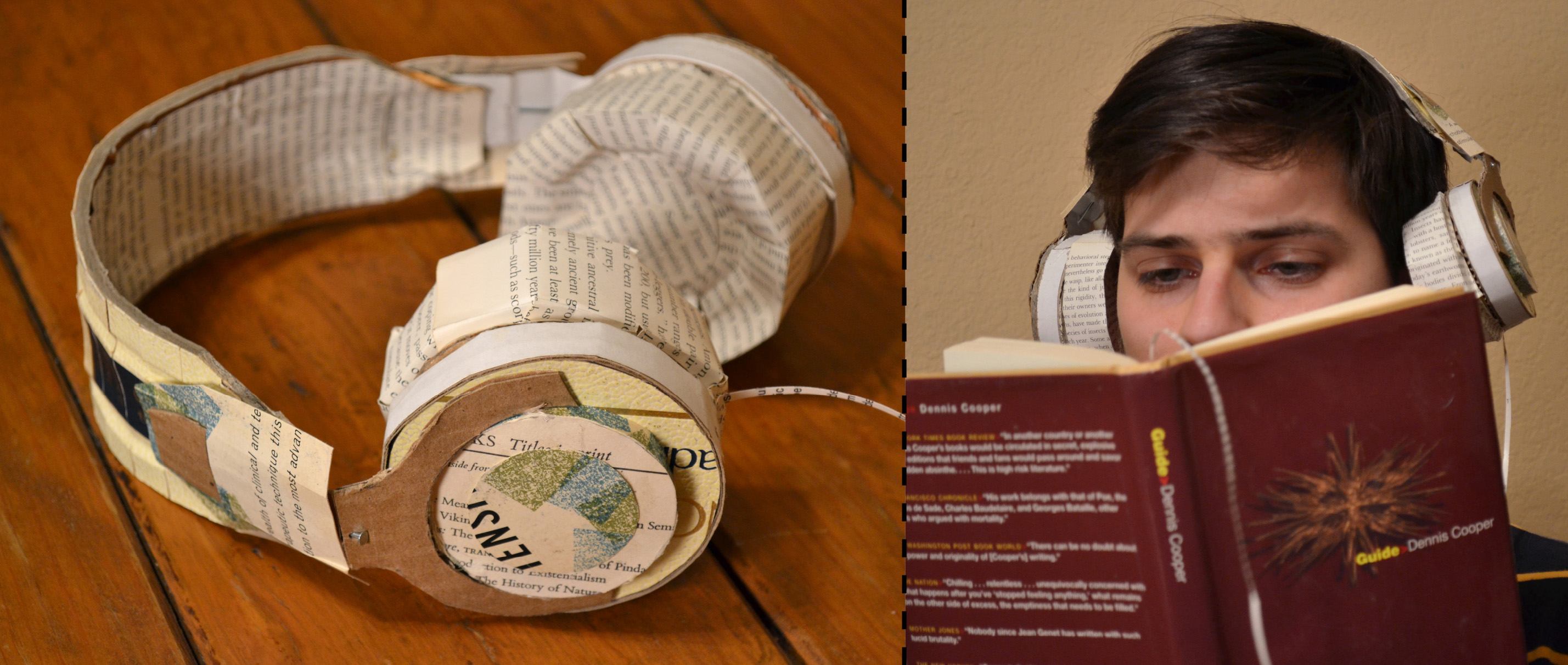

Sculpture and image by Zachary Nash

“I felt before I thought: this is the common lot of humanity.” —Jean-Jacques Rousseau

Despite the perceived difficulty of talking about musical phenomena—the popular comparison with “dancing about architecture” springs to mind—professional musicians and amateur listeners alike have attempted to do so for centuries. This may serve a variety of purposes, including criticism (for instance, a columnist assessing a work), analysis (a musicologist explaining an aspect of a work), exposition (describing a work to someone who has not heard it), or sympathetic remembrance (recalling a work with someone else who has heard it); in all of these situations, the way in which the speaker or author translates musical phenomena into words reveals important elements of how he understands the phenomena themselves. In Diderot's Rameau's Nephew, all four of these strains combine to give the reader a vivid, sometimes contradictory portrayal of the changes French musical perception was undergoing during the late 18th century.

Throughout history, modes of understanding musical phenomena, and thus of verbally representing and reconstructing them, have undergone significant changes; in his fascinating study Listening in Paris, James Johnson details a shift in French listeners' musical understanding from a Baroque/classical perception of music oriented towards outwardly focused, melodically-mediated signification to a Romantic/modern one oriented towards inwardly focused, harmonically-mediated sensation. Throughout much of the 18th century, discourse on music centered around and emphasized music as imitation, achieved primarily through melody, of extra-musical phenomena external to the subject, but as the century came to a close and Romanticism began to take hold, harmony superseded melody in perceived importance, and the terms of the discussion became less definite, more personal, and more ensconced in either specifically musical jargon on the one hand or approximate metaphor on the other. In 1761, the Manuel de l’Homme du Monde could still confidently claim, “All music must have a signification and a meaning, the same as poetry; thus the sounds must conform to the things they express”; but by 1796, Jean-Baptiste Leclerc, a French revolutionary instrumental in creating the Conservatoire de Musique, despaired of such unequivocal signification: “Ask ten people the meaning of a Haydn symphony and you'll get ten different replies—I've tried this experiment myself.”

This understanding of the roles of melody and harmony was clearly a social construction: there is nothing inherent in melody implying that it should be heard as imitation, nor anything inherent in harmony suggesting that it should not be (and indeed, in different times and cultures both have been perceived differently). But for Parisian listeners of the late eighteenth century, the orientation toward melody as imitation was a powerful interpretive framework, supported through analogies with language and, somewhat more obliquely, with painting. Thus could Rousseau claim with many listeners of his time, “At first, there was no music but melody and no other melody than the varied sounds of speech... A tongue which has only articulations and words has only half its riches. True, it expresses ideas; but for the expression of feelings and images it still needs rhythm and sounds, which is to say melody….”; and, “The role of melody in music is precisely that of drawing in a painting. This is what constitutes the strokes and figures, of which harmony and sounds are merely the colors. But, it is said, melody is merely a succession of sounds. No doubt. And drawing is only an arrangement of colors.”

The music itself made use of a variety of techniques to achieve this imitative end. Numerous composers in numerous different works decorated the same key words—words like “ondes,” “vole,” and “enchaine” (“waves,” “fly,” and “enchain”)—with vocal melismata; at other times, composers used orchestral effects to enhance the melody's imitative potential. The range of possible imitation was quite wide; it included natural phenomena such as storms and birdsong and expressions of human sentiment alike. It is tempting to see the imitation of human sentiment in modern terms, as the depiction of a unique and diffuse subjective state, but such an interpretation would be anachronistic: in their 18th-century musical manifestations, such feelings were turned outward and held to be repeatably representable, and thus substantially closer to the imitation of waves and birdsong than to the subjective evocation of psychological feeling with which the Romantic sensibility is familiar.

One can get a good idea of what constituted imitation for the 18th century listener from the following excerpts:

Example 1:

-The use of instrumental effects to imitate a storm made this a big hit with Parisian audiences; its spirit of imitation speaks for itself.

Example 2:

-Text: “Vole enchaine un peuple rebelle/Par les mains de la Volupté/Partout où regne la beauté/ L'amour triomphe avec elle.” (“Fly, enchain a rebellious people/by the hands of pleasure/Everywhere that beauty reigns/Love will triumph with her.) The melisma on “vole” and “enchaine”—both words which were frequently decorated thus—suggest the actions of flight and enchainment, respectively. While such effects may seem strange to contemporary listeners, listeners of the 18th century were intimately familiar with them and interpreted them accordingly. More generally, the melody as a whole gives an admirable portrayal of voluptuousness.

Example 3:

Note the declamatory style throughout, the degree to which the singing imitates speech. The correspondence of the declamatory melody to the feelings expressed is especially clear at such heightened moments as 2:22—“Persée! Arrétez, arrétez!” (“Perseus! Stop, stop!” )—and 2:40—“Par l'excès de mes douleurs/Connoissez, s'il se peut, l'excès de ma tendresse” (“In the excess of my sorrows, recognize, if you can, the excess of my tenderness” ). Indeed, Lully's listeners would have recognized this sorrow and tenderness as much in the music they heard as in the acting they saw.

During the latter half of the 18th century, however, a nascent new paradigm was beginning to encroach on the familiar, imitative mode of listening; indeed, this threat may partially account for the abundant musical discourse defending the latter. It was centered on two phenomena: socially, the valorization of sensibilité, which made its mark on musical life in the weeping and outright hysteria that audiences frequently exhibited at the Opéra; and musically, a gradual shift towards greater harmonic complexity in the music performed. Jean-Philippe Rameau (1683-1764) was one of the earliest exponents of greater harmonic complexity in French opera. His works made use of increasingly sophisticated harmonic materials compared to those of his predecessors, and in his theoretical writing Rameau even went so far as to say that melody was in fact derived from harmony (in contrast to the dominant view of the primacy of melody) and that the latter could excite emotions in the sensitive listener. This was not initially well-received by the wider public, who accused his music of being recherché and overcomplicated; one critic summed up these charges in a rhyme:

To judge our modern music

I have a simple plan:

If beauty is a theorem

Rameau's a brilliant man.

But if by chance, pure nature

Guides beauty as its rule,

Then art must strive to paint it,

And Rameau's an utter fool.

What success Rameau's music did enjoy was primarily due to his continued use of imitative melody alongside the newly complex harmony (consider Example 2 above). However, other composers, such as Gluck, whose music awakened Parisian sensibility to an unparalleled degree, were appreciated as much for the pathos that listeners identified in their harmonies as for the imitative power of their melodies. It is hard to say exactly how this transformation took place; perhaps the best explanation is that harmony, at the time a hermeneutically empty vessel, was in a prime position to be filled with the sensibilité that Parisian audiences already felt in excess.

Diderot's unpublished satire Rameau's Nephew (c. 1761-1772), written at the twilight of the era in which music was perceived as imitation, speaks vividly to these changes in musical understanding and perception. It constructs a philosophical dialog between the narrator, known simply as “Moi,” and the nephew—“Lui”—of Rameau. Rameau, we will recall, was at the forefront of harmonic innovation, a position which earned him no small measure of scorn and mistrust from both the musical public and philosophers and critics of the day. His harmonies, listeners claimed, were unnatural and overdone; his accompaniments were “racked, flayed, and dislocated” so as to be nearly unbearable. In the Querelle des Bouffons, a rivalry between 18th-century French and Italian opera composers, those who sided with the Italians often claimed that Italian music preserved music in its natural, melodically-oriented state and accused Rameau of having decisively ruined French opera with his unnatural harmonies.

This debate over Rameau's music ultimately led to a quarrel between Rameau and Rousseau. The issues at stake included no small measure of personal pride—Rousseau, a would-be composer himself, felt slighted by Rameau's lack of appreciation for his efforts, and would later claim that Rameau had stolen and taken credit for his work—but differences in musical belief played a prominent part as well. While Rameau maintained that harmony possessed an expressive importance equal to, if not greater than, that of melody, Rousseau, on the other hand, continued to uphold the primacy of imitative melody and took the side of the Italian composers in the Querelle des Bouffons. It is in this charged context that Diderot wrote Rameau's Nephew.

In the dialog, Lui—based partially but not entirely on Rameau's actual nephew, Jean-François Rameau, who was also a composer and musician—is presented as a slighted relation of the famed composer, living hand-to-mouth off rich men whom he flatters or cheats as necessary. Lui's contradictory character pervades the dialogue; as Moi describes him at the opening, “He is a mixture of loftiness and depravity, of good sense and buffoonery. The notions of honesty and dishonesty must be really badly confused in his head, for he shows without ostentation that nature has given him fine qualities, and has no shame in revealing that he has also received some bad ones.” This character is able to reveal opinions and truths that, to Moi's mind, are repugnant or scandalous; Moi frequently censures them, yet at the same time recognizes them as compelling. The rational intellect embodied in Moi is confronted with the sensual appetite embodied in Lui—and neither emerges decisively victorious.

Music is a theme throughout the dialog, but its most lengthy exposition comes towards the end of the work, just after Lui has scandalized Moi with a tale of consummate and vicious hypocrisy. Wishing to change the subject, Moi turns back to music and asks Lui about the definition and basis of melody. The discussion begins rationally and conventionally enough; Lui responds:

“A melody is an imitation using the sounds of a scale invented by art or inspired by nature, whichever you like, either with the voice or with an instrument, an imitation of the physical sounds or accents of passion. You see that, by changing some things in this definition, it would fit exactly a definition of painting, oratory, sculpture, and poetry. Now, to get to your question. What's the musician's model or the model of a melody? It's declamation, if the model is alive and thinking; it's noise, if the model is inanimate. …

“When one hears Je suis un pauvre diable, one thinks one can recognize the sad cry of a miser. If he wasn't singing, he would speak to the earth in the same tones when he entrusts his gold to it, saying, O terre, reçois mon trésor. And that little girl who feels her heart beating, who blushes, who's confused, and who begs the gentleman to let her go—would she express herself any differently? In these works there are all sorts of characters, an infinite variety of declamations. That's sublime—I'm the one telling you this. Go on, go on and listen to the piece where the young man who feels himself dying, cries out, Mon coeur s'en va. Listen to the song. Listen to the instrumental accompaniment, and then tell me what difference there is between the real actions of a man who's dying and the form of the melody.”

In itself, this line of argument is hardly exceptional; it echoes what numerous theorists, philosophers, and listeners of the time were saying. Music is an imitative art little different from painting or other art forms; its medium may be different, but its ends are the same. In discussing the imitation of physical sounds, Lui references the numerous and often hugely popular musical depictions of such phenomena as storms, waves and birdsong. His claim that, for human passions, declamation is the model makes clear reference to Rousseau's application of his theory of language to music: in his On the Origin of Language, Rousseau asserts that language has its origin in expressions of passion, and that this origin is preserved in musical expression. The musical excerpts Lui cites to support his claims are all from operas by Duni1 , a well-received composer of the time whose music combined elements of French and Italian opera in music that was very declamatory indeed and that eschewed much of Rameau's harmonic complexity.

But then, after the two men have discussed the relative merits of various contemporary musicians, the tenor of the conversation suddenly changes. Moi politely responds, “There's some reason in everything you've just said,” a claim against which Lui reacts violently. He abjures reason and embarks on a chaotic performance of a medley of the music in question. The episode is worth quoting at length:

“He began to get worked up and to sing very softly. As he grew even more impassioned, he raised his voice, and then there followed gestures, facial grimaces, and bodily contortions. I say, 'All right, there he is off his head, getting some new scene ready.' Then, in fact, he set off with a loud shout, 'Je suis un pauvre misérable... Monseigneur, Monseigneur, laissez-moi partir . . . O terre, reçois mon or; conserve bien mon trésor . . . Mon âme, mon âme, ma vie, O terre! . . . Le voilà le petit ami, le voilà le petit ami! Aspettare e non venire...A Zerbina penserete...Sempre in contrasti con te si sta...' He crammed together and jumbled up together thirty songs—Italian, French, tragic, comic—in all sorts of different styles. Sometimes in a bass voice he went down all the way to hell, and sometimes he'd feign a falsetto and sing at the top of his voice, tearing into the high points of some songs, imitating the walk, deportment, gestures of the different singing characters, by turns furious, soft, imperious, sniggering. At one point, he's a young girl crying—portraying all her mannerisms—at another point he's a priest, he's a king, he's a tyrant—he threatens, commands, loses his temper. He's a slave. He obeys. He calms down, he laments, he complains, he laughs—never straying from the tone, rhythm, or sense of the words or the character of the song.

“… As he was singing snatches from 'Lamentations' by Jommelli, he brought out the most beautiful parts of each piece with precision, truth, and an incredible warmth. That beautiful recitative in which the prophet describes the desolation of Jerusalem he bathed in a flood of tears which brought tears to everyone's eyes. Everything was there—the delicacy of the song, the force of expression, the sorrow. He stressed those places where the composer had particularly demonstrated his great mastery. If he stopped the singing part, it was to take up the part of the instruments, which he left suddenly to return to the vocals, moving from one to the other in such a way as to maintain the connections and the overall unity, taking hold of our souls and keeping them suspended in the most unusual situation which I've ever experienced. Did I admire him? Oh yes, I admired him! Was I touched with pity? I was touched with pity. But a tinge of ridicule was mixed in with these feelings and spoiled them.

“…What didn't I see him do? He cried, he laughed, he sighed, he looked tender or calm or angry—a woman who was swooning in grief, an unhappy man left in total despair, a temple being built, birds calming down at sunset, waters either murmuring in a cool lonely place or descending in a torrent from the high mountains, a storm, a tempest, the cries of those who are going to die intermingled with the whistling winds, the bursts of thunder, the night, with its shadows—silent and dark—for sounds do depict even silence.”

To appreciate the full force of this passage, one should first of all realize that Diderot's readers would have been intimately familiar with the music in question. They would have read Lui's polystylistic medley much as a contemporary reader might read an account in which someone sang, one after another, snatches of Katy Perry, The Beatles, and Radiohead, all the while acting out the music videos as well. It is a profoundly comical scene, but also one which viscerally evokes the various musical styles of the day. And it is a scene which, though patently ridiculous, is also at times admirable and even moving.

Much of Lui's extraordinary acting out of musical experience echoes and reinforces the arguments regarding imitation that he had made in his previous, more reasoned state; but they are transposed from a register of criticism and analysis to one of experiential exposition. One notes that those passages whose imitative power Lui had previously praised—“Je suis un pauvre diable”; “O terre, reçois mon trésor”; the girl's plea that the gentleman let her go; and “Mon coeur s'en va”—are all included in his opening medley (along with several Italian arias from Pergolesi's “La serva padrona”), although interestingly, while the titles of the first two had been mis-cited in Lui's analysis of melody, they are here more correctly recalled as “Je suis un pauvre misérable” and “O terre, reçois mon or, conserve bien mon trésor” (emphases added), perhaps implying that Lui's impassioned performance is in some ways more true to the music in question than was his reasoned argument.

The breathless narrative conveys viscerally the nephew's succession of imitative incarnations, frequently identifying Lui with the people he is imitating. The 20th-century reader becomes caught up in it through sheer force of style, and one must imagine that for an 18th-century reader who was intimately familiar with the music involved, the effect was all the stronger. While Lui's imitation takes on extra-musical qualities such as gesture and deportment, the transformation itself is made through the medium of music, music which can by turns “cry, laugh, and sigh.” Now, instead of simply being told that the Duni arias perfectly embody the passions they are supposed to capture, the reader, impelled by Diderot's vivid descriptions, reconstructs the music mentally and feels those passions for himself.

For all that this episode seems to support the arguments earlier advanced concerning the 18th-century way of listening, however, it also presents moments of contradiction. These are already suggested in the two Duni arias whose titles are misremembered in Lui's respectable, rational argument but correctly recalled in his somewhat ridiculous, passionate performance: if certain aspects of music are accessible only in the act of creating music and not in the act of discussing it, to what extent can such discussions really be trusted? And why did Lui get the titles wrong at first, but correct himself in singing? This question, at least, has a somewhat straightforward answer: the incorrectly recalled texts have two missing syllables (in the case of “Je suis un pauvre diable”/“Je suis un pauvre misérable”) or an extra syllable (in the case of “O terre, reçois mon trésor/O terre, reçois mon or...”), and this syllabic difference would cause problems in singing the melody. (It is worth noting that the remaining mistake – “reçois” for “voici” – does not interfere in this regard.) It is thus precisely the musical aspect of the texts in question that Lui's first argument gets wrong, and moreover in the very quality (declamation) which his previous argument had made out to be of utmost importance. The incorrect titles do not deviate substantially in meaning from the correct ones, but they do not fit the music.

The tension of Lui's performance with his earlier argument becomes all the greater when he turns to singing Jommelli's “Lamentations,” wringing tears from his listeners. Given the attitudes regarding melody and harmony expressed previously, this choice of repertoire is an unexpected one indeed. Quite unlike Duni's music, Jommelli's is replete with the very qualities that audiences found objectionable in Rameau: complex, chromatic harmony and dense instrumental accompaniment. And yet, it is this very music which most enraptures the crowd. Also, Lui's performance is now described in overtly expressive terms (“bathed in a flood of tears…the force of expression, the sorrow”) rather than imitative terms (“a young girl crying—portraying all her mannerisms”); this, moreover, brings the listeners themselves to tears. Diderot describes the experience as very much internal to the individual listeners' “souls”—in contrast to the doctrine of outwardly oriented imitation—and markedly atypical (“the most unusual situation that I've ever experienced”).

The reaction to this unusual situation, of course, is far from unequivocal; the listener's tears are bracketed by ridiculing laughter. Moreover, in saying that the ridicule “spoiled” his more indulgent feelings, Moi uses the verb “dénaturait,” a highly charged word in a time when “unnatural” was one of the worst charges one could levy against music (and a charge, moreover, frequently brought against harmonically complex music). Nevertheless, tears, pity, and admiration exist alongside ridicule and mistrust at what seems “unnatural,” and in this one sees the conflicted begins of a new form of musical experience, a form perhaps too new, and moreover too internal to the subject, to be expressed in rational argument, but one which nevertheless comes out in the acts of performance and listening themselves.

Following this extraordinary outburst, Lui seems to return to imitation; the remainder of his performance catalogues a truly impressive variety of natural sounds and human passion that gives a vivid picture of the whole gamut of phenomena, natural and sentimental, that 18th-century listeners believed could be imitated. However, even here imitation is not unproblematic; the final phenomenon imitated is silence itself. Diderot's claim that “sounds do depict even silence,” at best, stretches the concept of imitation to its very limits. If, as Lui previously claimed, music is more or less analogous to painting, then claiming that sounds can depict silence is akin to saying that color can depict the invisible. Doing either requires a degree of abstraction, of seeing sounds used in music or colors used in painting as something more than simply sounds and colors, that falls somewhat outside of the bounds of musical sound as imitative of those sounds that humans and nature produce. However far-fetched it might seem to us to think of music imitating “a temple being built” or “an unhappy man left in total despair,” both of these at least phenomena at least make some sort of noise the sound of a chisel against stone, the sound of sighs or groans—whereas in the case of silence, sound is antithetical to the very phenomenon it is supposed to represent.

In considering Lui's two somewhat contradictory presentations of musical phenomena, it is useful to note once more the very different registers in which each is made. Lui's initial argument is made primarily in analytical (when discussing the meaning and basis of melody) and critical (when discussing the merits of various composers and schools) modes. It begins from a standpoint of Enlightenment rationality with an assumed common experience of the music and makes its arguments on this basis. In his subsequent performance, on the other hand, Lui no longer assumes this experiential foundation and instead seeks to reconstruct the experience of listening itself in a way that is chaotic, often irrational, yet ultimately quite compelling. In doing so, he shows the constantly changing social practice of listening to be rather more complex than he might previously have assumed. Melodic imitation, it is true, is crucial to the manic appeal of the performance; but, bleeding outside these lines, expression of sentiment through harmony and the problem of “imitating” that which might seem inimitable are undeniably present as well, and point the way to a different mode of listening that was beginning to emerge at the time.

There is perhaps no more poignant indication of the gulf between the two parts of Lui's discourse, and the change in musical understanding that gulf represents, than the way Lui closes each. After discussing the nature and construction of melody, Lui asserts, “And you should believe everything I've said about this, because it's the truth”; but after his performance: “Well then, gentlemen, what's going on? Why are you laughing? What's so surprising? What's happening? Now that's what people should call music and a musician.” In the first case, Lui appeals to external truth, perceived and judged by means of reason. In the second, however, himself discombobulated and unsure of what's happening, he can merely point to the listeners' shared experience of his performance as a model for what music should be: passionate and expressive of things which, at times, exceed the given boundaries of imitation. In this, he embodies the state of many Parisian listeners towards the end of the 18th century: caught between what they thought music must be and what they felt it was becoming.

1 The first aria is completely faithful to Duni's text. In the second, however, there remains a slight mistake: it should be “O terre, voici mon or...”

The Hypocrite Reader is free, but we publish some of the most fascinating writing on the internet. Our editors are volunteers and, until recently, so were our writers. During the 2020 coronavirus pandemic, we decided we needed to find a way to pay contributors for their work.

Help us pay writers (and our server bills) so we can keep this stuff coming. At that link, you can become a recurring backer on Patreon, where we offer thrilling rewards to our supporters. If you can't swing a monthly donation, you can also make a 1-time donation through our Ko-fi; even a few dollars helps!

The Hypocrite Reader operates without any kind of institutional support, and for the foreseeable future we plan to keep it that way. Your contributions are the only way we are able to keep doing what we do!

And if you'd like to read more of our useful, unexpected content, you can join our mailing list so that you'll hear from us when we publish.