Eric M Gurevitch

Signification and Its Discontents

ISSUE 38 | SCRIPTIO DEFECTIVA | MAR 2014

583. “But you talk as if I weren’t really expecting, hoping, now—as I thought I was. As if what were happening now had no deep significance.”—What does it mean to say “What is happening now has significance” or “has deep significance”? What is a deep feeling? Could someone have a feeling of ardent love or hope for the space of one second—no matter what preceded or followed this second?—What is happening now has significance—in these surroundings. The surroundings give it its importance. And the word “hope” refers to a phenomenon of human life. (A smiling mouth smiles only in a human face.)111. Let us ask ourselves: why do we feel a grammatical joke to be deep?

—Ludwig Wittgenstein, Philosophical Investigations1

I. Tell Me a Story

I will begin this process with you. I will begin it with you because you asked me to—you asked me to speak to you, to write to you. This imperative, to be spoken to, is one often experienced in bed with a lover when all else grows quiet—speak to me—what are you thinking about? As if the gap that now exists between two people can be filled with words. Eliot captures this moment of the question and the somehow refreshingly bitter, sarcastic, and lame response in The Waste Land—

“My nerves are bad to-night. Yes, bad. Stay with me.

“Speak to me. Why do you never speak. Speak.

“What are you thinking of? What thinking? What?

I never know what you are thinking. Think.”

I think we are in rats’ alley

Where the dead men lost their bones.2

By asking (no, demanding!) that I speak to you, that I not stop writing, you make me signify myself. You become my significant other.

But asking for thoughts is not quite enough; they elicit an empty response: I think we are in rats’ alley.

Parvati and Shiva find themselves in their bedroom and Shiva seats Parvati on his lap. Presumably they have gotten tired of sex (often their initial sexual union is presented as lasting dozens of years), and Parvati looks over at her lover and asks him to tell me a story—a new one—that no one has heard before. This is how the massive Sanskrit collection of stories entitled the Kathāsaritsāgara, The Ocean Streams of Story, written by Somadeva, opens before descending into a tangled web of narrative frames, of stories nested within stories.

Parvati and Shiva sitting together atop Mount Kailash as the demon Ravana tries to lift it. From the caves at Ellora. Photograph by Eric M Gurevitch

Shiva is happy to oblige his lover, and he drifts into a story that no one, not even Parvati, has heard before—he tells Parvati the stories of her previous births. First, he tells her of the time he manifested himself as a giant lingam. Brahma and Vishnu wanted to see who could reach its end fastest. Vishnu goes up, Brahma goes down, and eventually Shiva reveals himself and the futility of their effort. You, Shiva says to Parvati, were Vishnu. He then goes on to say that she was his wife Sati in a prior birth. Her father said some inopportune things about Shiva, and Sati proceeded to set herself on fire as Shiva crashed the party and beheaded his father-in-law, the poor Daksha.

Shiva manifesting as a lingam with Vishnu as a boar diving down and Brahma flying up. Great Temple, Thanjavur. Photograph by Emma Stein.

Parvati is unimpressed by these stories. Those were terribly boring! she exclaims, her jealousy that Shiva may have been with another woman (even if that other woman was herself) showing through. Tell me an interesting story!

And so Shiva, still holding Parvati on his lap, proceeds to tell her a story that has nothing to do with her. It is an exciting story, and it is overheard by the guard listening at the door. The guard tells the story to his wife, and, well, you know how a woman with a good story is—soon the whole town knows. Parvati is furious—first at Shiva for telling her a story that even the common villagers know, and then when she finds out what happened, at the servant who was eavesdropping on their conversation. Shiva curses the servant to be reborn as a human until he can properly tell a story, and, well… that’s a story for another time and place.

For now, it is sufficient to note that Shiva was always with Parvati, but Parvati wasn’t always Parvati. Sometimes she was Sati. She wasn’t even always a woman. Sometimes she was Vishnu. What is important is not her sex, not some mystical union of opposite dynamic forces in the universe (although that would become of utmost importance in Tantric circles), but her relationship with Shiva, her challenging, mocking, and loving him. But equally important is that this is unimportant to Parvati, or at least uninteresting. Of course she was with Shiva in previous lives, but she doesn’t want to hear that from him. She doesn’t want to hear him waxing poetic about their time together, she wants to see the world as he renders it.

II. United Words

Kālidāsa, the most famous Sanskrit poet, begins his heroic poem the Raghuvaṁśa with a verse that is still widely recited throughout India. If someone knows even ten Sanskrit verses this is bound to be one of them. I have recited it with strangers in copy-shops and trains to Chennai. It is a pretty verse, replete with alliteration and word play. It goes—

vāgarthāviva saṁpṛktau vāgarthapratipattaye|

jagataḥ pitarau vande pārvatīparameśvarau||

Ragh. 1.1 chanted by Eric M. Gurevitch

Because of the content of the verse, it can be translated into English only somewhat tongue-in-cheekily. It says—

As signifier and signified are entangled

when the meaning of a word is understood,

so too are Parvati and Shiva,

the parents of the world.

I praise them!

It begins with a simile marked by the particle iva. On one side of the comparison are Parvati and Shiva (in that order), the cosmic couple—on the other side are speech and meaning (in that order). Mediating these two is their commonality; they are both saṁpṛktau, joined together, entangled. Just as words without meaning would be useless, so too with Parvati and Shiva. They are a single syntactic unit.

This is a beautiful image on its own, but the words will have even more resonance for the Indian academic versed in philosophy. The 14th-century commentator Mallinātha explains the verse by appealing to what became the orthodox philosophical position of the Mīmāṃsā school—

nityasaṁbaddhāvityarthaḥ| nityasaṁbaddhayorupamānatvenopādānāt 'nityaḥ śabdārthasaṁbandhaḥ' iti mīmāmsakāh| The meaning is that the two are eternally joined together. From the employment of a simile for that which is joined together eternally. As the Mīmāṃsāka says, “there is a joining together of meaning and word eternally.”

In the original verse Kālidāsa makes it clear that word and meaning are joined together for a purpose (provided in the dative case)—so that they can be understood—but in Mallinātha’s commentary, there is a subtle shift away from the use-value of this joining. The emphasis is now on the stability of their union—its eternity. This is backed up by an appeal to a theo-philosophical authority.

The debate over words and signification is probably the philosophical debate par excellence in Indian philosophy and one that goes back at least to Yāska’s Nirukta, a grammatical text that was written before Sanskrit was formalized by Pāṇini. Yāska is primarily writing a reference work for difficult words found in the Vedas, but, along the way, he addresses the basic principles of language. His analysis of how language works is not secondary to his analysis of the difficult words themselves; his main guiding principle is that all nouns are derived from verbal roots. These verbal roots are meaningful containers that can morph into new forms without losing their meaning. Many views would come to attack this position, but it remains the basis for much Indian linguistic theory.3

Critiques of the theory of conjoined signifier-and-signified came from those who accepted the authority of the Vedas, but the most vicious were from those who did not (especially Buddhists of the Yogācāra School). The question of signification becomes a sectarian question. (As happened during the Protestant Reformation, with Heinrich Bullinger and Ulrich Zwingli leading the anti-Mīmāṃsa charge.) All questions of signification have political implications. The Mīmāṃsāka position, which eternally binds word and meaning, establishes itself as the authoritative interpreter of the meaning of words, and the words it interprets are authoritative themselves. By asserting the unification of signifier and signified, those in positions of authority can subtly change the valences of words to protect their interests without opposition from those outside of power. Words are powerful entities on their own, the Vedas are the most powerful words, listen to what I say these words literally mean. So the argument goes. (Of course, those outside of power can attempt to radically reimagine the words that are seen as authoritative—once again, the Protestant emphasis on Sola Scriptura is relevant.) On the other hand, if one holds specific words as eternally meaningful (say, oh, the Vedas), another can attack specific words by attacking all words in general. If all words are meaningless, then your authoritative text looks quite shabby, a Buddhist might declare.

But let us get back to our metaphor, which sticks in one’s head much longer than obtuse reasoning. Parvati and Shiva are joined together in a specific grammatical manner—a dvandva-samāsa. (Michael Coulson, the author of the silliest modern Sanskrit primer, calls these “Co-ordinative compounds.”) They are not (as I initially translated above) “Pārvatī and Shiva,” they are ParvatiShiva (pārvatīparameśvarau), a single word conjugated in the dual. Parvati lacks here case termination, and the entire word takes on the masculine declension, this being the gender of the final component, Shiva. Still, they each retain some individuality—we can clearly make out the single words that are joined together. This individuality fades away when we look to the phrase describing them: “the parents of the world” (jagataḥ pitarau). Once again, there is a dvandva-samāsa describing two entities, but this is a special type called an ekaśeṣa-dvandva-samāsa, a co-ordinative compound in which only one term remains. Literally, the word pitarau would mean “the two fathers,” but, as Pāṇini explains, “father and mother [are reduced to only ‘fathers’]” (1.2.64 & 70). Out of the two, only one entity expresses itself.

This image is depicted throughout Indian mythology and iconography as the ardhanārīśvara, “the god who is half female.” Whether cast in bronze or carved in stone, this is a powerful figure. Shiva’s dreadlocks flow down one side of his head in opposition to Parvati’s delicate curls. Parvati’s (almost always) massive breast awkwardly stands out against Shiva’s flat bare chest. But in their union, aspects of each individual change. Shiva and Parvati have to be the same height: Indian artists aren’t willing to compromise there and render an entirely mismatched deformed entity. Shiva’s features become more feminine, while Parvati’s become more masculine. In their union they communicate with each other, their borders blending.

Headless Ardhanārīśvara sculpture from Khajuraho. Photograph by Eric M Gurevitch.

Even when they are joined, Shiva and Parvati are not complete. Or better—their unification does not remove their longing to be closer to each other even as they desire to be further from each other—they do not completely dissolve into each other. This is illustrated in a beautiful verse at the beginning of the poet Bilhaṇa’s Vikramaṅkadevacarita, written some seven centuries after Kālidāsa.

ekaḥ stanastuṅgataraḥ parasya vārttāmiva praṣtumagānmukhāgram|

yasyāḥ priyārdhasthitimudvahantyāḥ sā pātu vaḥ parvatarājaputrī||

Vikramāṅkadevacaritam 1.4 chanted by Eric M Gurevitch

That daughter of King Parvata,

Who bears the presence of half of her lover,

Whose single perky breast reaches to the tip of her mouth to ask news of the other—

May she bless all of you.

We are given a powerful image of Parvati (the daughter of Parvata, the mountain). She is the main god we are praising. Though she exists as half-herself-half-her-lover, this verse invokes only her, not even naming her lover.

And then that image of her breast, which occupies the full first half of the verse. (Grammatically, these first two pādas can stand on their own—it’s as if Parvati’s breast has agency itself, a stunning example of the Sasnkrit poetic element of utpreksā) Her breast reaches up to her mouth, as if (once again iva) looking for news of the other, parasya. Is her breast looking for the missing female breast or is it looking for Shiva? The text is ambiguous.4 Either the union is oppressive, and Parvati’s breast misses its companion, or the union is comforting, but there is still more unification her breast desires. Either way the breast asks, where has my partner gone? They are close enough to be suffocating, but still no close enough is close enough.

When we come to Bilhaṇa’s description of Shiva’s half, this yearning present in unification becomes obvious.

pārśvasthapṛthvīdhararājakanyā-prakopavisphūrjitakātarasya|

namo 'stu te mātariti praṇāmāḥ śivasya sandhyāviṣayā jayanti||

Vikramāṅkadevacaritam 1.6 chanted by Eric M. Gurevitch

Let there be praise of Shiva’s praises!

They are successfully directed towards Sandhyā, the evening,

Containing the word “mother,”

Because he is afraid of the thunderbolt of anger

Of Parvati, the daughter of the Mountain,

his side.

Bilhaṇa is inviting us to praise Shiva’s carefully selected words. When he is making his evening prayers Shiva is worried about prompting the jealous anger of Parvati, who might view him as praising a femininized and deified version of the evening. (And there is reason for this jealousy!) Even when she is literally joined to his side, Parvati is jealous of Shiva. And Shiva is careful to note this and chooses his words carefully in an attempt to comfort his other half. They are never able to trust each other completely, they are never fully one. And so Shiva makes it clear that he regards the evening as his mother, thus negating the possibility of sexual competition.

III. Divided Words

One generation after Bilhaṇa wrote the Vikramaṅkadevacarita, in the very same Chalukya court, King Someśvara III is said to have written the Mānasollāsa, a massive encyclopedia of courtly life. It details how a king is to live, how he should be served and how he should interact with the people around him—how he is supposed to behave, dress, and play. It is a long and rambling narrative of some 8000 very technical verses, and a translation has never been published. I am currently assisting Dr. M.A. Jayashree in a translation and new critical edition. The work is going slowly.

Despite what the Mīmāṃsākas would have you think, not every word in Sanskrit is expressed perfectly. Or, rather—due to historical circumstances, not every word survives with either its form or meaning intact.

An example of this comes from verse 1177 of the third book of the Mānasollāsa. It is from the chapter on jewelry in the book of joys (bhūṣābhogaḥ). The particular section lays out types of jewelry that are only for women. I will give the surrounding verses so the context is clear:

The cūḍa ornament 1167. The cūḍa decoration is an ornament for the forearms of women. It is made according to the arm’s specific measurements and is made with pearls, rubies, and diamonds.

1168. What is called the “half-cūḍa” is worn by women. They always love it.

The pādacūḍa (foot cūḍa) ornament

1170-1. These should be worn as pairs, one for each leg. They should be made according to the measure of the section of a woman’s legs. It has diamonds like the cūḍa for the hand and is embedded with various gems. It is called a pādacūḍa. They should be made out of shining gold and be made in three sections.

1172. They are made with pins and are attached at their joints. They can be made with four, six, or eight faces.

The kaṭaka foot ornament

1173. It is either splendid with lines of pleasing golden bubbles or it is smooth and beautiful and makes sounds.

1174. Or it is made with various gems. This foot ornament is called the kaṭaka.

The pādapaṭṭa (foot paṭṭa) ornament

These should be worn as pairs, one for each leg, and are made with various strings of pearls. They sound with either three or five chains.

1175. They are joined together with a pin. This is called the pādapaṭṭa.

The pādaghrgharika (foot jingle-jangle) ornament

These have small bells that shine with gold. The separate parts are tied together with a string.

1176. They are called pādaghrgharika and make pleasing sounds.

The rāḍhaka ornament

This one is made in the same way and has various gems.

1177. It does not make a sound and is good to look at. It is called the rāḍhaka.

The anduka ornament

This is long and circular and made like the kaṭaka.5

1178. It is called the anduka and is a foot ornament that is only for women.

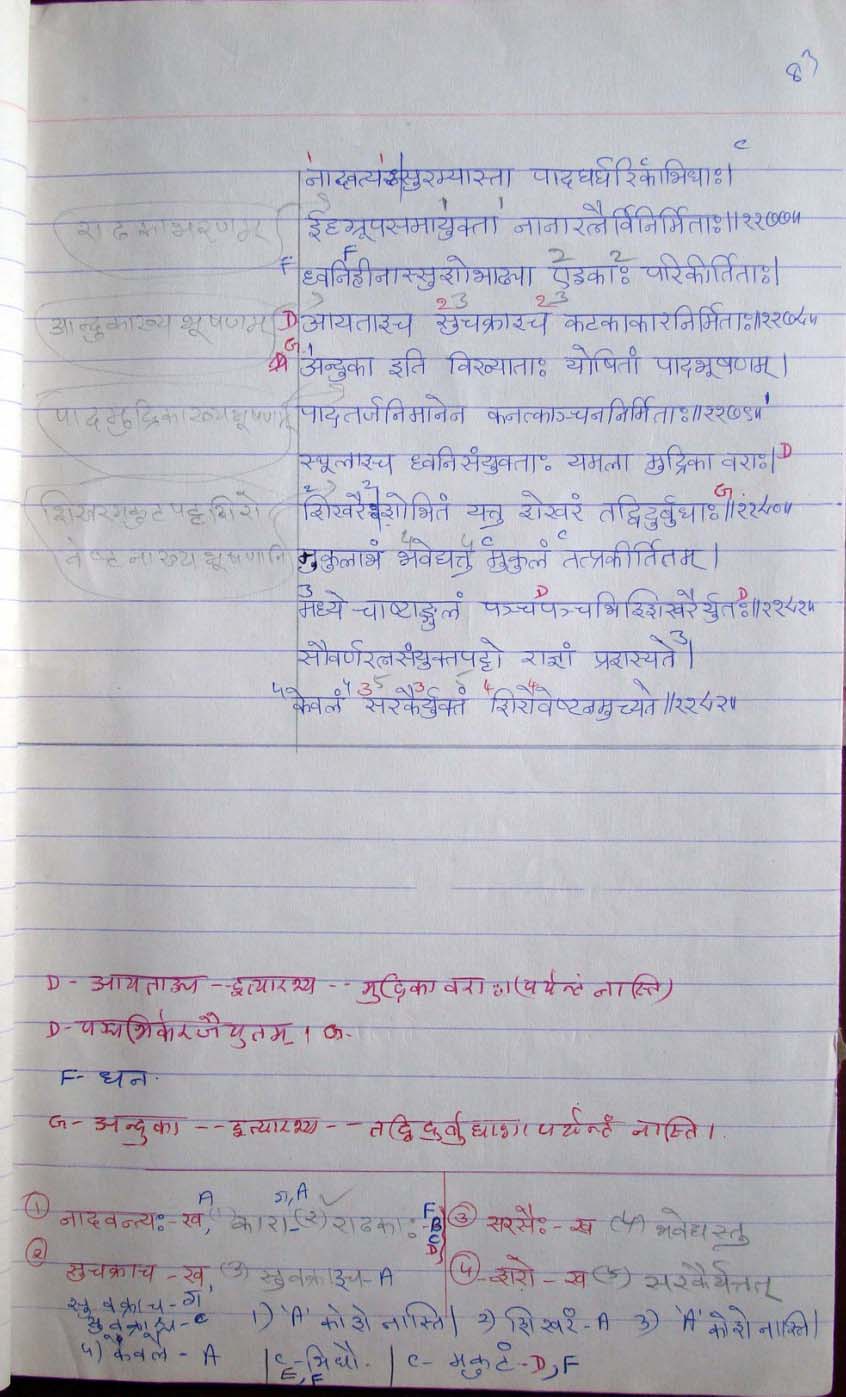

Page from rough draft of Mānasollāsa that deals with the section in question .

King Someśvara III is engaged in the act of naming and standardizing the styles of his kingdom. He doesn’t give us enough information about these ornaments for a reader to be able to construct them on her own. He isn’t inventing new ornaments. Rather, he is giving official recognition to various forms of jewelry that already exist. He is dividing and sorting his nightstand. He is applying a standard name and placing it next to other standard names, placing it next to other things that could be named. The act of naming allows for an object to enter the realm of knowledge. It provides limits for the object, but also new possibilities. It allows for the ornament to become replicated, discussed, worn. It allows for it to become an object of envy—I want a rāḍhaka just like that one! An object of purchase—I’ll take three rāḍhakas! An object of compliment—You look stunning with your rāḍhaka! And an object of prohibition—No one may enter the court without a rāḍhaka!

As time wore on some of the ornaments that Someśvara writes about continued to exist, while others faded away. Styles change, and, as styles go out of fashion, names become forgotten. We see an example of this with the rāḍhaka ornament. Only it may not be a rāḍhaka, it may actually be an eḍākāḥ.

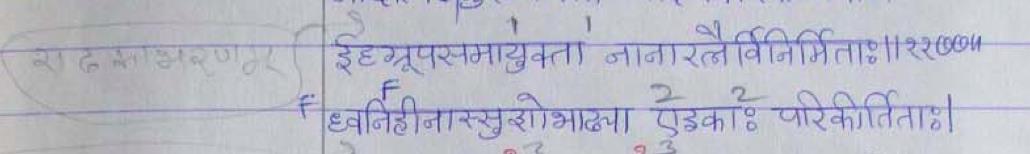

Verse from the Mānasollāsa in question.

Variant readings of verse from the Mānasollāsa.

The issue is one of script. The Devanagari script is used to transcribe most modern Sanskrit texts. While it was always quite popular, this is a hegemony that came along with the printing presses of the British in North India. (It is a North Indian script also used to transcribe Hindi and Marathi.) The confusion in this section of the Mānasollāsa is a confusion that arose rather recently, when mostly South Indian manuscripts were transmitted to a wider Sanskritic intellectual community mediated by European technology. In the Devanagari script, the syllables “rā” and “e” can look very similar, especially if someone is writing quickly or carelessly.

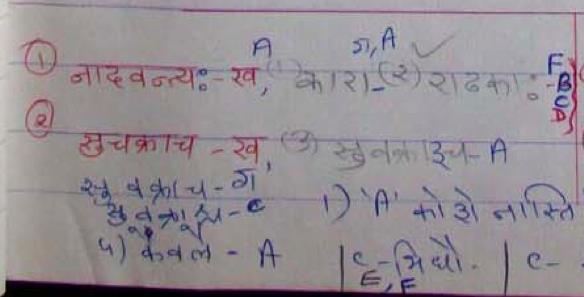

Similarity between “rā” and “e” in the devanagari writing system.

Logically, this was the first change to happen, but it wasn’t the last. Assuming that rāḍhākāḥ is the correct reading (and this is a good assumption to make, since four manuscripts not in devanagari reflect it), the word morphed into eḍhākāḥ at the hands of a wanton scribe. But the change didn’t stop there—eḍhākāḥ is a meaningless word, so it was once again changed, this time to eḍakāḥ. One word uses the aspirated (mahāprāṇa) retroflex “D,” while the other uses the unaspirated (alpaprāṇa) retroflex “D.” One has a long “ā” while the other has a short “a.” (These processes may have occurred concurrently; I do not want to imply the two steps occurred separately, but that is still a possibility.)

Thought went into giving this scribal error meaning. Someone tried to make sense of the mess—someone who had a grasp of Sanskrit but didn’t understand the intricacies of twelfth-century jewelry. One cannot help but try and add meaning to jumbles of letters that have been handed down through history. Rāḍhāka means “a beautiful thing,” while eḍaka means “a sheep.”

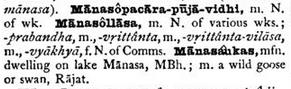

Referring to other reference works doesn’t help us out; this is the work that names. The dictionary itself is corrupt. What was supposed to give names has failed us. The standard Sanskrit dictionary gives only vague reference to the Mānasollāsa itself—there is no mention of most of the objects described in it.

Vague reference to the Mānasollāsa in the Monier-Williams Sanskrit-English dictionary, plagiarized from the German Bohtlingk-Roth Sanskrit Dictionary.

This is an overwhelmingly trite example. The ornament described has almost no unique value—it is almost identical to the other ornaments described around it. It is an ornament that is no longer used. Its name doesn’t describe its function at all. Neither name changes our perception of the object. It is a part of a coded system that has collapsed along with the royal courts that created it.

And yet, it is informative. The separation of word and meaning causes me to stop and think, to search for word and meaning. It makes the words in question and the ornament they once signified conspicuous, rendering them visible, like the glasses I wear but don’t notice until they break or accumulate dust particles or fog up.6 It creates pause. It makes me search. It makes me go back over my notes and try and imagine what this rāḍhāka/eḍaka may have looked like. Is there anything ovine about it? Were women seen as sheep, who needed ornaments to mark and keep track of them? Or is this ornament more beautiful than the other ornaments described? Why might this one have gone out of fashion? And that eternal pesadich question—Why is this other different from all other others?

IV. Significant Others

Modern English is full of passive declarations, double negations, and perhaps worst of all, empty metaphors. Or so George Orwell declares in his famous essay “Politics and the English Language,” as he decries the state of language as he sees it used in academia, press releases, and everyday life. He rails against “using stale metaphors, similes, and idioms, [which] save much mental effort, at the cost of leaving your meaning vague, not only for your reader but for yourself.” Orwell argues that the use of clichés that have been stripped of their (original, intended, referential) meaning strips thought of content and eventually leads to meaningless (and dangerous) politics. The long course of history has severed the connection between the two sides of a metaphor, which leaves us unsure of what exactly we are saying and hence open to simplification and manipulation. His alternative is to have us do two things: 1. We should use simple, direct language 2. When we do use metaphors, we should create new, innovative ones.

The difficulty with new metaphors is twofold—they are difficult to create and they can be difficult to understand.7 We live in a world partially determined by shared clichés, and anything outside of that world often seems outlandish or haphazard. Not that we shouldn’t try. But there is a reason why Kālidāsa, Bilhaṇa, and Somadeva all refer to a similar and familiar image of Shiva and Parvati to start their works. It’s an image any literate Indian would have been able to draw on immediately. And yet, while each poet starts with a common image, each then subtly presents it in a new light, starting with what is familiar and bringing us to a new understanding. We do not always need to start from scratch (whatever that cliché means)—we can look at the metaphors we have, use them to focus our thoughts, and then infiltrate our idiom through them, in turn inverting them or doing away with them altogether.

While these poets present Shiva and Parvati as joined together in a unique manner, it is important that none of them presents them as joined together as a true singularity. Even when they are perfect halves of each other, even when they are both word and meaning, a syntactic unit, they still perform different functions. They still interact and communicate with each other in a confrontational way. These are not Aristophanes’ androgynies from Plato’s Symposium.8

The androgynies, an image used to comment on our current condition in the world, were born as a unity. Each was one person with two heads and eight limbs. And, without a care in the world, they rolled around (which quite naturally is the fastest and easiest (and most pleasurable?) way to get places), eventually attempting to roll up to heaven, which threatened the gods. The gods first thought of killing them as they killed the Titans. But they realize that they would miss these people, who worshipped them and brought them sacrifices. (Gods are so often unwilling to work for their sustenance.)9 And so Zeus came up with an ingenious scheme:

I have a plan which will humble their pride and improve their manners; people shall continue to exist, but I will cut them in two and then they will be diminished in strength and increased in numbers; this will have the advantage of making them more profitable to us.

Ever the good union-buster, Zeus cuts people in two, negating them as a threat and doubling his profit. And so people go on in the world today, looking for their separated half, trying to become a whole, to regain union, as they ignore (or forget about) the real reason for their misery—the fear and greed of the gods. Just as the view of word as unified with meaning supports the hegemonic authority of Mīmāṃsā Vedic orthodoxy, the view of two people as equal halves supports the Olympian gods (and in turn the people and social system the gods support). This state of affairs is one that is held together by a threat of further violence. We should not act against the gods, as Aristophanes ends his speech by saying:

And if we are not obedient to the gods, there is a danger that we shall be split up again and go about like bas-reliefs, like the profile figures having only half a nose which are sculptured on monuments, and that we shall be like symbola.10 Wherefore let us exhort all men to piety, that we may avoid evil, and obtain the good, of which Love is to us the lord and minister; and let no one oppose him—he is the enemy of the gods who oppose him.

This is a dark view of love, one that is enforced through coercion, in which lonely individuals roam the world seeking their other half, accepting the social institutions around them in their loneliness. Yet it remains a dominant metaphor in modern speech. One of our modern clichés that draw so on the image of divided lovers is significant other.

On the surface level, the phrase designates someone important in the speaker’s life. My significant other is most commonly used to describe someone who is important, that there is someone out there who is significant to me, who is my other. My other half. One might say they complete me, they make me whole.

Or that’s what it conveys explicitly. But it also conceals intimacy and shields the one who hears it from the emotional states of the people involved. It is almost never used in the presence of the significant other. It is not a direct form of address, but rather a way of naming in absence. The cliché is used somewhat euphemistically. It masks over certainty, commitment, social institutions, and renders edges blurry. Implicitly, there can be a whole range of meanings—we are unwilling to fully commit to each other, or we are gay and don’t fit into your terms, or you would say we are straight, but we don’t fit into your terms or even I am unsure of what my relationship with this person is, but somehow it is important to me. The person who is addressed as such is often an afterthought. Bring your significant other to our party renders the other insignificant—it can be anyone as long as they are attached (somehow, it doesn’t really matter) to the person addressed. Above all, it is a politeness, someone saying, we won’t exactly define what is occurring. As such, it causes pause.

The phrase itself is meant to be flexible. That is exactly why it retains usage—it can mean so much or so little, depending on the person speaking it and the person listening. What is this person trying to tell me? Does my interpretation of the phrase match with the meaning the speaker is trying to convey? Do we live in the same world of thoughts? This level of reflection is valuable and means that we should not abandon the euphemistic cliché; it already has a resonance with people that should be utilized. But we should try and reimagine it on new grounds that make it more useful. Right now, it conveys meaning through its meaninglessness. By rendering it meaningful once again, we can slip new ideas into old thoughts through our shared lexicon. (This is reminiscent of Trotsky’s appeal to the slogan, but somewhat sexier.)11

The old significant other was a significant other who is comforting. An other who is significant, who was important enough to make me significant, to make me feel important, to give me value when I don’t find value in the world around me. This is the significant other created by the cleaving of the androgynies. They live in a terribly unjust world, a world in which Zeus has divided people in their play. This type of significant other allows people to go on living in an uncomfortable world because they might find their other, who is both a reward and an anesthetic. The other would say something like you mean the world to me. And then go home from his job ordering drone strikes 8,000 miles away and be soothed. They are circles and have created a new world. They look for each other, they search for each other to find their world, to find their meaning, their significance, in the combination, in the unification. This is the other who will hold you and say everything will be alright. Who completes a world, allowing you to forget about the world outside.

Shiva and Parvati show us that Aristophanes’ androgynies aren’t the only necessary spent metaphor with which to imagine human relationships. They remind us that even when we are perfectly close to each other, a yearning, longing, desire, to separate, recombine, be together in different ways continues to exist. And jealousy still exists. The outside world is not forgotten; instead, the outside world is spoken.

The new significant other should be addressed in the second-person, initially leaving out the force of the world, or at least the force of naming for the world. The other will remain an other, will remain outside, desired to be united with. But it is no longer the other who is significant, and it is no longer the other who makes me significant. It is because of the other that I am forced to signify myself. Noun slips into verb and changes in meaning. Because of the other’s appeal to me, to speak, but not about myself, to speak the world, to draw me closer to through my description of the world. We have accepted each other, now let us face this madness. As Parvati demands don’t tell me the story of our relationship, however interesting that might be! Tell me a story of other people and gods! They’re reminded of their separation, but it’s not entirely tragic. It’s precisely that which forces them to signify themselves and brings both closer together.

1 What happens when we imagine Wittgenstein’s interlocutor as his lover? We laugh, which is all in all a good thing.

2 This final line is almost certainly an allusion to the Bṛhadāraṇyaka-Upanishad. Eliot was an amateur Sanskritist and famously ends “The Waste Land” by quoting this text — Datta. Dayadhvam. Damyata. Shantih shantih shantih. In a famous episode in the Bṛhadāraṇyaka-Upanishad, two sages are arguing over how many gods there really are. They argue back and forth and work their way from three thousand and three gods down to just one god (God?) and then back up to three thousand and three once again. At this point, the belligerent and failed scholar’s head explodes. (As is wont to happen if you argue theology poorly.) The episode ends by adding insult to injury, saying that “robbers took away his bones, mistaking them for something else.”

3 Before establishing his own position, Yāska quotes an earlier grammarian named Kautsa who argues that Vedic mantras are meaningless and then attacks him point by point. Still, the heterodox position is preserved within the orthodox text.

4 The modern anonymous Sanskrit commentary from the 1945 edition edited by Shastri Murari Lal Nagar as a part of The Princess of Wales Sarasvati Bhavana Texts Series states that the other breast is meant. But even if that is the primary meaning, an ambiguity remains.

5 This has been explained in verses 1131and 1173 above.

6 Martin Heidegger actually explains this pretty well in §16 of Being and Time: “The modes of conspicuousness, obtrusiveness, and obstinacy have the function of bringing to the fore the character of objective presence in what is at hand... in a disruption of reference—in being unsuitable for...— the reference becomes explicit.”

7 The twitter-bot @metaphorminute easily creates new metaphors, but they are often unrelatable. Alexandra Tatarsky’s essay in the Hypocrite Reader is insightful here.

8 I have been told that Anne Carson talks about this very thoroughly in her book Eros the Bittersweet, but, much to my chagrin, I have been unable to find a copy in Mysore.

9 This is a point J.Z. Smith makes in Drudgery Divine.

10 Symbola were broken knucklebones used to mark a pledge of one’s money, one’s word, or one’s identity. The knucklebone would be broken in two, and each half would symbolize the other matching missing half and the ideal whole. The presence of one half would be signified by its very absence.

11 Trotsky spends his entire career looking for the proper slogan—one that will convey revolutionary values while resonating with a wide audience. The tone of his rhetoric becomes desperate as he is forcibly removed from Russian politics; he is bitter but still desperately hopeful. All he has now are words, and those will have to suffice. At the height of his career (before Lenin died), he was looking for “a transitional slogan, indicating a way out, a prospect of salvation, and furnishing at the same time a revolutionary impulse for the future” (Is The Time Ripe For The Slogan: ‘The United States Of Europe’?). By his time in exile, he is proclaiming, “Lenin’s thought must not be taken dogmatically but historically. Lenin brought no finished commandments from Mt Sinai, but hammered out ideas and slogans to fit reality, making them concrete and precise, and at different times filled them with different content” (The Permanent Revolution). On a personal note, the only time my family has entered the books of world history was when my aunt Sylvia Ageloff, a social worker from Brooklyn, was seduced by an NKVD assassin in Paris and then unwittingly led him to Trotsky in Mexico. Trotsky of course ended up with an icepick in his head. It sums up my family pretty well: easily seducible and trusting enough to allow for politics to seep into our lives.

The Hypocrite Reader is free, but we publish some of the most fascinating writing on the internet. Our editors are volunteers and, until recently, so were our writers. During the 2020 coronavirus pandemic, we decided we needed to find a way to pay contributors for their work.

Help us pay writers (and our server bills) so we can keep this stuff coming. At that link, you can become a recurring backer on Patreon, where we offer thrilling rewards to our supporters. If you can't swing a monthly donation, you can also make a 1-time donation through our Ko-fi; even a few dollars helps!

The Hypocrite Reader operates without any kind of institutional support, and for the foreseeable future we plan to keep it that way. Your contributions are the only way we are able to keep doing what we do!

And if you'd like to read more of our useful, unexpected content, you can join our mailing list so that you'll hear from us when we publish.