Victoria Giang

Constructing the Lathe of Heaven

ISSUE 96 | PROPHECIES | JAN 2021

Zhinan Temple 指南宮. Although this temple now houses many gods, the original and most important deity of this temple is Lu Dongbin.

Source: Author’s Photo

Am I a man who dreamed I was a butterfly or am I a butterfly who is now dreaming he is a man? Let this acid trip butterfly dream of Zhuangzi serve as an elementary introduction to a strain of Chinese philosophical thought about reality and its converse, the dream. Surrendering and allowing understanding to stop before what can’t be understood is a valiant position for the quintessential classical Daoist intellectual. Such a surrender may seem like a weakness today, as increasingly minute areas of biological existence are reinterpreted as quantifiable elements, produced as data, with an eye toward optimization. This ever-expanding archive runs parallel to capitalist imperatives and the headlong rush of unlimited economic growth. The two, scientific progress and economic expansion, grow like Italo Calvino’s invisible city of Valdrada, a city both rising above a lake and appearing in it, “living for each other, eyes interlocked, with no love between them.”

Historically, dreams have not been viewed as topics for serious scientific inquiry (Freudian and Jungian dream analysis both represented controversial early attempts). While dreaming is universal, it’s difficult to determine where it stops being a strictly natural phenomenon and starts to become a cultural phenomenon. Even something as “natural” as rapid eye movement was discovered to be influenced culturally; a sleep study found that REM was primarily a horizontal motion for a group of German urbanites but was a vertical motion for a group of forest dwellers.

My own interest in this area was piqued after collecting multiple accounts of dreams from the local community I study in Northern Taiwan, in relation to my fieldwork on a local deity. While at first, the dreams that I heard and read about seemed extremely imaginative and unique, I began to notice that the more that I encountered, the more formulaic they appeared. Things that I considered remarkable once-in-a-lifetime occurrences, such as meeting and speaking with a god, were in fact surprisingly commonplace. Then there was the lab, the dreary office where I went to work everyday, that seemed, at first, like a refuge of pure science. We were developing experimental software and hardware for medical imaging, and there was always an atmosphere of gentle pressure to discover a commercial hit. As it turns out, this is a common experience in a lot of research laboratories. By chance, I stumbled upon the research of Professor Yukiyasu Kamitani, who was using MRI machines to study dreams.

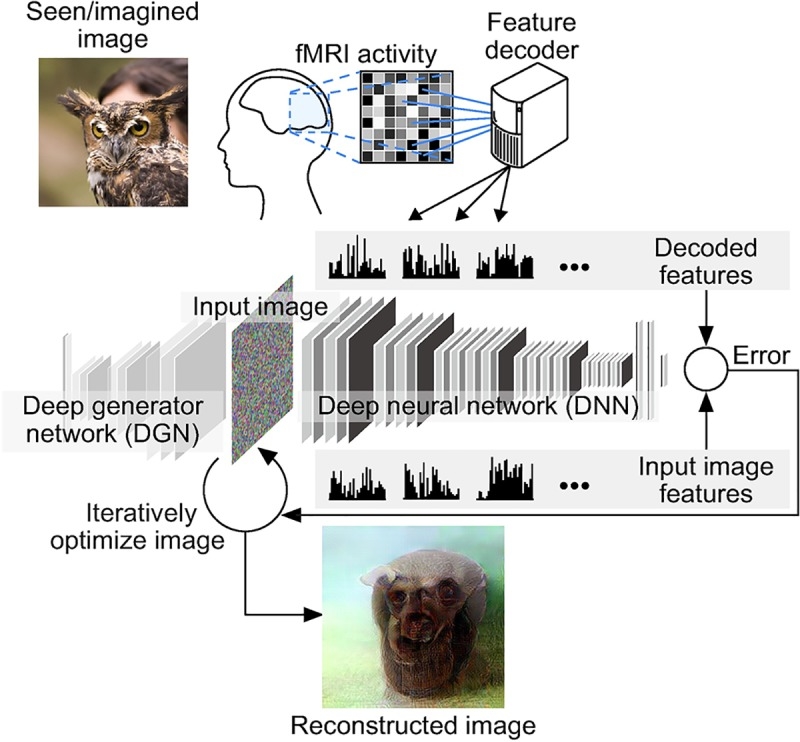

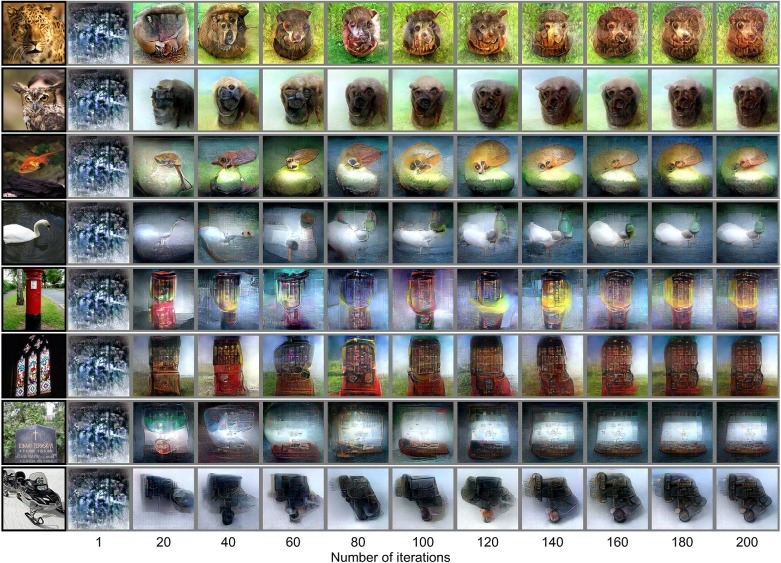

The computational neuroscience research laboratory of Prof. Kamitani in Kyoto University has been attempting to reinstate dreams as a productive field of scientific inquiry, and he and his group have found success so far with their interpretation. They initially found fame in 2012 for an experiment in which they compared fMRI brain scans of dreaming subjects with scans taken when the subjects were awake and looking at photographs of certain common items: a plane, a house, a man, a woman. A few discrete categories were created, reflecting the imagery that their subjects might dream up, all of which was primarily visual, and mostly considered arbitrary. Whether the dreaming subject saw her long-dead grandmother or Guanyin Bodhisattva, both of these apparitions would be categorized in the same way, as if the subject was seeing something that fit into the category “woman.” This simplification is necessary to run any experiment, but it ironically served the purpose of defining the dream in advance. By comparing the data from the waking subjects with the live data from dreaming subjects in the MRI, researchers could then, with a reasonable degree of accuracy, predict what a patient was dreaming based on her neural activity. They could even make rough images of the dreams using a deep learning algorithm designed in the lab. The images reconstructed from the subject’s brain waves looked like warped versions of the original photos, arresting shapes that at times break into surrealism.

The schematic of Professor Kamitani group’s deep image reconstruction algorithm.

Source.

Examples of the deep image reconstruction algorithm in action.

Source.

Journalism regarding scientific activities is often derided for being overly optimistic, exaggerating the applications and possibilities of certain developments. This case was exemplary, with professional and amateur journalists both proclaiming that though science (and, by extension, the rest of us non-experts) understands little about the nature of dreams, we were coming closer to cracking the code that would reveal to us their real purpose. Many were quick to sketch out a future in which dreams could be projected onto a screen, a future in which psychiatrists could more intimately examine their patients; others heralded the reconstructions as the first photographs of dreams. Dreams were presented as a wilderness, an empty frontier onto which new interpretations and applications could be projected, such as how to improve memory or soothe trauma.

The word frontier should alarm us. The pattern of emptying a place or an idea of all prior meaning in order to occupy it is that of the colonial venture—an act of techno-scientific colonization over the human body. This is the road paved by the bioeconomy, which develops so-called “natural” phenomena into commodities. Bruno Latour’s nature-culture hybrids, like gene-edited mice or war pigeons, exemplify for us how the so-called “natural” is never really something disconnected from humanity but is merely a functional category that helps smooth a surface for “cultural” invasion, the occupation of one set of cultural meanings at the expense of all others.

That science understands little of dreams may be true, but it doesn’t mean that dreams are either meaningless or definitively unknowable. They have a wide assortment of cultural meanings throughout time and space. In the Sinosphere, dream interpretation was developed as a discipline in its own right, from Chinese antiquity and continuing up until the present day. Dreams could have prophetic functions. In modern day Taiwan, for example, it is common knowledge that if someone you know dies in your dream, it means he’s about to make some money. Alongside this one-to-one system of dream analysis, there exists the notion of dreams as a stage where real action happens. In these dreams, your soul may travel to another world or a place between worlds where you are then able to meet your long dead relative or an immortal.

Zhuangzi is the representative thinker from Chinese antiquity on dreams, in scholarship and in popular culture. For example, Ursula Le Guin’s 1971 novel, The Lathe of Heaven, about a man who was able to control the future through his dreams, took its name from one of Zhuangzi’s more artistically translated aphorisms: “to let understanding stop at what cannot be understood is a high attainment. Those who cannot do it will be destroyed on the lathe of heaven.”

The ancient philosopher has entirely monopolized this topic, to the detriment of another popular figure in the Chinese cultural pantheon: the immortalized Tang dynasty poet, Lu Dongbin. Usually depicted as a handsome young man with long black hair and a fondness for drinking, Lu Dongbin is both the author and subject of hundreds of folk and literary tales. For centuries after his death, he continued to write poetry through the possession of spirit mediums in automatic writing clubs, and in these legends and poems, his association with dreams is a recurrent feature. He is lord and master of dreams, even into the present.

In literature, the dreams that Lu Dongbin gave others always led to their seeking immortality. He allowed dreamers to let go of their attachments in one world in order to transcend into the next. The most famous of these stories is the “Yellow Millet Dream.” In this tale, a man wants to go to the capital to take the exam to become an officer. He’s failed before, so he’s got test anxiety. He stops at a tavern for the night and orders a bowl of porridge. An old man at an inn lends him a charmed porcelain pillow, which he sleeps on and dreams that he not only passed the exam but achieved high marks and a coveted position. He marries a rich and beautiful girl, and they have lots of kids, and later, grandkids. He’s got it made until some of his associates become jealous of him and frame him for corruption, so that he is thrown in jail and ends out his days there…until he wakes up. The millet is still cooking, his porridge isn’t even ready yet, but in all of that time he lived out a whole life. The old man seems familiar—it’s Lu Dongbin himself!—and he asks the young man to come with him and become an immortal, since all the striving and ambition in the world, even when fulfilled, isn’t worth a damn.

A Song Dynasty painting of Lu Dongbin.

This legend is typical. He has several more with the same theme: giving a man bags and bags of gold until he feels completely bored of money; giving a businessman a dream of being born a mute woman and tragically losing a child so that he loses his zest for living. All of them are seduced by his gallantry and accept his invitation to immortality, giving up on the world.

Outside of literature, though, these legends and their particular morality have little to do with what people in the real world seek out Lu Dongbin for. Of the famed Eight Immortals of Daoism, he is the most popular, and his cult is still large. People have come with all kinds of concerns: to heal plagues, pass exams, or acquire sons… However, these days, they tend to look to him largely for financial advice. This desire for material success in the here-and-now was what led a small temple to Lu Dongbin in the mountains of Taipei to blossom into a sprawling, palatial complex.

In this temple compound, clouds obscure the city below and cover the ground in a fine mist. The blue smoke of incense is thick in the air, and the sounds of water from fountains and waterfalls play in your ears. The place itself conjures up the unreality of the dream state for which Lu Dongbin is so famous. There are several little rooms off to the sides of the altars where consultations are held between ritual experts and those seeking the help of the divine. The Daoist priest communes with the forces of heaven on your behalf, your contact with the divine becoming a byproduct of his. Lu Dongbin’s temple is unique in that it offers an even more direct form of contact. There is a small room reserved for worshippers who need to ask a question to the god directly. They go in there and fall asleep, and as they sleep, they dream. Since Lu Dongbin is present in the temple, it is highly likely that he will contact the dreamer. Upon awakening, the dream will be interpreted on your behalf by one of the resident experts. This form of communication is even closer than praying to the idol or hearing the recitations of spirit mediums possessed by him. It’s the closest that you can get to seeing him in the flesh.

Unlike the “Yellow Millet Dream,” the dreams that devotees want operate on different terms. They answer purely pragmatic questions: Should I buy this apartment or that one? Should I develop this plot of land or that? Is my new business partner trustworthy? They, like the neurological researchers described previously, define the parameters of the dream in advance. The content of the dream that they receive is only important insofar as it gives them a clue about how to maximize their personal profit.

The temple is an institution and what happens in it, regarding the gods, follows a different logic than that of the family. However, the relationship between family members and ancestors, spirits, or immortals is also frequently navigated through dreams. There’s a young office worker and artist that I am close with, a Taipei native with a love of Taiwan’s traditional rituals and customs (incidentally, he was the one who suggested I undertake a more detailed study of the local religious life of our Taipei suburb). For the sake of anonymity, we’ll call him Mr. Yeh. He has recounted for me, on several occasions, the story of a dream his grandmother once had. She was walking around the first floor of her home when she saw a teenage girl sitting at the bottom of her staircase, a girl with beautiful long black hair. The girl called her mom.

“Mom,” she said. “I’m bored and lonely. No one visits me. I want to get married.”

His grandmother, at this time in her fifties and still active, with a lucid mind, could see the girl directly, vividly, and she knew that this was her daughter who had died as an infant. It had been seventeen years since she had passed away, and she had grown up on the other side. It was natural that she would want to have a husband. She found a neighbor who was willing to take her as his spirit bride, and the girl seemed pleased enough with that, showing her satisfaction by disappearing from her mother’s dreams.

Mr. Yeh’s grandmother and some of his aunts were the best-known in their family for having these sorts of dreams—dreams in which their relatives would appear to them and ask to be remembered. This would provide security for the future, since without being properly cared for, these souls would be liable to create trouble. These family matters are akin to burial practices, in which the siting of a grave would have continued real effects on the family, guiding the direction of their future.

Dreams, then, in popular practice, are venues in which the skillful can negotiate with their ancestors for future security or liaise with deities who can perhaps give them stock tips. Although they are sometimes portents or prophecies, they are intimate ones, rarely of the type given by Liu Bowen, writer of the famed “Shaobing Song,” whose prophecies implicate the whole world. However, dreams are generally, if not always, meaningful domains of activities which have impacts in the waking world. They are not merely the residues of a consciousness working itself out during sleep. In traditional belief, dreams are not an unknowable terrain, and although they imply an unreality, a difference between them and the waking world, they are thought of as a site of communication between our world and another.

Just as the older generation of Mr. Yeh’s family takes for granted that their deceased relatives visit them in their dreams (a perspective which persists globally as an interpretive mode, not merely an uncorrected superstition), the popular-science journalists and devotees of scientism take for granted that the images they see produced by Kamitani’s lab are the dreams themselves, the real article, dispatches from an unexplored world.

Neither one of these modes is more correct, although it is noteworthy that, as I collected these accounts of dreams as part of my field research, I was immediately more skeptical of the traditional Chinese version as it was presented to me. In the interviews that I conduct, I tend to look for the ways in which the stories really mean something else. For example, that dreams about a dead unmarried daughter who needs to be married are really illustrating the way that women are complicit in upholding patrilineal descent, accessories to their own marginalization. Where someone else might say that such a dream is natural, from my outsider’s perspective all I see is culture. In all of these cases, the parameters of what a dream can be are set in advance; and after setting them, we often forget that they exist.

These parameters, such as Kamitani’s cognitive categories and the computer program’s linking of images to neural activity, are usually created for the sake of convenience only, but upon seeing the images, it’s easy to believe that these are, somehow, an unimpeachable projection of what’s in our heads. That is how most journalists and writers understood it, as a “decoding” or a “reading” of the brain. And that’s exactly how I took it when I read about the laboratory years ago.

Traditional cosmology is often viewed as exceedingly conservative to the point of backwardness, but scientific inquiry, while it has undeniable merits that I also value, often falls disappointingly short of ideals of openness and progress. The presentation of science as a system that will always serve to decrease prejudice and liberate us from intellectual myopia ignores the fact that this discipline is subject to the same market logic that ensnares the rest of us. Developments are more likely to follow money than necessity, so treatments for restless leg syndrome can be developed faster than ones for malaria or another tropical disease. Likewise, sleep, and by extension, dreams, is a billion-dollar business. The ability for labs researching dreams to gain funding and the public interest that enables more funding depend on this.

The marginality of other viewpoints on dreams, the way that they are easily discarded as if they didn’t exist or didn’t count (“no one knows the true reason why we dream”), is part of a broader trend of enfolding more and more biological processes into the sphere of a particular kind of understanding. This is often, if not always, with an eye toward using them as building blocks for the bioeconomy, the commodified branch of the life sciences. Kamitani’s lab is then a representative example of this broader trend of the scientific penetration of daily life, of drawing all of our bodily activities into the sphere of one specific type of inquiry: quantification, prediction, and ultimately, optimization. A step closer, perhaps, to the fatally divine “lathe” of Zhuangzi’s aphorism. In East Asia, this process is even more urgent. Most East Asian states sponsor the development of the biotech sector as a way to avoid stagnation, with Japan and its lost decades offered up as a particularly grim example of what the future could hold for its neighbors.

I often sleep on my problems, so perhaps I owe any insight I’ve gained—that my own skepticism, and sense of the cultural foundation of knowledge, is itself just another lens—to sleep itself. In other words, it’s possible that I’m indebted to the dream deities mentioned earlier. And while the formal reduction of dreams may be valid in the laboratory, I do wonder what would happen if the two worlds collided. Would this even be possible? Perhaps one person, sitting in that MRI machine and having their brain scanned, may one day dream of the immortal Lu Dongbin. Upon being awakened by the researcher who asks them what they dreamed, they find that the answer defies the categories given—that they’ve been given an understanding that defies itself.

The Hypocrite Reader is free, but we publish some of the most fascinating writing on the internet. Our editors are volunteers and, until recently, so were our writers. During the 2020 coronavirus pandemic, we decided we needed to find a way to pay contributors for their work.

Help us pay writers (and our server bills) so we can keep this stuff coming. At that link, you can become a recurring backer on Patreon, where we offer thrilling rewards to our supporters. If you can't swing a monthly donation, you can also make a 1-time donation through our Ko-fi; even a few dollars helps!

The Hypocrite Reader operates without any kind of institutional support, and for the foreseeable future we plan to keep it that way. Your contributions are the only way we are able to keep doing what we do!

And if you'd like to read more of our useful, unexpected content, you can join our mailing list so that you'll hear from us when we publish.