Joshua Reaves

Bois Caïman: Bringing God to Earth

ISSUE 96 | PROPHECIES | JAN 2021

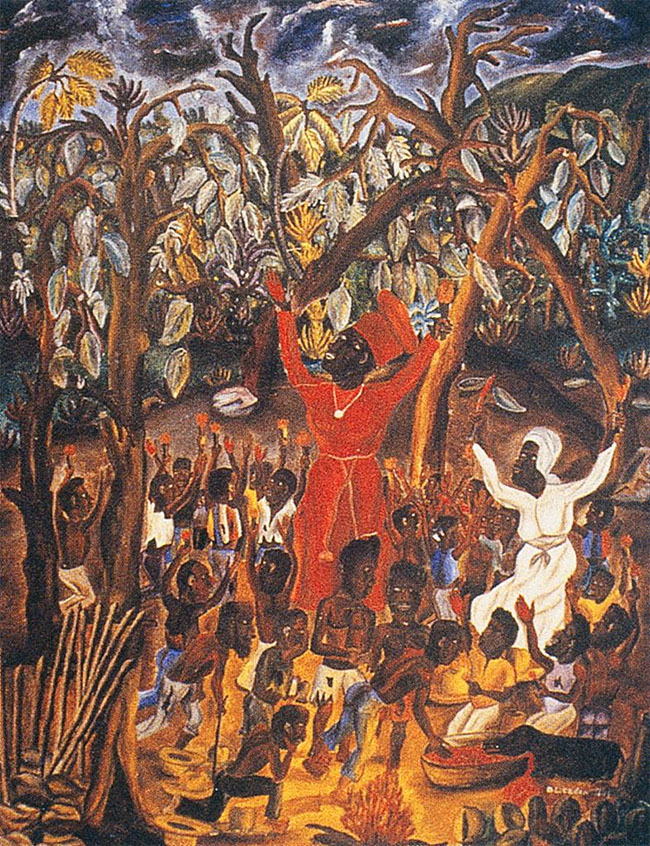

Bwa Kayiman Haiti 1791, Nicole Jean-Louis 1924

God who created the sun

which shines on us from above,

who raises the sea,

who makes thunder rumble,

who hides in a cloud.

Hear me well, all of you.

He is there watching us,

He sees all that whites do.

The white God asks for crimes,

ours asks for good deeds.

God who is so good,

He asks vengeance of us.

He will lead us,

He will give us assistance.

Throw into the jungle

the image of the white God:

He is too thirsty for the tears in our eyes.

Listen rather to the freedom

that is beating in our hearts:

Boom . . . boom . . . boom . . . boom . . .

With these words and the warm blood of a Creole Pig, Dutty Boukman ushered in the liberatory struggle later known as the Haitian Revolution. Boukman was a Vodou priest and an early revolutionary leader, his fiery zeal for freedom invoking the righteousness of Black freedom against a loathsome white God. This legendary call to arms took place in the Bois Caïman (Alligator Swamp) of Northern Haiti, in the midst of a ritual shrouded in myth. Under the night sky of August 21, 1791, hundreds of enslaved Black people gathered in the recesses of this swamp to celebrate the ritual onset of revolution.

Details of this event itself are scarce, living across the whispered breaths of excited Black Haitians and fearful white colonizers since its purported date. However, it is generally told that the days leading up to this August night had been full of auspicious signs, both from God above and from the beating hearts of Haitians. The long periods of thunder, crashing waves, and powerful winds were taken as good omens, further evidence that Boukman indeed had the power of a Black God on his side. Boukman was joined in this ritual by Vodou priestess Cécile Fatiman, rumored herself to be a fearsome Dahomey Amazonian warrior, and by the hundreds of slave organizers from the plantations that surrounded the northern capital of Cap-Haïtien. The ceremony marked a change in spirit for Black revolutionaries, who had been isolated from each other until this meeting.

Fatiman and Boukman led the Bois Caïman crowds in a ritual for the Petro Loa, especially honoring the mother of this family, Ezili Dantor. The Loa, spirits that inhabit Vodou’s diverse pantheon, are themselves divided into nations (nanchons). Most nanchons, such as Kongo, Rada, and Nago, hail directly from African nations sharing their names; Kongo from Congo, Rada from Dahomey, Nago from Yorubaland. These loa nanchons are eldest in the hierarchy of spirits, carrying age and knowledge from the mother continent. These Old World Loa are known for their cool, calming wisdom and moral guidance. By contrast, the Petro nanchon, and mother Dantor, are the loa of the New World, born from the cracks of whips and gunshots that defined the daily oppression of Haitians. They hail from no particular nation of Africa, but represent the experiences of all Africans within Haiti, as the cruel barbs of slavery united diverse African tribes and beliefs. These Loa are known for their boldness: the youth of their identity and the pain under which they formed left them fiery. They are Black gods, standing in unity with the African nations of spirits as a result of their Blackness. They are younger, different from the other nations, but fastened together by their shared history and resistance to the oppression of the white god. The Petro were angry for the souls of Black folk, and it was to these angered Loa that the would-be revolutionaries prayed. They danced, fast and free, guided by whistles and the sound of gunpowder. And Mama Danto heard the cries of her children.

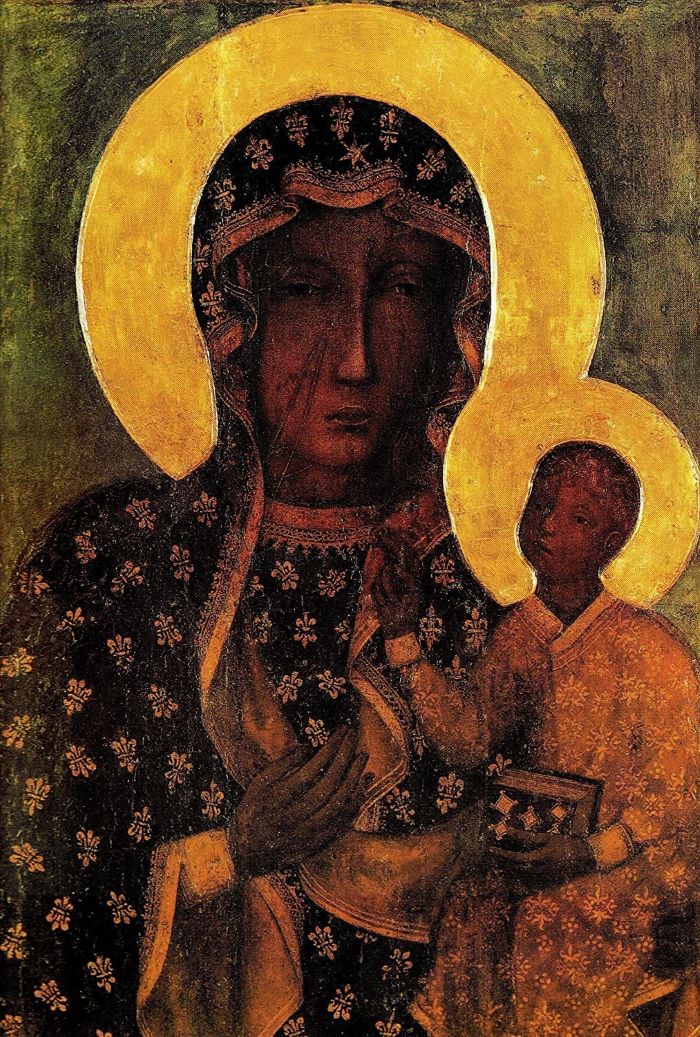

The Black Madonna of Czestochowa, a Polish icon later accepted as a representation of Ezili Dantor

The ritual of Bois Caïman approaches a crucial contemporary issue. For Black people, resistance to white supremacy is a part of living. Black culture is a culture of resistance, and the memory of the Black revolutionaries of the Haitian Revolution offers hope to Black revolutionaries today, proof that victory is possible against a racist system. But this victory was not clean or simple, and Black history has demonstrated a number of contradictory responses to the problem of white supremacy. The struggles of Haitians demonstrate how internally conflicted Black revolution, and Blackness itself, can be, then and now. During the intricate unfolding of the revolution, many Black people, with various class backgrounds, ideologies, and actual positions on slavery, fought not only against their colonial oppressors but against each other. And yet these factions all contributed to what became the greatest victory against colonial slavery in known history.

The day after the ritual, the revolution began in full force. Within days, plantations had been burned to the ground. Within months, what had started as a ceremony in a swamp had become a full-fledged civil war on the island. But Bois Caïman was a turning point in the history of Black resistance, not its origin. Black people had been planting the seeds of revolutionary struggle since they had been dragged from Africa in chains. The moment of enslavement birthed Black resistance, a critical component of Black identity through the present. Haitian Vodou pays tribute to this exact moment through song, as the traditional hymn Sou Lanme (performed here by Haitian artist Yanick Etienne) bears witness to the Middle Passage’s genesis of explicitly Black struggle.

On the ocean we are sailing

Agwe Tawoyo1

There’s a time when they’ll see us

On the ocean we are sailing

They took our feet

They chained our wrists

They dropped us in the bottom

They took our feet

They chained our wrists

They dropped us in the bottom of the ship

On the ocean we are sailing

Agwe Tawoyo

There’s a time when they’ll see us

Slave ship under the water

The ocean is bad

The ship is broken

It’s ready to sink

Slave ship under the water

At the bottom of the ocean

It’s covered in water

It’s ready to sink

In the bottom of the ship

We are all one

In the bottom of the ship, a multitude of African cultures, people, and lives became historically aligned; numbers of nations, dozens of languages, and countless spirits were joined syncretically through these acts of pain and their struggles against it. Blackness, through a shared experience of oppression and history of resistance, is naturally composed of diverse trends and expressions of resistance. And as Black self-determination became possible throughout the course of the Haitian Revolution, the heterogeneous cultures of Black resistance across the country came clearly into conflict. Take, for instance, the exchange between two revolutionary Haitian leaders, Toussaint Louverture and Macaya. Their conflict revealed the fractious tensions inherent to revolutionary struggle. Each of these leaders serve as both commanders of armies and as symbols of their philosophy of Blackness.

On the one hand stands Toussaint Louverture, the Black Spartacus. Louverture stands at the center of the popular image of the Haitian Revolution: CLR James’s Black Jacobins, to which practically all non-Haitian study of the Haitian Revolution owes a great deal, is practically a drama with Louverture as the tragic hero. This is not without reason—his military skill and political acumen helped to transform the different bands of enslaved soldiers into an incomparable military force. From his emergence in the revolution as a medical aide in 1791 to his eventual betrayal at the hands of Napoleon’s France, Louverture left a complicated political legacy in his wake, held together by a uniquely Black view on his identity as a French subject.

As the Haitian Revolution took place alongside the French Revolution, Haiti itself became embroiled in the civil war of the imperial metropole. Across France, starting in 1789, the French Revolution began in earnest, and France found itself divided between the monarchists and the democratic rebels, the Jacobins. The war at the heart of the French Empire spilled over to France’s colonial crown jewel, Haiti (then known as Saint-Domingue). After three years of the slave rebellion in Haiti, the French Jacobins finally outlawed slavery in all French colonies, outraging the white colonists still on the island. In response, Louverture found it politically and philosophically pressing to declare his intentions towards France. With his own forces growing against the French institution and colonists, his armies found an ally in the Jacobins’ French Republic, for a time. He came to see himself as an enforcer of French will, and himself a French citizen; citizenship and freedom were not denied by France itself, he argued, but by the heartless white colonists that controlled the island. This is summarized in a famous line of his 1801 constitution,

“Here, all men are born, live, and die, free and French.”

Haiti would be a land without slavery, but it would still be a French land. Being French did not mean whiteness to him; rather, it was a critical location in which abolition could be won. Louverture saw his struggle for freedom waged both within and against the French state—Blackness was a site of resistance against slavery, and French citizenship a basic right for Black people on the island.

While Louverture’s professional army waged war across Haiti, African warbands of maroons fought their own battle for Black freedom across the north. Maroonage, the act of escaping slavery and forming communes with other escapees, was so widespread that even before the uprisings following Bois Caïman, 5% of African slaves in Haiti were runaways at any given moment. Maroons also formed self-sustaining encampments, where leaders from African nations preserved their religious traditions and the ways of life that enslavement had worked to destroy. Maroon warriors were widely feared in the colony for their association with the slave revolts, most famously with Boukman in 1791 and François Mackandal’s earlier, similar revolt in 1758.2 Throughout the course of the revolution, these maroon bands (many of which predated any significant revolutionary force) took on varied, contradictory roles. Maroons were no slouches at combat against the imperial forces of France and Spain, and their legendary abilities as guerilla warriors across Africa and Haiti helped them stay unconquered by any force that would threaten them. Some maroon warriors themselves came to oppose Louverture’s French Republic-backed army, putting their faith instead in the armed patronage of the nearby Spanish. Among these maroons was Macaya, a Kongo-born military leader, who spoke to his own views on being a Black subject of France:

I am the subject of three kings: of the king of Congo, master of all the blacks; of the King of France, who represents my father; of the king of Spain, who represents my mother...These three kings are the descendants of those who, led by a star, came to adore God made man…[if I] went over to the Republic…[I would be] forced to make war against my brothers, the subjects of these three kings to whom I have promised loyalty.

While Macaya shows fealty to the Spanish and French royalty, he sees Blackness as outside their purview. The slaveholding imperial powers are not the “master” at all—only an African nation, with an African king, can hold Black identity. Blackness is thus a totally independent subjectivity, located solely within Africa. While Black people may swear allegiances with and fealty to other nations, Black people enter into these relationships as members of the Kongo Kingdom, equal under the eyes of God. This placed Macaya both philosophically and politically at odds with Louverture—the maroons harassed Haitian armies and cities throughout the entirety of the revolution. Moreover, this placed their conception of Black identity at odds; Black Haitians were deserving of the rights of French citizenship, by Louverture’s estimation, while Macaya fought for a truly African kingdom and citizenship for his people. Black identity comes to encompass both of these positions—Black Haitians can be both Black French, and thus resist the former whiteness of Frenchness, and fully African, resisting the system of colonization as an outside force. Blackness runs rivers, long and spread.

It gets more complicated: both of these factions participated in the slave trade before, during, and after the war. Louverture himself was a slaveowner prior to (and perhaps throughout) the revolution, accruing enough wealth to make his white neighbors nervous. Later, he defeated an army of free, mixed-race Black people even more loyal to France than himself and finished the unification of Haiti, after which he acted to reinstate the plantation system (and thus, effectively, slavery) in order to jumpstart the failing economy. Maroonage as a way of life offered respite from slavery during the colonial period and its reinstitution under the early Haitian leaders. Maroons preserved indigenous and African religious practice, practiced self-sustaining farming, and fostered a culture of independence from the colony that allowed maroonage to prosper even after emancipation. Among the maroons, after Haiti’s independence, independent agriculture across the island flourished, despite the efforts of the revolutionary government, which sought the re-emergence of the plantation regime. But maroons did not free every slave they came across; Macaya’s maroon community, in particular, was found to have sold its Haitian enemies into slavery in Spain after military victories.

Le Marron Inconnu, by Albert Mangones, is a contemporary tribute to the maroons of the Haitian Revolution in Haiti’s capital city, Port-au-Prince.

After its revolution, Haiti would become neither a new Kongolese nation or a free French colony. The realities of the war quashed any hopes for amnesty from the French Empire; Louverture found himself locked in a three-way battle between the French, himself, and those Haitians who resisted his reinstatement of forced labor. Before his death in France, Louverture acknowledged that he was but one member of a revolutionary struggle:

In overthrowing me you have cut down in Saint-Domingue only the trunk of the tree of liberty; it will spring up again from the roots, for they are numerous and they are deep.

With Louverture gone, it was Jean-Jacques Dessalines who took command of the revolutionary forces. Dessalines had been a commander within the revolution for a decade, Louverture’s most trusted lieutenant, but defected in the midst of the war. Under his leadership, the Haitian troops eventually achieved a lasting victory over the French. Whites were banned from owning property and the remaining colonists were executed or exiled; Macaya’s maroon warriors were crushed for supporting the French; and the newly-crowned Emperor Dessalines could begin to build a nation despite economic isolation.

With the 1804 constitution, Dessalines established a third way to be Black on the island. Rather than positioning the Blacks of Saint-Domingue as French citizens or the subjects of an African kingdom, he renamed the colony Haiti, after the indigenous Taino name for the island. And with the same decree, he declared that Haiti would be Black and autonomous:

We have dared to be free, let us be thus by ourselves and for ourselves.

The revolts that began with an ideal, sung in a secret ritual deep in a swamp, ended with the establishment of a radical new society as the first nation to fully abolish slavery in the 19th century. Haitians had enlisted every means of struggle at their disposal, despite the contradictions between them, to wash away their enslavement. Within this revolution and its legacy, the various realities lived by Haitians led them to view their own Blackness with radical differences. For some, such as Toussaint Louverture, there was a possibility of freedom within Frenchness. Black people had been forced into French servitude and could maneuver from that position. In another perspective, shared by Macaya and the maroons who fought for their own freedom, it is African heritage alone that gives Black people our power. Africans, forced to another continent in chains, have a noble history and connection that empowers us to act. Another position, that of the battle-hardened Dessalines, holds that Blackness is opposition and autonomy. Black people, now colonized, can return neither to France nor Africa; our hope for freedom lies in what we carve out for ourselves where we are. Dessalines’ eventual military victory did not end these conflicts about Black resistance, as many Haitians struggled for freedom on their own terms within and against all Haitian regimes of power.3 As these positions unfolded against each other, revolution did not simply prove or disprove any of them. Each contributed from their own understanding of Black liberation, and it was only through the total sum of their efforts that Haitians ended slavery.

What Haiti offers us is a complex series of battles through the present day. The liberation of all Black people still has yet to be realized—even on the island, it could not be fully realized at the time of the revolution. After his coronation, Emperor Dessalines faced internal crises across the island as Haiti attempted to build, forcibly cut off from the rest of the global economy. Haiti continues to suffer under imperialist extraction and disinvestment today. For modern-day Black organizers, the factions of the revolution of 1791 represent many contradictory ideas, many different avenues from which to approach our own Blackness within liberatory struggle. Perhaps these complications are an essential part of our struggle, of being Black. Blackness is not just African-ness, not just finding a place within colonial subjecthood, not just rejection of all other categories, but the meeting of all of these perspectives within history. The Vodou nanchons are capable of holding these different stories of our shared past together—some of the loa nanchons carry the traditions and wisdom of our African heritage, while others represent our location in the present, cut-off from our heritage and oppressed. These contradictions are held, remembered as a lineage of struggle against slavery. And through the present, this tradition of resistance provides inspiration where individual beliefs cannot.

And the spirit of Mackandal in Bois Caïman

Vodou ceremony

Initiating Haitian liberation[…]

Black Jacobins be smashin’ the myth of white supremacy

Broke their legacy and destiny

It’s time for Dessalines

-“Sak Pase,” The Welfare Poets

1 Agwe Tawoyo is the loa of the ocean, fishermen, and captain of a beautiful ship named the Immamou, which ferries the dead to the afterlife. He is a member of the Rada family of Loa, and is a kind and gentlemanly elder who cries saltwater tears for the souls lost during the Transatlanctic Slave Trade.

2 Mackandal is now another source of national pride for Haiti, represented on the 20 gourde coin and across oral tradition. His knowledge of local herbs, and his potent ability to make deadly poisons, was so extensive that French colonists and enslaved Black people alike thought he commanded “black magic.”

3 Haiti’s early government faced a number of issues, both internally and internationally. It was not diplomatically recognized by any other nations for years after its revolution. In return for recognition from France, Haiti was forced in 1825 to pay a sum of gold equivalent to US$25 billion today. Further conflicts between the literate, mixed race elite of Haitian cities, the self-sufficient, peasant Black farmers of the island’s interior, and different military regimes that fought for control of the island escalated economic and social issues.