Abraham Younes

Beirut’s Unheard Omens

ISSUE 96 | PROPHECIES | JAN 2021

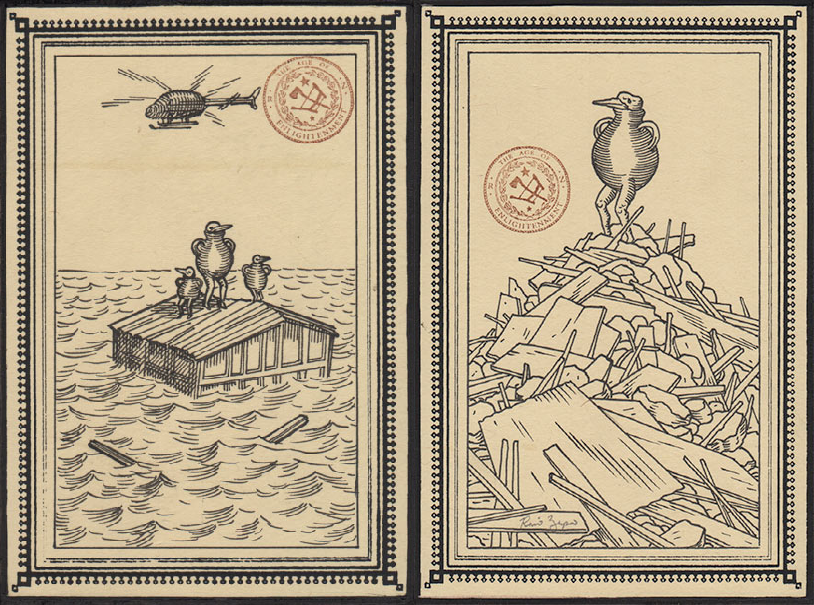

Illustrations by Ravi Zupa.

In July 2015, an unusual story made world headlines: Lebanon was experiencing a garbage crisis. A river of refuse, long and wide enough to be seen from 10,000 feet in the air, snaked for miles through the capital city of Beirut and created a stench so unbearable that hundreds of thousands of people were forced to shutter their windows and avoid the outdoors for weeks. The jarring aerial views of the “trash river” made headlines on CNN and BBC. News pundits around the world marveled at the footage, wondering at how a catastrophe of such proportions could seemingly explode in a matter of days.

The trash crisis put on international display an extraordinary failure of governance, reigniting familiar lamentations in Lebanon about a cultural crisis from within. What could be said about a nation where the state failed to fulfill even the most elementary of public services and safeguards: picking up trash, safeguarding hazardous substances, preventing a deadly and easily foreseeable chemical explosion?

Discussions among people in Lebanon about internal causes primarily centered around corruption and the dominant role of sectarianism in Lebanon’s political system, where wasta—or favors doled out on the basis of family, tribal, and sectarian affiliation—play a decisive role in everything from government employment to electricity access to waste management. To interfere with existing power arrangements in any of these sectors is to confront a labyrinth of mafia-esque power brokers, a hurdle that has prevented social movements in Lebanon from progressing beyond their infancy. (The garbage protests in 2015 lasted only one month, and the short-lived Lebanese revolution of 2019 ended with the reinstatement of the incumbent prime minister, Sa’ad al-Hariri.)

The usual external culprits also received their fair share of blame: Iran and Saudi Arabia, the United States and Israel, each of whom has economically strangled some segment of Lebanese society in service to its geopolitical interests. No matter how much blame was ultimately assigned to any particular actor, the general sense of malaise was pervasive. Imagining the future was impossible without first addressing the bleakness of the present and thinking through how the roadblocks of the current system might be overcome.

These concerns featured heavily in my 2018 interviews as a graduate student doing fieldwork in Beirut, where I talked to engineers, activists, and residents of neighborhoods affected by Lebanon’s ongoing garbage crisis. Three years on from the start of the crisis, the Lebanese government had installed two emergency landfills by the sea that were temporarily keeping another catastrophe at bay. Still, many areas in and around Beirut still did not have routine trash pickup, and tens of thousands of residents continued to rely on open-air burning and informal neighborhood dumping to get rid of their waste. Hoping to write a dissertation and eventually a book on the subject, I wanted as many perspectives as possible on what could cause such a stunning systemic failure and what solutions, if any, were being imagined.

The dissertation never happened, and the author (as is often the case in graduate school) had a rather untimely career change. Still, I was drawn to writing on how everyday people make sense of the garbage crisis: about the effects of failed governance on the collective psyche. After the port blast in August 2020, I went back and listened to those same recordings from summer 2018. Poring over interview transcripts, I found myself returning time and time again to the same conversation, an informal four-hour chat with two fishermen in a Beirut marina.

I am referred to Khalid by an Arabic professor at the American University of Beirut and give him the elevator pitch of my project in a WhatsApp audio message. I am Lebanese-American, a PhD student, here to study the garbage crisis in Lebanon and how it is affecting people like him who relied on clean seawater for a living. Khalid, a part-time fisherman in his mid-fifties who makes most of his money selling fishing and boating equipment to clients up and down the Lebanese coast, immediately dismisses every detail, along with the IRB protocol I am required to read about informed consent and anonymity. He invites me for tea at his marina and says he will do his best to answer any questions I have.

The marina in question is tiny, clearly a local affair, with four small, hand-painted boats docked at a pier no more than 50 feet long. It is mid-July, and the simmering midday heat shows little mercy. Shirtless, grinning, and barrel-chested, Khalid invites me into a shack-like garage under the marina that opens onto the four little boats and the Mediterranean. I look around the garage: a gas stove, a pile of nets and fishing equipment, a rusted bookshelf with more equipment and a few books, and a twin-sized bed in the far right-hand corner.

“Does someone…live here?” I ask.

“The old man,” Khalid says.

When Abu Isa appears a moment later, he shakes my hand and asks if I speak Arabic.

“Don’t you hear us talking?” Khalid says.

“I don’t know, the ones who come from America sometimes don’t,” the old man chuckles. “And where do you live now?”

“Texas,” I say. “Texas,” the old man repeats, and stares at Khalid, then back at me. Abu Isa suddenly bursts into raucous laughter, lassoing his right hand in the air like a cowboy. It takes a while for the old man to settle down, but when he does, he asks me sternly if I want coffee. He rises and lights the stove when I say yes, serves us both, and sits back down to chat.

We start with the two men’s backgrounds. Khalid is Lebanese by birth, a member of the Druze sect1 who, despite being from a tiny mountain village, has lived in Beirut for most of his life. He has a son who lives in Norway and has traveled outside of Lebanon before, primarily to Europe and the United States, where he did a brief stint working on a fishing boat in a coastal town in Florida.

Abu Isa is of Kurdish and Turkish origin. He refers to himself as a refugee, at which Khalid laughs and shakes his head dismissively. Abu Isa grew up in Syria before moving to Lebanon as a young man in the ’60s. He has remained in Beirut ever since.

Khalid is middle class, and Abu Isa is poor, but I can tell the men are lifelong friends, that Khalid would help Abu Isa out with any problem at a moment’s notice. I am surprised to learn that Abu Isa is 88, as he still has a full head of hair and an energy about him uncharacteristic of his age. One biographical detail that sticks out is that Khalid comes from a long line of fishermen, while Abu Isa does not. I ask Abu Isa about this. What led him to pursue an occupation that, in the Arab world, is usually passed down from father to son? He laughs.

“I’m going to tell you something,” he says, “and I don’t ever tell anyone this. But I love freedom. If you put me in a room by myself and close the door, I can’t take it. I need out. And so I often ask myself, what brought me to the sea? I have thought about that many times, and this is the only answer I can ever come up with. The sea is freedom. It is freedom in a way that nowhere I have ever lived has been. Not Turkey, not Syria, not even Lebanon. The sea is freedom, no other freedom compares. But they went and dirtied it all, those sons of bitches. It’s not the same sea it was in the ’70s, the ’80s, even the ’90s. Not even close. This whole country needs to be burned.”

This is the first time Abu Isa brings up politics on his own accord. Each time before, I would try to steer us in that direction, only for him to evade my question or speak in metaphors. “What do you want with those things? I mean, you’re asking me, do I have an opinion on—look, man, I’m afraid they’ll beat me up one of these days.” Abu Isa laughs, but I sense some earnestness to his words. “What do you mean, beat you up?” I asked. “Because,” he said, “the Arabs are dirty, polluted, you see. So of course everything else is going to get polluted.”

Abu Isa still refuses to go much further than this, so I decide to keep to asking more innocent questions until we can get around to more contentious stuff. Both men speak candidly about the difficulty of economic survival: almost all fishermen in Lebanon have some second source of income, and everyone has at least some days out on the water where they make no catches at all.

“It’s like a desert,” Khalid says. “Some places, you don’t see a single fish. And the rare catches, the ones that really bring good money to the fisherman, those are long gone. The grouper, the snapper, sea bream. Lobster and sea urchin. All kinds of oyster. All gone, no more. Spotted trout. Very rare to find. And mullet is a good restaurant fish, people always loved those. But not many left, especially since the dumping in the sea started to get bad.”

Abu Isa talks about inflation, how one needs to make twice as many catches with half as many fish to make up for how expensive the equipment had become. “Back in the days of the lira, you know? It was cheap, a trawl used to cost you maybe five liras. Now it costs you $100. Today, if a young man comes and tells me, ‘I want to work in the sea as a fisherman,’ I tell him, ‘For what? Between the motor and the nets and the boat, that’s $10,000. And then once you have everything, you go down there and some days you don’t catch even a kilo of fish.’”

“Why do you think there are so few fish?” I ask. Khalid immediately brings up the two emergency landfills by the sea that the government have created as a temporary solution to the garbage crisis. “I mean, their ‘solution’ since 2015 is to have these big dumps by the shore, you know, because they can’t agree on where to put it inland. Okay, well, how is that possible? There isn’t another country in the world that dumps its trash by the sea.”

I doubt this privately but keep quiet. I know from my own research that most of Beirut’s trash from 1994 to 2015 was hauled to a valley located south of the city. Residents of several villages neighboring the dumpsite had complained to the government for years about high rates of asthma and lung cancer, finally mounting a campaign in 2007 that went unheard by the government until summer 2015, when demonstrators blocked off the entrance and refused to let the garbage trucks enter.

“Most of all, really, because of wlad haram,” Khalid says. Sons of bitches. “I mean, you will run into trouble wherever you put it. Like, if you’re going to put it near Ouzai, for example, most of the people in that area are Shia. If you go to Ouzai and say, ‘This is where we are putting a new dump,’ they are not going to stand for it. Go to Saida, for example, that’s a Sunni area. They’ll tell you, ‘Ah, you’re against the Sunni here.’ You want to put this on the Sunni. You want to put this on the Shia. You want to put this on the Maronites. You see how they play it?”

What Khalid is saying here makes sense. No single sectarian community wants to accept the majority of the trash from the other communities. I had puzzled initially over why residents of the valley south of Beirut had accepted a large dumpsite in the first place until I discovered that the area around the dump was an unusual mosaic of religious and ethnic groups without any clear majority, making it difficult for them to have much sway in the government (more on this below). In most Lebanese villages, one religious sect dominates. Even Beirut proper is divided into Sunni, Shi’a, Maronite, and Greek Orthodox-majority neighborhoods, so that any dump site in or around the city is almost certain to affect one community disproportionately.

Khalid’s point brings to mind not-in-my-backyard (NIMBY) syndrome in the United States and how the same attitudes here tend to reinforce environmental inequality, especially in urban areas. In the United States, however, class and race are the primary fault lines in the population’s geographic distribution. This means that the burdens of pollution and toxicity can often be dumped on disempowered groups, with what resistance there is being ignored without repercussions for those in power. For example, unlike minority sects in Lebanon, poor Black and brown neighborhoods in the U.S. often lack the political clout or financial resources to fight back when the city sites a new dump near them or a corporate polluter decides to build a refinery near their water supply. Lebanon, on the other hand, is a society where geographic distribution falls primarily along sectarian lines, with no clear majority in the country as a whole and no single race or ethnic group able to force its will on any other. Sectarianism is codified law, with a certain number of seats in parliament reserved for each of the country’s 18 official ethno-religious communities. The number of seats per community are determined using census figures from 1932, the last time that Lebanon conducted a national census, when the balance between communities was relatively even.

It is widely known in Lebanon that these figures no longer reflect the demographic reality, but any parliamentary proposal for a new census is dead on arrival because of the political implications. A new census would mean a possible redistribution of seats in parliament should the current figures differ substantially from 1932, which would almost certainly be the case. An accurate, up-to-date census would upset the delicate ethnic and religious balance that has held since the end of the country’s recent civil war (1975-1990), since Lebanese Christians are widely thought to be significantly fewer in number today. This has made prolonged gridlock a political norm in Lebanese politics, such that infrastructural disputes that might take days to resolve in the U.S. can last years or even decades in Lebanon.

With governmental solutions seemingly impossible, how do ordinary citizens devise their own methods of dealing with the crisis? Khalid tells me that he has tried to lead cleanup efforts with other fishermen he knows, but these attempts are to little avail. “We clean the shore sometimes from Raouche all the way down. But when you start you realize quickly that it’s an endless project. And it’s very exhausting. Like, physically and financially. I mean, how long are you going to try to clean? It costs money, and effort, and time you could spend fishing, to feed your family. At least when we fish we can expect something in return when the day ends. A lot of fishermen now, they’re taking tourists sight-seeing instead, you know. To Ain al Mreisseh or to Raouche. They tell you, ‘I have to feed my family, I don’t have time for this environment stuff.’”

There are NGOs trying to fill the gaps left by the state’s neglect, several representatives of whom I had interviewed earlier that summer. I mention this to Khalid, but he waves his hand at me dismissively. He has apparently tried joining some activist and nonprofit organizations but ultimately became disillusioned with them and left to continue his informal cleanups. “[The NGOs] weren’t doing anything. You know, like for example, you would donate some money and say, ‘Hey, we want to try to increase the fish population.’ They go out and do a study about, I don’t know, dolphins. And they come back and claim, ‘Oh, we did a lot of studies about dolphins, and we found this and that, and blah blah,’ and it’s all a bunch of nonsense.”

This inter-group disconnect is a major theme from my interviews and is most pronounced between those who rely directly on the sea for a living (mainly fishermen and port workers) on the one hand, and activists and educators who are focused on cleanup efforts on weekends and holidays on the other hand. Activists are largely university educated and belonged to the professional class, while fishermen and port workers often have not finished high school. Khalid left both environmental organizations of which he was a part because he feels their objectives are not urgent or serious enough for him to continue donating his money or time.

What Khalid and Abu Isa both agree upon is that large-scale change will ultimately never come from activists or fishermen, no matter how well intentioned either might be or how effectively they clean, but rather, from an “ordered system” (Arabic: nizam, نِظَام). “It’s the same, these problems, with every other government,” Khalid says. “Except Israel,” Abu Isa says. “And Turkey. Turkey has a somewhat ordered system, too. But go to Egypt, to Libya, or to Syria, or here—all of them, you find no such thing.”

I try to get a better sense of the contours of this ordered system they are describing. Is their issue with corruption? Is it sectarianism, the Lebanese version of what we might call “partisanship” in the U.S.? Khalid says corruption is the main obstacle. Abu Isa sees a social safety net as the key missing piece. He says his dream is to live under a system “where you can relax, where the system takes care of you in all matters, or the most important ones anyway, where you don’t have to spend the majority of your day worrying about that stuff.”

I point out that Syria and Egypt, although authoritarian, arguably have a social safety net, maybe even a better one than Lebanon, to which both shake their heads. “There is, but it’s based on favors either way you cut it,” Khalid says. “In Syria, there’s one warlord, see? You have to be in good standing with him to get any favors. Here, there’s a million warlords. Or like we say—a million gangs here. And if the leader of your gang doesn’t like you, for whatever reason, you’re not getting any favors either.”

The conversation sometimes takes abrupt turns, with Abu Isa cutting me off mid-sentence to go off on some unexpected tangent. “Now what do you think of Vietnam?” he says out of the blue. I glanced at him in confusion. “Sorry?” “The Vietnam War, I mean. Millions of people died. They were fighting the biggest power in the world, the U.S., you know. But they didn’t fall behind, when the war ended, I mean. They picked up and moved forward, they have an ordered system, they’re very civilized today. Here we’re still going in circles with religion and all the same bullshit. And all because of what? America?”

In other words, western imperialism and foreign intervention alone do not satisfy Abu Isa as explanations for the garbage crisis and other infrastructural problems in Lebanon. While these forces are perhaps part of a broader historical context, there is more to the equation than outsiders’ role or the lasting legacy of colonialism. In his eyes, Vietnam had “moved forward” under similar pressures and had achieved an ordered system to at least a significant degree: why were the Lebanese unable to do so?

By this point the conversation has gone on for over three hours, and we have a sizable audience, with the other old men and a group of five young boys crowding around the opening to the garage where we are seated. The men have pulled up plastic chairs of their own, while the boys lean in the doorway or peer in from the outside. The conversation is free flowing, with people interrupting and speaking over one another, not necessarily out of impoliteness but out of a desire to get their point across. It is nearing sunset, and it feels like the interview will draw to a close soon, so I want to ask about the future now, about what solutions the men see to the garbage crisis and what policy direction they think the government will or should take.

When I ask about this, Khalid veers to talking about Norway, where his son lives and works on a large commercial fishing vessel. “When I go spend time with him there, we drive for hours on the highway, and you don’t see a single paper on the road. They still have all of their important fish, few have left or died. Not because they are more highly educated than us. Because they implement the rules. The regulations. They can pass any law here, but will people follow it? Will the fishermen or the warlords follow the new law? Maybe some will. But most won’t. And no one will tell them otherwise. You cannot blame the government for everything, you have to blame yourself too. Ourselves. For causing this damage.”

I am taken aback by this point, as it seems to contradict Khalid’s earlier statement about the government being the primary cause of everyday people’s suffering. But Abu Isa seems to agree with him, and then makes a rather shocking statement of his own.

“Listen to me,” he says. “Not in your life. Not in any of our lives—and I doubt that anyone would ever agree, or listen and not just dismiss me as some crazy old man. Never can we talk about the environment until we become human beings. Here, or Saudi Arabia, or Libya or Egypt. It’s all tricks and lies. You know what man’s greatest embarrassment is? You know what it means to lie? There is nothing dirtier. We’re no good.”

Khalid falls silent at this, and everyone watches the old man who, with the sea and the setting sun to his back, appears for a brief moment as an oracle of sorts, some kind of prophet here to warn us of things yet to come.

“There has to be a great war, a plague, something that wipes half of the population out. Something really bad that blows up in their face, something even worse than this, to make them see how dirty they truly are.”

Beach near Beirut. Photo by the author.

I stop the tape, lean forward in my chair, close my eyes. The images from Beirut’s port blast this year are playing back in my mind. It is the summer of 2020 now, and Lebanon has made world headlines yet again, this time for an even more astounding systemic failure on the government’s part: a fire in an industrial warehouse spread, causing more than 2,750 tons of ammonium nitrate to explode inside of a storage facility by the ship channel. The blast claimed over 200 lives, collapsed apartment buildings in a half-mile radius, and shattered windows as far as 20 miles away. In the days that followed, it was revealed that the cargo had arrived on a Russian ship seven years ago and had never been moved elsewhere during all that time despite multiple warnings and letters to the national government from Lebanese scientists and Beirut residents. For a day, the world had watched and replayed this same footage of the city being consumed by a billowing, mile-high mushroom cloud.

Two years had passed since the interview. I had a different phone now and no direct way of reaching Khalid, let alone Abu Isa, but as I read about the disaster, I couldn’t help but wonder. Were either of the two men out on the water at the moment of the explosion? Were they anywhere near the port? I opened Google Maps and was able to find their tiny, unmarked marina in Ras Beirut, which was fortunately at enough of a distance from the port to have escaped ground zero status. Still, nowhere in Beirut was unscathed, and anyone on the water at the time of the blast was most likely in bad shape given how much of the impact the sea had absorbed.

I replayed Abu Isa’s words over and over in my head. Human beings first… we have to become human beings first. There is no use of talking about the environment until we become human beings. Had Abu Isa internalized a western, Orientalist view of Arabs as fierce savages unable to govern themselves? Or was he referring to the impasse of sectarianism, to the need for a new political imaginary in the Arab world, one that sees our common humanity as an organizing principle, that treats personhood as a trait superseding sect, tribe, or clan? I closed my laptop and stared out at a different sea in a different part of the globe.

It feels difficult to put into words why my conversation with Abu Isa and Khalid resonated the most with me, even as the engineers, scientists, and activists I spoke with provided much more detailed information about the nuts and bolts of the garbage crisis. But the two fishermen captured the essence of something deeper still, the crux of a national debate about what could produce such an astonishing systemic failure. That debate goes to the very root of the Lebanese political order itself and raises a difficult causation question: what prevents this system from functioning properly in even the most elementary ways?

A garbage crisis is, first and foremost, a problem of public infrastructure. The question is therefore primarily internal to Lebanon and Lebanese society, not a matter requiring a complex assessment of international political alliances or material links with other nations. There were no warplanes flying over Lebanon in the summer of 2015, no foreign powers meddling or threatening to invade. The polarizing talking points that might have been relevant during an Israeli invasion or a conflict with Syria were of no use here, and Lebanese people, for a brief time at least, saw no merit to any sectarian arguments made by their local leaders. What was needed, plain and simple, was an effective way to get rid of the trash.

If the garbage crisis served a positive function at all, it was to create space for solidarity where there is ordinarily none by giving people a common social problem to which they all concur that a divided government needed to find a solution. It is for this reason that Lebanon’s garbage protests in 2015 allowed a social movement to bridge sectarian divides for the first time since the country’s civil war, and why last year’s short-lived revolution could continue in that same vein. Beirut activists all agreed that while Lebanese people simply will not unite over international crises or foreign policy, at bare minimum, everyone can agree that something needs to be done about the stinking pile of refuse in front of their apartment building.

Just last week in Beirut, heaps of trash began appearing again at intersections and in vacant lots. The city can go weeks, even months, with minimal accumulation, but at the first sign of an unusually tall pile of refuse, people will start poking their heads out of apartment windows and frowning down from their balconies. Oh God, again? Why haven’t the trucks come around yet this week? Have you seen anything on the news? Rarely will the block get any satisfying answers, and nine times out of ten, the garbage is eventually removed. But the gossip is enough to keep the entire neighborhood on its toes. In Lebanon, trash can only mean trouble, and a lot of trash can only mean… better to shut the window before you find out.

1 The Druze are an Arabic-speaking esoteric ethnoreligious group who form one of Lebanon’s official 18 sectarian communities.

The Hypocrite Reader is free, but we publish some of the most fascinating writing on the internet. Our editors are volunteers and, until recently, so were our writers. During the 2020 coronavirus pandemic, we decided we needed to find a way to pay contributors for their work.

Help us pay writers (and our server bills) so we can keep this stuff coming. At that link, you can become a recurring backer on Patreon, where we offer thrilling rewards to our supporters. If you can't swing a monthly donation, you can also make a 1-time donation through our Ko-fi; even a few dollars helps!

The Hypocrite Reader operates without any kind of institutional support, and for the foreseeable future we plan to keep it that way. Your contributions are the only way we are able to keep doing what we do!

And if you'd like to read more of our useful, unexpected content, you can join our mailing list so that you'll hear from us when we publish.