The Editors

Introduction

ISSUE 95 | SYMPTOMS | JUL 2020

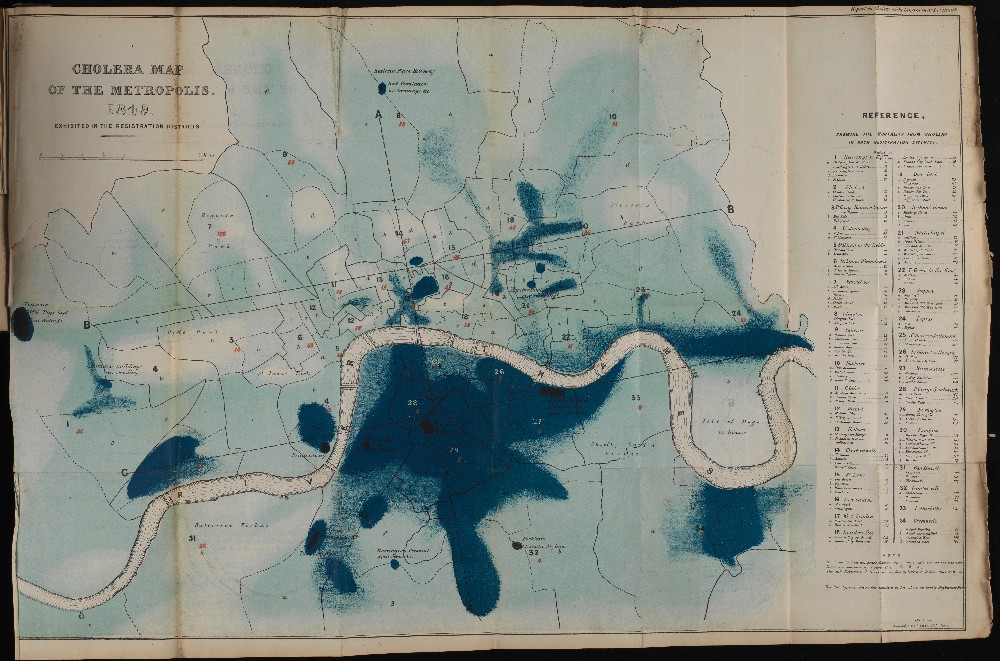

Several times since quarantine began, I have caught myself going down a Wikipedia rabbithole of reading articles on random Siberian towns, zooming in close on pictures of their streets and railway stations in a silly kind of ersatz travel. Or else I’ve found myself scrolling through virtual museum galleries in pale imitation of a physical trip. As a grad student, I often visited the Wellcome Collection, a medical museum in central London founded by a Victorian pharmaceutical mogul. I remember a shudder-inducing wall of gape-jawed obstetrical forceps; an array of votive clay viscera offered up by Romans seeking relief from gastric ailments; a Qing dynasty sign for a dentist’s office hung with long dangling strings of human teeth, proof of services rendered. Now, clicking distractedly through the museum’s online catalogue, I am drawn to its collection of 19th-century cholera studies. There’s a chart that presents the disease’s yearly mortality as a series of gobstopper-like colorful circles. There’s a map of London overlaid with cholera deaths rendered in such a gorgeous shade of blue that it’s difficult to register the emotional impact of what it signifies. There’s a spiraling graph of incidence by month entitled the Madras Cholera Clock, whose name seems to imply that illness is its own temporality. Artifacts like these used to seem quaint to me; now I stare at them with a new kind of urgency, as if they contained some secret power for explaining the present.

And goodness knows it needs illumination. In the last six months it’s become commonplace to say not only that the apocalypse is coming but that it is already here. Prepper sites are booming, and we’ve all been reading a nonstop stream of news that our healthcare system lacks capacity, that our rulers are murderous swindlers, and most bone-chilling of all, that there may be fundamental medical obstacles to finding a cure or developing a vaccine. This ambient foreshortening of the future makes it easy to focus on a feeling of dread or despair. But the George Floyd Uprisings, an astonishing flowering of Black resistance in the U.S. and worldwide, have made it hard to buy the idea of the end of the world. We find it more likely that we are at a moment of change—don’t the poets tell us that nothing really dies?—and no one knows which way is up in the vertiginous spin of it. So the battle will be fought in the place where limited understanding meets the willingness to see what happens. One of our former editors, Michael Kinnucan, gave a definition for this middle ground that included the following two points: “a time horizon of 5-10 years which neither accepts the insistence of the immediate present nor projects solutions into an unknowable future” and “a war of position which attempts to build organizational resources that will be useful in all circumstances rather than to plot out specific projects that depend on circumstances we can’t know.”

Seeing what happens is a kind of trust work—it’s not an attempt to make history conform to our preconceived notions, but it is experimental, not passive. Taking as her starting point her own tic disorder, Sandow Sinai writes that rather than overcoming the contradictions between mind and body, desire and execution, we need to observe those contradictions as they happen so that we can recognize the problems that give rise to them and achieve mutual recognition with those who may struggle along with us. To do that, we need to be willing to glean truth where we can find it. Honesty is key: the truth may not set us free, but we have to trust it, because nothing else will. As you work (as we hope you are working) to do what you can in this war of position, we hope you’ll find something useful and unexpected to glean from the pages of the Hypocrite Reader––a feeling, a startled laugh, an old idea, or a new one. It is always better to go sideways than to beat your head against a wall.

It is our hope that the articles of SYMPTOMS will serve as hints to some diagonal dance steps. In a dispatch from a New Mexico emergency room in the early days of the pandemic, Olivia Durif suggests that our narrow definition of “emergency” hides the structural violence in which so much illness is rooted. Political bodies are also subject of Marybeth Ruether-Wu’s essay, which examines how medieval notions of disease influenced and intersected with contemporary understandings of state corruption––a deep dive into humoral medicine with surprising relevance to current discussions of justice. The British Empire’s fear of epidemics in its colonies was part of a broader view that “posited the eradication of disease in the tropics and the civilizing mission as coterminous,” writes Tamara Fernando––but that fear also served as a background against which exploited workers could leverage illness as a mode of resistance. And Alexander Wells traces the history of fatigue, looking at how European societies have articulated a “disdain for the exhausted” and how exhaustion itself might serve as a means of expressing dissent.

Nastya Panichkina reports on joining an online community of Russian women whose alternative fertility regimens develop a spiritual valence. And in her long-scroll comic about her treatment for breast cancer, Hannah Blair describes a medical establishment that blithely urges women patients to pursue plastic surgery and “positive thinking.”

“Internal organs—now that’s a legacy of Stalinism, of course,” writes Sergei Sokolovsky in a new translation from the Russian by Ainsley Morse. Sokolovsky’s micro-stories are set in a continuous present that’s stitched together from misplaced scraps of history.

Writing at a moment when “the volume knob [has been] turned up on history,” Katy Burnett finds herself returning to Alexander Kluge’s fictionalized account of the day Hitler shot himself, observing eerie resonances between Kluge’s account of a state’s failure and the situation currently facing the United States. “Until we reach the postscript,” she writes, “time repeats or gets stuck, like a skipping record.” She’s talking about Kluge’s novel, but it’s a phrase that could just as easily be referring to reality, where every day we watch cycles of case numbers rising and falling, street uprisings and their violent suppression. At some future point, a better world; between now and then, we must continue to struggle in the middle ground, with no certainty of what survival will look like––let alone victory. “Who keeps us safe?” the protesters chant. “We keep us safe!” Finding the strength to do this, Katy writes, “requires the imagination and solidarity of everybody who’s left.”

Yours in hypocrisy,

Erica, Cat, Piper, Kit, and Sam