James Rumsey-Merlan

Microaggress!

ISSUE 70 | SAFE | DEC 2016

I grew up in Australia, a society still grappling with its genocidal past. To make a broad-brush statement about racism in Australia, you might say that it is equal in quantity to what you found and find in the US, even if it is of a slightly different quality. One of the best-loved pub ballads in Australia is “Tie Me Kangaroo Down, Sport.” In it, a dying stockman sings his will and testament. It includes a verse about emancipating his Aboriginal “employees”:

Let me Abos go loose, LouThe song was written by Rolf Harris in the 1960s, but I remember it being played in its uncensored entirety in pubs in the Northern Territory when I was a kid in the 90s. “Abo” is a word heavy with hatred, shorthand for people who were treated as chattel by Australia’s white colonisers. One state over from the Northern Territory, Queensland was governed until 1987 by a man named Joh Bjelke-Petersen, who fought tooth and nail to keep signs posted in public parks that read, “No Dogs or Aborigines.” Partly as a way of stifling dissent, he kept a law on the books that prohibited three or more Aboriginal people from congregating in the same place, although enforcement of the law was, mercifully, patchy. To make a long story short: expressing overtly racist sentiments was more broadly palatable until more recently in Australia than in the US.

Let me Abos go loose:

They're of no further use, Lou

So let me Abos go loose.

Though quite different in some respects, Australia is very much in the linguistic and cultural slipstream of the US. I remember learning the imported rhyme “Eeny-meeny miney mo, catch a tiger by the toe,” when I was in primary school. One day, my mother heard me repeat the rhyme at home. She got furious and told me never to say what I had just said again. “Why?” I asked. She obviously thought about dodging the question and then said, “because the word ‘tiger’ in that rhyme was not ‘tiger’ when I was growing up. It was ‘nigger.’” She went on to explain to me at some length, but in terms comprehensible to an eight year-old, what the despicable history of that word was. I don’t remember if I apologised to her, but I do remember that I wanted to. I was overcome with a feeling that I had done something awful to other people, which was especially difficult for me to stomach since I had always imagined myself to be a sensitive kid, able to intuit what I could say to please or hurt the adults and other kids around me. This time I had hurt my mother and many other people far away, without even intending to.

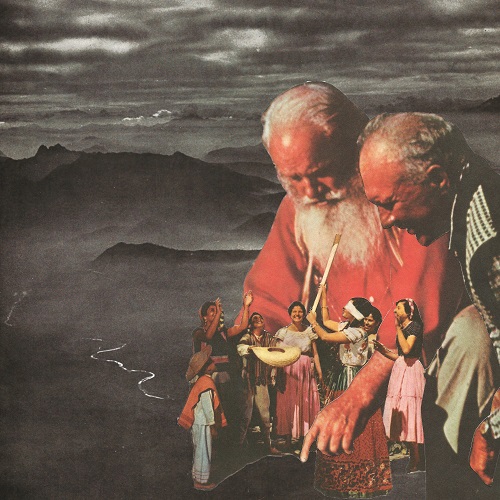

Illustration by Fontaine Capel

We didn’t watch golf, except when my godfather was staying with us. He was a wonderful man, a product of the free-wheeling left-anarchist currents that sloshed through certain Sydney pubs in the 1960s. He retired early from life as a professor of anthropology at the university, mostly so that he could play golf half of the year in London and half of the year at Royal Canberra, which he thought was the best course in the world when the weather was good. He turned on the TV to watch the golf one afternoon, and I noticed that Tiger Woods’ nose was flatter than mine. I think I am not misremembering when I say that I had been given a fear of the word “tiger” by what my mother had told me about its terrible, secret meaning a few years before. So I asked the living room at large, “Why is Mr. Woods’ nose flat?” My mother looked at me crossly and told me that I had watched enough TV for one day. She didn’t turn the TV off, because my godfather was there and wanted to watch, but she did shoo me out of the room, my question unanswered. Later, when I was in my bedroom by myself she came to me and said, “Tiger Woods has a flatter nose than you because he is part Thai and part African-American and you aren’t. But no-one is really excited about that. He is famous for his golfing, not for his nose.” She walked out of my room and I was left to ponder this. I had never known her to be excited about anyone’s golfing. And of course this man was on TV because of his golfing, but why did that make it shameful to ask about his nose? I couldn’t quite work it out, but it did make me absolutely dead-set against mentioning tigers or anything to do with them in my mother’s presence again.

When I was twelve, my parents took us to Bavaria for a year. I was just old enough to go to the local Gymnasium, where I had no trouble making friends. The first week I was there, Robert Geiger invited me over to his house on the weekend. He had red hair and the name Geiger made me ever-so-slightly nauseous, either because it made me think of radiation, precocious kid that I was, or because it reminded me of the name of the unspeakable feline. Maybe it was both. Maybe it was neither and I have just come to remember tigers as the totems of my education in bigotry. He lived in a big house and his mother was very friendly. She had blond hair and she made us Käsespätzle for lunch. I didn’t understand much German at that point, let alone Bavarian, which is what Robert spoke with his mother. After lunch, Robert and I went for a walk. His house was at the edge of town and we started down the bike-path that led to the next village. For some reason, when he talked I understood almost everything. Once we were all the way out in the countryside he asked me a question. “Have you met any Turks?” “No,” I said, answering as honestly as I could, although I was not altogether sure what a Turk looked like. “If you meet one,” he said, “you can tell me and we can have him beaten up.” Zsamschlogen was the word he used for "beat up", and I was quite proud of myself for understanding it. “OK,” I said, unsure of why such drastic action would be necessary.

A few years later I was riding in the car with my mother and something clicked. “Mum, do you realise that my friend Robert Geiger in Weilheim was a neo-Nazi?” As soon as I said the word, I realised it wasn’t quite the right one. Probably it was overstating things to say that Robert was any sort of Nazi, just a garden-variety xenophobe. But my mother didn’t miss a beat. “Not just him,” she said, “his mother too. Every time I went to pick you up she said that she liked me because I was the right kind of immigrant. I told her we weren’t going to stay, that we weren’t immigrants, but she just thought that I was being polite.” I thought about this. My mother, who had scolded me for my confusions about tigers, who shouted at the evening news when the chief minister of the Northern Territory came on and said that Aboriginal people needed to have a good, hard look in the mirror before they started saying that his government was to blame for Aboriginal deaths in custody—she had knowingly let me consort with a carrot-topped Bavarian imp in a fairly-advanced state of Nazism, or at least nastiness.

I asked her why she let me play with the Nazi. “Because I wanted to get you out of my hair for a few hours.” She chuckled to herself. “OK, not just that. I thought it would be better for you to work out what’s wrong with being a Nazi by yourself.” My mother is an odd soul, but there might be something to what she said that day in the car. The current discussion of micro-aggressions presupposes that we all know what they are. Or at least that we can be given an exhaustive list of them in the first week of college, memorise it, and never violate it. But how was I to know that my recitation of “eeny meeny” would be a micro-aggression against my mother (and, by proxy, against a group of people on the other side of the Pacific, a group of people twice as big as the population of Australia)? It also bears saying that according to the contemporary understanding of “micro-aggression”, my recitation of “eeny meeny” might not have been one at all. My mother isn’t African-American, just a righteous white lady on a far-flung island. Is her sense of offence less heartfelt than that of an African-American mother in Cleveland who overhears the rhyme as she waits by the school-gates for her kid to get off school? Maybe so, but what I remember (and what taught me what I needed to learn) is my mother explaining the thing to me, angry as a cut snake.

To put it another way: one problem with the contemporary understanding of the “micro-aggression” is the parochialism it assumes in its audience. Is it less bad to say that Australians are a gaggle of drunken convicts if there are no Australians present? This will be allowed to pass as a light example, perhaps because Australians are often erroneously assumed to be white and privileged one and all—but it is certainly already the kind of thing that would be taken as a micro-aggression in the contemporary university. Yes, according to the new dispensation, which says that what is salient is the quantum of offence produced. If no Australians are present to hear the remark, no offence is given. This is nonsense as the basis for the formulation of an ethical principle. Moreover, I can assure you that it is much more interesting to impute drunkenness to the Australian while she is still present. She might get offended, or she might buy you a drink or she might do both. But the decision is hers, not that of some all-knowing bartender in the sky. Be assured, also, that it is by talking to Nazis that your children will learn not to be Nazis. The road to a worthwhile categorical standard for offence goes through talk, saying things that other people, some of them mothers, will take apart and correct, sooner or later. Joh Bjelke-Petersen, the premier of Queensland, thought that the ticket to political harmony was stopping people from congregating to talk openly and without euphemism about injustice or, indeed, anything else. Let’s not fall for that one again.

Addendum: I wrote this piece, sent it out to a few friends and found that their criticisms were all similar: say more about the political lessons to be gleaned from these anecdotes. But I intended them to be anecdotes, not political lessons. A personal politics is a higgledy-piggledy collection of passions, pieties and the very few explicit political lessons that you remember your mother giving you. Perhaps it is an obvious corollary of the Family Romance that a child never gets its politics from its father. Maybe that is all I really wanted to say. But OK, I will throw out a reference to Isaiah Berlin. Berlin saw two types of freedom in the world, the freedom that citizens had in America and the freedom that they had in Europe. Free Europeans were the beneficiaries of what he called “positive freedom.” The northern European state (whichever one, but Germany is the biggest, most obvious example) does things to help its citizens achieve “freedom,” without actively trying to specify the content of that complete and vertiginous freedom, the complete and vertiginous freedom that made a northern European such as Kierkegaard so nervous. The state pays for child-care, pays for health care, pays for the continuing survival of the unemployed. If you are able to take your mind off those things, you will have more time to think of other things; how you will choose to exercise your freedom, how you will repay the state for its goodness, etc. Freedom in America has, Berlin argues, historically been of another kind, which he called “negative.” Americans have been free not to be interfered with by their government, or their fellow Americans. The state monopolises violence and you do the rest. An even more vertiginous freedom. This binary conception of freedom seems inexact, even caricatured. Massive state intervention in the private fortunes of citizens was enacted in the US long before the late 1940s, when the Attlee government created the National Health Service in Britain, which is a sort of talisman for Britishers who imagine that they have a competent, interventionist state. The New Deal was only a local point of inflection in a long history of US nanny-statism. In 1807, Thomas Jefferson banned the importation of slaves into the United States. By enacting a total tariff, he hoped to drive up the prices paid for slaves, of which his fellow Virginians had an oversupply. The idea that commerce should be free of government intervention would certainly have come as a surprise to Virginia’s favourite son.

But this is beside the point. The point is that the US thinks of itself as a nation negatively free. Americans often seem to entertain certain pieties about the national myth that they also seek to realise in their own lives. They imagine that to be free is to be unmolested, and it is this that the poor and the marginalised often aspire to, those people who are by definition molested by the conditions of everyday life, by want, by competition among the many for scarce, high-fructose corn-syrup soaked resources. They aspire to the unmolested lives that you might easily imagine the privileged, who tend to be white, already lead. Smooth, suburban lives.

To some extent the privileged do lead these lives, I imagine. Such historically white institutions as the US congress have long been a model of quiet decorum, compared to the parliament of Britain, which is almost comically rambunctious. Such historically white institutions as the major newspapers of this country, say the New York Times and the Washington Post, have always been less inclined to argue with each other than the newspapers read by white people in France which go from Libération to Le Figaro, from much farther left than the New York Times to about as far right as the Wall Street Journal. Distaste for discord is as old and as white as Puritanism itself. But there is another strand in elite American political and private life that is every bit as disputatious as the Prime Minister’s Questions. The Lincoln-Douglas debate, the Nixon-Kennedy debate, the shouting protestors on both sides of gates of integrating schools in the 1960s, Tupac and Biggie, Kanye and Taylor Swift. The negative freedom for the elite not to be shouted at is as much of a historical fiction as the freedom of American merchants not to be interfered with by the state. The oppressive and prescriptive freedom of the Puritans was only one of many that jostled for position in the Massachusetts Bay Colony. The colony of Merrymount rejected the narrow limits on expressible thought that applied if you were one of the Puritans up the road. In 1627 the colonists of Merrymount celebrated Mayday by dancing around a pole with the local Indians. Shortly thereafter they were overrun and punished by the local band of Puritans for their heterodox form of interaction with the natives, heterodox because it didn’t involve killing or converting them. Censorship has a long and proud history in this country, but so does carnival. We should recognise that, and recognise that the freedom to be carnivalesque can be a positive one, one that involves real interchange and exchange, the bases for empathetic politics.