Michael Kinnucan

Man-Making

ISSUE 57 | CRYING WOLF | OCT 2015

1

H.G. Wells’s 1896 sci-fi novel The Island of Doctor Moreau contains what is surely one of the great mad-scientist soliloquies in world literature. A sampling:

“But,” said I, “I still do not understand. Where is your justification for inflicting all this pain? The only thing that could excuse vivisection to me would be some application—”“Precisely,” said he. “But, you see, I am differently constituted. We are on different platforms. You are a materialist.”

“I am not a materialist,” I began hotly.

“In my view—in my view. For it is just this question of pain that parts us. So long as visible or audible pain turns you sick; so long as your own pains drive you; so long as pain underlies your propositions about sin,—so long, I tell you, you are an animal, thinking a little less obscurely what an animal feels. This pain—”

I gave an impatient shrug at such sophistry.

“Oh, but it is such a little thing! A mind truly opened to what science has to teach must see that it is a little thing. It may be that save in this little planet, this speck of cosmic dust, invisible long before the nearest star could be attained—it may be, I say, that nowhere else does this thing called pain occur. But the laws we feel our way towards—Why, even on this earth, even among living things, what pain is there?”

As he spoke he drew a little penknife from his pocket, opened the smaller blade, and moved his chair so that I could see his thigh. Then, choosing the place deliberately, he drove the blade into his leg and withdrew it.

The narrator is a prim teetotaling Brit named Prendick who gets shipwrecked and washes up on an island inhabited by two secretive men of science, the mysterious Doctor Moreau and his sad drunk of an assistant, Montgomery. The island also contains a number of dark, eerie, strange-looking people who babble incomprehensibly—“natives,” he figures, naturally, being a Victorian Englishman. Then he realizes that one of them has the ears of a dog.

Suddenly it all clicks for him, or seems to: he remembers hearing of a brilliant vivisectionist by the name of Moreau who disappeared from London after an obscure scandal ten years ago. This is the same man—and he’s using his uncanny talents to turn men into beasts! Moreau makes a run for it and falls in with the beast-man-creatures, who chant their law at him:

Not to go on all-fours; that is the Law. Are we not Men?

Not to suck up Drink; that is the Law. Are we not Men?

Not to eat Fish or Flesh; that is the Law. Are we not Men?

Not to claw the Bark of Trees; that is the Law. Are we not Men?

Not to chase other Men; that is the Law. Are we not Men?”

But Doctor Moreau catches up with him and explains that he’s got it all wrong: he’s not turning men into beasts, but beasts into men. (What sorts of beasts? All sorts! Bulls, bears, hyenas, pigs, a St. Bernard. Sometimes he mixes two beasts together, to produce for instance bull-bear-men.)

When he is at length satisfied that he’s not under the knife, Prendick calms down and asks the natural question: why in God’s name would Moreau do this? The answer:

“These creatures you have seen are animals carven and wrought into new shapes. To that, to the study of the plasticity of living forms, my life has been devoted. I have studied for years, gaining in knowledge as I go. I see you look horrified, and yet I am telling you nothing new…”

Very much indeed of what we call moral education, he said, is such an artificial modification and perversion of instinct; pugnacity is trained into courageous self-sacrifice, and suppressed sexuality into religious emotion. And the great difference between man and monkey is in the larynx, he continued,—in the incapacity to frame delicately different sound-symbols by which thought could be sustained. In this I failed to agree with him, but with a certain incivility he declined to notice my objection. He repeated that the thing was so, and continued his account of his work.

Why test the plasticity-theory using the human form, Prendick asks?

He confessed that he had chosen that form by chance. “I might just as well have worked to form sheep into llamas and llamas into sheep.”

2

A large chunk of Moreau’s soliloquy is taken verbatim from a pop-science article Wells had published a year earlier in the Saturday Review on the limits of the eugenic imagination. The article opens as follows:

The generalization of heredity may be pushed to extremes, to an almost fanatical fatalism. There are excellent people who have elevated systematic breeding into a creed, and adorned it with a propaganda. The hereditary tendency plays, in modern romance, the part of the malignant fairy, and its victims drive through life blighted from the very beginning. It often seems to be tacitly assumed that a living thing is at the utmost nothing more than the complete realization of its birth possibilities, and so heredity becomes confused with theological predestination. But, after all, the birth tendencies are only one set of factors in the making of the living creature. We overlook only too often the fact that a living being may also be regarded as raw material, as something plastic, something that may be shaped and altered, that this, possibly, may be added and that eliminated, and the organism as a whole developed far beyond its apparent possibilities. We overlook this collateral factor, and so too much of our modern morality becomes mere subservience to natural selection, and we find it not only the discreetest but the wisest course to drive before the wind.

The modern reader of this paragraph may expect Wells to go on to vaunt the possibilities of nurture over nature and criticize eugenicists for going to extremes in their biological determinism. Not at all. Instead we get a menagerie of surgical horrors from throughout history—torments of the Inquisition, virtuoso feats of vivisection, carnival freaks said to have been mangled just to be shown. We are offered the delightful possibility that scientists may someday succeed in “taking living creatures and moulding them into the most amazing forms; it may be, even reviving the monsters of mythology, realizing the fantasies of the taxidermist, his mermaids and what-not, in flesh and blood.” He adds almost as an afterthought that such transformations need not be limited to the physical: what is morality, after all, but the training of, for instance, stupid pugnacity into noble courage, and suppressed sexual urges into religious zeal? All this reappears in Moreau’s monologue a year later.

3

Wells himself was, like nearly every other Victorian you’ve ever heard of, a supporter of eugenics. He was also perhaps the most prominent socialist in England, and, like many other 19th century socialists, saw no contradiction whatsoever between the two. Wells’s family had sunk from hard up to dirt poor over the course of his childhood, he had survived abusive apprenticeship and got his education as a half-starved scholarship kid, and his socialism was borne of observation from below; he saw a society which had devoted its immense and rapidly increasing technological powers to producing baubles for the rich and arming itself to the teeth while the working classes scraped by on table scraps. He predicted the atomic bomb, the tank, and a global war beginning in 1940; as he wrote in a preface to the 1941 edition of his prescient 1907 novel The War in the Air, his epitaph should read: “I told you so. You damned fools.”

So, although blessed with a broad streak of technophilic optimism, Wells never lost sight of the threats facing a society whose scientific and technological progress outstripped by an ever widening margin its moral improvement. Humans now possessed the capacity to build Utopia, and the power to destroy themselves; the moment of decision seemed to get closer every year. The question of how to rationalize politics and morals, how to remake humanity into something capable of wielding such technical power for good, was urgent.

Hence eugenics: one among many ways to apply the latest in scientific rationality to the civilizing of mankind, together with world government and progressive pedagogy. Now that Darwin had plumbed the secret depths of heredity, how could we leave such a vital matter to chance and blind lust?

4

There can’t be many ideas in the past century that have gone from uncontroversial to unspeakable as thoroughly and quickly as eugenics, and it’s not easy to see exactly why it happened. If Foucault is right (and you know he is) that modern states govern biopolitically, understanding their subjects as populations of living beings and acting to promote this life, why is the idea that they should intervene in the gene pool, once a virtual elite consensus, so thoroughly dead?

I believe the conventional view is that eugenics was discredited by the Nazis; would that they had discredited war and nationalism too. I would suggest instead that, like so many other technologies of governance before it, it was simply rendered obsolete. Eugenics was always sort of an impractical-utopian idea, after all: It’s all very well to sterilize some institutionalized populations, but anything more thoroughgoing would require a vast infrastructure of control over mating and reproduction and provoke considerable resistance. The modern welfare state which emerged from the ashes of World War II regarded surplus population as a problem of economic management, and the mass availability of birth control effectively “economized” reproduction: instead of state-centralized breeding, women would now be incentivized to use the means of reproduction as best they could. And with the advent of income support programs, the poor started looking a lot less like shrunken biological degenerates—it turned out they’d just been hungry all the time.

Eugenics is outmoded, so it’s not coming back; the next time technological intervention to improve the results of human reproduction becomes a political issue, it will take a different form. (It’ll be designer babies, just saying. Already most fetuses with Downs Syndrome are aborted, and we’ll go from there. Not state-powered eugenics but the open market in genes, as competitive as pre-school applications on the Upper East Side.) What has not gone away—what never does, really—is the problem Plato isolated in his proto-sci-fi classic The Republic: the political-technological problem of how to produce governable human beings.

5

This political question is the primary subject of sci-fi: not technology but the reaction of technology on the humans who wield it. Or, not material technology but the technology of political power. For this reason sci-fi recurs again and again to the question of the technological production of man: the vanishing point where the production of tools and that of societies become indistinguishable, and of course theological.

Sci-fi myths of man-making may be divided into two categories according to the motivations of the creators. In the first, the creator sets out to make intelligent tools, or artificial slaves—robots designed to serve and designed with the intelligence to serve perfectly. This may be called the “robot” tradition, and descends from Karel Čapek’s play Rossum’s Universal Robots, which introduced the term (from the Czech for the labor required of serfs) into English. Asimov’s robot books, Dick’s Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?, its adaptation in Blade Runner, Terminator, and The Matrix all belong here. The bad thing about being a robot is that you’re a slave, but the bright side is that you’re saved from existential questions about why you’re here: you’re here to serve the master-race. Faced with this simple situation, most robots follow the example of Čapek’s originals, overthrow the master-race and turn us humans into corpses or slaves or living batteries. Whether this decision appears justifiable is a good index of where the author’s political sympathies lie. (I’m always on #teamrobot.)

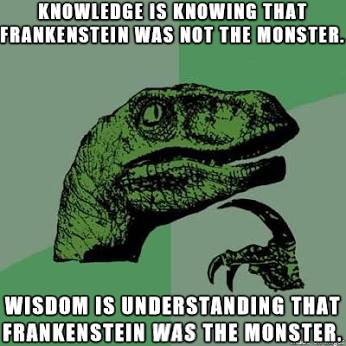

In the second category, humans create humans out of some other, more obscure motive—scientific curiosity, pride, God-envy. These creatures are not robots but monsters. Frankenstein, the first sci-fi novel, is the classic example here. Frankenstein’s monster gets to roam free all over the world, learn to read by eavesdropping, etc.; he’s not a slave. But he’s got a bigger problem: he doesn’t know why Doctor Frankenstein brought him into the world, and he has to chase the doctor around to find out.

This of course merely places him in the human condition: we too were brought into being for non-obvious reasons and feel the need to chase our Maker down and demand some answers. It seems almost too obvious to point out that Frankenstein’s monster is in the same relation to Frankenstein as man is to God. But what is the substance of that relation? While the robot is a tool, which is to say, a being whose end is given from outside, the monster is an experiment, an attempt at discovery; for his maker and therefore for the monster himself, his existence juts out into the unknown. He is a creature in the religious sense, and stories about him are always essays in theodicy or its opposite, speculations on what motivates God.

6

But the theological interpretation of man-making stories isn’t the last word by any means. The pleasure and horror of these stories is that man appears on both sides of the creation-relation—the brilliant scientist who dares too much and his suffering creation are two faces of the human: homo culturans and homo culturata. Doctor Frankenstein, like his monster, is driven on by a question he can’t let go of; his monster is his will to know embodied. And the monster in turn is consumed by a guilt he can’t escape.

The best parts of The Matrix are the ones that milk this double image for its comic value: Neo in the office, getting yelled at by his boss for not adding value while in reality he’s producing electricity for the robot dystopia, or Agent Smith’s monologue about how much the simulated human world disgusts him: “This zoo… this smell, if there is such a thing… I must get free.” Humans created robots as tools and were entrapped by them; now the robots in turn are using humans as tools, and are similarly trapped. Each encounters the world of its own making with a sense of revulsion.

The modern myths of man-making are not so much theological parables as materialist accountings for theology. Man is double, creator and created, victim and criminal; God is a projection meant to explain or escape this contradiction. Doctor Frankenstein is not a metaphor for God but a reading of God as metaphor: our own insatiability, cruelty, pride and irresponsibility doom us to things that we then blame God for.

Frankenstein and its affiliate myths return theological problems to their human source, but do not resolve them: the double and contradictory figure of man remains, and creator-scientist and created-monster, though they may exchange places, remain locked in contradiction. The robots overthrow their masters only to enslave them, Frankenstein’s monster murders but cannot forgive. The politics of man-making sci-fi is that of Feuerbach’s undialectical materialism as Marx describes it:

The materialist doctrine concerning the changing of circumstances and upbringing forgets that circumstances are changed by men and that it is essential to educate the educator himself. This doctrine must, therefore, divide society into two parts, one of which is superior to society.

7

The Island of Doctor Moreau is, like Frankenstein, a monster story. The beast-men on the island are experiments, and indeed, as Moreau explains, failed ones: no matter how much he vivisects their glands and larynxes and so forth, they never stay “human”: slowly but surely they turn back into beasts. As each experiment he fails, he simply releases it to roam the island; and so the failed men have gradually formed a little village of their own, with a religion revolving around Moreau.

His is the House of Pain.

His is the Hand that makes.

His is the Hand that wounds.

His is the Hand that heals.

His is the lightning flash.

His is the deep, salt sea.

Significantly, this religion is not Moreau’s invention—it’s a co-creation of Montgomery, who wants to keep the beastmen tame, and the beasts themselves, attempting to interpret their all-too-vivid memory of vivisection. Moreau has no time for his half-wrought things, which only remind him of past failure; he simply mops up the blood from his last victim and moves on to the next. He is obsessed with his work.

But not long after Prendick arrives the beasts begin to grow restless, to “degenerate.” Their degeneration takes two apparently contradictory forms: animal instinct and a very human kind of doubt. They long to run on all fours and hunt prey, but at the same time the craftier of them begin to suspect that their human masters are not as powerful and invulnerable as they had thought, that the whole “House of Pain” / “Are we not men?” edifice is a tissue of lies.

Then everything snaps. One of the beastmen gets loose and kills Moreau, Montgomery goes mad and dies too, and for a moment it seems that Prendick, now alone among the beastmen who have understood that humans are as mortal as they themselves, will meet the same fate.

But prim, teetotaling Prendick turns out to be a gifted theologian and liar. He blocks the beasts’ intellectual liberation and slows their descent into brutality by convincing them that Moreau has not died, that he has merely changed forms: he is in the sky now, watching over them, all-knowing and all-punishing. And so Moreau manages to live in relative safety among them for months, until at last a boat washes ashore and he can set off home.

Wells belabors the point in an epilogue: although Prendick manages to get back to London, he is forever marked by his experience, because he no longer sees his fellow men the same way. He senses in them something animal, revolting, half-formed, half-tamed. He withdraws from the business of life and can find comfort only at his telescope, peering up at the stars.

8

Again the doubled image: man is Moreau, the technologist, the shaper, and man is also his victim-subjects, the tortured, the shaped. What drives Moreau to his assault on the “limits of individual plasticity”? Why attempt to make human beings out of animals, when there are too many humans as it is? After accusing Prendick of being a materialist, he goes on:

“Then I am a religious man, Prendick, as every sane man must be. It may be, I fancy, that I have seen more of the ways of this world's Maker than you,—for I have sought his laws, in my way, all my life, while you, I understand, have been collecting butterflies. And I tell you, pleasure and pain have nothing to do with heaven or hell. Pleasure and pain—bah! What is your theologian's ecstasy but Mahomet's houri in the dark? This store which men and women set on pleasure and pain, Prendick, is the mark of the beast upon them,—the mark of the beast from which they came! Pain, pain and pleasure, they are for us only so long as we wriggle in the dust.

Moreau takes human beings as a model, and yet he sees in other humans the beasts from which they came: they too are a failed experiment, or failed so far. One wonders what would satisfy him—if he managed to create beastman who stayed human, wouldn’t it be just as much of a worm as the human beings it was modeled after? Moreau strives to create a perfect image of an imperfect thing; as he himself says, he may as well be turning llamas into sheep.

On Moreau’s island, civilization and morality are as cruel as vivisection, and as futile: not only does the beast remain within, but there seems little point in eradicating it, no ideal worth so much suffering. It’s easy to see why Prendick was traumatized by his experience: he saw through the religion he was preaching, he kept using it, cynically, for convenience, but behind this lie he had nothing else—nothing but the animal will to survive.

If there is a “true” human in The Island of Doctor Moreau it is of course Moreau himself, driven by monomaniacal intellectual lust, willing to make every sacrifice and break every taboo in pursuit of his goal. And yet in a sense he finds himself in exactly the same situation as his creations: striving, pathetically, for the human form, failing again and again.

9

What does it mean that these man-making myths always end so terribly? It’s a chicken-and-egg conundrum, exactly what Marx pointed to: man makes society, society makes man. There’s no human good enough to create, and so no good enough human will ever be created; we are corrupt and so all our seed will be corrupted. Wells wrote a happier book once, A Modern Utopia, about the ideal rational society; when Joseph Conrad read it he wrote to Wells that it did not "take sufficient account of human imbecility which is cunning and perfidious." That sounds about right.

What to do? This I don’t know. At the limit, the striving after ideals—Utopianism in the Marxist sense—is obviously a non-starter. So you could listen to Marx, on Feuerbach:

The coincidence of the changing of circumstances and of human activity or self-changing can be conceived and rationally understood only as revolutionary practice.

Or to what may well be the only hopeful book in the man-making genre, Thus Spoke Zarathustra:

Man is a rope, tied between beast and superman—a rope over an abyss… What is great in man is that he is a bridge and not an end: what can be loved in man is that he is an overture and a going under. I love those who do not know how to live, except by going under, for they are those who cross over.