Sarah Mendelsohn

Serious Sun

ISSUE 52 | FUN GAMES | MAY 2015

When you do, your vision bruises. Those dark splotches: shadows? Blind spots, afterimages? After images, then what? After looking into the light, it’s hard to see anything clearly.

“Exposure.”

“Face your fears.” (Or face them repeatedly. “Exposure therapy.”)

“Seeing is believing,” or, “seeing is understanding—”

to be “taken somewhere” by a work of art,

to be “transported” anywhere,

to be “transported within” yourself.

To “walk” someone “through” a “memory.”

On a bright day in February I think of videos I watched last October. A few months after visiting the late Harun Farocki’s Serious Games exhibition at the Hamburger Bahnhof in Berlin, I decide to write about it from memory, without trying to find or watch the videos again. I try to write about it as something I’ve internalized. What impressed me, why are these videos still on my mind? How do they function in memory, and in relation to memory? Inspired to describe the afterimages instilled by Farocki’s videos, I start to question the role that visual memory plays in understanding the way I am affected by a work of art. These works penetrate and discharge descriptive language.

To see the world as if “through goggles.”

To be “blind to the world.”

“The visible world.”

“The moving image.”

Can virtual realities help people understand experience—either their own or someone else’s?

But actually, how can you not look?

The exhibition at the Hamburger Bahnhof included five videos and one digitized film, installed as projections on screens in a darkened gallery. The exhibition title Ernste Spiele (Serious Games) is also the title of a series of works Farocki made between 2009 and 2011, from which four video installations are featured here. Using footage from a U.S. military training facility in Twentynine Palms, California, the Serious Games videos explore the ways gaming and visualization software are used in the preparation of U.S. soldiers for deployment to Afghanistan and Iraq, as well as in the therapeutic treatment of trauma after soldiers return to the States. “Serious Games” is an industry term, referring to video or computer games intended for use other than entertainment, such as education, mourning, or a process of recovery. In each setting Farocki addresses the specific visual worlds depicted—and, in fact, created—by virtual simulation. How do the ways that these technologies are designed and used determine the designation of inner and outer worlds: for instructional purposes between an instructor and soldiers in training, or between a therapist and veteran in a therapy session? How are inner and outer worlds mediated, and can they, in fact, be bridged?

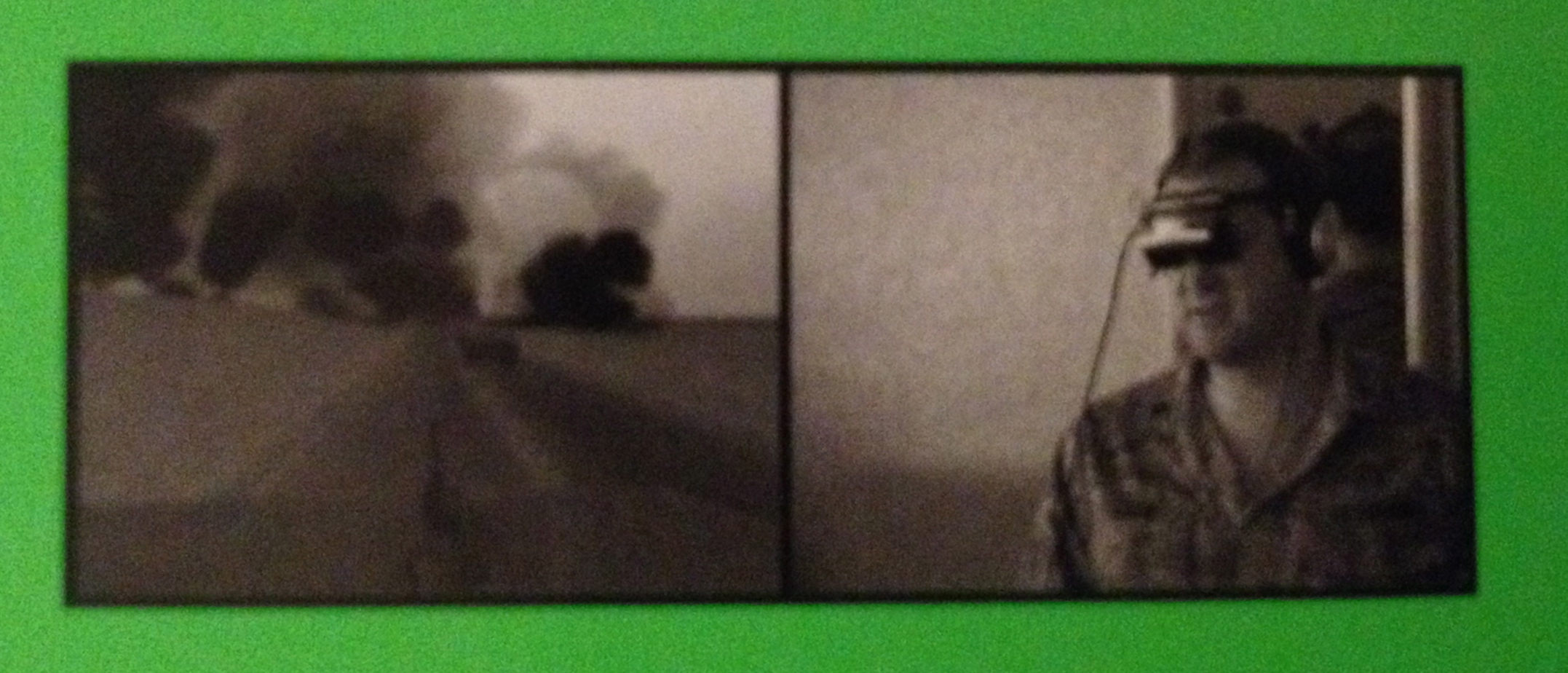

The relationships between internal and external are multiple. In the context of the therapy session, the focus of Serious Games III: Immersion (2009), video game images are used to illustrate experiences as they are remembered, while also helping to shape the process of remembering. A veteran wearing visualization goggles walks a therapist through the details of a reconnaissance mission trauma. The therapist sits at a computer, as the vet verbally narrates successive repetitions of the events leading to the death of another soldier. Farocki presents the therapy session as a two-channel video installation. On the right side of the screen is the veteran: male, probably in his thirties, white, receding hairline, digital-camo army fatigues, virtual-reality headset in place over his eyes. The viewer sees his effort at remembering the details of the events he describes: an early mission, the loss of a friend, and then, more viscerally, having to deal with his friend’s destroyed body. The veteran’s discomfort and pain are visible. Without showing very much of the room in which their session takes place, the camera cuts periodically to the therapist: female, white, middle-aged, long, dark curly hair, calm expression, glasses (maybe?). He definitely wears glasses, beneath the goggles. She coaches him, tells him he’s doing great, encourages him to keep going. Her eyes move back and forth, from her patient to her computer screen, from which she controls the visualization software and determines the images appearing in his goggles. On the left side of the screen those images appear, closely resembling popular video game graphics: a mostly empty city in a desert.

The animated images stand in for the veteran’s experience, his memory, his inner world. They are at once impressions and illustrations, incorporating elements from his narrative as visual information: details like location and atmospheric information, the time of day, the cloud coverage. Not told where exactly these events have taken place, the viewer is left to assume it is somewhere in the Middle East. The images create a schematic representation of his story. But these technologies also operate spatially and socially. The virtual-reality headset literally blocks the veteran’s vision of anything else happening in the room where his therapy session takes place, sealing him within himself. The images become a wall in front of his eyes, marking the boundary of his interiority, his remove from anyone who does not share his vision.

The viewer’s movement through the Middle Eastern cityscape is dreamy, disembodied: small perceptual shifts through a bright, mostly open space, marked with minimally rendered buildings that cast no shadows. Throughout the arc of Serious Games, Farocki dwells on this fact: the software used in therapy is cheaper than the software used in deployment training. One consequence is that the former does not depict shadows; the lack of shadows gives these scenes weightlessness. Economic reality is not distinct from feeling. One determines the other, and neither has a weight that is as absolute or as serious as the absolute seriousness of being. Both. Driving along a desert road, the feeling that you could keep driving forever. Immersion puts the viewer in a vehicle. It’s overcast and there are periodic clouds of smoke, explosions. In Serious Games I: Watson is Down (2010), the vehicle moves off-road, over rocky, uneven terrain. The viewer looks for someone or something. At some point, someone dies.

In Serious Games III: Immersion (2009), and in Serious Games IV: A Sun with No Shadow (2010), the two channels dichotomize internal and external experience, while also questioning the relationship between what is essentially private and what can be shared. The right screen shows a person in goggles; the left screen shows the animated images visible within the goggles. (In my own memory of watching the videos, the two channels of the installation overlap. I mentally splice them into each other and then have to work to mentally separate them out again.)

Towards the end of Immersion, after the veteran has removed his headset, he smiles. An off-camera audience applauds. Farocki’s viewers have been misled—this isn’t an authentic therapy session, but one staged for a group of professionals, a model session demonstrating how therapists can use simulation software with veterans experiencing Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. Since the audience does not appear on camera, they remain a fact rather than a presence, and a perverse one: in a way undermining the potential intensity of the veteran’s narration. Once the audience is established as a fact, it becomes harder to imagine conditions of actual sharing, or that such treatment could be effective against the reality of trauma. The staging of therapy reinforces Farocki’s and Farocki’s viewers’ distance from the veteran’s real interior experience. Once the fiction of the therapy’s session is established, the veteran loses his specificity, becoming a stand-in for all veterans. As viewers we are distant not only from this veteran’s real interior experience, but from any veteran’s or all veterans’ interior experiences. Another divide: between realities, which are nowhere and multiple, fictions-based-on-facts, the desert, recollections of memories that may or may not be real. But all experience is real, right?

Though the fact of the audience is revealed at the end of Immersion, and it becomes clear that both therapist and veteran are performing—in fact employed by the game company—the viewer does not learn whether the veteran is or is not actually a veteran, and the therapist a therapist. Does it make a difference, since in either case they are performing, whether the veteran has really served?

In the exhibition at Hamburger Bahnhof, the Serious Games videos were prefaced by two older works. Nicht löschbares Feuer (Inextinguishable Fire, 1969) addresses the portrayal of violence in Vietnam in American media; Schnittstelle (Interface, 1995) reflects more broadly on the history of the moving image as a political technology. Within these two works are many of Farocki’s more iconic moments—seated at a desk in front of the camera as a young man in 1969, he puts out a cigarette on his exposed forearm: with this self-inflicted violence gesturing towards the violent effects of media-visualizations of war. Both older works refer directly to the space of Farocki’s editing studio, his commentary and thinking, sometimes one or two steps removed. One shot in Interface shows Farocki’s hands hovering steadily over a control panel in an editing suite, waiting for the moment to make a cut. Images appear as frames within other images. The workers leave the factory over and over again. These two works function in several ways as a frame for Serious Games: they ground the more recent videos’ investigation of the relation between images and the technologies of war, images and the languages of war, images and the ways people live with war, external or inner. They also bring the artist into the room more visibly, as editor, commentator, and actor.

Farocki himself does not appear in the more recent works. Now, remembering watching them, I am overwhelmed by the absence of leadership they imply: in this training session the computer takes the place of teacher, and in this therapy session the computer takes the place of therapist. Instead of being a tool for the teacher’s or therapist’s instructions, the teacher and therapist seem to implement the language and guidance supplied by the computer. Where does Farocki’s own absence in the more recent works fit into this picture?

As I grow to trust images less and less, I feel emboldened and challenged by Farocki’s work. In what ways can looking at something (experience?) and really seeing it provide forms of political resistance?

In October I took an overnight train from Vienna to Berlin alone. I spent most of the eleven hours reading the same five pages of a book, nodding off in a dark Sitzplatz until the sun came up in Dresden. I was one of the first visitors to the Hamburger Bahnhof that morning, and for most of my visit, the only one in the Harun Farocki exhibition. Alone in the gallery with Farocki’s soldiers and veterans, I developed a fantasy of the reportedly charismatic German artist talking with these young soldiers and instructors in Twentynine Palms off-camera, asking them about the visual simulation technologies in their lives. What kind of gap marks the possibility for understanding between a soldier and a civilian? Or between any one suffering from their own trauma, and any other person?

As I try to understand the impressions this exhibition has made on me over the past months, I filter my remembered experience through things I’ve read, seen, and heard. About Farocki’s personality as a teacher and artist: in the months since his death and since my trip to Berlin I’ve read several very affectionate elegies and remembrances full of admiration, longing, and inside jokes, which I am outside of (like, the November issue of e-flux Journal). He used to teach in Vienna, the city where I currently live and in which I remain new. Friends tell me about emails he once sent, and about his openness, his love of driving, his cool t-shirts—one printed with something like “I do something with media.”

I read a few things he wrote about making Serious Games, and about the broader shift in his attention towards animated images and virtual realities. In one statement in 2008, written before the production of Serious Games, Farocki outlined his intentions to shoot actual therapy sessions between military therapists and veterans from Iraq. This was before he was denied access by the United States military to actual therapy sessions, “—for ethical reasons,” Farocki adds wistfully in a recorded presentation given together with his collaborator and partner Antje Ehmann at the Slought Foundation in 2010. As if the United States military upheld higher ethical standards than a couple politically critical artists. In his 2008 statement he explains that their “approach to documentary filmmaking means we never intervene in the situation, we simply allow it to unfold as (it would) if we were not there.” (Farocki, in an exposé written in advance of the production of Immersion, published in 2013). It is a fundamental but still impossible metric in documentary ethics, to simply allow something to happen, “as if we were not there—” and another way to think about Farocki’s absence. Could any patient working through a trauma possibly enter into the world of their trauma in the presence of a documentary crew? Of course, in some ways, people do this all the time, act under surveillance, spill their guts. The furtive presence of the audience in the edit of Immersion included in the Serious Games exhibition, and the ambiguity of whether the person performing as patient in this video is also actually a veteran or just an actor—a result of the US military’s executive decision to forbid Farocki’s presence in an actual therapy session—makes this tension between therapeutic intimacy and surveillance even more felt. Farocki, his collaborators, and many of his viewers, including myself, have never been in the room of an actual therapy session with a veteran. We fall on the outside of this experience of war.

In exposure therapy, a patient is made to confront the narrative and details of a traumatic event: by repeatedly re-remembering it, by verbally telling the story of their trauma to a therapist, and by revisiting actual places or objects, or virtual simulations—as performed in the Immersion session. Having reportedly learned from the post-war torment of many American Vietnam vets after they returned home, the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs advocates exposure therapy to “help correct faulty perceptions of danger, improve perceived self-control of memories and accompanying negative emotions, and strengthen adaptive coping responses under conditions of distress” (United States Department of Veterans Affairs). The first version of the “Virtual Vietnam VR scenario” was used in exposure therapy treatment for Vietnam veterans experiencing Post Traumatic Stress Disorder in 1997, after many vets had been living with the effects of PTSD for more than twenty-five years; earlier versions of the software were modeled for therapeutic use among Vietnam vets in the early nineties. The USVA distinguishes exposure therapy from similar therapeutic models in which patients are simply asked to verbally recount a traumatic episode repeatedly. Similar models have been used among people experiencing trauma from physical or sexual abuse. Significant to the exposure therapy model is that it involves external stimuli.

What is this actually like for people? One study reports a higher number of vets meeting the criteria for “major depression, generalized anxiety, or PTSD was significantly higher after duty in Iraq (15.6 to 17.1 percent) than after duty in Afghanistan (11.2 percent) or before deployment to Iraq (9.3 percent) (from a study by Hoge et al., 2004, published in a 2006 report by Rizzo et al.) A more recent study reports that “the particular challenges characterizing the ground wars in Iraq and Afghanistan have produced significant numbers of active service members and veterans at risk for developing PTSD and other psychological and behavioral health conditions (also by Rizzo et al., 2014, at the USC Institute for Creative Technologies). But, the abstract of another recent report begins: “Despite efforts to increase the availability of prolonged exposure therapy (PE) within the Department of Veterans Affairs, little is known about the acceptability of PE among veteran populations” (Kehle-Forbes, et al., 2014). A statistic reported on a special CBS 60 Minutes “The War Within: Treating PTSD” in 2013: “Two million Americans have served in Afghanistan and Iraq. The Veterans Administration tells us that one out of five suffers from PTSD” (CBS).

What are the gaps between the USVA’s reports, or reports compiled by academic and medical researchers, researchers representing the virtual reality software producers, and veterans’ actual experiences?

I start to read about experiences of veterans returning to the states from the recent and ongoing wars the United States fights in the Middle East. Concerning Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder among vets returning from Iraq and Afghanistan in the U.S., the misunderstandings among vets and civilians may be foundational, actually defining the trauma many soldiers experience after returning home. David J. Morris writes about his own experiences, that

“Going in for therapy at a Veterans Affairs hospital is a lot like arriving at a large airport in a foreign country. You pass through a maze of confusing signage. Your documents are scrutinized. There are long lines you must stand in and a series of bureaucratic rituals that must be endured before anything resembling a human encounter occurs” (Morris, 2015).

Even the experiences surrounding therapy contribute to an ongoing experience of trauma. Many say they feel the civilian population cannot possibly understand what they’ve been through; those whose lives remain outside of this experience don’t know what it’s like. “How can you live a life when everyone is afraid of you? You go to town and people say ‘that’s the crazy vet, don’t mess with him’” (Gene Dowdy, 2013). Whether or not experience can ever be understood as common between people—whether trauma can ever really be collective—there is one pervasive, stark attitude that says: either you’ve served or you haven’t. One symptom of the misunderstandings among soldiers, civilians, therapists, and veterans is detachment: seeing one world around you while feeling that you inhabit another. An existential distance, like the impossibility of seeing what someone else sees. Farocki’s Serious Games videos do not quite provide access into the traumatic experiences of soldiers or veterans; they help describe the difficult expectation of access. Discussions about virtual realities tend to focus on the visual world, but central to real healing therapies is the act of listening.

It may go without saying that having access to statistics about how many veterans experience PTSD does not provide insight into their experiences, or into the therapeutic process. It does not clarify what, in these sessions, is really being exposed. Unlike Farocki, CBS’ 60 Minutes team was permitted to attend therapy sessions with veterans—or, at least, within the framework of their 2013 program it is not questioned whether there’s any possibility that the conversation they record might be staged. Are the veterans recorded on camera for the American public also, in some ways at least, performing as themselves? Is it that the USVA trusts a major United States media network to portray the torment of the nation’s veterans without questioning or deriding the mechanisms and ethics of the nation’s wars—while Farocki remains a clear outsider, not only a foreigner, but an artist, a critic? Relying on second-hand experiences in place of a more personal experience of war-related trauma, I am relying on understanding by watching something, learning to respond to cues—rather than really looking or really listening, the way a real therapist should, not the way a computer does, or even a documentarian. There is a big difference between approaching the Serious Games videos as art—at best advocating for really looking or really listening—and as records of other people’s experiences.

Can the computer visualizations used in training or in therapy help define a kind of realism? Can Serious Games? Realism or reality: the order of things, the edge between the word and the thing it names, its images—these that are everywhere, that are manipulated, that manipulate. Over the last years Farocki turned his attention increasingly towards animated images, simulated realities: away from documentary images, which are too much everywhere. In animated images such as those featured in Serious Games, life is manipulated and manipulates in an open, direct way, taking both image and life as potential propaganda, weapons, “operational tools” (Farocki, with Antje Ehmann, 2010).

The exhibition in Berlin opened in February 2014 and was originally scheduled to end in July; following Farocki’s sudden death at the end of that month, it was extended until January 18, 2015. I would not have seen the exhibition if it had not been extended, if he had not died last summer. But somehow, when I visited the exhibition in October, I didn’t yet know that Farocki had died. In July I’d been hiking, I moved a couple times: there was a gap in my paying attention. I hadn’t seen the news. After seeing the exhibition I catch up on the stories I had missed before, about Farcoki’s death, and wonder again about Farocki’s absence.

In February 2015 I return to the animated desert, to my train ride, my Dresden sunrise last October, through the same five pages of meditative and distracted reading, months of myself. Unlike the veteran or the actor telling his story in Immersion, I don’t have a mission, only the impressions of images. I arrive in order to be transported and it works. Reconnaissance: I’ve never been there. The veteran, or actor, removing his virtual-reality goggles, smiles. His trauma is his reality, our shared virtual reality—and also something else, equally unexposed.

Dowdy, Gene, in “The War Within: Treating PTSD,” produced by Ashley Velie with correspondent Scott Pelley for CBS 60 Minutes, November 24, 2013. Accessed online May 9, 2015.

e-flux journal Issue 59: Harun Farocki, ed. Antje Ehmann, Doreen Mende, et al., November 2014. Accessed online April 30, 2015.

Farocki, Harun. “Immersion (2009),” Killer Images: Documentary Film, Memory, and the Performance of Violence, ed. Joran Ten Brink and Joshua Oppenheimer, New York: Columbia University Press, 2013.

Farocki, Harun with Antje Ehmann. “War – Media – Art: The Image in Question,” conversation at the Slought Foundation, Philadelphia, September 16, 2010. Online resource accessed May 9, 2015.

Huldisch, Henriette. “Some Games Are More Serious Than Others,” exhibition guide and text printed for “Ernste Spiele,” Hamburger Bahnhof – Museum für Gegenwart, Berlin, February 6–July 13, 2014 [extended to January 18, 2015]. Received October 24, 2014.

Moris, David J. “After PTSD, More Trauma,” The New York Times, January 17, 2015. Accessed online May 9, 2015.

Rizzo, Albert, et al. “A Virtual Reality Exposure Therapy Application for Iraq War Military Personnel with Post Traumatic Stress Disorder: From Training to Toy to Treatment,” in NATO Advanced Research Workshop on Novel Approaches to the Diagnosis and Treatment of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder, ed. Michael J. Roy, Washington D.C.: IOS Press, 2006. Accessed online May 9, 2015.

Rizzo, Albert, et al., USC Institute for Creative Technologies. “Virtual Reality Exposure Therapy for Combat-Related Posttraumatic Stress Disorder,” Angeles: IEEE Computer Society, 2014, pages 31–37. Accessed online May 9, 2015.

Ruzek, Joself I., et al. “Treatment of the Returning Iraq War Veteran,” from Iraq War Clinician Guide, United States Department of Veteran Affairs website. Accessed May 9, 2015.