Hannah Clark

Parasomnia

ISSUE 47 | NOCTURNE | DEC 2014

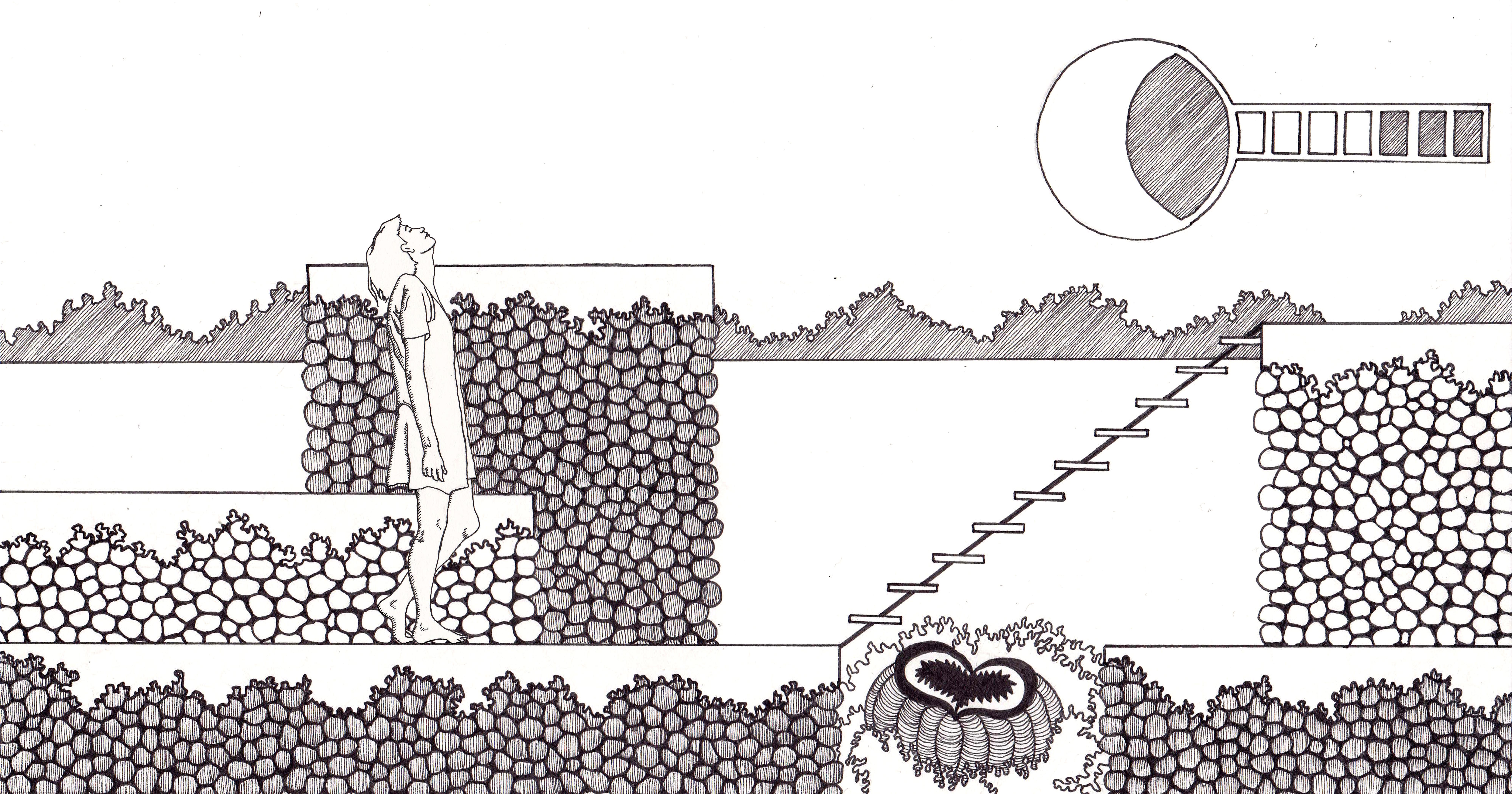

Illustration by Antonia Stringer

“The sleeper is the proprietor of an unknown land”

I once woke up sitting on the toilet, my somnambulant journey paused tenuously over the porcelain seat. I would often wake in the middle of the night to find myself in the basement, in the kitchen, on the living room couch. I shared a bedroom with two sisters and at night it became a hive of snorting, mumbling and locomotive bodies. Tessa had an oppressive high-pitched snore that would occasionally break into worrying nasal coughs. I mumbled incessantly, never constructing words but intonating dramatically into my pillow. Kelsey sat up in bed and stayed there, eyes shut, as naturally as one might roll over without waking.

The human brain cycles through five distinct stages of sleep, defined by the rhythm of brainwaves as they appear on an EEG scan. Wave frequencies decrease from stage I to stage IV or “slow wave” sleep, considered the deepest and most restorative phase in the cycle. Following a period of slow wave sleep the brain enters the Rapid Eye Movement phase, where the paralysis of major muscle groups occurs and EEG recordings show brain activity that is remarkably similar to that of a waking brain. After about 10 minutes of REM the cycle begins again. Subjects woken from REM sleep usually report elaborate, vivid, and emotional dreams; subjects woken from non-REM phases report fewer dreams, and when dreams are remembered they are more conceptual, less vivid and less emotion-laden.

We dealt with one another aggressively, driven by irritability and fear. The reaction to being woken by a possessed sister was to exorcise her as quickly as possible without getting too close, usually by shouting her name or bombarding her with stuffed animals. If Tessa fell asleep first one of us would get up and heave her limp body over in an attempt to shift her mucosal reeds out of their whistling orientation. One night I woke up to find her on her hands and knees near the door, clumsily running her hands across the wall and along the baseboard. When I got her attention she said that she had to go to the bathroom but couldn’t find the doorknob. Propped up on my elbow I tried to walk her through the situation, told her to stand up, told her to reach her hand out toward where the knob NORMALLY IS. She stood confounded. I threw my pillow to effect her return to the room and when her eyes met mine with a renewed attention, began my directions again.

* * *

“Let a man lay himself down in the Great Bed and his ‘identity’ is no longer his own, his ‘trust’ is not with him, and his ‘willingness’ is turned over and is of another permission”

A genetic disorder called Fatal Familial Insomnia involves miss-folded proteins called prions that change the structure of brain’s thalamus, which is the area responsible for regulating the sleep cycle. Sleep EEGs of FFI patients show a mixture of rhythms that are not typical to wakefulness or to any of the sleep phases and indicate a state of “subwakefulness.” As the disease progresses victims first lose slow wave sleep, then eventually their REM stage disengages from its circadian cycle and intrudes into the waking state. This state of “parasomnia” resembles REM but is not accompanied by muscle paralysis, meaning external behaviors are consistent to a waking state while brain waves indicate a dream state. Sufferers of FFI remain in this liminal mode almost constantly.

* * *

Once I woke to the slam of a door. Kelsey was standing in the middle of the room, wrapped in her comforter, the bottom end trailing behind her and into the doorjamb. She leaned forward, tethered by the blanket. Tessa and I watched her walk lazily in place for a moment as we assessed her level of consciousness. We whispered her name and her unfamiliar body didn’t respond. Our whispers became sharp, we shouted desperately until she finally looked up and after a pause, burst into tears.

* * *

FFI progresses in four distinct phases. The first is characterized by sporadic insomnia, panic attacks and general paranoia; the second by the onset of hallucinations; the third by the total inability to sleep and rapid loss of weight; the fourth by dementia, muteness and eventually death.

In 2006 psychologist Joyce Shenkein and neurologist Pasquale Montagna published a case report on a man referred to as DF who exceeded the average survival time of FFI by almost a year through self–directed treatment. When DF was diagnosed in 2001, he was 10 months into phase I of the disease. He bought a motor home and was determined to travel the United States and complete a novel before phase IV set in. Whenever he experienced a bout of insomnia, he would stay at a rest stop until he’d achieved sleep. He memorized strings of numbers and would recite them before allowing himself to get back on the road. He reported being stranded at times with prolonged insomnia, only realizing that days had passed when he looked at the date on a newspaper.

* * *

One night a police officer came to our door with my brother at his side. He was red-eyed and barefoot wearing only pajamas. He had sleepwalked right out of the house and down the street. The cop responded to a call and found him standing in the middle of the cul-de-sac, asleep, yelling. My brother had roused an attentive but cowardly neighbor who, not knowing what name to shout from the safety of his living room window, had called 911.

* * *

“She who stands looking down upon her who lies sleeping knows the horizontal fear, the fear unbearable”

DF began a rigorous vitamin treatment, taken every night at 9 PM which consisted of niacin, Vitamins A, C, E and D, blue-green algae, brewer’s yeast, b-complex, zinc, magnesium, choline, inositol, PABA, grape seed extract, CoQ-10, a Tiger’s Milk bar, tryptophan, 2g of Melatonin, and finally a nasal injection of gelatinous B-12. After each treatment DF could sleep for up to 5 hours.

Around month 15 of his illness, DF’s vitamin regimen lost its effectiveness. He moved on to experimenting with a combination of ketamine and nitrous oxide, which provided 15-minute-long bouts of sleep.

By month 16 DF rarely slept. He said his insomnia was like “repeatedly approaching an open doorway, only to have it suddenly become inaccessible.” He had a constant fever and short-term memory loss, which he combated by keeping detailed notes and to-do lists. Periods of muteness and signs of dementia set in. DF described sitting entranced for hours, getting up for water and then forgetting why he went into the kitchen and returning to the couch without it. He would repeat this cycle for hours, without ever obtaining water. He would have difficulty understanding the notes he had written himself. During these stupors he would be unable to speak, then would suddenly come forward and request a new gamut of drugs, reporting that throughout his muteness he had been contemplating his treatment.

* * *

On Christmas Eve when I was 14 I stood watching my grandmother fumble to put on her coat. In her right hand was the tab to her zipper, in her left she held a house key that hung from a lanyard around her neck. With gentle persistence she tried to force the key into the zipper, stopping and starting again, searching for the configuration that allowed the two parts to function together. She finally asked me for help and I was too ashamed to look at her as I swiftly closed her jacket.

* * *

“We look to the sleeper for the secret that we shall not find”

In the 19th month of his illness DF began electroconvulsive therapy to induce seizures, which would be followed by long periods of restful sleep. The consequences of this treatment proved too severe; he reported experiencing anomia and retrograde amnesia that wiped a few years from his memory.

In month 22 DF purchased a sensory deprivation tank and would successfully obtain sleep by combining immersion with the use of nitrous oxide. He described waking up in the tank to a roar of hallucinations, uncertain whether he had passed into a waking state or simply died.

* * *

Some time later we began visiting her in a nursing home every weekend. I learned that she was notorious among the staff members for wandering the building in the middle of the night. During a trip from her bed to her toilet she often found herself in one of the sterile hallways that unfolded in endless identical turns. A beeper-clad caretaker would find her in the lobby, near the cafeteria, or across the hall from her room, pristinely disoriented. I was told that she had “a bit of Sundowners.” Her dementia amplified as night approached due to a combination of exhaustion and the chaotic spread of shadows cast in low lighting.

* * *

“Ah, to be an animal, born at the opening of the eye, going only forward, and, at the end of the day, shutting out memory with the dropping of the lid.”

In general, DF reported that his oneiric states were serene, a multisensory experience involving images, voices and smells. He described entering a room filled with everyone he would want to be with, including deceased friends and relatives, who would say comforting words. He experienced his waking-REM state as a sort of radical self-awareness. He said his mind was full of “wounded children” who were unaware of the events that had injured them, and were thus unable to rise above their experiences. He said his FFI allowed him to soothe these children with “adult insight.”

He wrote, “To the outside world I am dead and gone, but to myself, I am still here, in this wonderful place, and it is they who have disappeared.”