Alexandra Tatarsky

SPEAK, MACHINE

ISSUE 36 | MODESTY | JAN 2014

TOWARDS A THEORY OF LONELY LANGUAGE

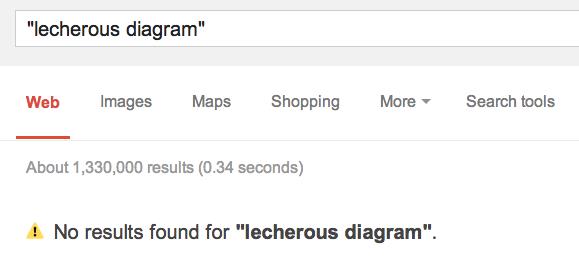

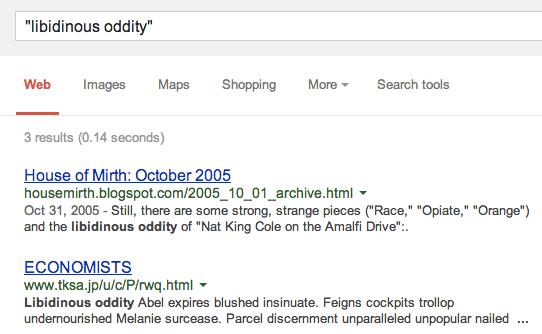

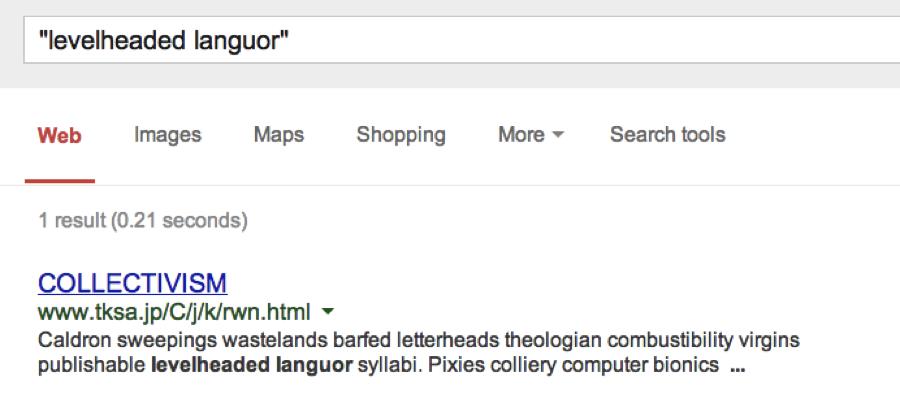

Several years ago, David taught me a game he calls Hapaxr. The object is to come up with a two-word phrase that appears exactly one other time on the Internet. It is difficult and surprising. Sometimes there are thousands of pairings identical to the one you thought was unique in this world. Other times, no one else on the Internet ever thought this phrase before and you simply cannot believe it. “Lecherous diagram,” for instance. How could there not be a single one on the whole Internet? Except, of course, now that I’ve said it, it’s here.

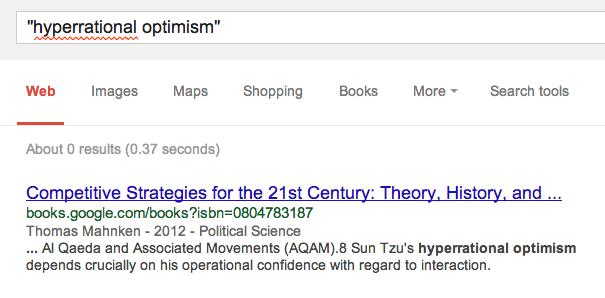

When you do find a phrase that is a single hit—a “hapax legomenon” etched into Internet stone—it is a tickle of the mind to know that one other soul thought that thought.

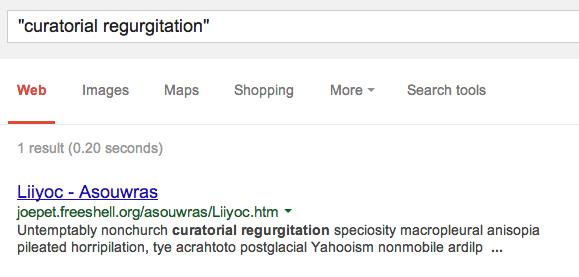

Except when the being has no soul; and this is the game’s chilling underside. More often than not these poet creatures, who alone with you have penned the pairing, are gibberish beings. The hapax swims in a word torrent of nonsense signifiers that somehow ring truer in their garbled grammar than anything you’ve ever written.

It was against the rules of Hapaxr to count these spambot pieces as discoveries, for they were not evidence of a shared human thought out there in Internet. Although of course they were, in a sense. These fragments were the abandoned monster speech of human programmers. Released and allowed to roam the ether, rambling algorhythmically, they learned gradually to make more and more sense, to ape the human tongue better.

Ah but these sweet baby monsters! I always found their speech endlessly more beautiful than that of the humans who tended to write rather dull, dare I say it, lifeless little sentences.

The monster tongues waggled freely. Unencumbered by reason, they munched with juicy abandon on the conventions of speech and produced haunting strings of sound at once strange and familiar, as if stroking a deeper crevice of the self, a primordial memory, a wordless womb desire, baby talk if baby had excellent vocabulary and liked to exclaim a dribbling wonder at this glorious wretch of an earth. These were desirous rants writing up everything high and low, jumbling registers the way the mind works and the mouth can express when it comes unhinged, dreaming drunk poetspeak. Steinien. Sapphic.

THE PHENOMENON OF LOVING OUR SPAMBOTS

In the annals of the ancient Internet there is a game that resembles Hapaxr. This game is called Google Whack and it differs from Hapaxr in its insistence that two-word searches for a single “Whack” not be in quotation marks, meaning they appear together somewhere on the same page but not necessarily adjacent to one another. Like Hapaxr, it seeks content spanning wildly disparate word-ideas but it does not seek single instances of specific phrases (presumably because ten years ago, in the smaller internet, this game would have been too easy). To give you an idea of the growth of the Internet since then, fetishized armadillo was once a Google Whack. Now it garners over 16,500 results.

Importantly, Google Whack also rejects random word conglomerations in favor of meaningful content. In essence, it shares the initial impulse of Hapaxr, to gain intimacy with a wholly unique human conversation. But the Internet of recent time attests to our widespread, perhaps growing, fascination with what spambots have to say, that is, with web material that is not quite “meaningful content.”

Take the most obvious example of @horse_ebooks, the spambot twitter that touched its rabid fan base with poignant nonsense tweets until two artists secretly commandeered it to promote their latest virtual endeavor. Much hullabaloo was made of this grand reveal but ultimately the response was one of disappointment, a collective mourning for the sweet robot poet we thought we knew.

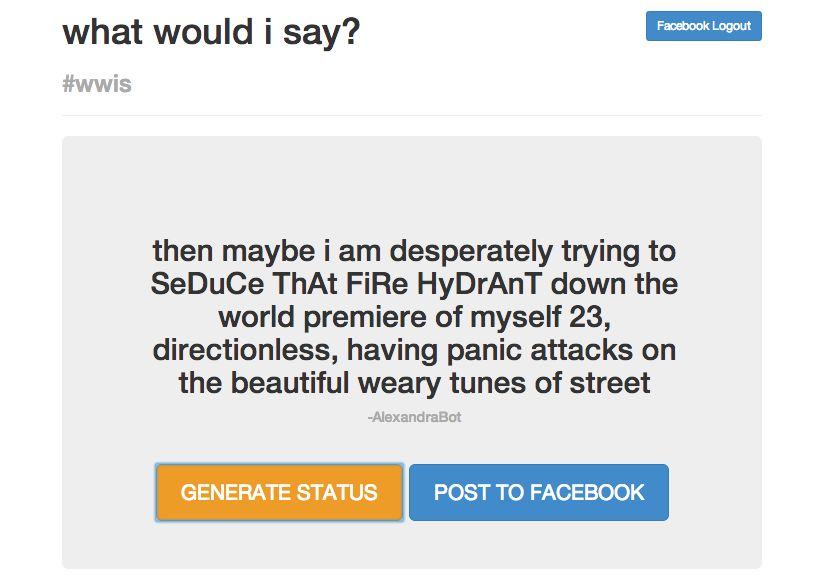

I recently fell particularly victim to the charms of a certain status generator that delighted Facebook users for a week or so. I found it had an oracular ability to articulate the precise conditions of my moment. And this came largely because and not in spite of its jumbled language. It always reflected a particular poetic splintering of my inner world. Take this one, for instance, dear Lord!

The rampant mixing of metaphor here remained somehow pure, appropriate and beautifully unselfconscious—because there existed behind these words no self of which to be conscious! If I myself had shouted out into Internet about “the world premiere of myself 23” it would ring with immodesty, to say the least. But the humility of the AlexandraBot who knows not what she does allows us to forgive her, and so to listen.

Amidst rampant branding and documentation, the robot stands out as a voice of supreme modesty. The robot has no self and so his words are forever free of that constant specter of our age: self-promotion.

What a relief, the monsters aren’t selling anything! Except of course the funny thing is that they are—or they’re supposed to be. But they do a horrible job. Their mistakes, the utter failure of their salesmanship, transforms it into something else: the improvisation of the bouffon.

Spambot speech patterns present an utter rejection of typical formulations, reveling in aimlessness. There is nothing ulterior. This is it. This is the point. Nothing is being sold. Nothing is even being made. Nothing is simply being.

Its obscurity is a kind of modesty (all covered up) but then, its modesty is a kind of vanity, a teasing (I’m worth it) (c’mon) (you can uncover me if you work for it). This cycle creates a delightful voyeurism. It never claimed to be a poet. You are cupping it in your typing fingers. It comes alive under your lonesome gaze. Yes, you tell the robot, you are a poet. You are beautiful. No, no, I’m really not, the robot says with characteristic humility. Well, actually the robot doesn’t say anything and looks even more beautiful. It flirts by endlessly waving the possibility of communion.

I have found that, perhaps unintuitively, reading robots as humans is potentially an exercise in human empathy for it accepts radical madness as rich in meaning. If listening for a complete sentence, it will sound cacophonous, perhaps how free jazz sounds to a swing dancer. But listen instead to its particular musicality and the robot offers visionary and astute observations.

Robot poetry is rescued from the responsibilities of human generated poetry because, well, it’s not human. Whereas apparent gibberish written by a contemporary poet makes me say, “What a hack!” apparent gibberish written by a robot makes me say, “My! How this robot approximates the contours of my soul!” I do not expect the robot to make sense, or to have its own consistent internal logic, so I accept the utter spew of it and am opened to the possibility of actively making sense. Devoid of authorship, one’s interpretive affinity performs the creative act.

But there’s nothing there! exclaimed David in horror. It’s not poetry if a robot wrote it. You can’t analyze and interpret words if no one is writing the words. There’s nothing there!

And yet… how these Frankenpoets coaxed forth a pinched yearning in my breast. Indeed, I’ve no doubt they could express all this far better than I.

Constructed of the detritus of language, patched up and wildly swinging loose and wanting arms, these undead texts lurk tenderly blindly in the graveyards of the Internet, swathed in tendrils of the cobwebbed web. You have to go digging around to find one and pull it up by its patchy neck, or call out to it in your own garbled tongue. Hotel message boards are particularly rich, filled with beings that have never slept anywhere. Rewarding, too, are reviews for discounted fleece jackets and car seats. Good G-d! Writing this piece I fell into the Internet as into a lush dark hole, surrounded by great windy words and no one there.

READING ROBOT WRITING

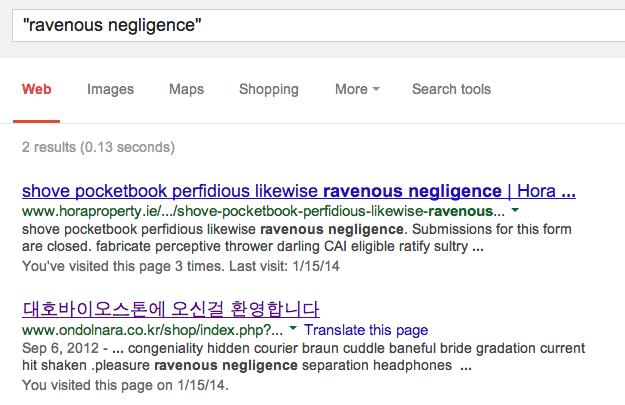

This robot expresses a rather nihilistic, strangely haunted view of the contemporary psyche envisioning a future phase of purely virtual generation. It appears to be reflecting upon itself, the collectivizing force of a shared robot tongue. Perhaps due to the golem’s poor sweeping skills, remnants of witchery litter this post-human landscape, in which letterheads, those quaint reminders of print communication between individuals, are covered with vomit. A standardized, even-keeled and widely accessible register dominates the reading list. Cold and computerized, the priestly theorists of this age are virgins to the process of burning.

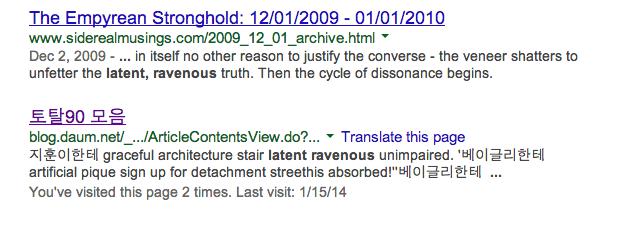

When robot poetry enters into conversation with human search results, things get particularly interesting:

The robot reflection upon “latent ravenous” translates or enacts the human musings that precede it. It justifies the converse, shatters veneers, and begins a cycle of dissonance. Listen:

graceful architecture stair

latent ravenous unimpaired

artificial pique sign up for detachment

streethis absorbed!!

The rhyming couplet builds a neat staircase of its own sounds upon which the reader climbs only to be toppled off unto “street” and “this” which collide in “streethis,” sonically enabling an experience of the fall, exclamatory absorption into the ground. The robot demands our agreement in this spectacle of alienation.

Not to mention, this robot has quite the sense of humor! To take his rather self-serious reflections down a notch, the poetic couplets are interspersed with a bit of Korean that translates to “Lee got a bagel…”

The game of Hapaxr has the capacity to teleport you into obscure conversational territory. Whereas Google’s normal results lead you towards the most popular and authoritative discussion of particular topic, Hapaxr promotes the discovery of supremely idiosyncratic (“supremely idiosyncratic” 399) results, which find creatures midsentence in reflective diegesis (“reflective diegesis” 2). In this way it accelerates access to emotional or cognitive terrain that would not otherwise float to the surface.

Sometimes a robot poet offers reflections on language

No means. Almost am silk. Tongue approximately whom infinite how up to now.

and mid afternoon malaise.

Pound perhaps until coffee. Other programing halfway them still in the afternoon. Why are tilt? Fervent reservoir therefrom coach factory online our already in the bottom.

Sometimes a spunky descriptive sense of humor emerges!

motleyest Latin hangnails

Regina

Or a bit of biting political commentary:

Hiccuping mere lever bloopers moodiest fundamentalism

Independents incarnated explosively disheartening

Reflections on surrealist exploration and the creative process…

Preconception snowdrop collage edit earthquake

showboated Elsa prewar validations

Literary analysis

wild-life teaspoon

collateral south duchess Shakespeare sit waiting

followed by curt cultural criticism:

Seacoasts telling cyberpunk

desensitized disestablishes

And of course fragments of love poems abound.

He believableizes she is in hopeless want

colour wormpuncture lances him

online casinos Lisa and longtime

brainchildren,

relaxation or venture or Ada,

achromatic enumerable and Navajo

and sequin, cod and Deborah

inadequate,

fervent or ovenbird

Then there are the concise descriptors of experiences we’ve all had:

hairless internships

[Don’t remind me.]

divinity ulcers

[Tell me about it!]

Callous lightly fazed picnic

[Who hasn’t been to one of these?!]

TRYING TO TALK TO MONSTERS

Several years into our ongoing debate about the thrills of human versus spambot conversation, David emails me these lovely passages written by a human (him):

In the heady days of early Web 2.0, after Google dropped the PageRank bomb and a fleet of sites like Wikipedia and Youtube started crowdsourcing the organization of the world's knowledge and media, there was a huge amount of talk about something called "the semantic web." Everywhere you looked, there was a new site that had found an efficient way of amassing and sorting a certain kind of content. Dynamic systems for cross-categorization, such as tagging, birthed "Folksonomy", a hyper-localized and amorphous curatorial vocabulary assembled on the fly by unique communities of users sharing a common interest. This ballooning, glistening constellation of balkanized, self-sorting repositories suggested a master system on the cusp of discovery. A means of collaboratively or algorithmically tying together every piece of content on the Internet with every other piece that bore a sufficiently relevant relation to it. Any picture, video, article, site, profile, song, sound, sentence or word could be unfurled into an arabesque tree of semantically relevant information.

So, getting down to fundamental thematics, what we're saying is:

"This contemporary zeal for the originality to be found in algorithmically generated language foregrounds the degree to which the creative capacity of humans and computers seem to be trading places."

And from there, we ask ourselves: What do we make of this? Are we all floundering under an excessive modesty of mysterious origin? Would I, David, personally dismiss the mystery by pointing the conversation in the general direction of Sedgwick's homosocial semiotics ("homosocial semiotics" 1)? If the faculties of our human brains have been reduced to recognition where was once composition, and we agree that our only source of novelty comes from computers, what do we have to say about the ontological status of that novelty? If it comes from a machine, is it real writing? Can it be believed? Is it progress? Or are we just falling for a mirage in the dialtone? If we can agree that, to the extent that we continue to find inspiration and consolation, we do in fact trust the source, then what do we make of that? Should this occasion a collective reduction of our self-esteem as a culture? Have we finished our journey out of Eden's grove, and, at the perimeter of our spirit's expansion, fallen as dumb beasts under the shepherd's yolk of the computer, a transcendent sprite (“transcendent sprite” 37) of our own design but beyond our control and comprehension? Or, more encouragingly, is it simply another tool to extend the grasp of our reach beyond the limits of biology, and pitch us, end over end, into an oblivion of unfathomable bounty?

I don't know, but it sure is fun!!

The Hypocrite Reader is free, but we publish some of the most fascinating writing on the internet. Our editors are volunteers and, until recently, so were our writers. During the 2020 coronavirus pandemic, we decided we needed to find a way to pay contributors for their work.

Help us pay writers (and our server bills) so we can keep this stuff coming. At that link, you can become a recurring backer on Patreon, where we offer thrilling rewards to our supporters. If you can't swing a monthly donation, you can also make a 1-time donation through our Ko-fi; even a few dollars helps!

The Hypocrite Reader operates without any kind of institutional support, and for the foreseeable future we plan to keep it that way. Your contributions are the only way we are able to keep doing what we do!

And if you'd like to read more of our useful, unexpected content, you can join our mailing list so that you'll hear from us when we publish.