Michelle Bentsman

The Last Look

ISSUE 36 | MODESTY | JAN 2014

I. SKIN

“Peel off the napkin

O my enemy.

Do I terrify?-------

The nose, the eye pits, the full set of teeth?

The sour breath

Will vanish in a day.

Soon, soon the flesh

The grave cave ate will be

At home on me

And I a smiling woman.

[... ]

The Peanut-crunching crowd

Shoves in to see

Them unwrap me hand and foot ------

The big strip tease.”

The reader finds himself alone in the room with the Lady, and she commands: “peel.” Here we are, reader, doctor-enemy, in the doctor's chambers, apparently peeling a napkin. But a napkin is so rarely peeled. To peel is to separate a part from the whole, to remove an outer layer by careful unrelenting force. When we peel, we tend to peel skin away, to reveal what's beneath.

Lady Lazarus is eager to reveal what's beneath. She names her parts, the nose, the eye-pits, the teeth, augmenting our sense of her body. We even learn the smell in her mouth; she is sour, but not for long. Indeed, she is ready for tomorrow, when her flesh will decay, when she will be entirely a corpse, and a smiling woman, too.

Between this world and the next, she exposes herself by our hands. We are implicated in delaying her death and in violating her body. Of the latter, she demands that we do, and that we look. There is something titillating, perhaps even pornographic about this. We have delayed her gratification, in death, and now we look upon the corpse-woman-object that we have exposed, by way of her defiant demand to peel. She will get her final release. Soon, she will be a smiling woman, in feminine afterglow, la petite mort now grand.

Geoffrey Gorer makes a number of compelling distinctions between pornography and obscenity in his essay, “The Pornography of Death.” Pornography, “the description of tabooed activities to produce hallucination or delusion,” is far rarer than obscenity, and its enjoyment is private. Meanwhile, obscenity is a universal aspect of society, and its enjoyment is a social, situational phenomenon.

Thus, the enemy-doctor, alone with Lady Lazarus, the soon-to-be-corpse, Herr Doktor, enemy-reader, alone with the text, is capable of enjoying a pornographic moment, one sprung from terror. As soon as the brutish, boorish crowd, with peanuts spilling from their mouths, come in to see the Lady, she becomes an obscene spectacle. No longer is the reader-enemy-doctor peeling Lady Lazarus. Now, the enemy becomes “them,” and they “unwrap” her. Lady Lazarus doesn't hesitate to classify this spectacle for us: we are watching “the big strip tease”. This unwrapping also titillates and violates. It is an inverted mummification, an exposure of the corpse. She is undressed, unwrapped and made unready for society, who stands perversely munching, unthinkingly looking on.

I was eleven years old when I was first seized by the desire to pierce through my flesh. Freshly troubled by my permeability, I stood alone in the kitchen and dragged a steak knife gently across my wrist. Waves of pleasure swept over me. I didn't push through the barrier, but this marked the beginning of a rare indulgence, a morbid semi-masturbation.

A year later, emerging into teenhood, I showed my best friend my wrist. I was in love with her. Only she could understand. She looked at me meaningfully with her huge brown eyes. I was certain that she understood. A couple days later, she showed me hers. I had been careful, parallel lines carved slowly with a dull knife, but she had gone all the way, taking a razor to the flesh and slashing repeatedly. I was horrified. I begged her not to do it again. I told her I didn't want to lose her. Years later, long after our friendship collapsed (she'd discovered boys and pot, and I was still angrily in love with her) she told me she'd done it because she wanted me to think she was cool.

My next best friend was the real deal. By this time, word of cutting was sweeping across our Jr. High hallways, and gaining in popularity. Girls were constantly, covertly stealing glances at each other's wrists, and K. was rapidly rising to the fore as the most committed cutter. While other girls played at angst with a studded pyramid bracelet or two and the whisper of a suspicious scab, K.'s wrists were lined with endless studded, pyramid, rubber, cloth bracelets, nearly up to her elbows. On special days, the bracelets were replaced with gauze. She blamed her sleek black cat, Star, the scratcher, for the parade of welts on the front and back of her arms. Everyone was impressed. Their games of peek-a-boo simply couldn't compete.

A like-minded friend of hers regularly suggested cutting parties. I hated the idea and made sure to stay out of it. The act of cutting struck me as immensely private, even if a peep-show of scars and scabs inevitably ensued. To cut was to confront mortality head-on, to plunge oneself into the dream of dying. To gather a crowd of cutters, seemed to me, to make light of a very grave encounter. Communal cutting was nothing more than sexual play, another way of penetrating your partner, as if all the others weren't enough. It was, in a word, obscene.

In “Powers of Horror,” Julia Kristeva describes her concept of the abject as a sense of horror springing from an awareness of the permeability of bodily borders that imposes a confrontation with mortality. The most obvious, initial border between inside and outside is our skin. To infringe upon that boundary is to experience the most mundane, as well as most immediate, confrontation with mortality.

In his immensely popular multi-million dollar exhibition “Body Worlds,” Gunther Von Hagens, artist-anatomist, displays corpses that he preserves by a special process he invented called “plastination.” By replacing the fluids of a corpse with polymers, the body literally becomes plastic. Von Hagens claims that education, enlightenment, and a new kind of body pride are the aim of his exhibitions. Primarily interested in revealing the complexity of our anatomy, the corpses Von Hagens poses are always displayed without skin. We look into the body, vaguely aware that this oddly recognizable creature was once a living human.

When I walked through Body Worlds, nearly seven years ago, I had almost no emotional response to the bodies. They were fascinating, and certain poses struck me as ironic, or else in very poor taste, but I hardly felt that I was in the presence of human matter. It was not entirely unlike looking at Día de los Muertos candy skulls, except that I was indeed learning more about human anatomy. These bodies, skinless, plastic, and undeniably real, felt neither alive nor dead, and so I strolled on through with an easy curiosity. Without the skin, Kristeva's concept of abject did not apply. The boundary between the body and the world was entirely missing and I was entirely unaware of it. I saw only strange stiff muscles fantastically arranged.

Through his curatorial choices, Gunther Von Hagens attempts to infuse dynamism into his stiff bodies. From corpse-acrobats and corpses shooting hoops, corpses playing cards and corpses on horseback, corpses dancing and corpses performing CPR on each other (the man has a sense of humor), Hagens attempts to animate his skinless plastics. As time goes on, he grows bolder, increasingly committed to rousing his audience, to making his indelible mark and establishing himself and his bodies as immortal. A more recent tactic has been to unveil a rather sensual set. A female corpse sits on a swing, her head cocked coyly to one side, one arm up and both legs suggestively spread. The crowning jewels, however, are the fornicating corpses. Even the most sober onlooker (and I like to flatter myself that I am one) might have a strong reaction to these. (I do.)

Why do these do the trick, when all others may intrigue our minds, may turn us on to an eerie disconnect between the facts and materials before us and the strange quietness of our bodies in response to the dead propped up before us? Sex, which is inherently generative, is superimposed onto bodies which have no shred of life left in them and lie fixed, unable even to continue the cyclical organic live process of decay. And of course, there is the question of borders. In the act of sexual penetration, we permeate our border, but not entirely. Our skins hold us in, and whatever passes between is mediated by this final, though delicate, veil between the internal and external. To display skinless bodies fornicating is to suddenly snap the viewer into the awareness of missing skin, the protective border completely gone. It is to layer exposure upon the ultimate exposure. Their frozen expressions of ecstasy only destabilize us more. Should we be aroused by these corpses, thus posed? Can we help but be? This complete conflation of sex and death is startling.

Everything about “Body Worlds” is, in the bluntest sense of the word, showy. Skin is peeled back in order to show us the order of our insides. Corpses are placed in the most dramatic and titillating poses. And the many that choose to donate their bodies to Gunther Von Hagens presumably have a deep desire to be eternally on display.

While Gunther Von Hagens' corpses are peeled, the corpses in Andres Serrano's photography series, “The Morgue,” are elegantly unwrapped. Each body is carefully shrouded in fabric; any face on view is partially obscured to conceal identity and partially revealed to ignite our imaginations, or leave us with the yearning to see more. The compositions employ a classical approach evocative of Italian baroque painting. Those painters used dramatic light and shadow to animate and dramatize flesh, and drapery flowed with the movement of the living. Serrano uses both techniques, instead placing them in counterpoint to the motionless corpse. Under the influence of this contrast, we experience intensified stillness.

However, it is not always immediately clear when viewing this series of photographs that the subjects are dead. There is a sense that we are looking into something private, but without the knowledge of the series title and the captions to the photographs, it would not feel so different from peering in at a sleeping stranger. The skin gives the viewer the necessary cue. There are subtle variations in the color of the flesh, with grey, purple, tawny hues emerging, mauve lips and fingernails, and hints of dull cranberry where blood has pooled beneath the surface. The most direct signifier, used sparingly, is split skin: static gashes where both skin and blood have settled, and indentations and punctures that lead into deeper darkness. These demonstrate a border which cannot regenerate, that remains only because it was left behind.

Gently, we apprehend the dead, so delicately arranged, so recognizably once alive. Serrano conveys a deference to the deceased through his sensitive deliberation over which fragment of the body can be seen, and which should remain under wraps. Unlike Von Hagens' splayed corpses cartwheeling across the museum floor with screaming open mouths, Serrano's dead are still sleepers, quiet and composed for their final viewing.

II. SHELL

In the Jewish funerary tradition, there is no final viewing. The corpse is considered a husk without the human soul to animate it, the body merely a shell, base flesh, become incapable of elevating itself through the mitzvot. The flesh has had its day, and will now render anyone who handles it, or anything it touches, ritually impure. The more quickly it is dealt with and put away properly, the better. Regardless of background, many who view their dear departed quickly conclude that it's not him, it's not her anymore. The empty body that remains is a vulgar echo of who and what that person once was. Within a Jewish context, shrouding the body and leaving the casket closed is the surest way to honor the memory of the dead. We are meant to recall their living form, rather than a searing image of a lifeless corpse. But truly, the vulgarity of dead flesh takes this further: displaying a body after death is not unlike parading nakedness in life. Exposing dead flesh is obscene.

There is, nonetheless, in many of us, a deep longing to look at the body. Call it “closure,” call it “saying goodbye,” the desire to “see for ourselves” bespeaks our ingrained attachment to materiality. Even though I knew my grandmother was dead, even though I knew that the body in the pine coffin was her body but no longer my grandmother herself, I felt an overwhelming sense of relief when they pulled back the white shroud over her face and I saw the forever familiar shape of her long nostrils and thin upper lip, now slack and exceedingly pasty. We were checking to make sure it was the right body, and until that moment, though my mind knew, my body didn't—couldn't.

To prepare the body for burial, Jews perform a tahara, a ritual purification of the body. The ritual consists of three parts: cleansing, purification, and dressing. Women perform this task for women, and men perform it for men. When we washed her, we were very careful not to pass anything over her body and to keep as much as her covered as we could. We worked swiftly and carefully, with dutiful focus. We only spoke for necessary logistics, or to recite prayers, or to ask her for forgiveness. She was a corpse the whole time. She was cold and heavy and I could see the discoloration beginning on one side of her face, on her backside, the blood stagnating, and yet I couldn't help, at times, feeling so tenderly towards her, towards it? Dead, almost sweetly it seemed (she was in really good shape, they told me, no complications at all), helpless, especially when I grasped her cold soft fingers and scraped underneath with a wooden rod to make sure they were clean. It felt so much like I had done, what seemed like a long time ago, with my grandmother when she was living and her nails grew long. I had to be gentle, otherwise she would wince and exclaim, you're grabbing the meat of my flesh with those nail clippers! But this time she couldn't tell us, so we had to take care ourselves, and we kept her as covered as we could. Then we dressed her all wrapped up in white, tied the knots, put her in the coffin, and closed the lid.

The first funeral I went to was a Catholic wake. I was seven or eight years old. The twins down the street -- it was their dad. He died on his motorcycle, black ice on the highway, and then there he was, motionless in the casket, his face powdered up something awful. I remember him sitting in his garage wearing a wife beater, a beer in hand, amidst hanging naked calendar girls. I wanted so badly to look at them, but I was afraid the others might see me looking, and Stephanie did. I was mortified but she was at ease, commenting on her father's quirks with admiration. I wonder now, how would he like to know that they put that much rouge on his cheeks for his final go around? It struck me then as terrible, false and overwrought, even when Stephanie put her little hand on his big hand and stood there staring down at her departed daddy, a stuffed painted marshmallow Pa.

Embalming is not required or commended by any religious doctrine, Jessica Mitford points out in “Behind the Formaldehyde Curtain.” It is largely an American practice, of dubious legality, for which we pay hundreds of millions of dollars. It is the unarticulated standard practice of most funeral homes when you hand the body over, making it very widespread in this country. Here, an English woman recounts her encounter with an American embalmed body:

I myself have attended only one funeral here—that of an elderly fellow worker of mine. After the service I could not understand why everyone was walking towards the coffin (sorry, I mean casket), but thought I had better follow the crowd. It shook me rigid to get there and find the casket open and poor old Oscar lying there in his brown tweed suit, wearing a suntan makeup and just the wrong shade of lipstick. If I had not been extremely fond of the old boy, I have a horrible feeling that I might have giggled. Then and there I decided that I could never face another American funeral-even dead.

This English woman contemplates with horror the possibility that she might giggle at a funeral. The laughing matter is, of course, the insipid aesthetic of the embalmer, imposed upon what was once a respectable man. Embalming may be particularly garish, and an open casket funeral does not necessitate such an overblown approach.

When I arrived at the ICU to visit my friend and her husband who had been lying in a coma for a week after their car accident, he was already dead. He had expired half an hour before I got there. I came in clueless, not understanding the horror with which the hospital attendant looked at me or why she stumbled over her words, not understanding why so much family was gathering so quickly, sitting so silently together, not understanding anything until I got to the room where he lay swollen and gone with L. by his side. During the Sikh funeral, he lay in the open casket. The swelling was gone, but the discoloration wasn't. Perhaps they had powdered him, it was hard to tell. He was so thin, wearing a dull blue button up he would have never worn in life, lacking all the verve that so characterized him. But this was his body, without any bells or whistles, and then they put him in the fire.

III. SELF

I have heard of beautiful wakes, wakes in Barcelona where the deceased maiden is propped up behind glass, arms folded across her chest, face perfectly painted and peaceful with flowers flowing out from everywhere. Perhaps a deceased maiden is always beautiful, youth and femininity still lingering on her skin. Perhaps one should take advantage of this last opportunity to be seen and to be beautiful. Belgian photographer Frieke Janssen plays upon this desire to capture the idealized self for one's end with her art photography service, “Your Last Shot.” She describes the service as such:

‘Your Last Shot’ is your very last portrait. A serene and fearless portrait that will be taken of you now and that one day will be used to remember you by on your grave. Why would you have someone else choose a picture for you that you would have untagged yourself from? Your ‘last portrait’ will be finished in porcelain, so that it actually can be used when the time has come. Meanwhile: have a great life.

The portraits are lovely, with soft, muted colors, and dignified, subtly glowing faces. This project is aesthetically very appealing, but its shameless encouragement of vanity is almost troubling. Janssen's frank approach to a culture of “untagging yourself”, her sober attitude toward death, and her flippant nod to living saves this from being tasteless. Her attention to color, shadow, and detail elevates the aesthetic from incessant Instagram throwaways to high glamor.

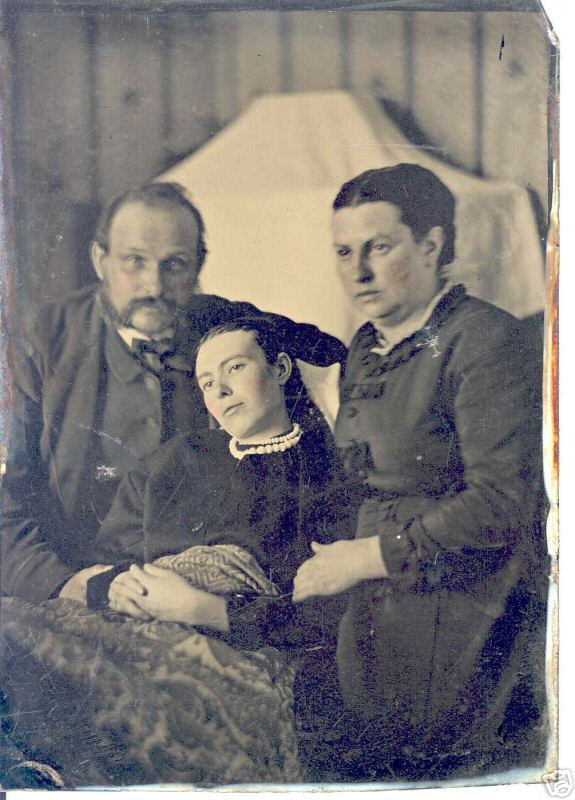

These portraits lie affectively nestled somewhere between post-mortem photography and funeral selfies. The post-mortem photograph, which emerged after the advent of photography, was a capture of the deceased, often very young, since child-mortality rates were high then. Frequently, the body was posed in a life-like fashion, sometimes with family standing by. These photos were meant to be keepsakes of the dead for the living. The dead are recognizable because they are in sharper focus than the living, who cannot help moving slightly during a long exposure.

Looking now upon these photos is almost uncanny. It is exceedingly strange in our current world to treat the dead as if they were living, even for a photograph. The enterprise might be considered delusional, calling forth certain uncomfortable scenes from the film Psycho. Janssen's growing series inverts this phenomenon, treating the living as if they were dead for the sake of vanity, projecting itself far into the future. The post-mortem photographs are a historical relic of a bygone era of photography, conveying an unfamiliar past. Janssen's employs an antiquated aesthetic, displacing her photographs in time so that they might be more palatable, so that the viewer might not notice that vanity was the most enduring part of it all.

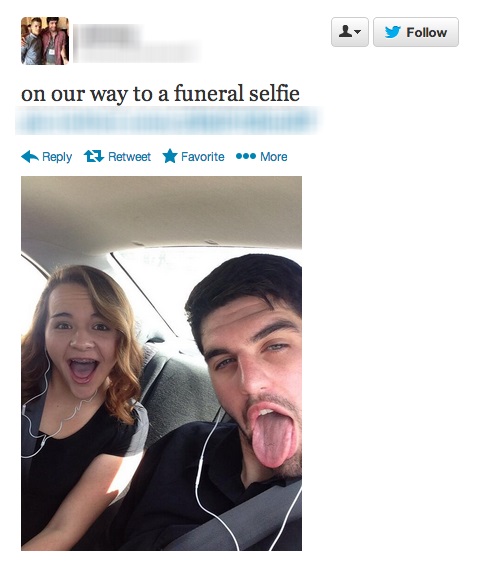

Meanwhile, funeral selfies are so wildly inappropriate, so inappropriately vain, and so much a product of contemporary meme culture that it's hard not to laugh at them. The methods Janssen uses to evade outrage are nowhere to be seen and funerary etiquette is blatantly disregarded. These selfies are appalling because of their glaring lack of deference to the dead or to the grieving living. They convey grief ironically, making light of a very somber affair. Unlike the English woman who regards her urge to laugh at a corpse at a funeral with horror, these photographer-models have no such scruples.

But wait, aren't these pouting posed young adults with styled hair the grief-stricken? If they seem self-obsessed to the point of ignorance of their surroundings, can we blame them? Grief is an all consuming emotional state in which the self supersedes the deceased. Grief dulls our attention to our surroundings as a result of intense internal pain. This pain seeks to ground itself in the presence of the deceased, but the deceased is gone, so the pain is largely self-directed, and self-pity may encircle the grief-stricken like a snake. How much grief, then, is appropriate to display? If the funeral selfie is too little, too light, then what is too much?

In “The Love Of My Life,” Cheryl Strayed chronicles her response to the death of her mother:

We aren’t supposed to want our mothers that way, with the pining intensity of sexual love, but I did, and if I couldn’t have her, I couldn’t have anything. [...] I did not deny. I did not get angry. I didn’t bargain, become depressed, or accept. I fucked. I sucked. Not my husband, but people I hardly knew, and in that I found a glimmer of relief. [...] With them, I was not in mourning; I wasn’t even me.

By denying herself everything, Strayed begins with a sense of affliction that we have come to expect from mourners. Self-affliction is, after all, the standard of many mourning traditions: wear black, no color, no music, no parties. Soon after, however, we learn that her emotional response is to fuck. This is not an emotional response, this is an act, one typically not associated with mourning except as a prohibition. Yet, sex is her coping mechanism for her grief, and therefore it is a mourning ritual of sorts. At the same time, sex is her escape from mourning, an escape from her self. She feels the need to negate herself, and she chooses to do so by amplifying her body. Having a lot sex with a lot of strangers and cheating on one's husband would usually be considered extremely selfish and self-obsessed behavior. In the case of Strayed, she mourns by escaping mourning, and she negates herself through self-indulgence.

I’m alive, I thought in that giddy, post-sex daze. [...] I didn’t stop to think: What if it had been my last day? Did I wish to be sucking the cock of an Actually Pretty Famous Drummer Guy? I didn’t think to ask that because I didn’t want to think. When I did think, I thought, I cannot continue to live without my mother.

Fixating on the problem of thinking, Strayed attempts to follow her thoughts. She reveals a circular pattern determined by the pain of her grief. The only thought she is capable of thinking is that she cannot live, and so she fucks in order to avoid thought, to force her body to overcome her mind. The body dictates “I'm alive” in the afterglow of sex, and this is the only moment in which the feeling of “alive” is free from the pain of “without her.” These brief, precious moments pave the way for “alive” to expand within her mind again, until it can get big enough for her to reclaim her self.