Lia Friedman

Plots, Puppets, and Petersburg

ISSUE 35 | DYNAMITE | DEC 2013

[Puppet theater] is….an anarchic art, subversive and untameable by nature, an art which is easier researched in police records than in theater chronicles, an art by which fate and spirit does not aspire to represent governments or civilizations, but prefers its own secret and demeaning stature in society, representing, more or less, the demons of that society and definitely not its institutions.-Peter Schumann, “The Radicality of the Puppet Theater”

In a small town in northern Vermont, a group of activist-artist-bakers are plotting the demise of American civil society. A year ago, a class I was in entertained a visitor from the Bread and Puppet Theater in Glover, Vermont. After a brief puppet demonstration, our visitor, a slight young woman, fielded questions from the class. Someone asked her what kind of change, ultimately, Bread and Puppet hopes to enact. “We aim to bring down the American government,” she replied in a brusque, even tone.

She wasn’t joking. In addition to baking bread and putting on elaborate weekly shows, Bread and Puppet aims to foment revolution. Puppets and politics form a natural pair—we often use the metaphor of the puppetmaster to voice suspicions about manipulation and coercion. But while the puppetmaster occupies the role of villain in our collective imagination, the puppets themselves possess undeniable power. As our visitor demonstrated how to perform with a puppet, she seemed to bend to its will, her identity subordinated to this inanimate thing. Puppeteering is a tedious, uncomfortable vocation: human physical needs are necessarily brushed aside for the visual impact that the papier-mâché object creates. Peter Schumann, the founder of Bread and Puppet, claims that the puppet possesses political, indeed almost mystical, force. “Puppet theater,” he writes, “is the theater of all means. Puppets and masks should be played in the street. They are louder than the traffic. They don’t teach problems, but they scream and dance and display life in its clearest terms. Puppet theater is of action rather than dialogue. The action is reduced to the simplest dance-like and specialized gestures... ” Here, Schumann hits upon the most exciting and sinister aspect of puppetry: the “theater of action” doesn't comment, it creates, transforms, speaks for itself. It is an artform teeming with potential energy.

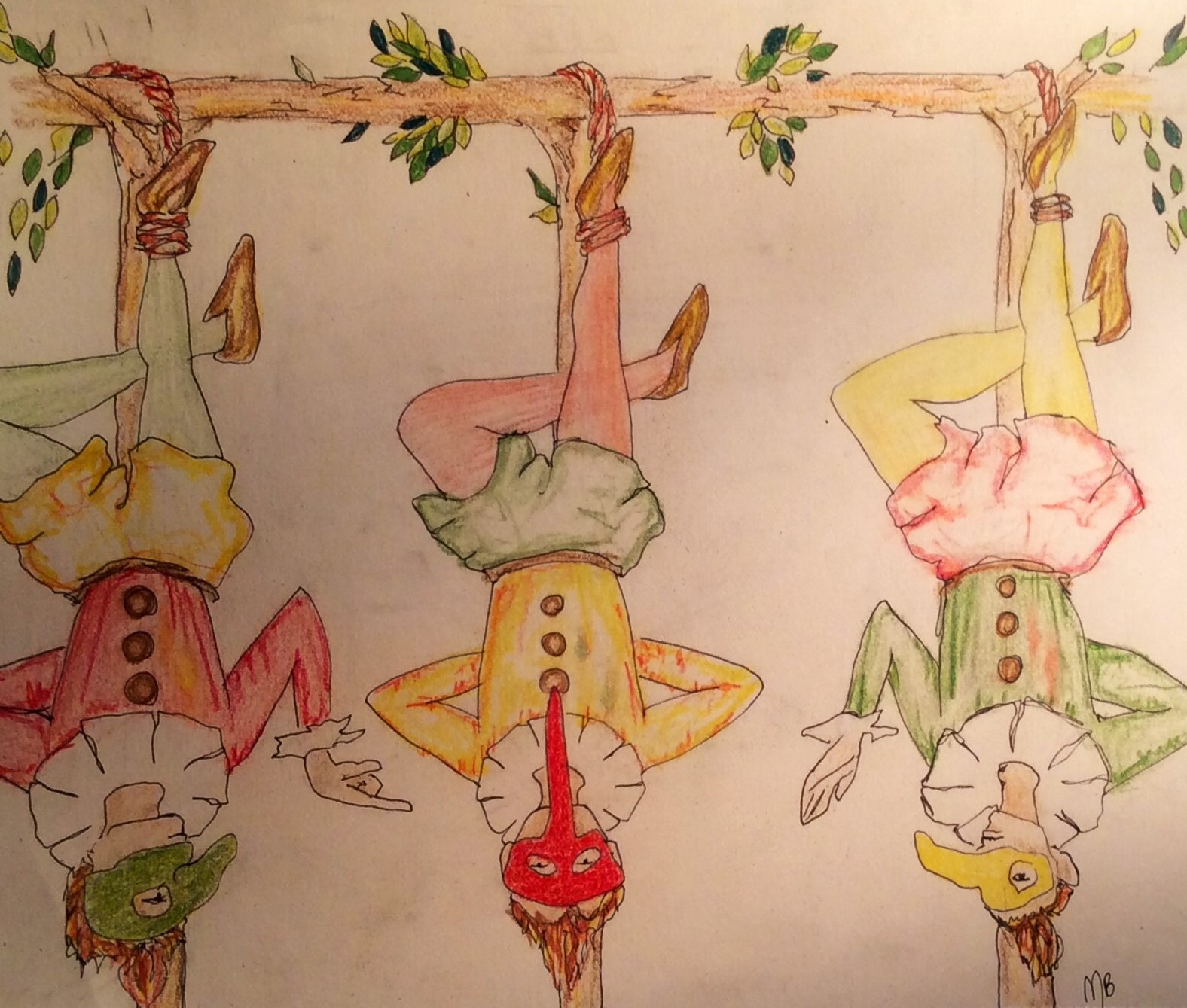

Illustration by Michelle Bentsman

RUSSIA

Which brings me to Russian terrorists.

The turbulent late years of the Russian empire produced not one but two novels about terrorist plots that abound in images of carnivalesque horror. Dostoevsky’s Demons (1873) and Andrei Bely’s Petersburg (1913, revised 1922 [!]) both dramatize the activities of radical terrorist groups. Members of terrorist cells engaged in secretly planned and spectacularly performed acts of violence, and both Dostoevsky and Bely employ theatrical imagery to represent the dual nature of terror, as a both private and public phenomenon. This theatricality ranges from Shakespearean allusions to acts of costuming and scripting to images of puppets and clowns.

Theater was part of the terrorist program in reality too. In order to “penetrate everywhere,” as Sergei Nechaev, prototype for the villain of Demons, mandated in his Catechism of a Revolutionary, members of revolutionary groups donned disguises, often creating multiple false identities and staging elaborate scenarios to carry out their schemes.

Not only does theatrical imagery appropriately describe terrorist activities, it also presents an apt metaphor for the nature of social and political control. For both Dostoevsky and Bely, the extent to which characters seek to manipulate one another parallels the tug-of-war for political influence. The popular folk puppet Petrushka and other features of the Russian balagan—the carnival sideshow or fairground booth—figure into both novels. In both novels, characters exert control over one another through acts of costuming and scripting. To this end, the metaphor of the puppet (and, naturally, the diabolical puppetmaster) occupies a central role in each novel’s artistic landscape—in both cases, fictionalized members of terrorist cells attempt to pull the strings from backstage. The novels’ highly conventional social worlds—worlds of masked balls, go-betweens, and drawing room scenes—can be seen as stages on which marionettes, compelled by forces unseen and offstage, operate. However, images of puppets contend with allusions to autonomous actors such as the highly trained improvisers of clown troupes (the commedia dell’arte). The coexistence of these different types of performers suggests a tension between a highly scripted and controlled scene and an unpredictable, chaotic world.

PUPPETS IN PETERSBURG

Reading Petersburg is no easy task. The action takes place on the eve of the 1905 Revolution, and largely follows the young Nikolai Apollonovich Ableukhov, son of senator Apollon Apollonovich, who has offered to assassinate his father for a terrorist group, and is called upon to fulfill his promise. The terrorist Dudkin gives him a bomb in a sardine tin, which, once activated, restricts the novel’s action to a tight timeframe. Meanwhile, Dudkin and his associate, the double agent Lippanchenko, destroy one another. The novel resists comprehension; it’s like catching flashes of faces through the masks at a costume ball. Case in point: A string of satirical news items opens the second chapter, describing the sudden appearance of a masked and cloaked figure in red on the streets of St. Petersburg in the autumn of 1905. The last of these items reads, “October 4. The population of suburb I. has fled because of the appearance of a red domino. A number of protests are being drafted. A squadron of Cossacks has been called in.” The strange and threatening image of the dancing red domino dominates Petersburg; the senator Apollon Apollonovich, one of the novel’s protagonists (and victim of the ill-fated terrorist plot), finds the red color of the costume “emblematic of the chaos that was leading Russia to its doom.” But it isn’t just the color of the domino which threatens social order; the domino also recalls traditional Russian puppet theater, a practice suggestive of fantasies of social upheaval. The carnival environment is one in which power structures are turned on their heads, and the appearance of a puppet (or is he a clown?—we’ll get to that) on the city streets undermines the propriety of the orderly prospects.

Images of puppets and clowns exploded onto the “high art” scene in Russia in the early 1900s. Modernist painters, writers, choreographers and playwrights drew on traditional Russian puppet theater, especially the wooden puppet theater balagan—which was a feature of carnivals, especially at Shrovetide festivals—and from the Italian commedia dell’arte tradition, which dates back to the 16th century, and introduced stock clown characters to the West. The most famous of the wooden puppets, the ubiquitous Russian folk puppet Petrushka, predates Peter the Great, is associated with folk culture and urban poor culture. He is raucous and rude, with a squeaking voice. Theater troupes brought commedia dell’arte to Russia in the mid-18th century during the reign of the Western-oriented monarchs, and it experienced a revival in the modernist period (late 19th to early 20th century), notably in the poetry and drama of Aleksandr Blok and Anna Ahkmatova. The masked ball was at the height of popularity in these years; explicit convention and overtly theatrical costumes were fashionable in both theaters and society. In the first decades of the 20th century, preeminent figures in the arts and theater scene Vsevolod Meyerhold and Alexandre Benois collaborated to bring to life productions that drew heavily from both the balagan and the commedia traditions. These productions were often associated with the Symbolist movement, such as Meyerhold’s 1906 production of Blok’s Balaganchik (often translated The Fairground Booth). The Symbolists began to conflate Petrushka with the sad clown Pierrot in the early 20th century. The most famous interpretation of Petrushka, Benois and Stravinsky’s 1911 ballet of the same name, fused elements of balagan with commedia.

“God was dead and the clowns had run amok,” declares J. Douglas Clayton, describing St. Petersburg itself in the first decade of the twentieth century as itself a kind of balagan. The transposition of the fairground booth to the urban center of St. Petersburg showed a fundamental shift in the attitude towards the city, an anxiety that was central to modern thought. The stock characters of the commedia dell’arte came to be seen as emblematic of the ambiguity and dislocation of modern life. The highly stylized masked figures that had no pretenses to realism supported the idea that the self is not immutable, but rather a kind of presentation; they also emphasized the distance between the real and the readily observable. The proliferation of masks in fin de siècle Petersburg instilled a profound cognitive dissonance in the city’s denizens. They aroused—and reflected—the suspicion that decent appearance might in fact mask sinister intent.

In a world in which the beautiful might no longer signify the good, it’s no wonder that several characters in Petersburg misinterpret the threat that the masked figure poses. If society is a masquerade, how do we know where true evil lies? We expect deception and illusion in the theater, but not necessarily on the streets. Apollon Apollonovich Ableukhov and the secondary character Sergei Sergeevich Likhutin (the man whom Nikolai Apollonovich cuckolds) are outraged by the domino’s ridiculous appearance and disruption of decorum, without recognizing the political threat its wearer actually poses: Apollon Apollonovich characterizes the domino as “some prankster with no sense of tact,” and Likhutin is far more incited by the domino’s preposterous behavior than anything else. If, as Clayton suggests, the very streets of Petersburg were transformed into balagan, the mere fact of theatrical dress and behavior must have posed a genuine threat to social order.

How does Bely identify his characters as puppets and clowns? Nikolai’s appearance and behavior often evoke Petrushka: the Russian folk puppet was traditionally garbed in red, with a pointed cap. Nikolai’s red domino suggests the red shirt; the pointed cap appears in the rhyme that Apollon Apollonovich makes up for his young son: “Noodle-doodle, dummy-wummy, little Kolya’s dancing/ On his head a dunce-cap wears, on a horse he’s prancing.” Nikolai’s movements are often jerky, evoking the movements of a marionette, and in fact, Apollon Apollonovich sees a “marionette in the mirrors instead of his son.” However, it’s not clear which Petrushka Nikolai is intended to recall: at timess, he evokes the crude Petrushka of the fairground booth, and at times, the tragic, put-upon Petrushka of the ballet, who is slave to a demanding wizard.

But Nikolai Apollonovich is not your run-of-the-mill Petrushka; his pale face (“Noble, trim, and pale of mien”) and his characterization as a “clumsy lover” are actually more reminiscent of the sad clown Pierrot (picture the solitary clown, dressed in white, with exaggerated tears). He also contains aspects of Harlequin, who is a buffoon in the Western tradition; this provides counterpoint to the wholly Russian tradition (Petrushka). Nikolai’s character contains aspects of buffoon, jester, and holy fool, rendering him morally and culturally ambiguous.

Nor is Nikolai the only character with puppet-like movements: “Sergei Sergeevich [Likhutin]’s legs jerked convulsively” during his failed suicide attempt, and earlier, Apollon Apollonovich reflects on the “the convulsive twitching of dancing legs and the blood red folds of clownish getups”; “the convulsive twitching of dancing legs made him think of a regrettable measure necessary for preventing crimes.” Apollon Apollonovich’s rumination makes explicit the parallel between the marionette and the punished political dissident; in 1905, Russia still sentenced convicted terrorists to death by hanging. The involuntary movements of the hanged criminals evoke the jerky movements of a puppet, controlled by the puppeteer figure—in this case, a hangman. Theater and politics uncannily converge on the stage of the scaffold.

WHO’S PULLING THE STRINGS AROUND HERE?

The political puppetry of Petersburg breaks with theatrical convention in one crucial respect. In the commedia and balagan-inspired productions of the early 20th century, the conceit of a diabolical puppetmaster or animating wizard represented a unified source of control over his inanimate puppets. This animating wizard is notably absent from Petersburg. The search for a center of power and directing principle proves fruitless: the bureaucratic center of power, the senator Apollon Apollonovich, can control neither his political career nor his personal life (he is forced into retirement and his wife has run off with an Italian). The descriptions of Nikolai, which present him both as Pierrot and Petrushka, put his agency into question: is he a passive puppet or a highly trained actor, skilled at improvisation, and therefore an autonomous, free agent?

Tension between the balagan tradition and commedia dell’arte articulates the difference between the controlled puppet and the skilled improviser and autonomous actor. Donald McManus describes the appearance of the Author in Blok’s Balaganchik as the intervention of “an artist who might prefer puppets, but is saddled with clowns who will not function in an orderly manner.” That is, while puppets and clown belong to the same milieu of the not quite human, one may be seen as a direct pawn, while the other resists authority. These categories are, of course, not absolute. However, in the context of Petersburg, the tension between Nikolai as Petrushka and Nikolai as a commedia dell’arte clown illustrates his vacillating submission and resistance to the plot in which he is implicated.

If Nikolai is a version of Petrushka, then who controls him, and what is the mechanism of control? Nikolai feels the tug of Dudkin, Lippanchenko and Morkovin’s strings, but none of these men truly represents a directing principle or center of control. Alexander Ivanovich Dudkin reminds Nikolai that the senator’s son volunteered himself for the assassination, but unlike Dostoevsky’s diabolical puppetmaster Pyotr Stepanovich Verkhovensky, Dudkin does not continue to coerce Nikolai; rather, he directs his murderous energies at Lippanchenko, and the political assassination attempt unravels. The revolutionaries and police agents do not occupy the main “stage” of action, which is dominated by the Ableukhovs and Likhutins. They attempt to pull strings behind the scenes, but, more often than not, fail to achieve their ends.

While Bely constructs a narrative that moves inexorably towards an apocalyptic finale, he exposes his protagonists as actors caught in a web of social, political and romantic intrigue that resembles farce. Terrorists act on religious notions of endtimes and martyrdom; the actions of Petersburg’s players, however, are not imbued with historical-apocalyptic significance; rather, they participate in a monstrous illusion. Neither entirely puppets nor clowns, they bungle nearly everything.

Ultimately, clowns and puppets serve as potent political metaphors for the subversive activities of anarchist and revolutionary groups. The ambiguities manifested in the phantasmagoria of live actors, puppets and puppetmasters spoke to the dislocation and decentralization that is the goal of revolution. I recently stumbled upon a subset of academic knowledge, which (to my delight) might be dubbed “clown theory.” In a study of clowning through the ages, McManus writes that the clown lends itself to political metaphor because “clown logic does not have an essential meaning other than to contradict the environment in which the clown appears.” In other words, the clown doesn’t mean; he only negates. He quotes Italian playwright Dario Fo, “The problem they invariably pose is—who’s in command, who’s the boss?” The aspect of improvisation that characterized commedia shows a theatrical world with neither author nor script; the highly conventionalized characters substitute “genuine” emotion with gesture or form, which might in fact disclose nothing. This is why, for instance, the Joker is such a successful villain—the prospect that his grin is just a grin. Unmotivated violence is scarier than violence with a comprehensive creation story. Russian terrorist groups of the early 20th century adopted the tactic of “bezmotivnyi”—unmotivated—terror: that is, they committed acts that were calculated to appear random, with no retaliatory principle.

THE SHOW’S NOT OVER UNTIL

Bely’s association of his characters with commedia and balagan undermines the suspense of the terrorist plot: the players in Petersburg are parts of an earthly, profane, and fundamentally repeatable plot, and even many different plots, the sum total of which is not a coherent narrative. Although the story moves towards the inevitable explosion of the bomb, the proliferation of carnival and clown scenarios predicts anticlimax—death is not the end in a puppet show.

Bread and Puppet’s Schumann is definitely on to something with his theory that puppet theater is somehow less sterile than other artforms. Puppets are not alive and cannot be killed, so the puppet show survives its own death—hence its mystical power. In perhaps his or her most powerful political ploy, the puppeteer effectively sacrifices him or herself in effigy. The human is effaced by the doll; paper and cardboard outlive flesh. Schumann, however, assigns a positive morality to his theater—puppet shows, in his view, are necessarily for good and not evil. In the Russian Orthodox tradition, this morality is almost entirely reversed—puppets are ambiguous, at best. Indeed, both puppets and clowns seem to be imbued with the capacity to inspire fear. Both display an eerily inscrutable face—expression without emotion. It’s no wonder that campfire horror stories are populated with dolls that come to life, or that many people experience a phobia of clowns (coulrophobia). The myth of puppet as associate of the devil endures; idols connote blasphemy.

Schumann wraps up his manifesto, “The tragedy of Modernism is its political and social failure, its inability to apply more than the formal discoveries to the historical situation…The question is…Are the arts interested in more than themselves? Can puppet theater be more than puppet theater by giving purpose and aggressivity back to the arts and make the gods’ voices yell as loud as they can yell?” In essence—what is puppet theater, released from the failures of modernism, prepared to do? For Schumann, puppets have the potential to redeem the historical failures of both art and politics, whereas in Petersburg, they represent the dislocation and ambiguity of modern society. When these puppets open their jaws, it isn’t the gods’ voices we hear.