Sam Dean

Kieselguhr’s Kid

ISSUE 35 | DYNAMITE | DEC 2013

Dynamite, from the get-go, got named like a Greek god, which rarely bodes well. Alfred Nobel took nitroglycerin, mixed it with German dirt and some water softener, and found that what had been a homicidally unstable explosive (his brother was blown up in his first factory) was now safely portable, and infinitely more useful. The name means “energy,” and your average stick has about a megajoule of it stored up inside, waiting to blow.

Dynamite was turned to weaponized ends soon after its invention. It’s hard to think of a more perfect (and perfectly ironic) tool of the capitalist’s own destruction. Swords were obsolete before the Dutch East India Company closed, and even the most money- blind managers have had the good sense not to run their bullet, and rifle, and gunpowder operations in the same town. Dynamite, on the other hand, comes ready-made and paid for by the company, lying around the workplace in easy-to-swipe stick form, and it can actually do some damage.

Dynamite quickly became an icon of workers’ struggle—in one of those nice historical coincidences, Nobel sold his first stick the same year that Marx published his first volume of Capital. And it didn’t hurt that American mines, where workers dealt with dynamite every day, were some of the worst places to work in the country.

Webb Traverse was a miner in the hard-rock, high-altitude mines west of the Continental Divide, clocking long shifts for three, three-fifty an hour in the years that, time-wise, weren’t all that long after the era when anyone with legs was jumping at silver and gold prospects in the same mountains, but life-wise might as well have been different countries altogether. Big companies from the east had already moved in, buying up the smaller mines and conglomerating, and the food chain had picked up a new tier of predator: instead of independent miners pulling as much as they could out of the rocks, Rockefellers and Guggenheims were pulling as much surplus-value as they could from each expendable man.

Webb had a family, a wife and four kids, and managed to get enough work so none of them starved or froze, but whenever he wasn’t working, Webb had picked up a habit of leaving the house and heading off to use the tools of his trade more recreationally. He’d lay a bundle of stolen sticks on the load-bearing joints, and Kaboom! There goes a railroad bridge, moving his personal ledger of value given and value destroyed a little closer to zero. Another night, he would creep under windowsills to set a time fuse, and Blammo! The assay office was gone, and the heavy-thumbed company weight man was pulped along with his sacks of slave-wage company scrip.

Rumors started that there was a kind of Union Avenger, or just a plain Anarchist, lurking in the hills, always out of sight of the mine officers and even the Pinkertons hired expressly for keeping hill-lurking to a minimum. They called him the Kieselguhr Kid, named after the German word for the absorbent earth that Nobel had figured out how to fill up with nitro. He roamed strapped with dynamite strapped in his bandoliers, and some said he had some kind of patented quick-light fuse striker that sparked as soon as he drew, and fuses timed out to the split second, and some said he could blast a bullet coming at him straight back at any unlucky company dicks who’d gotten the drop on him.

But as happened to most anarchists, or even the less-loony union men, no matter how much hope they had for the capital-cleansing effects of explosion, or from how far away they threw their anonymous cop-killing bombs, the Powers that Be caught wind of Webb, and maybe ID‘d him as the real- life Kieselguhr Kid, and set two hired killers on his tail. They found him, dragged him out into the desert, and tortured him to death.

This man, Webb, is the core central character of Thomas Pynchon’s Against the Day, one of his novels like V. and Gravity’s Rainbow, a freewheeling paranoid parallel picaresque history of cataclysmic world events. Or at least, as far as I’m concerned, he’s the core central character—these Pynchon novels turn the reader less into a guided guest through the minds of a certain set of characters, more into an overwhelmed Mr. Jones showing up at an orgy. You end up fixating on one, maybe two, of the bodies and minds that flash past, based on the predilections of the month you happen to be reading the book.

When I found Webb, the dynamiting Colorado patriarch whose kids spend the rest of the book (when you can even see them) noodling (mostly fucking, sometimes shooting) their way towards revenge, I was in a state of perfect Pynchonian receptivity for the story. I was spending the month in Colorado with my grandma, at a farmhouse outside of Fort Collins. The trip was part help help-out-and-say-hi to the whole family out there (aunts, uncles, neighbors, the pet pigeon), and part family history research—my grandfather died in 1965, when my dad was a toddler, but there were old letters and papers, and I was curious.

My first night there, before I went to sleep and my grandma went to listen to late-night talk radio in bed, she gave me a newspaper clipping. The 100th anniversaries of two things I hadn’t heard about, the Colorado Labor Wars and the Ludlow Massacre, were coming up, and she said my great-great-grandfather, my dead grandpa’s grandpa, a guy named August Christian Hennebold, had been down there at the time, fighting on the Union side.

Even if you model yourself on an Encyclopedia Brown as a little kid, or think of yourself as the Elizabeth Bennett of your middle school class, you can always shrug that particular pretense off. This family stuff, even though it’s just as baseless, just as actually unrelated to yourself, gets under your skin. Which is funny, since I must have picked up the idea of ancestry being somehow significant from fiction itself—there was no sense of clan unity in my upbringing, no hereditary anythings to split up or argue over, and not much sense of shared history. Except, I remember being three years old, before I’d read many stories of fate and revenge, and I was terrified that my father was going to die, since I knew his had when he was also three. Maybe it’s just that we can’t really imagine stories, any stories, without imagining them happening to us, and the knowledge of heredity makes that feeling harder to shake.

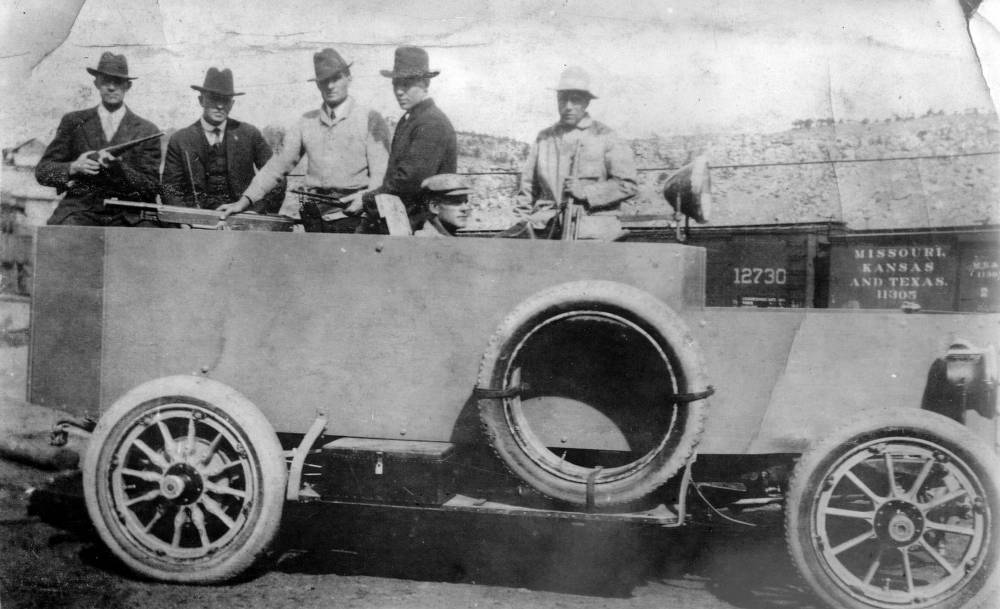

A hundred years ago, pretty much, from the summer of 1913 through to the spring of the next year, the Colorado National Guard laid siege to a tent town of striking miners and their families in Ludlow, Colorado, a Colorado Fuel & Iron coalmine camp town plugged into a canyon in the foothills west of Pueblo. One miserable night in April, 1914, after the strikers had spent one of the worst winters in memory in this semi-outdoors, the Guard and their scraggly auxiliary militia rode down on the camp, lit the tents on fire, and shot the strikers down with machine guns as they fled for their lives. The machine guns were mounted on armored cars, which the strikers had come to call “Death Specials.“ The leader of the camp, a man named Louis Tikas, was captured by the Guard, and while two men held him in place, the Guard commander broke a rifle butt over his head, then shot him.

The "Death Special."

A stunned railroad worker came by the next morning and found a pit, dug so that some of the miners and their families could sit somewhere for a little while without worrying that one of the stray bullets that the Guard kept peppering them with would maim them out of the blue. In the pit were four women and eleven children, suffocated and burnt by the fire they’d tried to flee.

You might have read about this in Howard Zinn’s People’s History of the United States, or heard the Woody Guthrie song about it, which is somehow made sadder by its disregard for much rhythm or rhyme. The press dubbed it a Massacre, since women and children had died, too. If it had just been strikers, they would have just been just a few more casualties of the ongoing war between labor and management in the mines of the American West. This war had been occasionally inflected with the manmade thunder of dynamite, for example in 1899, when the Coeur d’Alene strikers, in southern Idaho, had seized a train, the “Dynamite Express,” loaded it up with 4,000 pounds of dynamite and 400 angry miners, drove it straight (it’s hard to drive a train many other ways) to the main mill of one of the biggest mines in the area, and blew it sky-high. And there were hundreds of minor acts of explosive sabotage sprinkled around the Rockies for decades, whether perpetrated by earnest class warriors or by red-baiting agents provocateurs, as an excuse to string up (or more likely, shoot) more rabble-rousers with at least some pretense of guilt.

At Ludlow, things had taken on the color of class genocide, or at least class cleansing. So union men across the state mobilized, i.e. showed up with guns, at Trinidad and Walsenburg and Pueblo. Mourners at the mass funeral for the Massacred left the church, walked down the street, and grabbed arms and ammunition, distributed at the United Mine Workers of America headquarters. Over the course of the next ten days, anywhere from 69 (according to the corrupt Colorado government) to 199 (according to its corruptor, John D. Rockefeller Jr., a number with the sick echo of a retail pricetag) people, on both sides, were killed. Needless to say, the militiamen were, according to most historians, scum and mercenaries rounded up from any hole the mine owners could bear to look down (i.e. any hole), and the whole conflict had a collateral, or integral, maybe, element of racism, with most of the miners being recent(er) immigrants from the Balkans and Italy, while the militiamen tended to be the Irish and German and Scandinavian immigrants who had arrived a generation earlier, led by the infamous Swedish desperado scumbag, Karl Linderfelt, whose father was, unlikelily, Milwaukee’s first public librarian.

UMW strikers, on strike against CF&I, stand on railroad tracks close to a dead National Guardsman.

In the end, Woodrow Wilson sent in the federales, and both sides had to put down their guns in the face of their bigger guns. The workers didn’t get what they had set out to get at the beginning of the year-long strike, namely reforms for fair wages, an enforcement of the (Colorado Constitutionally-mandated) eight-hour workday, abolition of the company company-store system, and recognition of the union as a bargaining agent. They got none of it, after all that blood and shit. The conflict became a touchstone for the labor movement, and may have inspired Wilson’s support for a national 8-hour workday and Rockefeller’s aristocratic push to improve the conditions of his serf holdings, and the creation of a company union, but still: Linderfelt got a mild reprimand, and ended up dying in LA in 1957.

Linderfelt faces the camera.

If you’re not disgusted enough yet, here’s a snippet of Rockefeller’s defense of the “open shop”—using the same discourse-deforming rhetoric as the “right to work” laws in force in many states today—at a Congressional committee hearing on the strike on April 6, two weeks before the Massacre:

“These men have not expressed any dissatisfaction with their conditions. The records show that the conditions have been admirable … A strike has been imposed upon the company from the outside …

“There is just one thing that can be done to settle this strike, and that is to unionize the camps, and our interest in labor is so profound and we believe so sincerely that that interest demands that the camps shall be open camps, that we expect to stand by the officers at any cost.”

“And you will do that if it costs all your property and kills all your employees?”

“It is a great principle.”

In a break from reading Against the Day at my grandma’s house in Colorado, rooting for Webb of course, I started reading my grandfather’s secondhand memoir, a document that my grandmother had typed up based on stories he’d told her about his life. And I found a section about my grandpa’s grandpa, the guy down at Ludlow, my personal, ancestral Webb Traverse. That would make me the Kieselguhr Kid’s kid’s kid’s kid’s kid, I thought, or maybe, if it works more like a sarcastic hereditary title, just the Kieselguhr Kid myself.

Here’s what there was:

He could drink a fifth of whiskey and not be affected, but was still a hell-raiser. He taught himself to be a mining engineer, and became superintendent of the mining operation in Pueblo, CO. He was born in the 1840s in Alsace-Lorraine, moved to South America to avoid being drafted into the Kaiser’s army, and worked his way up to the US, learning languages and learning to be a blacksmith. He designed the largest chimney in the world, and when others were afraid to go up and build the very top, he did it himself.

Later, retired to a 40-acre farm in Bellflower, a part of LA that’s long since been paved over into South Central sprawl, he wore a tailcoat while poking around town, and was truly an egotist, as domineering as he was brilliant. He spoke Chinese, Portuguese, Spanish, and German fluently, and loved nothing more than to be called to act as an interpreter for some poor foreigner. He would say loudly, “I owe no one, I look anyone in the eye, I am my own master.”

He was the leader of the Ludlow Massacre in Trinidad and spoke of it proudly.

“Leader of the Ludlow Massacre in Trinidad and spoke of it proudly.” The syntax is vague enough that it’s hard to tell what that means. According to the Colorado Fuel & Iron archivist in Pueblo, who was nice enough to answer some of my emails, no chimney in Colorado has ever been the world’s largest, and the company has no record of an August Hennebold as an employee. He does show up, in an 1889 census, as working as a smelter in Pueblo. Which is to say that there’s a good chance much of this account is bullshit, and an equally good chance that August Christian was on the wrong side, rooting for the Guardsmen, admiring of Rockefeller, disdainful of the recently arrived Eastern and Southern European poor. The evidence is thin, but the CF&I archivist did say that someone who was some kind of “superintendent” would, in all likelihood, fall on the management side of this kind of fight.

It’s easy to imagine, in the sideways light of this, how August’s jumping at the chance to interpret for foreigners could be not an act of some expansive affection for mankind but pure condescension. And it’s not hard to think that his loud credo, that he was his own master, might have had the undertone of a nasty Objectivist snarl, and one that whitewashed the nature of bosses and the bossed around in the process. It’s not rare, even today, when anyone whose savings account grows annually can and does style himself a self-made man, to learn cruelty along the way from abject poverty to some kind of stability, and become proud of one’s accomplishments and spiteful towards the poor, the weak in body and mind and soul, the lazy vermin deserving of the treatment they get. It’s the intellectual underpinning of most of American politics on the right.

But to be that back then, just a few miles away from where people you’d met were being murdered for not wanting to be murdered a different way down in the mines, isn’t just self-involved and riled up and empty-headed, the way most Republicans seem today. It’s evil.

Even if he wasn’t, though, if he was on the side of the miners, there’s no telling if he was really out in the terror of those flaming tents, or on his way there when the flames caught, or meeting with his friends to argue the ethics of dynamiting a militia boxcar, or just sitting in his house somewhere back in Pueblo, riding out the strike, drinking beer and speaking German with his ex-yodeler Swiss wife, hoping his 23-year-old son, who volunteered for World War One three years later from Gunnison, a town back in the old silver- and gold-mining country of dynamite and Webb Traverse, wouldn’t get somehow shot.

I guess the fact that I had a great-great-grandpa within the general vicinity, either on the good side or the bad, doesn’t mean much, but this guy, August Christian, is practically the farthest-back relative I’ve ever heard of. It’s easier to sleep thinking of yourself, and your family, rising almost autocthonous from some muddy mass of Czechs and Irish and Polish immigrants arriving around about 1890, keeping their heads down anonymous in city tenements or the middle of nowhere, blank and mild, if occasionally alcoholic and conventionally racist, but overall too poor to have time to be truly vile, and too unsure to be evil. If I get down to it, this is a way of squaring the fact of being white in America, and educated, and well-connected, with the knowledge of what white, educated, well-connected people, historically, have done, and being able to come up feeling blameness. I’ve never asked a white Southerner what kind of hand-waving they do to deal with the same, or the truly and deeply rich, or even any kids of much more recent and obvious evils, the sons and daughters of SS officers, say, or Japanese soldiers who were in Nanking, all of whom I’ve surely met, and conversed with. I suspect theirs is much more sensible approach—they are not me, I am not them, who even likes their family—but I’ve had the luxury of quietly sympathizing with, and historically rooting for, everyone who I imagine has ever added some genes to what is now me. It seems like a small thing, and obvious, to think that there might be some real bad guys back there somewhere, but self-righteousness is a hard thing to even think about losing. His name, August, has ended up my middle name.

Against the Day slips into a kind of bemused okay-ness with the way everything falls out—some survivors from its fictional Colorado Coal Wars tilt down the slope of the continent to Southern California, others root their way up to the lawless Northwest, and one pair lands on the giddy Parisian Left Bank—and everyone seems happy to let the dynamite lie in storage. Which is just what happened in my story. My g-g-grandpa, and his son, an auto mechanic, and my just plain grandpa, a pacifist pilot and photographer, all moved with their families to LA. Like Linderfelt, the Massacrer himself.

The handy metaphor for how the big labor battles petered out around the same time is that dynamite, left to sit, separates like salad dressing. The nitro seeps out through the red (though just as likely brown, or black) waxed paper wrapper, and pools at the bottom of its box.

But really, it just got obsolete, and was old by the time of the Ludlow Massacre, too. There seems to be a certain scale, of machinery and explosive power and even population, at which revolution becomes so unwieldy a proposition that things seize up. The World War bred bigger bombs and bigger corporations, making dynamite seem dinky, even government seem dinky. Though it always was, in the mines, next to the bosses, and the superintendents who could be bought out, or the ones who even volunteered to cheer them on.

You always want more out of a story, don’t you? August exists in about two paragraphs of typewritten memoirs and two lines of a census document. If he was on the wrong side, I want to know who he shot, how he gloated, what silver pieces he received and whether he even thought about giving them back. Or if he wasn’t, there should be a story of compassion, or mixed feelings, or at least right-minded bluster at the back of a bar, boring his friends. There’s a feeling of slow erosion, a slight sway somewhere way down in the scaffolding, but probably nothing to get too worried about. In the long view, you know, every bang ends in a whimper.