Danya Lagos

Radical Hospitality

ISSUE 34 | BAIT AND SWITCH | NOV 2013

Hospitality, or the art of welcoming and caring for others, must be rescued from its current entanglement in stratification and alienation. Today’s approach to hospitality invites people into a hosting paradigm that emphasizes the host’s ability to provide “whole,” “fresh,” “slow,” and “local” food experiences. This school of entertainment emphasizes the artisanal, the crafted, and the shared enjoyment of these as an extension of the host’s character and ethical standing. It nods towards feel-good liberal politics with a concern over GMO labeling, fair trade (!!!) products, and a kinder, gentler way of slaughtering animals for our consumption. We have created entire industries devoted to certifications of all sorts, to verify precisely how humanely that leg of lamb was slaughtered, precisely how kosher the cheese is, and precisely how genetically unmodified those lentils are. Under this new technology of hospitality, the host is no longer one whose primary concern is to invite and attend to the other. The host has become a producer and hoarder of cultural capital, and guests have become mere instruments in this venture—even if they often serve as critics or evaluators. Large, open gatherings are increasingly replaced by smaller, rarer, highly exclusive dinner parties. Guests are carefully selected, excluded, and engaged. At best, they are partners in a cultural wealth-generating exchange. At worst, they are excluded altogether from our kitchens and dining rooms if they cannot contribute to or be willing, passive, assenting consumers of this performance of class.

It makes sense to want to know what is going into our bodies, and how it gets there. It makes sense to pay attention to how we eat our food. However, today’s dominant hosting ethic has been surrendered to an emerging bourgeois “food culture,” capitalist to the core, which often reifies inequalities in conditions and access to modes of production. We have remained satisfied to simply give space at our tables to various purchased nods towards conscience, while giving the mundane barbarisms of capital purchase over the rest. We have somehow learned all of the ways to use host-guest relationships to amass and exchange, but have conveniently ignored the opportunity to use our host-guest relationships to create revolution here and now. The dinner parties, the potlucks all full of people who went to the same type of college we did, have become a way in which our generation says “let them eat cake,” while we eat quinoa Anjou pear salad. For all of the self-aware demystification and borrowing of concepts from Sociology 101 that new marketers have brought into the everyday meal vernacular, we are only using these insights to make our meals socially “conscious,” rather than making them sites of social revolution. This transforms what ought to be an art of welcoming and caring into an art of alienation and exploitation—as the wealthy create exclusive technologies and venues through which to carry out their eco-bougie culinary fantasies. Settling for mere consciousness over revolution amidst conditions such as ours is a form of class violence in and of itself. Thus, it is necessary to intervene in the current conversation surrounding culture-driven hospitality, and to direct it to speak to revolutionary social goals that use food as a means to confront, rather than reproduce modes of capitalist domination—through a radical hospitality.

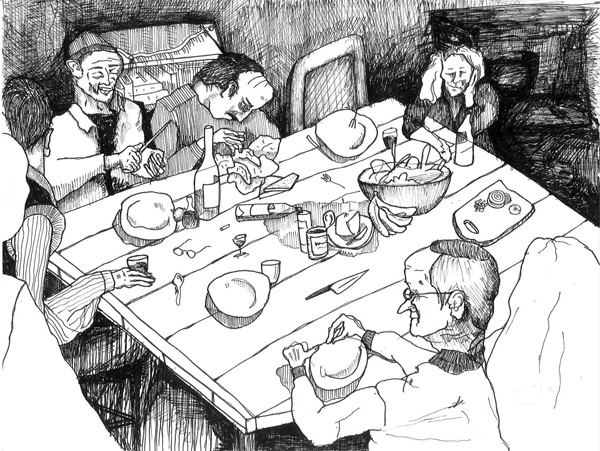

Illustration by Jon O'Neill

MANIFESTO

1. Radical Hospitality is a poorly defined term, thrown around most recently in art exhibitions at private university museums to advertise artist-directed meal installations, and among religious strategists who want to use it to attract more people to their communities. From here on, radical hospitality is more specifically defined as the act of transforming the art of welcoming and caring for others into a site of resistance to capitalist and patriarchal domination—precisely not the passive awareness or diplomatic form of negotiation with power brokers that has defined food culture up until now.

2. Radical Hospitality welcomes and attends to the stranger. Echoing the call “to each according to his needs,” Radical Hospitality commits to providing for all regardless of their position within our social networks. Receiving the stranger at our table is the ultimate form of symbolically and materially making space for the unconnected, the vagrant, and the traveler—and all individuals, as individuals. In the new configurations of togetherness that are taking hold, there is an opportunity for hospitality to open up new ways of sharing with new people. Thus, a radically hospitable community will realize what has previously only existed as a symbol in some traditions: always leave at least one actual chair for at least one actual stranger, and earnestly seek out strangers in the streets and on the internet to come fill it at every meal, in order to “let all who are hungry come and eat” here and now. Yet, in doing this, we must overcome tenacious sensibilities that prevent us from really turning the table into an open place for guests. Since we are not used to bringing strangers into our homes like this, we will develop a welcoming ritual for the stranger to ease the transition across the threshold and bring us into personal contact with people we do not know. For instance: A bowl and a washing cup can be passed around before eating, and all at the meal—host, familiar guests, and new unknown guests—can wash each other, while at the same time respecting each other’s bodily autonomy. This establishes an initial, physical experience of reciprocal care, in which all have contributed in some sense to the preparation for the meal by attending to each other. We could do anything, as long as we sharpen our power to transform strangers into guests.

3. Radical Hospitality builds solidarity amongst those who have been alienated from the means of production, and empowers all among them to combine efforts and resources towards the common interest of obtaining healthy food and the opportunity to care and be cared for by others. While bourgeois hosting tends to be a production, centered around one host or family and their ability to take on all the material and preparation burden (or a potluck-style show of inefficient glory-seeking dishes) a radical hospitality generalizes the responsibilities of preparing food in order to create communities of people who become one collective host. This maximizes the frequency and extent to which one can participate in hospitality. To this end, individuals living or working within reasonable walking distance ought to set up a common kitchen that is stocked, cooked in, and eaten in through a collective effort that strives to distribute and minimize the burden on its members while maximizing the use of the food and space available. For those who do not have the material resources to contribute at a basic monetary level, there should be other ways to belong to this collective such as giving time or expertise. While it is helpful to have a core of committed members to keep this operation going on a regular basis, these groups ought to also incorporate more informal ways of having people over. The groups could possibly focus on inviting and attending to people with particular similar needs and affinities who might not know other people in the group, but might have something else in common. We have the tools necessary to make them happen. Websites such as Meetup.com, CouchSurfer, and even those more directly geared towards sharing meals, are becoming a popular way for people to seek and extend invitations, and there is no reason why a new more radically-focused website could not be developed and popularized. Through such a website, people could create and publicize these collectives, opening up a way for people new to a city or just passing by, or who are looking for a particular set of people to break bread with, through a medium that is open to the majority of people today.

4. Radical Hospitality engages in intense forms of care during everyday and critical moments in peoples’ lives that are often delegated to paid service workers or religiously-based “hospitality committees.” Food is rightly seen as an expression of care. It nurtures the body and the soul, and is used frequently to mark celebrations, life cycles events, anniversaries—both good and bad. Meals that convey care are often delivered to people upon the birth of a child or the death of a loved one through churches and synagogues. However, these are not the only moments that are important in our lives. We are currently missing ways to care for others and be cared for during the moments of our lives that mean a lot to us now. How many times during the weeks or months after a break-up or a layoff, or even amidst the drudgery of most of our daily lives, could we have used our communities’ expressions of care through a home cooked meal and a table full of people to talk to, rather than a bartender? We could also use them to ease or commemorate moments such as illness, moving, academic or career success, etc. Furthermore, in an increasingly secularized age, these forms of care should also be extended to and sustained among those who do not necessarily belong to an organized religious community. The eating groups mentioned above can serve as a major source of these meals in various ways, including preparing certain favorite foods of the person who needs care, or bringing the food to the person on days in which they are homebound. Another way in which this can work is that groups of fellow survivors of events such as breakups, layoffs, and disease can form groups that meet regularly, like other support groups, but around the dinner table. This transforms the framework of hospitality even further, into a form of mutual aid in which people dealing with these forms of grief can be regular sources of venting, advice, and stir fry for as long as there is a need. By becoming hosts for each other, and preparing for guests that are going through very similar things that they are going through, hospitality can become a deeply transformative therapeutic process that takes the triteness of the golden rule and bends it towards a relational spiritual practice.

5. Radical Hospitality evaluates the merits of food based on a combination of its efficiency in feeding large amounts of people at low cost, as well as a basic, but not excessive or flashy concern with health and consumer environmentalism. It opposes glorifying or relying too closely upon vaguely effective uses of certification by companies that have built monopolies on assuring that our food is GMO free, organic, kosher l’mehadrin, or seeking to certify ourselves as cultural experts by always striving for the most exotic, the most seasoned, and the most unique dishes. Stews, soups, casseroles, and basic salads are particularly effective ways of maximizing resources and minimizing preparation time in order to create hearty meals for large groups, and can be gently seasoned without needing to replicate over-seasoned restaurant food. Starches such as potatoes and all sorts of noodles will not kill you, are relatively cheap to acquire, and make a great base for a wide variety of economic and filling meals. Frozen produce is basically as healthy as fresh produce, can be bought in bulk, and lasts longer. Legumes of all sorts can be soaked and cooked in advance in large quantities. The price of a Costco card can be split among large groups of people as long as the person whose face is on it is willing to go every now and then. We should take our cues from large families and co-ops that have found many ways to stretch dollars while keeping their members well-fed and happy.

6. Radical Hospitality invests food with renewed symbolism to commemorate and transmit emancipatory ideals. Throughout history, various traditions associate various foods with forms of transformative experiences, such as the eucharist, by which people seek communion with the flesh and blood of Christ, and the seder, which is orchestrated to bring the participant into a state of mind in which they see themselves as if they had personally been liberated from the chains of slavery. Radical hospitality encourages hosts and communities to build and tell stories of past triumphs and future goals around food, and to view guests as participants in their explanation and elaboration. Too often, our eating is rushed, unreflective, and when there is any conversation regarding the meal, it is generally reserved to talking about the quality or features of the food. Meals and menus can be themed not after the place of origin of the food or time of the year, but instead certain provocative questions or new ideas. There are times in which we should look into the silent meal as an opportunity for reflection. We need to start talking about how we are eating and why we are eating certain things in certain ways—why we sit in a reclining position at a certain time, why we are not eating foods from a certain producer or country, or why the oldest person at the table gets to pound back a shot of schnapps and yell “ALL HAIL COMRADE GEORGE!” at the end of the meal. These need to have stories, and it is okay to make them up as you go along.

7. Radical Hospitality takes into account that gender and sexuality are significant aspects in the experience of class struggle and domination, and combats the tendency of hosting to fall to women in a group even among purportedly egalitarian communities. It consciously enjoins men to split the burden of shopping, providing space, preparing, serving, and cleaning.

8. Radical Hospitality revives the community recipe book as a way of sharing and transmitting both the practical expertise associated with this approach to food, and also the history that can start to form as people come and go from these groups. These books should be bound in a manner that facilitates the constant adding and swapping of new ideas to make this all work, and should be the expression and source of a community’s values rather than other superficial forms of signaling and certification. Beyond containing recipes, these books can contain guides to the various rituals, guidelines, and values that develop, as well as basic how-to-guides that transmit wisdom on minimizing mess, inconvenience, and cost.

People will read this, and many will come up with all sorts of clever questions and rationalizations for why this cannot work: The stranger may smell like piss. The food may get repetitive and bland. The stranger once said something to me that offended me. It sounds like a lot of work. This is not how humans interact. Et cetera. The entire point here is that yes, all of these things are true, and there are many reasons for which they are true, and the current model in which we share food with others is part of the very messed up reason why these things are true. Those of us who want to be on the right side of the Versailles dining room walls must turn to the emancipatory potential we have at our disposal in everyday moments, since we do not possess the Super PACs, drones, or Williams & Sonoma pots that others do. Through the practice of sustained radical hospitality that pervades our hosting, our cooking, and our entertaining, we can weaponize the personal to pursue the political. Everyone’s gotta eat, after all.