Ethan Linck

On Singing

ISSUE 31 | STRATEGIES OF TOGETHERNESS | AUG 2013

My best friend in college grew up in Spokane, Washington, in a tidy suburb on the verge of a bluff overlooking a pocket of open space and airy ponderosa woods. He now lives as a Buddhist monastic at jungle-clad Wat Marp Jan monastery in Rayong, Thailand, and has taken precepts forbidding all forms of music. But for the three years I shared with him in Portland, Oregon, one thing was constant. When Nate wanted to get together with friends, he wanted us to sing.

Singing was de rigeur at any gathering and for any reason. Whether it was just to lure people over for peanut-sauce stir fry, or to perform some act of community catharsis during a time of crisis, he wanted us to sing together, rough, tuneless voices mixing with the pure and tunely. Mostly, he wanted to sing Josh Ritter, an earnest, beautiful and broad-faced songwriter from Moscow, Idaho, not far from his home. Ritter’s songwriting is often strikingly good but always nostalgic and without even the most modest whiff of shielding affect. All that earnestness made me uncomfortable, as if trying to harmonize with Nate and his friends was comparable to opening up about something deeply personal to my parents. It was wholesome, and unpretentious, at a time and place where those values were decidedly uncool. But I am contrary to a fault and I can’t pretend I didn’t fall for it.

The first time I heard Nate sing was the day we met, at the end of a long rutted dirt road in Yakima Indian Reservation in Washington state. It was 10 pm and a perfectly clear night that will remain etched in my memory for the rest my life, the Milky Way a smear of unfathomable complexity against the jet black of the night sky at altitude. We were due to crash for a few hours of sleep before rising at 2 or so for an alpine (read: uncivilized) start on Mount Adam’s Mazama glacier route, but that didn’t stop Nate from cajoling us into a rendition of Old Crow Medicine Show’s “Wagon Wheel” (what else? It was 2009 and we wore flannel) from our circle of pads and sleeping bags. Phil, tall and cantankerous and prone to biting on Nate’s attempts to bait him into sparring, shook his head in condescension or disgust. I remember shivering from something beyond the chill of the mountain night.

Throughout our upward passage we winced at the groans of shifting ice and crash of rockfall around us. We turned back well below the summit at the gaping maw of a crevasse with no easy crossing, but the sun was rising in eastern Washington and Nate and I couldn’t stop staring at its blood-drenched beauty despite our exhaustion. And so a friendship was formed, and a precedent set.

* * *

For the next few years, his voice began to underscore many of the significant events of my life, and in my more sentimental (or perhaps lucid) moods I consider it a pole star of sorts in deciding who and what exactly mattered to me. I have heard Nate sing hundreds of times, but I remember none of those as well as the songs that formed the soundtrack to a long spring road trip to southeastern Utah.

There is a romance to the Colorado Plateau that can only be found in a landscape imbued with literary significance, and for those of a certain philosophical leaning, it’s a requisite pilgrimage, a sort of inverse Manhattan or Paris you visit to somehow involve yourself in a storied human tradition while nonetheless finding only solitude and wind, geological eons frozen in red sedimentary rock under the baking sun. Silence, water, hope. Struggle, iron, volcanoes.1

In this corner of the earth the preeminent cultural voice and prophet is Edward Abbey, author of many fiction and a few non-fiction books that deal mostly with the desert southwest, and mostly with cantankerous, wilderness- and freedom-loving recluses with a fondness for nubile females. But he was a remarkably talented author and observer of natural world, and for those who love the writing and ideas and boundless spirit of Thoreau and Aldo Leopold, greats in what would become the ecocentric canon, he is a giant.

Since his death, his intellectual reproduction has been less literary (though there are or were a few scrappy magazines—The Canyon Country Zephyr, The Mountain Gazette—that come to mind) and more movement-based. Earth First!, the venerable radical environmentalist cell that has now sadly deteriorated into would-be-anarchists sniping at each other over the most politically-correct gender neutral pronoun, was directly inspired by his fictional renegades in The Monkey Wrench Gang. More directly yet, he is the looming figure overshadowing the dreams of anyone who has read his work and find themselves in southern Utah, a dog-eared copy of Desert Solitaire as mandatory as water and a gas tank over half full.

I think he would have liked that. Abbey thrived off embodying (in his writing and in person) cultural contradictions, and despite his education as a philosopher, he feigned disdain for the eastern intellectual markets that were often his largest audience. A writer who disliked writers, a strident environmentalist and NRA member, a great lover of women whose fictional women were the normative caricatures of a feminist’s nightmare.

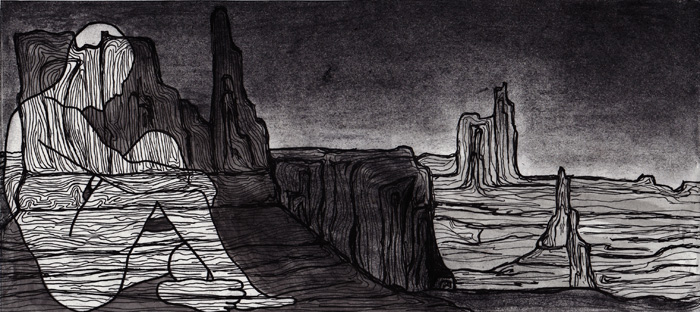

Illustration by Antonia Stringer

Abbey had women problems, and so did I. I was on the metaphorical red rocks with my then-girlfriend, and the trip would either consummate an irrevocable act of rebellion, driving between us a wedge of unspoken jealousy for my friendships with women outside of our relationship, or hey, the time apart would be good for us. The trip became a bone of contention. Staying was clearly impossible, and I told her so, but going also hurt, and I couldn’t make that clear. She stayed, and I left, cleft by competing strains of pain and excitement.

The introduction of Abbey’s most important and beautiful book, Desert Solitaire, contains many manifestos, none more cited than this passage:

I dream of a hard and brutal mysticism in which the naked self merges with a non-human world and yet somehow survives still intact, individual, separate. Paradox and bedrock. (6)

I copy these lines here as Nate always seemed more naked self than the rest of us. I could remember him at Subway, or the 24-hour coffee shop on industrial Powell Blvd., or depressed after a summer fling went awry, but I don’t. Like that night and morning on Mt. Adams, I remember him in wild, grand places. Above all, I remember his voice, its echo and the glow of fire against rimrock, the sweet sweet scent of juniper smoke.

One dreary March morning we left Portland and drove for the entire day into the bleakness of Idaho and shivered the night out in a parking lot by what was apparently the largest single-form sand dune in North America, though for fog and cloud its grandeur was lost on us. There was also a supermoon, a rare and beautiful event, and we had imagined arriving to the dune after it had risen and bathed the monolith in dazzling silver light. But it was overcast, and we couldn’t see that, either.

On the second day after breakfast in a diner where Osama Bin Laden was a very real and personal threat we drove on through the monochrome pyramidal sage and alkali desert of the eastern Great Basin. Through Salt Lake City, the religious majesty of the Wasatch front, its temple, and the surreal juxtaposition of countless billboards advertising plastic surgery. The smog below and the snow above.

When Nate was not driving, he’d sit in the back seat, and either meditate or sing to us, which was both bizarre and familiar.

At some point after 100 miles without a gas station or motel we reached the edge of the Colorado Plateau, emerging from a road parallel a tight stream bed in tight pine woods to a horizon both intensely flat and yet intensely deep, vertical in thousand-foot cliffs and mesas but ultimately wrought from a primitive palate of shapes versed only in the rectangular. Painted across it without respect for form, color jumping from cliff to plain to canyon, were bands of red and gray and yellow, crossed by undulating tidal shadows of cumulus against the desert sun. Vast beyond any textual gesture.

At one point I looked and saw I had missed a call from my girlfriend and felt the usual painful tightening of sinews within my chest but we left service and I had an excuse to ignore it.

By nightfall we were onto dirt roads cut with washes that themselves became roads in the beams of our headlights and the moon and our imaginations. The very idea of trying to find three other small people around a small car amid the shadows of junipers and pinyon pine began to seem arrogant and foolish and so instead we gave up. I fell asleep in the sand, wrapped in some sort of imitation Navajo-print blanket at the front of his car and looking for all the world as if I were on peyote. The next morning, though, we did reach our rendezvous, with Nate’s childhood friends Peter and Martin, and Peter’s girlfriend Ellie. Peter is thin, and long, and beautiful, and plays fiddle and dreams of starting a homestead in the Methow Valley of Washington state. Martin has a mustache and is boisterous and generally salty, and had driven from Durango. I could almost imagine him counting passing miles with six packs of Schlitz.2 With them, we plied its depths, following that most elegant of geological lines, the canyon, into the heart of a 7000’ mesa, a single fissure in Chenault’s3 metaphysically infinite landscape. As he writes somewhere, canyons are a vulvic answer to the peaks, and enforce a certain humility in foot travel. As you descend, your perspective by necessity narrows, producing an experience of a landscape garnered by intuition and interpretation of subtleties rather than seeing the whole damn thing at once. A thunderstorm miles away can produce cataclysmic deluges that roar into existence without warning, violently erasing life and all evidence of human passage.

Nate, of course, lugged his guitar, dangling from his pack by its headstock with no effort towards making it easy to hike or climb with.

He’d end up using it on our second day, having hiked and stemmed and scrambled far enough down the gulch despite it to catch a glimpse of the distant San Juan river, feeding the frustrated, iconic Colorado and beautiful like only water in the desert can be. Lauren and I became tired and left the group early. On our way back to camp, we became lost up the tresses of a side canyon, walking on autopilot until we faced with a sandstone wall at once so absolutely ordinary Lauren moved to climb it, and so damning in its implications I still imagine a cheesy symbolic cloud moving across the sun as we surveyed it.

I have been solidly lost twice and both times my thoughts have been similar—whatever I was missing most potently, imaginary headlines reporting my death or rescue, whether I had seen that particular rock before (the lichen! I swear we passed that hand-shaped patch of lichen!). But more than anything else, I’ve felt stupid, deeply and irredeemably stupid, each moment of lapsed attention a referendum on why I shouldn’t be wherever I was and how I had squandered something precious and man, life sure is beautiful when I’m not contemplating its slow end by desiccation and exposure. In this instance (I say as much to remind myself as anything), we were lucky, and somehow after several terrifying hours we extricated ourselves, or the maze let us go.

Everyone else had nice, safe days in a beautiful place. We ate dinner through the low-level haze of headaches from dehydration and altitude and emotional exhaustion, mastication causing spikes of pain like heat lightning. Then, our after-dinner social. Martin passed around a noxious cigar. There was a flask of whiskey. And like so many times before, Nate began to sing, but this time, it was as if he were in triplicate. Without encouragement or prompting Peter and Martin joined in, and word for word they sang songs they had memorized together on some far off evening. The songs were almost entirely Josh Ritter, of course, and often directly referenced the land and history and zeitgeist of the Idaho panhandle, near their mutual hometown of Spokane. To my ears, their singing seemed to root themselves in a mythology of origin and place.

Ritter’s song “Wings”—almost a whisper at first, set rolling arpeggios, then a wine-sweet chorus:

I stole a mule from Anthony—I helped Anne up upon it / and we rode to Coeur d’Alene—through Harrison and Wallace / they were blasting out the tunnels—making way for the light of learning / when Jesus comes a calling she said he’s coming round the mountain on a train

They sounded beautiful to us, and we were deeply grateful to be back.

* * *

That night we weathered a temperamental storm that shifted from dry snow to hail to sleet to the desert sun of midmorning. We climbed out to better weather, but something worse waiting.

Main Street in Moab, Utah was once a strip of rowdy bars that serviced the sort of men who worked in the region’s uranium mines, the town’s original raison d’être. It is now the sort of place where it’s hard to find honest-to-god instant coffee, where you can come back from simulated hardship and sit down to the opiate drip of a wireless connection and have food and drink of a quality unsurpassed for hundreds of miles. We, of course, lapped it up, at least until I checked my email, where the fragile human feelings that made the previous night’s music so wonderfully life-affirming cut sharply the other way.

My girlfriend—I should have answered that phone call. The week I had been away was not a salve to our wounds, but instead something septic. Those seeds of jealousy had sprouted into betrayal. To return again to Abbey, in a quote I can no longer source: Love implies anger.

There were two emails. The first, a nice note about how all our mutual suspicions about someone had been confirmed and she had done exactly the Right Thing and she missed me. The second, a nice note letting me know the first one was entirely a lie.

Black coffee was not a cure for shaking hands. But in a state where religious principles mandate gas station beer be capped at 3.2% alcohol by volume, you can still buy tequila, thank god. Nate did the honors. We left town behind and maneuvered to a vein of dirt in the slickrock badlands beyond the RVs and mountain bikers. We built a fire in the wash, and once again, the guitar came out. Tonight, Nate launched into his rendition of Ben Folds’ cover of the gangster rap classic “Bitches Ain’t Shit.” In stabler times, it’s a guaranteed sing-a-long killer, with its toxic sentiment and casual misogyny.

But then, damn it, I felt better.

* * *

Singing is something that is both egoless and egocentric, an act of selfless giving and exposure that is also deeply rewarding to human vanity, like any other creative art. I think Nate’s decision to commit to monastic life was a balance of these tendencies. To help others, he’d argue, he needed to do this for himself.

Last fall as Nate was deciding whether to take robes, there were a few more sing-a-longs, when Nate would drive down to Portland for the weekend. I think I ruined them, putting a bitter edge to my voice when we sang anything that touched thematically on loss or abandonment. “All you are is mean / and a liar / and pathetic / and alone in life and mean,” Taylor Swift would wail, and Nate was none of these things, but the rebuke seemed important. To my persistent shame, I think he noticed, too, looking at me helplessly and talking faster and forcing more jokes. And then one weekend, after one last visit, he left, and we stopped singing together at all.

We try to talk every few months. The last time, as I sat outside a noisy café on a street in San Francisco, bundled against the evening fog, and he sat on the porch of the monastery with jungle birds choiring at sunrise, he held an iPod camera at arm’s length. The video was crisp enough to see peach fuzz where he had shaved his eyebrows a few days before (what is sacrifice if not shaving your eyebrows?).

Nate had just been ordained as a full monk, at Wat Marp Jan. His parents flew out from Spokane for the ceremony. Because of his robes, his mother wasn’t allowed to hug him, a painful cultural distance remaining between them after over 8000 miles of travel. He wakes well before dawn and meditates for eight hours a day and sweeps and walks around the village for alms. I make coffee from a third-wave roaster with an aeropress, bike to work, and sequence mitochondrial DNA. I told him about my next move, my next job, and he told me he was going to be in Thailand for five years.

In many ways, despite my sense of the accelerating divergence of our lives, he doesn’t change. His sense of humor remains irrepressibly boisterous. We retain the ability to launch into hours-long discussion about attempting to wring meaning from life. He remains utterly honest about his failings, like how many servings of mango-sticky-rice he ate the last time he went to Bangkok (seven).

It can’t be the same, though. I wish we could get in a car together and start driving. Or walk down a distant arroyo, under cottonwoods and redrock bluffs and the reserved warmth of the mid-March sun. I wish I could hear him sing.

Singing: he hasn’t been entirely strict in adhering to his precepts. In a private moment, Nate said, his parents took out an iPod and played back an old video of him singing.

He told me it felt like a punch in the gut.

1From Neruda’s Canto XII, resonantly reproduced as the epigraph to Abbey’s Desert Solitaire.

2à la George Hayduke, ex-Green Beret and renowned saboteur in Abbey’s The Monkey Wrench Gang:

Out there in the open Southwest, he and his friends measured highway distances in per-capita six-packs of beer. L.A. to Phoenix, four six-packs, Tuscon to Flagstaff, three six packs…Time is relative, said Heraclitus a long time ago, and distance a function of velocity. Since the ultimate goal of transport technology is the annihilation of space, the compression of all Being into one pure point, it follows that six-packs help. (17)

3Dave Chenault writes a consistently excellent blog (bedrockandparadox.com, naturally) dealing with both his belief that Abbey’s work has “flown under the radar as one of the best extent examples to Nietsche’s problem of nihilism” and the relative merits of fat-tired bicycles.