Tessa Cheek

Building Paradise: Design Bibles and Garden Homes

ISSUE 22 | PARADISE | NOV 2012

These days water has gone from the field and the river, but floods in the city where apartments already drown for lack of space and light. It’s no surprise that the Garden of Eden has begun to take on a general appeal independent of its religious and spiritual promise. If the self is something of a material miracle, the dynamic product of the utmost in ephemeral brain activity, then what body, what soul, wouldn’t flourish in a garden? Isn’t the promise of Eden, of paradise, at least as rooted in the daily relation of self to physical surroundings as it is in the ideas of faith, innocence, and never having to wear pants?

A certain strain of popular design theory certainly seems to think so. The purveyors of this visual theology include Phaidon, Taschen, Architectural Digest, and many more—all publishers of a kind of bible.

Phaidon preaches the book of John (Pawson’s Plain Space), which speaks the simple word through large-format photographs that seem as devoted to a celadon sky at dusk as they are to Pawson’s white, movable-walled minimalism. Unencumbered landscapes abound in Plain Space, their visual power matched by what is perhaps the least ornate high-design cathedral on earth.

Taschen welcomes the ascension in Tree Houses. Fairy Tale Castles in the Air. In this whimsical account, “childhood fantasy meets grown-up savoir faire” through the quirky construction of the ultimate contemporary Eden. In these pages, our return to the innocence and awe of childhood is promised without the requisite sacrifice of the agency, the sexiness, which adulthood has allowed us.

Architectural Digest praises architect and design team Lococo and Carter’s “hush” aesthetic—a kind of white-on-white salvation from the political noise of their Washington, DC location. Its pages offer the reader a luminous depiction of a suburban Tudor Revival, an expansive light at the end of the tunnel.

Now, more than ever, luxury seems to mean less—less color, less clutter, less stuff in a big room, less room altogether. The critical reader could easily dismiss this apparent desire for visual peace, high-design’s sudden attention to naturalist minimalism, for capitalism’s latest clever evolution. Only a person with everything, or at least too much, could be so desperate to surround themselves with exquisite lack. That said, it’s worth asking what we find so pleasurable about looking at a picture of a beautiful home in a beautiful place. When we project ourselves into a space for fun, what we’re really investigating is a quiet kind of bodily want. Can a beautiful house be, more than a marker of wealth or status, an embodied teacher of a certain kind of happiness?

Materialism has been inarguably sullied by its association with immoderate, unsustainable consumption. Even so, a total rejection of the physical, far from absolving us of our greedy material sins, amounts to a kind of willful ignorance as dangerous as it is bland. It is not by rejecting but rather by critically engaging our desire to be surrounded by beautiful structures and environments that we recognize the complex, potentially constructive, communicative power of the physical.

As Yung Ho Chang, Beijing’s celebrated architect, demonstrates in his most recent exhibition “Material-ism,” architecture is, at its best, an exercise in “designing the experiential among spatial-temporal buildings and urban spaces.” It should be no surprise, Yung argues in his retrospective, that material realities of space so define even the subtlest aspects of our material selves. When we finger the glossy pages of our most recent Architectural Digest, or sneak glances at an un-purchased Phaidon monograph, we also whisper to ourselves: anyone would be happy living in this place. This whisper might be the most basic description of paradise available across time and culture.

The fall follows shortly thereafter. This place, that beautiful house, is rarely affordable for any of us and it is never accessible to everyone. At 10rmb (just over a U.S. dollar) Yung’s exhibition is by no means unaffordable and many of his buildings are open to the public. Despite this, his thoughtful installation registers as a whirlwind whiff of an otherwise hermetic experience, a story told in a language only degree-bearing architects speak. Exclusion from beautiful spaces and from the material lessons they seem able to teach us hinges on nothing less material than taste, which although it may be bought, may also be built. If we approach ownership as, at root, a kind of knowing or familiarity, it may be feasible to associate ownership with the purchasing of land, materials, and know-how in the production of a house. At the same time, this account of ownership seems pretty paltry when we hold it up to the understanding which comes with making—with building and designing a house, with cleaning its nooks and crannies and replacing, over the course of many years, its various rubbed-raw components. This is another way of saying that when it comes to collectively establishing the value of cold hard cash, paradise is political and houses are too.

At some level we already know that a house does not have to be expensive, or environmentally thoughtless, to be a teacher of happiness, to be beautiful, or desirable. Increasingly, the preachers of built paradises are speaking of houses that surprise us and leave us curious, houses that challenge our conceptions of interior and exterior, self and other, and which whisper of an emergent Eden already hovering not just in our kitchens and back yards, but also in our shared homes—our streets and parks.

Approaching a house as performance art meets sculpture, artist Theaster Gates has started Rebuild Foundation, a multi-city project born out of his first endeavor—a home for himself turned cultural center and archive on Dorchester Avenue on Chicago’s South Side. Gathered in the beautiful houses rebuilt by Gates are artist’s studios, cinemas, libraries, community kitchens, and daycares. Many of the same aesthetics that govern architecture and design publishing are still at play in the formulation and presentation of Gates’s projects. The very political idea that anyone could be happy in these homes retains power over their structure and lends weight to their constellated elegance. What distinguishes a “Gates-designed house” from many of those featured in Architectural Digest and elsewhere is that their desirability, their beauty, arises explicitly in relation to their occupants and not in spite of them—as many images of stylish, immaculate, and unoccupied rooms imply. When we read AD or T Magazine, the often famous occupants of the featured homes hover, at worst, as a kind of threat to the delicious dream of happily passing our own days in their pictured rooms. At best, they enter the narrative almost as houses themselves. Having, however consciously, taken pleasure from imagining a life inside this other person’s rooms, we now imagine the possible pleasures of life inside their body and situation. This desire to inhabit even the most intimate physical spaces belonging to others—beginning with their kitchens, their bedrooms, their marvelously outfitted bathrooms, and culminating in their very body—plays a critical aesthetic and economic role in the design publishing world which we can simply refer to as “the preservation of a dream.” Generally, we cannot enter these houses and we certainly cannot open a miniature office trap door and enter the occupants themselves, but we can buy the book.

In contrast, a house repurposed and redesigned by Theaster Gates is, by design, a porous space. Its presentation explicitly invites us to stop on by, to spend time within, even to change and add to its physicality. We are further encouraged to empathize with its occupants by quite literally becoming one of them. The political shift here, and its effect on taste, is neither small nor unimportant. It is the difference between whispering “anyone would be happy in this place,” and saying “anyone is welcome to come and be happy here.”

This kind of radical inclusivity forces us to ask whether Gates’s take on a “house” bears enough similarity to the canonical object to retain the name. Houses indicate privacy just as our sense of Adam and Eve’s experience of paradise is inescapably conditioned by its belonging to them alone. It’s also worth acknowledging that we call the freestanding structure occupied by many families an apartment building, reserving the word ‘house’ for the physical container of a single-family unit. The danger of ignoring the power of the physical is massively tied up in the definition of what we call a house—especially when offering the home as a kind of built paradise. If we are content with our inherited definition of space in this regard, then we are offering our tacit consent for the exclusion of many kinds of people, and many kinds of families, from paradise. We have only to remind ourselves of Adam’s patriarchal chest, bent under the weight of loneliness, to ask if in practice paradise is really so connected to ideas of privacy, seclusion and ownership. Is a mountain range less beautiful because it isn’t ours, or because a town has sprouted up in one of its valleys? The power of Theaster Gates’s project is that it says No, where other voices have said Yes.

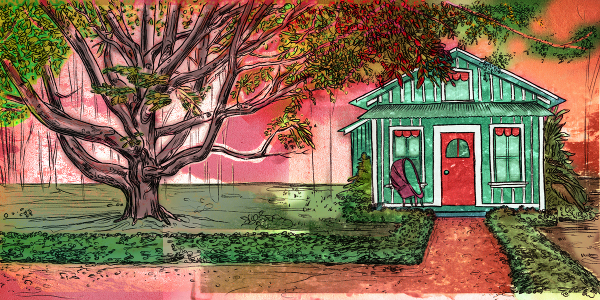

Illustration by Wesley Ryan Clapp

These questions of ownership, isolation and permeability find themselves radically carried forward in the growing popularity of “tiny houses,” which rather than including any and everyone seem to eject even their owners back into the wider world. Companies like Tumbleweed and Tiny Texas Houses (oh the irony) have built their sizable following on a sudden impulse towards living large in houses as small as 80 square feet. The upsides of these homes include, unsurprisingly, their tremendous aesthetic appeal. Online blogs and videos celebrate the tiny house’s Spartan efficiency, its cozy loft bed and toy-ish kitchenette, all packaged in a veritable gingerbread exterior. But tiny houses are not just for the quaint at heart: brutally (post)modern glass and steel walled constructions are increasingly popular options. The linking theme here is of a different aesthetic quality altogether. Many tiny homes are portable, several are built on trailer beds, and nearly all of them seem to be set down amidst shockingly lovely rural landscapes. The idea of the tiny house is not to force its occupants into a circumscribed living space; much the opposite. The benefits of the tiny house are often touted by the outdoorsy, those who want the structural nature of their home to question and critique its status as an ideal, everyday living space for human beings. If we extend our definition of home to include the outdoors, as some city-folk do to their neighborhood and wider metropolis, then having a small house in a big landscape offers all the space we could ask for, becomes a recipe for paradise.

Then again, the tiny house’s rigid confines, affordability, and implicit reference to a kind of dark futurism conditioned by overpopulation and end-of-days environments have made it an ideal independent form for the emergent, edgy architect. The blog Design Boom catalogs high-design tiny houses which range from ultra-modern glass and steel cubes, to rustic cabanas, to tree houses, to the flamingo-legged Single Hauz, the strangest of all. Single Hauz is only a prototype, perversely modeled after a billboard, and designed for just one occupant. What sets this little hauz apart from its diminutive fellows is the thrust of its presentation. It is pictured looming stork-like in fields, rising from what appears to be the Amazon River, or clinging to the face of something very like the Grand Canyon. The Polish firm Front Architects, designers of Single Hauz, specifically note its aptitude for extreme locations and go on to describe the prototype as follows: “an idiosyncratic, small manifesto, an experimental proposal for a home/shelter for the young or old man of the contemporary Western World. Today, the married couple, long regarded as the most basic social unit, is ceasing to be the sole model for living, at least for a certain stage of life.”

Both the Single Hauz and the rebuildings of Theaster Gates advance radical structural answers to the contemporary conundrum of what constitutes the privacy and intimacy of the “family unit.” Both speak of the could-be and both find their way into existing grand narratives regarding the progression of “history.” Even so, I would argue, their visions of paradise could not be more dissimilar. Written in the haunting, almost prophetic, prose typical of a science fiction novel, the description of Single Hauz projects us into a future in which the confining structure of wedlock has ceased to be a fundamental way of life. The result, Single Hauz suggests, or maybe foreshadows, is a series of solitary paradises in which future Western Man lives tethered to the extreme earth only by a single steel rod and a set of stairs. Here paradise is configured, most basically, as the end of history being also, as structurally confirmed by Single Hauz, the end of community. The prophecy tells us that Man will come to an ideal position as total owner and sole occupant of his island home, and perhaps the island of the world in general. Is this Western Man envisioned as the last pioneer of earthly nostalgia? How does he make meaning of his days surrounded by such lovely, abstract, isolation, and does he gaze—through abundantly large windows—at the distant moon colonies that support humanity’s teeming remainder? However nihilistic, the desire to return to Adam’s primordial propriety over the garden is mostly clearly prophesied, billboard-style, through the fantasy of Single Hauz.

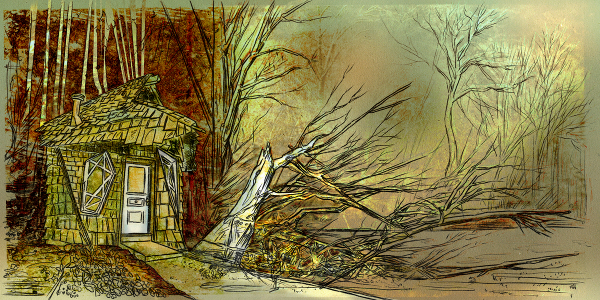

Illustration by Wesley Ryan Clapp

Gates’s cobbled-together projects are built by many, and variously trained, hands in existent properties with lingering and storied histories. Homes for an increasingly broad, rather than circumscribed, definition of the family, they are made to be lived, played and worked in by a range of people over the course of their overlapping and intertwined lives. Rebuild houses argue that we know paradise not by its unchangeability, but rather its evolution, its ability to offer a space of remembrance even as it nurtures a space for the new. There is no escape from time in such a house, no end to history and thus no material ownership possessing unassailable, eternal value. These houses disturb our fundamental, and ultimately misguided, assumption that paradise is part and parcel with sameness and do battle against the fear that were we to find ourselves in Eden we might go flirting with snakes out of sheer boredom. Paradise, these and other houses suggest, is not located in a garden miraculously instantiated for our sole use, nor in an expansive white room which cleans itself, but rather in the miraculous possibility and physicality of reciprocal care—that we will reap what we sow, with pleasure, and in turn be sown, with pleasure, world without end.