Avi Garelick

Beastly Flesh

ISSUE 21 | RAW MATERIALS | OCT 2012

Anyone who looks carefully at the source of meat, and at the tying up and slaughter of embodied creatures, should turn back from eating meat.

-Laws of Manu 5.49

It has become commonplace to approach the problem of eating animals with a heuristic of historical exceptionalism: our age is the most modern age, and our animals are the most ill-treated ever. The vegetarians of our day have very historically specific claims against eating meat, having to do with factory farms, genetically modified food, and other such horrors. If they would only reform the system, and kill animals like they used to, the modern vegetarian would be happy to eat them again. Granted, the modern horrors of the slaughterhouse are vast. But why should suffering, even the suffering of non-humans, be evaluated on a quantitative basis? Exactly how much less should a chicken or a cow suffer before our ethical equations say: you can eat that!

These days even meat-eaters want to know where their meat is coming from. Typically, it’s an issue of biopolitical management. Where do we keep all these living bodies, what can we feed them, do they get to go outside… The fact that some charnel houses are nicer than others elides a fundamental question: can we kill other animals in order to feed ourselves? What justifies it?

This question merits deeper consideration than investigative journalism will allow, unless you are satisfied with the answer “just as long as the creatures are allowed an hour on the grass every two days and get to eat non-GMO grass-derived feed products.”

Okay. The part of this essay that comes off as an angry rant in favor of uncompromising vegetarianism is over. I can actually imagine a handful of pretty compelling reasons to eat animals. One of the big ones is desire.

Just today, an interview with an actor appeared in the New York Times which handily illustrates this:

Q. You began eating meat after being a vegetarian for 26 years, but you sound as if your conversion were involuntary.

A. I never wanted meat, and then I started to have a sensation, a serious, undeniable, overwhelming hunger for meat that came upon me at 44. I was in the apartment alone, and someone was cooking a brisket down the hall. I left my apartment to go find the door that the smell was coming out of, and I found myself with my nose stuck in the crack of some stranger’s door just so I could smell their brisket.

I’ve been a vegetarian my entire life, and I’ve never seriously imagined the weight of this desire. But as above, testimonial evidence abounds. Some people refrain from meat until it haunts their dreams so persistently (hamburgers that hang from the ceiling!) that they cannot bear their abstinence any longer.

The Laws of Manu group meat eating with wine drinking and sex as things which are not wrong, “for this is how living beings engage in life, but disengagement yields great fruit” (5.56). In other words, vegetarianism is an important career move for an ascetic, but as an ethical imperative it is impossible.

Beastly flesh in the Hebrew Bible can be most deeply understood as an object of desire and satiation. Indeed, the paradigm of Israelite sacrifice takes the sacrificial beast as a shared object of lust for human beings and God. Many people, taking the binding of Isaac or the Yom Kippur scapegoat as their models, think of sacrifice as being fundamentally about the slaughter of an animal as substitution for the death of the sacrificial subject. But these stories are exceptions: only the sacrifices for atonement are about atonement. The majority of actual sacrifices—e.g., the thanksgiving offering, the well-being offering—are about splitting a meal with God.

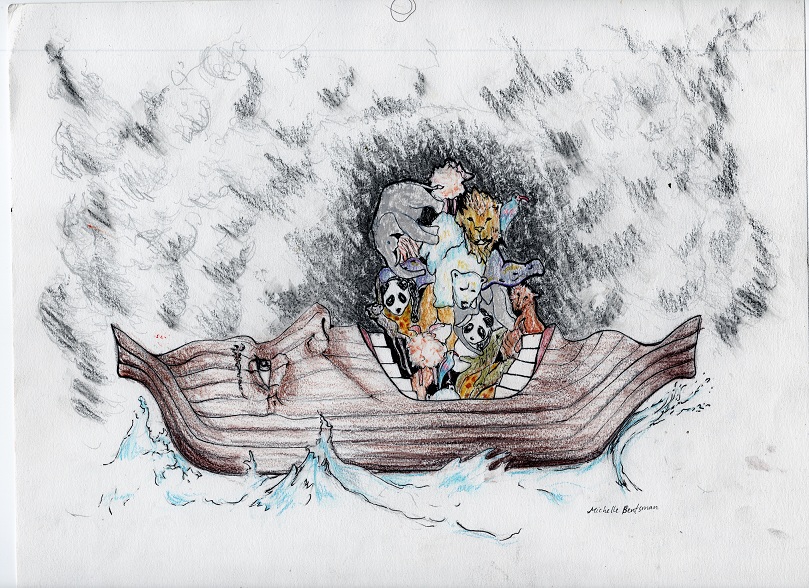

Abel, the fourth person on earth, is also the first person to imagine that God might want to partake of the fat of his flock. God readily affirms this perception. (See Genesis 4:4) Noah also readily intuits that, within the syntax of human/divine communication, an altar full of roasted meat means “Thanks so much for not drowning us! Please continue to be kind.” And in fact, after God smells this soothing smell (Genesis 8:21), He mellows out enough to a) vow not to utterly destroy humanity again, despite its endemic evil, and b) establish a new regime of law with regard to killing, which allows the killing and eating of animals for the first time. Presumably this permission is meant as a tactical deployment of violent energies, defusing the destructive forces with which the world had previously been awash (Genesis 6:11-12). The satiation that comes of slaking a lust for beastly flesh effectively sublimates humanity’s insane violent urges.

Illustration by Michelle Bentsman

The overpowering desire for meat produces a fascinatingly insoluble contradiction in social policy later in the Bible.

A man from the house of Israel who slaughters a bull, a lamb, or a goat in the camp or outside the camp, and did not bring it to the door of the tent of meeting to offer it as an offering to God at God’s tabernacle—it will be thought as blood to that man! He spilt blood! That man will be cut out from among his people. (Leviticus 17:3-4)

There, clearly stated, is the Biblical ideal—if you kill an animal, except in sacrifice, it’s murder. The only thing which justifies eating animals is the positive dimension gained by sharing your meal with the Lord. But this ideal only applies in the desert, an interstitial mythic space where the exigencies of material life and needs don’t apply.

The book of Deuteronomy is faced with the task of assimilating that ideal into real life in Israel.

Watch yourself, lest you offer your burnt offerings wherever you see fit. Only in the place which the Lord chooses, in one of your territories, there shall you offer your burnt offerings and do all that the Lord commands. But, according to every desire of your being you may kill and eat flesh with God’s blessing in all of your gates. … When the Lord your God enlarges your borders, as he told you, and you say ‘I will eat flesh!’, because it is the desire of your being to eat flesh, then according to every desire of your being you may eat flesh. Since the place which the Lord your God will choose to place his name is far from you, you may kill from your herds and flocks which the Lord gave you, and eat them in your gates, according to every desire of your being. … Only those of your holy things which you have, and your vows, should you take and bring to the place which the Lord will choose. (Deuteronomy 12:13-26, italics mine)

The realia underlying this text is that of a national territory which exceeds the scope of expedient travel. Also underlying the text is a strong motivation to establish a powerful cultic and political center for the nation. That’s “the place which the Lord will choose” (it ends up being Jerusalem). Deuteronomy is obsessed with the problem of idolatry, and believes that in order to curb idolatry the cult must be focused on a geographic center. Thus its emphasis on visiting the center at regular intervals, either for seasonal festivals or to bring in tithes and celebrate first fruits. So the center must combat the growth of other nexi of worship. As such, this text is struggling with two ideals. On one hand, as presented in Leviticus, is the interest in restricting animal killing and eating to sacrificial contexts. On the other hand is the interest in maintaining a strong cultic center. These ideals are brought into direct contradiction by the unavoidable real fact of appetite for meat, which cannot be repressed or ignored. People simply have to eat meat more than four times a year, it is the desire of their being. So, a choice: to allow makeshift, local centers of sacrifice, or to allow the profanation of animal-killing. The actual human desire for flesh creates this contradiction. In turn, this contradiction produces the secularization of meat—which you may eat just because you want it.

Another positive ideology of eating meat marks the killing as a kind of victory. Wendy Doniger says of eating in the Vedas:

Food was not neutral, and feeding was not regarded as a regrettable but necessary sacrifice of the other for one’s own survival. One’s cuisine was one’s adversary. Eating was the triumphant overcoming of the natural and social enemy, of those one hates and is hated by.

There are multiple dimensions to this agonistic world-view. One is a kind of glorious alignment with the order of nature. ‘Fish eat fish’ is the way of things, so to slaughter animals is to take your rightful place at the top. Social domination is described in the same terms. Natural and social hierarchy meet via a cultural continuum.

It also has cosmic and theological significance. The gods are imagined to have created the world by way of a primal sacrifice; human ritualists perpetuate it by regular sacrifice. The theological element tempers the gleeful brutality the naturalistic dimension might have on its own. “No one is a greater wrong-doer than the person who, without reverence to the gods and the ancestors, wishes to make his flesh grow by the flesh of others” (Manu 5.52).

Thus, within a stubbornly realist world-view in which every creature that participates in life really does so by killing, the only way to live with rectitude is to offer correct deference to the ultimate eaters, the gods.

Finally, killing possesses a regenerative power. In slaughtering a creature you imagine as your enemy, you gain political as well as digestive energy. Bakhtin talks a lot about this in his book on Rabelais, about how the earth upon which Abel was killed transforms his blood into fertility. (I am aware that this is the opposite of what is true in the text of the Bible itself.) He succinctly highlights the violence inherent in eating: “The kitchen and the battle meet and cross each other in the image of the rent body.” No feast can ever take place without a festal slaughter. In Rabelais’ peasant festivals, the doomed festal creature was symbolically connected to the clown-king, whose thrashing and uncrowning is followed by resurrection and fertility.

In certain French cities a custom was preserved almost to our time to lead a fatted ox through the streets during carnival season. … The ox was to be slaughtered, it was to be a carnivalesque victim. It was a king, a procreator, symbolizing the city’s fertility; at the same time, it was the sacrificial meat, to be chopped up for sausages and pates.

In this symbolic network, if meat corresponds to feast, vegetarianism corresponds to famine.

Anyway, this mode of thought obviously makes no sense today. Our feast-cows today are so dwarfed by our technological edifice that it would be quaint to imagine them as our vanquished enemies. But I do want to explore ways of making our eating into a kind of triumph. We have adversaries too, whose symbolic toppling can offer us political and digestive energy. To that extent, the problem of eating animals is a red herring as an ethical question. Our questions should really be about how we can organize our collective activity around eating as a site of battle with the dark powers of capitalism. Our kitchens are zones of politics, and eating should be a victorious celebration of the ways in which they have fought off domination and destruction.

Like Bakhtin, we can envision a kind of eating that is a “banquet for all the world”: “Man’s encounter with the world in the act of eating is joyful, triumphant; he triumphs over the world, devours it without being devoured himself. The limits between man and the world are erased, to man’s advantage.”

The Hypocrite Reader is free, but we publish some of the most fascinating writing on the internet. Our editors are volunteers and, until recently, so were our writers. During the 2020 coronavirus pandemic, we decided we needed to find a way to pay contributors for their work.

Help us pay writers (and our server bills) so we can keep this stuff coming. At that link, you can become a recurring backer on Patreon, where we offer thrilling rewards to our supporters. If you can't swing a monthly donation, you can also make a 1-time donation through our Ko-fi; even a few dollars helps!

The Hypocrite Reader operates without any kind of institutional support, and for the foreseeable future we plan to keep it that way. Your contributions are the only way we are able to keep doing what we do!

And if you'd like to read more of our useful, unexpected content, you can join our mailing list so that you'll hear from us when we publish.