Katy Burnett

Three Angels

ISSUE 96 | PROPHECIES | JAN 2021

In a despairing passage from his “Theses on the Philosophy of History,” Walter Benjamin describes a triumphal procession of rulers that step over the bodies of victims lying in the road. Looted cultural treasures are carried in the procession, and the advocate of human progress views them with “cautious detachment”—“for without exception the cultural treasures he surveys have an origin which he cannot contemplate without great horror.” To join the celebration, observers must set aside that horror and with it part of their own humanity.

Of course, this does not solve the problem of the horror itself, which remains vested in the spoils and which may quietly cling to those who have witnessed the procession. Though he probably wasn’t thinking of it, Benjamin’s image echoes the 1872 John Gast painting American Progress. A giant glowing white angel representing manifest destiny looms over fleeing indigenous people to the west. She is followed by bridges, trains, telegraph wires.

American Progress, John Gast (1872)

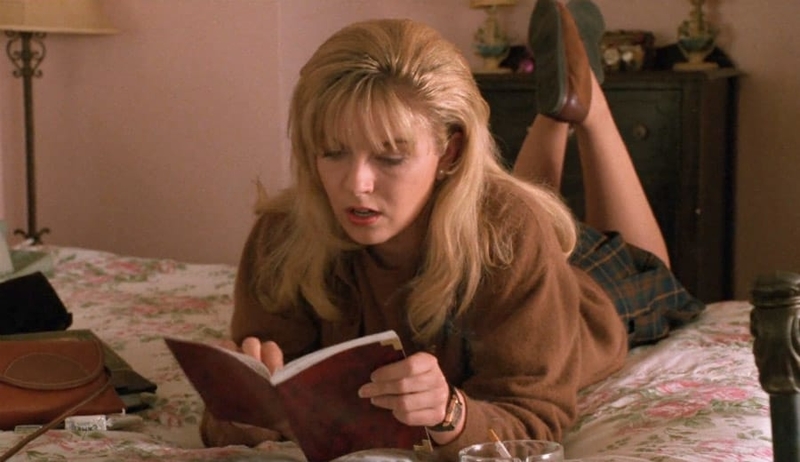

The events of Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me take place in Washington State a little over 100 years later, towards the beginning of the first Bush era. They recount the days leading up to Laura Palmer’s murder by her father, who is possessed by a spirit named Bob, on February 24th, 1989. Most viewers have already seen the TV series and know when they see Laura walking down a tree-lined street and gazing into the sky that she’s already dead. Though Fire Walk With Me does track Laura’s movements before her death with the focus of a conventional murder story, what differentiates it are the supernatural visitations unlocked in her life by the trauma of sexual violence.

Bob is one of several beings from the Black Lodge, an extra-dimensional place told of in the mythology of the local indigenous people. Both the movie and the TV series give us glimpses into the Lodge, usually through dreams. Some other Lodge inhabitants include a man named Mike with a close but confusing relationship to Bob, an old woman named Mrs. Chalfont and her grandson, the backwards-speaking Man from Another Place. Interestingly, these spirits—at best frightening, at worst violent—are all white. European settlement has not spared the spirit realm.

In an iconic dream sequence from the first season, Agent Cooper visits the Black Lodge and hears Mike recite a poem: “Through the darkness of future’s past / The magician longs to see / One chants out between two worlds / Fire, walk with me.” The final line reverberates. When Laura’s father confesses to her murder later on in the series, he reveals that his relationship with Bob dates back to his childhood, when Bob would ask him if he wanted to play with fire. He implies that Bob sexually abused him. In its recurrence, fire carries the same mystery as an untranslated word.

In the Twin Peaks universe, dreams are accepted with the same immediacy as the town’s material reality, but not everybody can see them or remember them. Having a dream feels like having a memory: that is, there’s a reported quality about it, not necessarily a sense that it’s happening in the present. And you can only share it with others after the fact. But dreams and visions come to Laura suddenly in the present of the film and we feel shock, terror, and confusion along with her.

Laura sees Lodge visitors when she’s between obligations, falling asleep, or staring into space in her room. She doesn’t have time or energy for these guests. They interrupt her work and leisure. Over time, she comes to realize that these encounters are leading her to the truth about Bob, and slowly begins to cultivate the apparitions and ask them questions about who they are.

It’s never clear what the Lodge spirits want from her. They speak in code or poetry. While human characters who deal with Lodge spirits repeat images like “fire” and “angels” to describe their experiences, the visual language of the Black Lodge itself is much more specific and concrete. The spirits are just as idiosyncratic as any of the townspeople, but when they speak it’s cryptic and without context or explanation, as though frustrated by the boundaries of their private language: creamed corn is repeatedly invoked, as is a formica tabletop and a ring. It’s difficult to read into the meaning of these specific objects or understand their power, or guess what they might mean for Laura.

The line between verifiable truth and metaphor grows fuzzy, as does the line between future and past. But no matter how “real” Laura’s visions are, their impact on her experience is the same in the end. Laura tries to record the things she sees in her diary. After her death, the record will turn into evidence, but even then it’s not clear what these visions mean or who they’re for, whether they’re flashbacks or premonitions or whether it’s wrong to use linear time to describe them at all.

The task of Benjamin’s strange, fragmentary 1940 essay is to challenge a certain received understanding of human progress which he associates with certain contemporary strains of Marxism. His characterization echoes the ideology of American progress, carried from before the time of John Gast’s angel to the present day, where it has matured into the shiny poptimism of late capitalism. Benjamin describes a faith in “the infinite perfectibility of mankind,” unbounded and automatic. He finds this “irresistible” forward march allows no opportunity for an expansive awareness of the present moment, let alone the past.

But, he goes on to explain, the past does return, whether we call it back consciously or not. Benjamin repeatedly uses words like “erupt” and “blast” to describe how the past interrupts the present. In contrast to a vision of history populated by “homogenous, empty time,” he proposes a history where time is “filled by the presence of the now.” The electric charge of the present moment is thus restored to moments from the past, each carrying their own idiosyncratic textures, oppressions, contradictions that guide them to return to us in their own time, even if their motives are beyond our understanding.

It is worth noting that Benjamin’s vision of nonlinear time echoes language used over the past century to describe our evolving understanding of individual trauma. Psychoanalyst D.W. Winnicott also abandons chronology in an attempt to heal patients paralyzed by fear. In a 1963 essay, he advances a hypothesis that fear of breakdown, although it may appear forward-looking, is actually fear of a breakdown that has already been experienced. The patient carries the breakdown within them but their fear renders them unable to access it intentionally. Winnicott writes, “The underlying agony is unthinkable.” If it cannot be thought, how can it be reached? The breakdown is like a radio station with the patient’s fear keeping it just out of range: it cannot be located on the dial, but bursts of transmission occasionally crackle through.

As a clinician, Winnicott’s work focuses on the individual rather than the culture surrounding her. The success of David Lynch’s TV series has as much to do with his loving portrait of small-town America as it does with its hidden darkness, and he grounds Laura in her town and its institutions. Twin Peaks is an imaginary place that draws energy from certain 1950s movie tropes: families headed by strong fathers, diner and roadhouse, a heavy preoccupation with high school, but underneath the sunny exterior of the town lurk domestic violence, addiction, and poverty. An air of timelessness conceals the historical specificity of the scene: Washington itself became a state on November 11th, 1889, less than 100 years before the film takes place. Nothing about Twin Peaks was inevitable.

Laura, a homecoming queen who volunteers with Meals on Wheels, looks like an organic outgrowth of this environment. Success in Twin Peaks is to be busy and to be liked, and Laura juggles friends and boyfriends, rushing between school, parties, and dinner with her parents. Every few scenes the camera glances at a clock. The banality of her activities contrasts with her Black Lodge encounters. There’s a timeless quality to those, too, but that’s what makes them mystifying and frightening. They don’t seem, directly, to refer to any specific time or place other than their own, and that makes them hard to interpret.

Laura remains mostly isolated in her visions; though her pain is evidence of what she sees, the people around her aren’t able to see or comprehend it either. In an after-school scene, Laura and her friend Donna are sprawled on couches in Donna’s living room. Donna wonders, “Do you think that if you were falling in space, that you would slow down after a while, or go faster and faster?” Laura replies, with the weariness of someone who knows, “Faster and faster. And for a long time you wouldn’t feel anything. And then you’d burst into fire. Forever. And the angels wouldn’t help you, because they’ve all gone away.” Laura’s vision is apocalyptic, but when she recounts it she just sounds tired and sad. It’s an image that doesn’t describe anything going on in the “real” world. While it seems like this is happening or has happened to Laura, it’s hard to know where she would locate herself in the story. Is she waiting to burst into flames, or is she already there? The film moves on without offering further interpretation.

Winnicott writes that to release fear of breakdown, a patient must, in the present moment, remember and fully experience the breakdown that has been deferred. This presents a challenge, for as he notes, “it is not possible to ‘remember’ something that has not yet happened, and this thing of the past has not happened yet because the patient was not there for it to happen to.” The traumatic event creates a gap in reality: if the patient had been there to experience the event, they would have been able to integrate it, and the event wouldn’t continue to surface in this troubled way. The patient and the event need to show up for one another at the correct time for this confusion to be resolved. But the moment of resolution is not guaranteed, and unless it occurs, the patient will go on anticipating the moment of breakdown without being able to reach it. The clinician’s task is to help arrange this meeting between the patient and the event and to bear witness.

The one person able to witness Laura’s suffering in a way that Laura herself recognizes is Margaret, the Log Lady. When Laura encounters her en route to the Roadhouse, Margaret puts her hand on Laura and speaks as though she’s channelling something: “When this kind of fire starts, it is very hard to put out. The tender boughs of innocence burn first, and the wind rises. And then all goodness is in jeopardy.” Laura starts crying, but she doesn’t pull away.

What is Margaret talking about? She is able to see or sense fire and allude to it. For a moment she and Laura are in the same place, and Laura doesn’t have to explain anything, and understanding exactly what happened is not important. They’re looking at some third thing together, the fire. Margaret sees Laura’s pain, smells the smoke, and gives her a kind of warning. But the warning shows respect, hope, and faith that Laura will be able to preserve her “goodness.” For a moment Laura feels the weight of the sadness she’d hoped perpetual motion might let her escape.

The only other moment of relief Laura experiences in the movie is once she’s already dead. Her murder finally comes as proof that what she’s seen is real, and as a release from doubt: she dies rather than allowing Bob to possess her. In the Black Lodge, when she finally knows that she’s died on her own terms, she cries with happiness. Agent Cooper is there and puts his hand on her shoulder. They stay that way, looking at Laura’s angel together. Unlike the rest of the eccentric Lodge crew, the angel is silent, still, and nondescript. She is a source of light, and maybe the only being in the film truly from the future: that is, abstract, without character or specific pain. Laura’s death allows her a release from suffering that she was not able to find during her life, and we are comforted to know that even though she’s dead she’s not alone.

But to be happy for Laura in death is to believe she had no other escape. While the TV series shows Laura’s connections to every part of the town, these connections only become visible once she is gone. In her presence all we can see is her suffering and the ways she numbs herself to avoid it. Instead of protecting her, the town of Twin Peaks has exploited Laura. By watching her disintegration, it feels like we as audience are also complicit in her death.

I’m reminded here of a third angel, Benjamin’s “angel of history,” also paralysed and watching history from a remove. “The angel would like to stay, awaken the dead, and make whole what has been smashed,” writes Benjamin later in “Theses on the Philosophy of History,” “but a storm is blowing from Paradise... The storm irresistibly propels him into the future to which his back is turned, while the pile of debris before him grows skyward.” This angel has the impulse to act, but lacks the power to do so. While our focus and the focus of the film is to save Laura, the forces that led to her abuse and murder—forces that killed Laura’s friend and working-class double Teresa Banks, led to her father’s own childhood abuse, and stretch back to the European settlement of the Pacific Northwest—would still be at large.

Benjamin refuses to accept the angel’s dilemma. He writes in defense of the past and present, trying almost hopelessly to push debris aside to create the hope and agency found only in the “time of the now.” The fragmented structure of the piece itself refuses linearity. Illustrations like the angel occasionally rise to the surface of the essay, but don’t stay long enough to be fully explained, leaving behind only a haunting outline. He’s training us to imagine past what we see, to make space by casting aside our impoverished projections of the future.

The ability to move outside of linear time, then, can be a gift: it’s a sensitivity to other timelines, and when wielded correctly may translate into expanded agency. But in the wrong setting gifts can carry a negative valence as well. In the constrained context of her life, Laura is set apart and overwhelmed by her visionary abilities. They’re diverted to her personal trauma, grown out of the rubble heap of the nuclear family and the American project. What Laura sees is what is already there, and because it’s tied to her own abuse all she can do is suffer. She finds no way before her death to address it directly.

The goal of psychoanalysis is to transform the painful aspect of experiences that are too much for the individual to understand. Winnicott hopes to remove the “defense organization” that keeps patients from recognizing undealt-with pain and allow them to move forward in their lives with agency, freeing them to participate more fully in society. Meeting a breakdown and emerging transfigured is a miracle, and the healing that occurs may thus contribute to the healing of others as well. While individuals can receive visions, Benjamin’s hoped-for revolution can only happen through the efforts of the collective. And a functioning collective is made up of individuals who care for one another and are able to share what they have seen.

Even after Laura’s death, the series focuses on finding some way to save her, as though rescuing her from death will redeem the entire town. But evil lingers around Twin Peaks with or without Laura. The conditions of American public and private life enabled her murder, and in the third season of the show, when the evil initiated in Twin Peaks has spread across the continent, Lynch hints that America itself cannot be redeemed.

The angel of history and Laura’s angel have shown up too late. The angel of American progress arrives only to spread genocide across the continent. These angels won’t save Laura or anyone else, but Benjamin’s time of the now still holds hope for a way forward. To restore the past to its singular fullness is to resurrect the oppressed, who are the “depository of historic knowledge.” We must “awaken the dead and make whole what has been smashed,” as Benjamin says of his angel of history. If visions and trauma have a purpose, it’s to reveal to us the openings in linear time where revolution may be possible.