Cat Pierro

Pitches for Poems

ISSUE 96 | PROPHECIES | JAN 2021

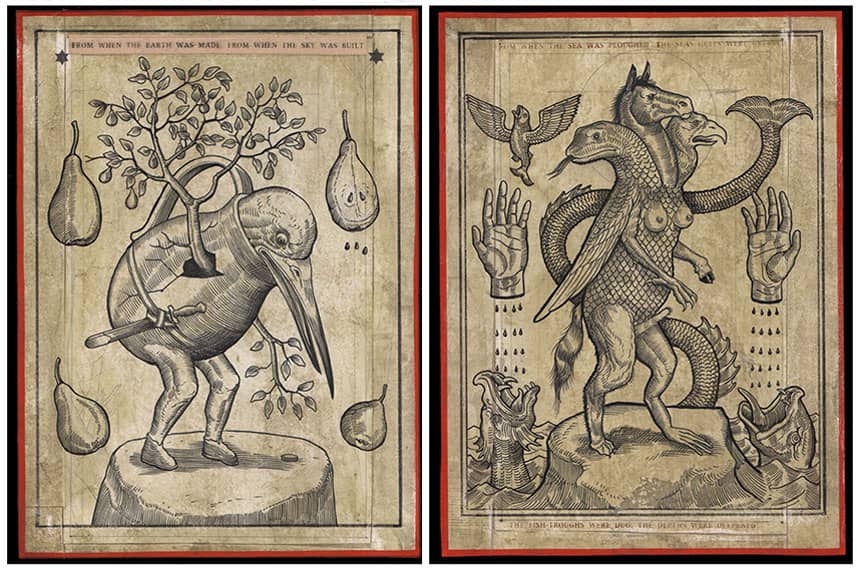

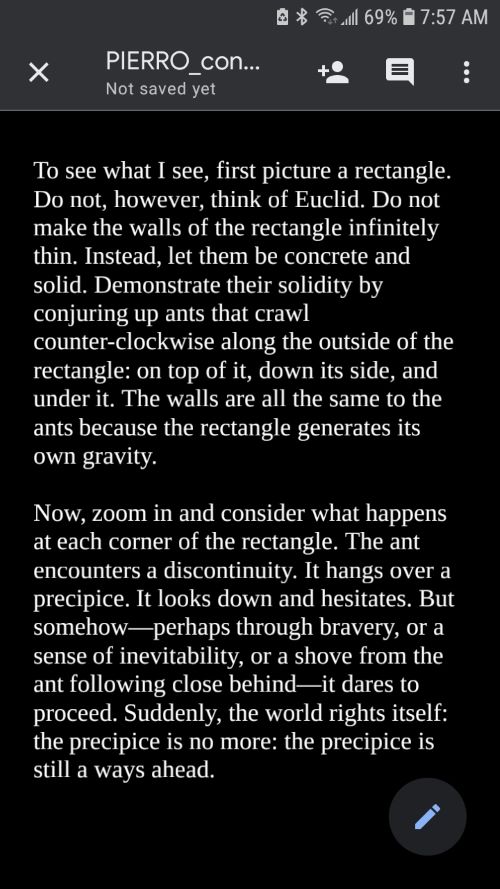

Illustrations by Ravi Zupa.

From: Cat Pierro <cat.pierro@gmail.com>

Date: October 26, 2020 at 8:05:21 AM EST

To: Hypocrite Reader <hypocriterdr@gmail.com>

Subject: “Prophecies” Pitch

Dear Hypocrite,

Many people believe that poetry is otherworldly & that letting it in requires some adjustment. But have you ever considered the fact that it’s almost impossible to imagine this world, mundane though it is, without poetry? Try it: I guarantee you’ll think of a “world without poetry,” quote-unquote. That’s very different from what someone who had actually never encountered poetry would imagine—a “world,” plain and simple. I propose to fully think through a truly otherworldly world, one without any poetry, and to write what would be that world’s very first poem.

Please let me know if this is of interest.

Cat

From: Cat Pierro <cat.pierro@gmail.com>

Date: October 26, 2020 at 7:12:12 PM EST

To: Hypocrite Reader

Subject: Re: “Prophecies” Pitch

Dear Hypocrite,

Just in case you don’t like that idea, I have another one. It comes from a longstanding artistic ambition of mine to paint my surroundings “as I really see them.” This means, for one, that the image would be framed by wisps of my hair, since I have long hair and it usually invades my vision at the edges—as does, depending on in what direction my eyes are pointing, a ghostly view of my nose. Of course, the incorporation of my own body parts would not be the only innovation. Whenever I, or anyone, rest(s) our eyes anywhere, all other points besides that central point appear fuzzier than the central point appears, according to some pattern (a pattern that does not exactly correspond to the points’ distance or proximity from/to the central point; in order to, ahem, “see my point,” try staring at one word in this email and noting which of the others you can decipher). Points at different depths may even appear twice (keep staring at the word, but meanwhile lift a finger and let it hover in front of your face). Not only that, but there are “blind spots,” or so we’re told, though we can’t really see them. A painting “as I see it” would, like seeing, show one spot in focus and keep the rest “peripheral.”

Now, the person looking at the resulting painting would have an experience very unlike seeing. Her eyes could freely roam around the painting, observing the experience of seeing with gentle disinterest. She could choose to gaze directly at one of the fuzzy parts, apprehending as clear as day an experience that normally eludes us. Or she could look at the focused part. If she looks at the focused part, she would find herself in a uniquely mysterious situation—for even if the periphery had been objectively in focus, as in other paintings, it would appear subjectively out of focus to her, since she would need to engage her own peripheral vision to view it. In this case, it would be both subjectively and objectively out of focus. (Only experimentation will tell whether this might make it somehow appear in focus after all, like the product of negative numbers, or if this is one of those cases where “two wrongs don’t make a right,” but either way it’s sure to be profoundly strange.) The experience of vision would be occurring twice—once in the painting itself, by design, and once in the viewer, by human nature: it would be a double vision.

I’ve tried to make an image of this kind, but I stink at painting. My only real talent is writing poems. Luckily, the concept is easily transferable: just as a viewer “sees” a painting, a reader has a certain way of “seeing” a poem; that is, of reading it in the mode of reading poetry. Call it “apprehending,” since there isn’t any word for it. My idea is to present the content of the poem “as I apprehend it,” so that the reader can apprehend the apprehension.

Cat

From: Cat Pierro <cat.pierro@gmail.com>

Date: October 26, 2020 at 10:32:01 PM EST

To: Hypocrite Reader

Subject: Re: “Prophecies” Pitch

Dear Hypocrite,

I forgot to ask: if accepted, what approximate word count would I be aiming for?

Cat

From: Cat Pierro <cat.pierro@gmail.com>

Date: October 29, 2020 at 6:42:41 AM EST

To: Hypocrite Reader

Subject: Re: “Prophecies” Pitch

Dear Hypocrite,

One more poem idea (why not give you a few to choose from)! I’ve been meditating on the purposes of poetry of late. It’s a commonplace that poetry should change the reader—this has been said in myriad ways; to take one example, Kafka suggests that it must be “the axe for the frozen sea within us.” And if it changes the reader, we can agree that it induces her to act. Just as all understanding can be reduced to sense-impressions from past experience, all internal change can be reduced to future external activity, even if that activity happens after a considerable delay.

So far, I think, nothing I have said is controversial. But it has been examined very little. Are we poets trying to change the reader maximally, that is, to bring about a condition whereby her future activity would deviate as much as possible from the activity that would otherwise have taken place had she never read the poem? Perhaps we are. In that case, in order to evaluate our success, we must find some way of measuring activity as a quantity, and we must retain access to the counterfactual future in which the poem has not been read in order to “subtract” the two.

Then again, we may wish to provoke the reader not just to any action but to a particular action, or to an action of a particular kind. This possibility bifurcates into others. Here, too, we might seek a maximum quantity, but now with a direction (e.g., perhaps we want to induce action that is as virtuous as possible, or as devious). Or we might intend a specific and limited behavior (perhaps we want the reader, some specified number of milliseconds after reading the poem, to stand and do a pirouette with a particular radius, axis, and so on).

Just as the ends have not yet been examined with any theoretical precision, the means have also not been examined. One mechanism some poems use in order to multiply their effect is to draw attention to themselves, so that readers read the poem and think, “I’ve got to remember this one” or “I should reread it.” The reader builds a nest for the poem in her mind; she repeats the poem to herself over and over, letting it stick. This orientation toward stickiness explains the obnoxious prevalence of rhymes in poetry, though similar devices exist at all levels of depth beneath the surface—past the poem’s sound structure into its network of semantic echoes and “all the way down.” The poem, like a virus, has enlisted the reader as an accomplice in its own reproduction. It is as if, without refashioning its message, the poem has simply delivered it through a megaphone; it has bent the fabric of space-time and drawn all lines of attention in toward itself at the center. Needless to say, the locale toward which it has diverted our concentration may be completely vacuous; a message repeated a hundred thousand times may nonetheless have no impact. Conversely, some poems draw no attention to themselves whatsoever: the reader looks up, having forgotten the poem entirely—having forgotten, even, that she has read any poem at all. Nor does it occur to her to wonder what happened to those precious minutes of her time on earth while she was reading it. Such a poem may penetrate the reader’s defenses in spite of its slipperiness, though the mechanism of its operation is more mysterious. Evading the corrupting influences of conscious awareness may afford it some advantage. We can suppose that, instead of axing the frozen sea, it glides right through it like a ghost.

Having laid out the groundwork for analysis, I am now in a better position to propose both end and means for the poem I’d like to write. As to the end, I’d like to shorten the time before which the reader next calls her parents, if they are living; and I’d like to do this by means of a poem that, drawing somewhere between minimal and moderate attention to itself, increases the reader’s feelings of filial guilt.

Cat

From: Cat Pierro <cat.pierro@gmail.com>

Date: November 1, 2020 at 2:22:52 PM EST

To: Hypocrite Reader

Subject: Re: “Prophecies” Pitch

Dear Hypocrite,

I hope you don’t mind my tacking on a little addendum. Tl;dr—after an insightful encounter with a worthy consultant, I worry that I may have given you the impression that my poetry risks neglecting concrete sense-impressions in the interest of chasing down formal abstractions; if so, I must assure you that this will not be the case, and I can prove it.

My admittedly neurotic worry stems from a recent incident. The above-mentioned consultant, incidentally my roommate and sister, entered the shared zone in our apartment where I happened to be working (some noisy construction outside my bedroom window induced me to spend time there) and ultimately crossed behind me (I have no idea how long she was standing in the entryway before that, since the hair blocking my vision prevented me from detecting her presence until her foot knocked against my chair leg). I then voiced a request (not unreasonable, I think) that she refrain from reading what was open on my laptop—namely, this very email thread, which I was perusing for some reason that escapes my memory. She retorted, inexplicably, “Why would I want to read that?” Based on the inflection of her voice, she intended her question not curiously but rhetorically: that is, she would not want to read that.

I do not know why she chose to say something so vituperative. If I had to guess, I would venture that she spotted the words “filial guilt” on my screen and took them as a personal attack. It is, in any case, profoundly unlikely that she had inspected enough of the document to make an informed report of her preferences. The point is, however, that after I returned to my own zone of the apartment and pondered the matter, I was persuaded to communicate to her by email that I would appreciate any expanded feedback she could offer, and I attached my three pitches to the email in case her brush past me had not yet afforded her enough time to deliver a sound judgment.

When in the course of human events, it becomes necessary for one writer to relinquish the absolute control she holds over her writing, and to show what was intended for a faceless general audience to a mortal and finite individual, some ambivalence, I think, is requisite. Within seconds of hitting “send,” words began to rearrange themselves on the page; promises rang hollow; phrases that formerly carried specific meanings started to look like empty gestures toward lofty realms. Although she has not responded, I feel compelled to address the critique I am certain she would make: that my pitches suggest poems that are “abstract” and “philosophical,” whereas poetry ought to be “vivid” and “meaty.”

I am writing to let you know that my poem will be both at once. I have every intention of giving my readers something to “sink their teeth into”—some morsel of matter that gives, but never quite gives way. I’m sure you’ll agree that it doesn’t matter what the morsel actually consists in, as long as it’s there to hold the idea. It’s only natural that I didn’t mention which concrete sense-impression my poem will feature, since ultimately it makes no difference, but it’s just as natural that you, the editors, might doubt that I would include any such sense-impression at all! I’m writing to beg you to banish that thought from your minds.

Just in case you won’t take my word for it—and of course you won’t; why would you?—I have attached an example of a concrete image around which my poem could be centered (see: PIERRO_concrete_image.docx). It’s one I dreamed up recently (I dream up such images quite frequently, at a rate of about two a day). The image, though fully fleshed out in the attachment, is underdetermined in the realm of formal abstraction; I can certainly make use of it for any of my proposed poem forms (the alien world poem, the twice-processed poem, or the phone-call-generating poem—still waiting to hear which you’d prefer). And if for some reason this specific material morsel doesn’t please you, I can come up with another. I don’t mean to brag, but coming up with such things is extremely easy for me. If I wrote you an email for every poem-adequate concrete image that crossed my mind, you’d get sick of me very quickly. You can probably now guess the reason for my former omission, but I’ll tell you anyway: wanting to highlight my virtuosity, I foolishly took your confidence in my basic talent for granted.

Cat

From: Cat Pierro <cat.pierro@gmail.com>

Date: November 7, 2020 at 11:08:31 AM EST

To: Hypocrite Reader

Subject: Re: “Prophecies” Pitch

Dear Hypocrite,

I’m writing to follow up on my pitches. Have you had a chance to consider them? Thank you for your time.

Cat

From: Cat Pierro <cat.pierro@gmail.com>

Date: November 9, 2020 at 7:06 AM EST

To: Hypocrite Reader

Subject: Re: “Prophecies” Pitch

Dear Hypocrite,

Scrap all my previous emails. I now have in mind an entirely new genre of poem. The premise (unarguable) is that meanings evolve in time and space (and possibly along other dimensions) such that a sentence uttered at 19° N, 72° W in 1492 means something different when uttered again at 72° N, 19° W in 2941. In light of this, the piece will be superficially identical to some stodgy old poem, such as William Shakespeare’s Sonnet 18—one that’s currently innocuous and utterly devoid of any hint of incitement to action—and it will wait innocently, buried in the archives, like a monkey at a typewriter that keeps typing the same thing over and over, until the moment is right, at which time it will be programmed to “activate,” circumstances having so altered that the poem will have come to take on a new meaning. The only thing is, I don’t know if it should be set to “activate” once it has come to mean a particular thing, and if so what, or once it has attained the maximum possible quantity of meaning that it will attain in its lifetime, and if so how it will know (I imagine dynamic programming could be of use here). I must also confess that I’m not sure what the “activation” will specifically look like or whether it will be dangerous. But I do know with certainty that the poem must not bear my name or any other immediate indication of its originality; it must appear on the page exactly as if Hypocrite had simply re-published “Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day?” (or similar). Now I know it may make the editors uncomfortable to seem to take the magazine in such a stodgy direction, but I assure you that very few readers will even notice the poem on the homepage for the time being on account of the sonnet’s present-day toothlessness.

Cat

From: Cat Pierro <cat.pierro@gmail.com>

Date: November 9, 2020 at 5:56:20 PM EST

To: Hypocrite Reader

Subject: Re: “Prophecies” Pitch

Dear Hypocrite,

Never mind my last email. I forgot to anticipate the death of the English language.

Cat

From: Cat Pierro <cat.pierro@gmail.com>

Date: November 11, 2020 at 10:18:43 PM EST

To: Hypocrite Reader

Subject: Re: “Prophecies” Pitch

Dear Hypocrite,

My first pitch was accepted elsewhere, so I am withdrawing it. My last pitch suffers from a fundamental conceptual flaw, as I already mentioned; I feel deeply embarrassed for having hit “send” on that one before I’d had the chance to think it over.

My second and third pitches still stand, awaiting their respective fates.

Cat