Hannah Taber

Stay Hungry

ISSUE 8 | HUNGER | SEP 2011

Illustrations by Tom Tian

In the most desperate situations, one is sometimes forced to undertake a hunger strike, of which, generally speaking, there are two types1: political hunger strikes, which have a robust and compelling history in places like India, Cuba, and Northern Ireland; and romantic or interpersonal hunger strikes, on which there is relatively little literature and which are more likely to occur in the context of graduate school or parental correspondence. Typically, a strike is initiated as a method of nonviolent resistance and/or to apply pressure on a perpetrator of injustice. Whatever its specific purpose, a hunger strike must be noticed, perhaps even make a statement, creating a spectacle on which the hunger striker subsists as a normal person would on food. Two examples for the purposes of illustration:

October 10, 2010. Celtic League Secretary Michael Chappell initiates an 11-day hunger strike to protest the British government’s treatment of the territorial integrity of Cornwall. In the end, he claimed to have lost a stone in weight.September 5, 2011. I decide to stop speaking, ad infinitum, to a friend on whom I have had a crush for one year to protest his treatment of my easily bruised feelings. Results pending.

Of course, Mr. Chappell–now buckling his belt an impressive eight holes tighter–enjoyed a key advantage that the interpersonal or romantic hunger striker does not: a pervasive media. Not even the news-starved daily press of the most insignificant town would publicize a local resident’s valiant effort to repair a damaged relationship through silence and feigned indifference. Here, I should interject to underscore a critical distinction between interpersonal hunger strikes and “the silent treatment” or similarly bromidic behaviors. There are no well-defined criteria or aims to regulate the latter, and they inevitably form part of the uninteresting adhocracy which seems to describe much of human interaction. It is one thing to become upset with someone and indulge an impulse to stop speaking to him until one “feels like it.” A hunger strike is an entirely different matter, as connoisseurs of passive aggressive behaviors will zealously point out. It often follows days of careful reflection, employed as a last resort to correct the egregious and seemingly incorrigible negligence of a wayward friend or romantic interest. The formidability of its terms–deliberate and emotionally demanding–ensures that it is not taken up lightly or spontaneously. If an interpersonal hunger strike is ultimately a campaign to inspire awareness, such awareness is best understood not as a beneficial externality but, rather, as the offender’s resultant acknowledgement of the striker’s worth, signaled by a nontrivial improvement in the former’s basic attentiveness or by other previously uncharacteristic displays of empathy.

Most seasoned practitioners acknowledge that hunger strikes in the context of personal relationships–as compared to those undertaken for the sake of a widely-shared cause or ideal–are relatively mild but still unpleasant, entailing a strict regimen of complete social and emotional deprivation and obligating the instigator to abstain from initiating any communication with the offending entity, though it is sometimes permitted to respond to such advances initiated by the other party in a way deemed prudent by the striker. The intrepid pioneers of the interpersonal hunger strike were primarily young children who refused to speak to their parents for up to one hour (maybe several), after which point they usually acquiesced to the offer of some small enticement–a piece of chocolate calculatingly passed across the negotiation table–or, if the stakes were especially high, the threat of indefinite grounding, which universally carried the strike to its endgame. Like middle distance runners in training, many of these children would, as they grew older, heighten their efforts to full attrition warfare, forcing inattentive friends and loved ones to seek redemption by maintaining overwhelmingly superior force of will and strength of conviction–powerful nonverbal tactics which, when employed against a weak character with the proper dose of affectation and self-righteousness, are more than enough to achieve unconditional surrender.

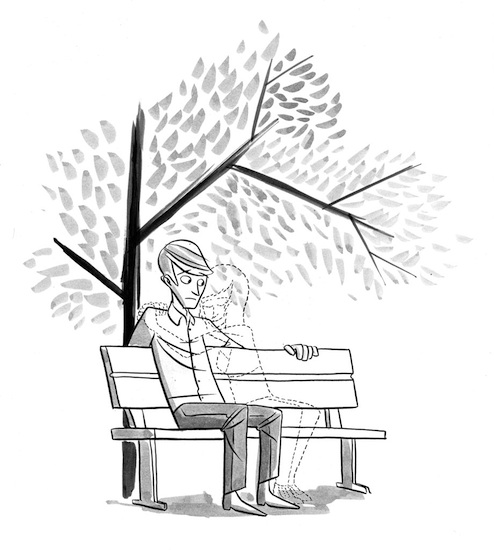

Much study has been devoted to the biological aspects of hunger–the body’s response after prolonged periods without food, the sorts of physical sensations and medical conditions associated with hunger, and the point at which one reaches the precipice of starvation. Metaphorical hunger proves to be a more elusive phenomenon, and its timeline is far less predictable. Romantic hunger strikers, unable to pinpoint exactly when their diet of the heart will begin to produce gratifying results, must accept a high degree of uncertainty and the likely possibility of a prolonged struggle. These circumstances are especially difficult to weather if one’s academic or professional obligations are not enough to fill the daylight hours and leave the striker in the pit of exhaustion at day’s end. A schedule which permits even a minimal amount of leisure and personal meditation can be damning to someone doing her best to vanquish the temptation to make a forbidden phone call. At the same time, the striker is faced with yet another challenge: to achieve a delicate balance between avoiding the offending party and making an effort to occasionally be in his presence–albeit at a distance–in order to make one’s silence truly felt. Only the most adroit strikers are able to remain sufficiently conspicuous while simultaneously minimizing the risk of actual interaction. Indeed, such perils should be enough to dissuade the faint of heart from ever attempting such an exercise.

The empirical track record of the romantic hunger strike is dubious, given the unfortunate dearth of carefully collected data. My lack of endurance is regrettable, but I imagine that some people can carry on for days or even weeks. Here, I must highlight a particularly treacherous aspect of the romantic hunger strike: If the individual against whom the strike is initiated is truly as aloof as one would presumably have to be to merit such an action, the strike carries a high risk of going unnoticed. And even novices must realize almost immediately that the criterion of visibility is crucial for the ultimate objective of a romantic hunger strike: to force the person to hunger for the striker as the striker, ever tormented, hungers for him, appealing to his hardened conscience through silent but increasingly evident suffering–suffering for which the wrongdoer should be made, stealthily and indirectly, to feel as guilty as possible.

Ensuring that this last aim is achieved requires a great deal of patience and, above all, a steel resolve to cross the offending party out of one’s life until he repents, verbally or through a change in behavior, for the emotional turmoil he has created through his unequivocal inconsiderateness. It may be a week or more before the striker’s absence is felt and the offender musters the thoughtfulness to make sustained eye contact or send a noncommittal text message. Such is the nature of my current endeavor, a particularly taxing hunger strike that after eight days has produced from its target one very brief multiple-recipient email about the utterly prosaic matter of whether the message’s recipients will be attending a recently-scheduled boat cruise for students in my graduate program (a message to which I will obviously not reply, given my dual hatred of boat cruises and cop-outs). In short, the romantic hunger strike almost always involves a large effort for a small and uncertain prize, though one could argue that it is impossible to put a price on a lean conscience. More often than not, the striker begins to resemble an anteater rooting blindly through a pile of sand–an anteater whose friends would agree would be better off searching elsewhere for sustenance.

The question is likely to arise, then, of why one would ever initiate a hunger strike in the first place to preserve a relationship that is evidently unhealthy for at least one of its participants. If such questions had easy answers, people like Joni Mitchell and other prominent figures of the “lover’s lament” genre would not have profitable careers. Indeed, we owe a great cultural debt to the ambivalence and irrational persistence of the victims of unreciprocated infatuation, who seem to become bitter, prolific authors or singer/songwriters (admittedly of varying quality) at a disproportionate rate. The incredible level of restraint required by hunger strikes undertaken to salvage the most unfulfilling relationships is a large but oddly worthwhile expense incurred in pursuit of romantic solace. After the long silence that comes with being alone in one’s principles, the ultimate reward of a hunger strike will likely depend on the striker’s goals and expectations in the first place–a complete transformation of the offender, a somewhat heightened awareness of the striker’s existence, or merely the satisfaction of having strategically deprived a self-centered individual of attention. My own hunger strikes–of which there have been enough to force me to doubt my social aptitude–have encompassed a sometimes-confusing combination of these objectives, and they are often abandoned after a few days, before I can claim to have shed any emotional weight. The temptation to readopt my habitual congeniality, combined with an utter lack of self-control when it comes to inappropriate crushes, is enough to cut short even my most purifying of fasts.

I am convinced, however, that my present hunger strike will mark a decisive turning point in my troubled relationship with its target–a friend and love interest whom I got to know, oddly enough, by offering him a piece of chocolate.

1 As noted in Franz Kafka’s “A Hunger Artist,” hunger strikes for entertainment are no longer viable and therefore do not merit their own category.