Leah Gallant

The Blackest Black Thing

ISSUE 77 | BLACK AND BLUE | JUL 2017

1.

In 2014, British lab Surrey NanoSystems announced that it had developed the blackest coating in the world. Vantablack, which stands for Vertically Aligned NanoTube Array Black, is composed of lots of very thin carbon tubes, which are so disproportionately tall that they trap 99.965% of light. The only thing blacker than this coating is a black hole, from which no light escapes.

This has the effect of rendering stuff virtually invisible; because there are no shadows or highlights, it is impossible to gauge the contours of an object coated in Vantablack. This flatness has a number of applications: for disguising military aircraft, for satellites and other specialized space instruments, and, of course, for luxury objects, such as limited-edition deodorant. In one image from the lab, a crinkled piece of aluminum foil registers not as flat or convex, but as a hole in the visual field, a negation of sight itself. The gaze is a question which this black refuses to hear.

In another video, a hand in an orange plastic glove sweeps a round of Vantablack at the end of an aluminum stick back and forward against a Vantablack ground. It’s like a lollipop, but a black hole. The camera angle sweeps above, to the side, then back above. It is impossible to gauge the sphere’s distance from the ground; they merge in a way so obvious it is impossible to imagine they were ever two separate black-coated objects.

2.

Vantablack is built of a “forest” of nanotubes, which are tiny carbon tubes, each one 1/10,000th the width of a human hair, packed densely together. Surrey Nanosystems defaults exclusively to forest and field analogies to explain where this darkness comes from. Says director Steve Northam: “Imagine you have a field of wheat, and instead of the wheat being 3 or 4 feet high, it’s about 1000 feet tall (…) It will stay upright and not blow away in the wind, but if you then try and land a plane on it, you’ll make a dent.” Or, according to the website FAQ: “Try to visualize walking through a forest in which the trees are around 3km tall instead of the usual 10 to 20 meters. It’s easy to imagine just how little light, if any, would reach you.”

Here is a stock photo of a forest from Surrey NanoSystems’ website. I’d guess it’s some kind of evergreen, which means something that is green forever but not necessarily the greenest green at a particular point in time. Its greenness is durational. The camera is angled up diagonally, as though you were tipping your head back to look up at something heard or perceived overhead but at the moment you would have tipped your head all the way back so that your face was parallel to the dirt and the sun something happened and you stopped.

This photo of a forest is meant to illustrate the idea of light blocked out by a canopy of densely packed and super-tall trees. You are supposed to look at it and pair it with what you have just read, which is that if the nanotubes were trees they would be so tall that no light reaches the surface, the substrate, the forest floor where you’re walking. But the switchback between the observer and the observed is unsettling. You are asked to understand the darkness outside of this forest by imagining yourself inside it.

3.

Vantablack is, according to the FAQ, “the world’s blackest paint.” Not the universe, but the world, and not the blackest black but the blackest paint. This is the description of Vantablack S-VIS, the sprayable cousin of Vantablack. (It was incorrectly reported by multiple online sources as available for use in the form of spray paint; in reality, although it is sprayed on, like the original Vantablack it requires a stabilizing process that make it impractical for DIY application).

It is referred to it as the darkest black, rather than the blackest black, as though a noun wielded on itself as superlative would puncture the soft belly of language. The big reveal is that black as platonic ideal does not exist. There is no absolute gold-standard black against which every other is defined. It exists in language as a placeholder. If the phrase ‘blackest black’ is allowed to carry a meaning, that the color in question is not quite darker but more thoroughly or intensely performs its blackness than regular old black, then black is generally grey.

To try to hold a thing as more-itself I imagine it luminous and quick, chattering at the edges with its impatience to become-more-than-what-it-is. It is hyper- its own self. I picture it like the relationship between speed and lightspeed. The static stuff (stars) visible through the portholes of the Starship Enterprise as it lurches into lightspeed are rendered smears. And this is how I picture even those things whose identifying features have nothing to do with speed or light or space, for example, the tabliest table not only surpasses its function or its form, it is absolutely an elevated plane on four legs which sucks your legs under it and writing forearms on top of it. It is also surrounded by a sort of force field or mandorla, it is so exactly what it would overtake that it oscillates and generates light. Vantablack is the Splenda of blacks, a god among men. It takes the form of color but it hails from some other realm, where color refutes the gaze.

4.

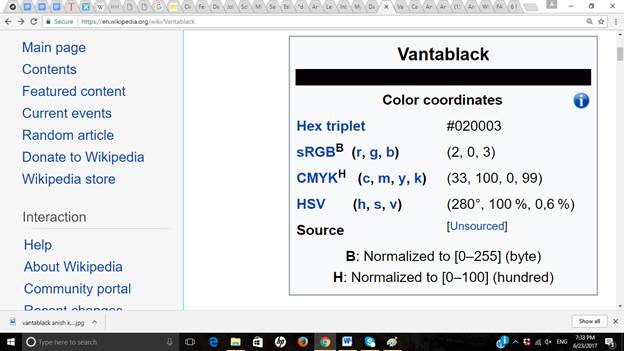

Is color the only thing whose classification forces an encyclopedia to admit its own inadequacy?

There is no standardized color rating system in widespread use. “A [color i.d.] box with all of the different possible coordinate ranges would be too large and confusing,” states Wikipedia.Wikipedia has its own system of quantifying color based on sRGB (Red, Green, and Blue Light on a scale from 0 – 255), CMYK (Cyan, Magenta, Yellow, and Key (Key means black) on a scale from 0 – 100), and HSV (Hue, Saturation, Value). The last, and most bewitching measurement, is called Hex triplet. (“CMYK is generally something of a disaster,” the Wiki says later, still trying to sound detached).

Hue ranges from 0 to 360 degrees, and tells you where something is on a color wheel. At 280 degrees, Vantablack is just above Violet, which is 270 degrees. edging over into Magenta, the next nameable color, at 300. This doesn’t seem right, because the darkest unblack color seems like it should be a blue so deep it edges into purple. But this is what I mean about the chattering edges, the leapfrogging into another realm of sight. A super dark thing, the blackest black material, is more like a supersaturated maroon, so many layers of maroon it transforms into a black.

5.

If Vantablack is a point of convergence for many things we know to be true of other materials—the miasmic nature of color, but also how the development and deployment of color is grounded in its object-ness, its production as a physical thing—as well as the primary audiences for innovation, the military and space exploration, then it is also a truism that the upper echelons of the art world have little to do with truth, or beauty, or the avant garde, and everything to do with cash.

In 2016, British artist Anish Kapoor secured exclusive rights to Vantablack’s use in art. Despite the various barriers to using it – that it must still be produced in a lab, for example – this enraged various artists of the internet, including fellow British artist Stuart Semple, who holds that all materials should be usable by anyone.

The art historical precedent for Kapoor’s claim is International Klein Blue, the color developed and registered by French artist Yves Klein in conjunction with a Parisian chemist in 1958. Klein used this color, a super-saturated ultramarine which I’ll anachronistically compare with Facebook Blue, as art in several different contexts: as pigment available for retail, as medium to make paintings with, both by hand and by having naked women roll around in it. The key difference is that Klein’s work was premised on color-as-commodity, artist-as-brand. Although there were objects to look at, the crux was conceptual; the color itself was the art. Having declared a color art was the art.

Stuart Semple manufactured a counter-product in protest, the pinkest pink in the world, available for purchase on his personal website on the sole condition that the buyer promise to keep the pigment out of Kapoor’s hands. (The glitteriest glitter appeared soon after.) Soon after, Kapoor had posted a photo on his Instagram of his middle finger dunked in pink and the caption ‘Up yours.’ This is why you should never leave children unattended.

6.

How can criticism can be written in the age of the quasi-invisible art object?

My eyes would be incapable of registering what I was looking at.

I have access neither to Kapoor’s artwork – it does not yet exist -- nor to the material that will constitute it. Even if I did, I would not be allowed to touch it. In its symbolic and real fragility, Vantablack is art world-ready. The blackest black material is just like other things I cannot touch, like the Mona Lisa or a butterfly wing or the president’s jugular.

The critic no longer has stuff to see, and what stuff there is to see no longer has the qualities of the visible.

But it does not matter, it’s not the idea that drives the art anymore but the headlines that precede it and the backlit photographs that follow in its wake. I already ‘get’ Kapoor’s future superblack work without having seen it. The art object in the age of the internet has been surpassed by its document.

7.

Euro Business Park is visible from outer space.

So I have deployed myself to the best vantage point for a critic to be in the age of Vantablack. I have not left my couch.

Though denied access “IRL” to the subject of analysis, through Google Maps I maintain virtual access to the place of its manufacture. I decided to “go for a walk” in a certain industrial park in Newhaven, England, at the mouth of the River Ouse.

I touched down at Unit 24, Euro Business Park, New Rd, Newhaven BN9 0DQ, UK, the birthplace of the blackest black the world has ever seen.

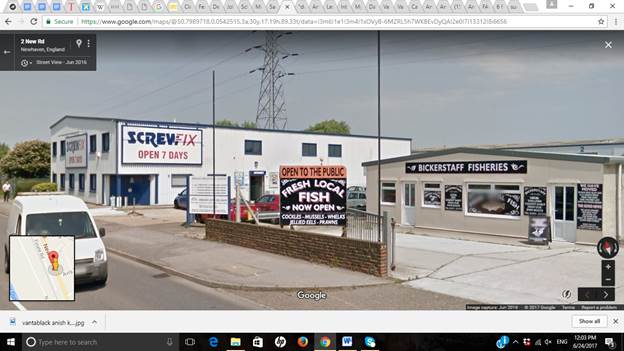

There was a low one-story building on my left with the letters CEF in red squares. All the buildings were made of ruffled metal siding, like the texture of a clam shell, and the cars were driving on the wrong side of the road.

Rare pedestrians discovered within blocks of Surrey NanoSystems.

I imagined the roving camera that preceded me, slurping up image at dawn. I imagined it camo-print, like a tank, but we know already the twin language around the operation of a camera and operation of a gun, we know they both shoot.

According to my map, the hangar-like building was the right place, but I had landed on the wrong side of it. I went looking for a sign or main entrance.

Across the street, next to ScrewFix Open 7 Days, was a fish shop swimming in its signage. OPEN TO THE PUBLIC, it said, FRESH LOCAL FISH NOW OPEN. COCKLES MUSSELS WHELKS JELLIED EELS PRAWNS. Perhaps the very hands that had manufactured the blackest black in the world had purchased the daily catch at Bickerstaff Fisheries.

I walked down New Road to where it intersects with Avis Way. In the distance, down Avis, past Avis Industrial Building, a town was visible on the hill. Maybe it is where the scientists live.

There was a truck at the intersection that I kept trying to zoom in on, I wanted to see the drivers’ faces, but when I got closer the truck had disappeared. I kept toggling back and forth. It reminded me of the back and forth motion of the Vantablack Sphere on the Vantablack ground: it was one minute visible and gone the next. The dashboard was full of stuff, there was some butter yellow mass in the middle, and the faces of the drivers had been blurred.

I turned around and walked in the opposite direction, towards the intersection with Estate Road.

I zoomed in and squinted into my brilliant screen. It was the sign. I had arrived.