Michael Kinnucan

Some Labor Disputes in the State Violence Industry

ISSUE 72 | PRACTICE | FEB 2017

Racial Insurrection and Republican Politics

There’s an intimate yet somewhat obscure connection between a certain strain of right-populism and the idealization of workers in the state violence industry—cops, soldiers, prison guards, border guards. It’s not only that right-populism offers security to ordinary citizens, and that violence workers are the means to that security; there’s more to it than that. The imaginative focus is not so much on the peace that will be achieved once the cops crack some heads as on the cops themselves, doing the cracking; in this mental universe, the cop is the ideal citizen, his cracking heads the civic act par excellence.

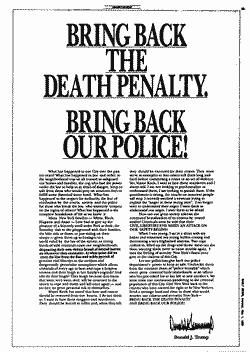

It’s no accident that the police unions were among the first to endorse Donald Trump, or that the border patrol union broke decades of tradition to endorse him. They heard something in his depictions of the “carnage” and chaos of modern American life and his demand that actions, not words, be brought to bear on this chaos, a reflection of their labor conditions—the world as it appears to cops; they thrilled to it. And not for the first time. The Trump-cop connection goes much farther back; the racist police system has everything to do with his political career and the strain of paranoid politics it represents. The man who described American cities as “carnage” in his inauguration address last week is, after all, the same real estate developer from Queens who, way back in 1989, when Ed Koch was mayor of New York City, spent $85,000 placing a full-page ad in every paper in the city demanding the execution of the Central Park Five.

Bring back our police: the cop is not only the ideal citizen but, Christ-like, the eternally betrayed one. Who betrays him? Liberals, talkers, those who would rather understand and psychoanalyze than act, those who in their blessed innocence can afford to think that a city doesn’t need cops. It is this note that has caused not only police but those other fists of the state, the border patrol, to thrill to Trump’s side: they feel betrayed, hard done by. As the National Border Patrol Council, the ICE union, wrote in endorsing their first presidential candidate ever: “We represent 16,500 agents who selflessly serve this country in an environment where our own political leaders try to keep us from doing our jobs.” (In the hours after Trump's Muslim ban was stayed by a federal judge, disturbing reports emerged that Customs and Border Patrol agents were ignoring the court order and deporting people anyway.)

This sense of grievance and betrayal—not entirely unjustified, as I shall try to show below—seems to be a natural product of violence workers’ conditions of labor; it’s as fresh now as it was in 1989, and it has left a lasting impact on the politics of New York and many other cities. Not many years after Trump placed that ad, Rudy Giuliani rode a thousands-strong police riot to the mayoralty on much the same issue and made New York the most police-ridden city in the nation.

Most of my friends on the left, who thought about nothing but police politics two years ago, aren’t thinking too much about it now; it’s hard to focus on normal violence when so much abnormal violence seems threatened. But I think forgetting about the police, even temporarily, would be a mistake. It’s not entirely an accident, after all, that the Trump presidency comes in the wake of Black Lives Matter, the largest and most visible contestation of police violence in decades. Despite coastal liberals’ tendency to project racism into a geographic and cultural elsewhere, it’s not an accident that Donald Trump is from New York, and understanding the intimately linked worlds of policing and real estate in the great northern American cities is important to understanding what he means. Normal, localized state violence, and the contradictions it entails, and the rhetorics and mentalities and political imaginaries it makes possible, don't stand in isolation from national politics; they're omnipresent, and they fester.

Corrections

On November 18, 2013, in the final weeks of the Michael Bloomberg administration, the New York City court system ground to a halt. The corrections officers responsible for transporting prisoners from Rikers Island to court appearances elsewhere in the city announced that the buses had broken down—all of them, all at once. It wasn’t hard for court insiders to see what was happening: a Rikers inmate named Dapree Peterson was scheduled to testify that day against two corrections officers who had been caught on video beating him and had then lied about it in incident reports. The corrections officers, led by their extraordinarily powerful union boss, Norm Seabrook of the Corrections Officers Benevolent Association (who stepped down last year after being indicted for corruption), had decided to shut that trial, together with the rest of the city’s legal system, down for the day.

Peterson testified the next day; the prison guards had made their point. His assailants, despite strong video evidence of their guilt, were later acquitted.

New York corrections officers are barred from striking by the state’s Taylor Law, but wildcat job actions are nevertheless common during contract negotiations, and there is significant precedent for job actions defending their right to beat inmates: in 1990, a corrections officers strike during contract negotiations over repealing restrictive use-of-force guidelines was followed by a prison riot when news broke that the restrictions had in fact been eliminated.

The enormous strength of COBA, its willingness to engage in extreme and illegal tactics, and its focus on protecting its members from any accountability for brutality against inmates goes a long way towards explaining why Rikers, like other New York correctional facilities, remains extraordinarily violent and dangerous despite decades of court injunctions demanding reform. The right to beat prisoners without facing consequences is an important element of corrections officers’ working conditions, and they defend it assiduously.

Police

The New York City police force has proven no less assiduous in rejecting limits on its officers’ authority to use force. Most recently, in the wake of massive protests against the strangling of Eric Garner by Daniel Pantaleo and the latter’s non-indictment, Patrolmen’s Benevolent Association officials, including union leader Pat Lynch, were intensely critical of what they saw as Mayor Bill de Blasio’s sympathy for the protesters. After an unhinged gunman killed two police officers in December 2014, police blamed the mayor personally—what did he expect, objecting to the strangling of citizens? In response, they first turned away from the mayor at the fallen officers’ funeral, then engaged in a weeks-long unofficial work stoppage, with arrest rates declining 66%. But direct and indirect police action against civilian oversight of police behavior has a long history in New York. Tensions between minority communities and the police go back decades (to choose an incident at random from a very long list, an officer shot a ten-year-old boy in 1973 and was acquitted at trial), and with each incident calls for greater police accountability are met with massive resistance.

The decades-long battles over the makeup of the Civilian Complaint Review Board are an excellent example; the CCRB’s history dates back to the 1950s, but initially its board consisted exclusively of police officers. When Mayor John Lindsay attempted to institute civilian (non-police) control over the board, the PBA forced a citywide referendum on the issue and blocked the initiative, threatening a crime wave if civilian oversight stood. New calls for reform came in the wake of extraordinary police violence against protesters in the 1988 Tompkins Square riots, but it was only in 1992, after the Crown Heights riots had highlighted intense dissatisfaction among poor African-Americans with how the city was run, that Mayor David Dinkins instituted full civilian control. In response, the PBA staged a massive, 10,000-strong riot at City Hall, with none other than Rudy Giuliani at its head.

It was a career-making moment for the man who would go on to run New York City for a decade, and whose administration would come to be profoundly identified with the police. Giuliani’s Broken Windows policing strategy was notable not so much for its brutality as for its intensity; the mayor did his best to bring “a cop on every corner,” in Bill Clinton’s famous phrase, to the city. Police interactions with working-class racial minorities had always been brutal but never had their contact with the armed state been so frequent, comprehensive, all-encompassing. Giuliani’s police politics changed the texture and lived geography of the city permanently. In a city that never sleeps, the parks are now empty at night.

Actual Power

The cops who rioted with Giuliani at their head needn’t have worried about the CCRB. Though civilian-run and notionally independent of the police department, it lacked any real power. It could not discipline officers, only recommend that the department discipline them—and its recommendations were routinely ignored. There were problems with the investigative process too: the CCRB was underfunded, its investigations blocked by police solidarity and witnesses who stopped cooperating, its investigators overly sympathetic to the cops they were supposed to be disciplining.

To give you an idea: In the wake of Eric Garner’s killing, CCRB head Richard Emery, a De Blasio appointee and a close friend of then-police commissioner Bill Bratton, ordered a review of CCRB chokehold complaints. Chokeholds had been in violation of police policy since the early 1990s, yet the CCRB had received 1100 complaints about them in the years 2009-2014. Of those, only ten had been “substantiated” (deemed by the board to have occurred). Chokeholds had, in other words, been utterly routine, and the civilians subjected to them had had no recourse whatsoever to see their assailants punished. Eventually, unsurprisingly, someone died.

It is difficult to convey to those who aren’t subject to police or corrections violence and who don’t follow the issue as activists just how unlimited the power of cops and prison guards to beat people is. If a cop in the course of his duties assaults you for no reason, he will almost certainly not be investigated; if investigated he won’t be indicted; if indicted he will not be convicted. Nor will he be fired from the department or otherwise disciplined. There is no effective law restricting police violence in New York City. If you’re white and middle-class it probably won’t happen to you, and if it does you can always sue the city; New York has paid out tens of millions of dollars to victims of police misconduct over the years. But this city has plenty of cops who have cost the taxpayer hundreds of thousands of dollars in lawsuits, yet remain on the force. All this goes double and triple for prison guards; no one cares if a felon gets his jaw broken, after all.

What is perhaps most striking about the corrections and police officers’ job actions described above is their wholesale disregard for public opinion. Corrections officers shutting down the judicial system to intimidate a witness, or police turning away from the mayor at their comrades’ funeral, didn’t look to the general public like an appropriate response to real grievances; it looked insane. All the more so given that neither group has the legal right to strike, so these were “wildcat” operations.

Workers in the state violence industry, though, don’t need to worry about public opinion, because they have what workers in virtually every other industry have lost: actual power. The mayor can’t govern, or doesn’t believe he can govern, without them—not even for a single day. The city’s continued existence depends on the sustained application of police and punitive power; hence the workers who apply that power have enormous leverage in negotiating with the city they protect, and always will.

Theoretical

The executive power in general and the police in particular have been a bit of a scandal for political liberalism for as long as political liberalism has been around. The liberal tradition dreams of closing the circuit of representation, making the governors identical to the governed. If such a thing is possible then the enunciation of a law will be sufficient for its enforcement, since each citizen will recognize his own will in its very form.

It will be beautiful to see, if it ever happens—a government of laws made men. In the meantime, someone must enforce the laws, not against the consenting governed but against those who encounter the law as an alien, foreign power, and must do so not in some special liberal way but in the way laws are enforced under every regime: through violence, threatened or actual.

Our government does its best to carve out a distinction between legitimate and illegitimate violence, through procedures perhaps most properly compared to ritual purification: procedures every TV-watching American knows by heart, from Miranda rights to the rites surrounding the electric chair. But at bottom the distinction is never deep enough; pure force always slips through.

Hence the confused sense of shock and revulsion many experience when they witness officers making an arrest of an uncooperative civilian. It doesn’t look like the application of norms; it looks like a kidnapping! And yet what else could it possibly look like? What was I expecting? Kidnappings may in certain situations be socially necessary, yet kidnappings they remain.

Scandal and Hypocrisy

More concretely: We live in a society which wishes to preserve its citizens from exposure to brute force, and yet which desires to preserve a social system which can only be preserved at the cost of brute force. If you want the ghetto without the cops, or the prison without the beatings, you want the end without the means. You want a contradiction.

This contradiction is of course by no means inescapable. One might become a reactionary and affirm prison, ghetto, police and beatings alike as figures of divine justice; one might become a revolutionary and condemn them all. But mainstream opinion in the United States, even its enlightened, liberal variant, has taken neither path; it just keeps on believing such blatant and irreconcilable contradictions as that the War on Drugs is absolutely necessary and yet, also, in addition, Fourth Amendment rights are sacred.

The consequences are obvious: again and again, decade in and decade out, mainstream opinion in the United States discovers that the police did some unspeakable thing—killed a 10-year-old boy, choked an old man to death in broad daylight—and again and again they are scandalized, and measures are taken to prevent such terrible things from happening, and then it happens again.

Of course it doesn’t happen only once every few years, it happens constantly. It happens every night. But it usually doesn’t leave a body or a video tape. Every few years it becomes undeniable, and something must be “done.”

Grievance Procedures in the Violence Industry

In this light, the intense hostility of state violence workers and their union representatives to virtually any incursion on their right to be violent without consequence appear not merely understandable but more or less justified. Imagine working in Rikers Island, or policing drug dealers in Bed-Stuy; imagine working to harm people who loathe you and would harm you if they could, and imagine that a significant element of your safety depends on their knowledge that you have an unchecked power of violence over them. Imagine, leaving safety aside, that your job is to be violent towards them—to carry them off in chains. Now imagine that on top of being required to be willing to beat people up as a condition of employment you’re also faced with the proposition that if you beat them up too hard, or in the wrong way, against the rules in the training manual, you could face firing or prosecution. Of course you’ll say the people writing the rules have no idea what system they’re dealing with or how it works.

And you’ll be right: They don’t want to know. Mainstream liberal politicians don't want to know what goes on in prisons or how the police work. When that knowledge is thrust upon them they take measures to prevent such grotesque scandals from recurring, but fundamentally they are unwilling to bear the political costs of the radical reforms which could change things. They’re in bad faith.

De Blasio and the Wholesale Failure of “Progressive” Police Reform

Bill de Blasio’s administration might have seemed to a superficial observer—it did to me—like an ideal, once-in-a-lifetime opportunity for police reform. De Blasio ran against stop-and-frisk; then Ferguson happened. Then Garner died. A mayor who had positioned himself as progressive on police reform faced the clearest evidence possible of police misconduct in his own city, with mass protest and majority opinion alike demanding that something be done.

Nothing of substance was done. After running against the police, De Blasio immediately moved to reconcile himself with them by appointing Bill Bratton; his expressions of sympathy with the protesters after Garner died never went farther than words. After even those words were met with work stoppage by the police, he became even more cautious.

The Black Lives Matter protests and the police reform movement more broadly have always been deeply ambiguous, oscillating between the reformist demand for better police and the the radical demand for fewer police. Perhaps most protesters only wanted the police to follow the rules; they demanded things like body cameras, better disciplinary practices, racial sensitivity training, independent prosecutors who could get indictments when things went wrong.

What is most striking about this liberal-reformist strain of activism, the one De Blasio seemed to represent, is that it fails even on its own terms. The most basic conceivable demand for getting police to follow the rules in New York City is a CCRB with actual disciplinary power, granting civilians the right to fire bad cops even when their comrades in arms want to protect them. Yet that was never even on the table. More recently, the Right to Know Act—requiring no more than that cops provide their names to citizens they interact with and obtain written permission for searches, requiring in other words no more than that the cops not be protected by a cloak of anonymity and not violate the Constitution—was blocked in the City Council by De Blasio-aligned speaker Melissa Mark-Viverito; in its place she came to a non-binding agreement with the department that they modify their (unenforced and unenforceable) training procedures on this issue.

De Blasio’s legacy on police accountability is pretty much nothing. Perhaps his most lasting move on these issues in his first term was his decision, a couple of years ago, to hire 1,000 new cops.

Where Next?

The dead end of liberal-progressive can be good for us if we learn the right lessons; maybe movements always need to experience the failure of moderation before they turn to more radical measures.

What are the right lessons here? First, that attempts to limit the ability of violence workers to be violent are unlikely to be effective; once you’ve granted someone the right in principle to violently control someone else, it’s hard to limit the scope of that violence. Second, that attempts to restrict the use of violent force by violence workers will be met with intense resistance by those workers, and this resistance will be extremely effective since violence workers occupy a key strategic node in the state. Attempts to work around this problem with tact will result in half-measures; attempts to meet it head-on will run into a wall.

So what should we do now? The key if submerged dispute within police reform is between those who demand better cops and those who demand fewer cops. We should side with the latter. We cannot make policing or prison non-violent—obviously, by definition. If we wish to reduce police and prison violence we must reduce the number of people entering prison and interacting with police.

In the short term, this means steadily extricating the law from our everyday to the extent possible. Legalize drugs, legalize sex work, legalize public drinking, legalize loitering, legalizing being in the park after dark. Take a long hard look at all the occasions on which working-class people interact with the police in their everyday lives and simply get rid of as many as possible. Likewise, shut down jails; close Rikers Island. Immediate bail reform and liberalization including ending cash bail will accomplish this very quickly, massive sentencing reduction will be important in the longer term.

In the longer term, eliminating police and prisons would mean profoundly altering the profoundly unequal society which depends upon them to maintain its unjust order. But we don’t have to wait for the revolution; we can start now. This is a good year for it, too.