Hope R. Henderson

Colorado River

ISSUE 68 | ECSTASY OR ATTENTION | SEP 2016

Those early months are a haze of sex and heady conversation, followed by giving each other more sweat, more pleasure, by way of breakfast offerings that would please Queen Calafia herself: large purple beans with black speckles, cooked just to tenderness and served with scorched zucchini and padrón peppers. Fresh pasta topped with broiled asparagus, black pepper, and an over-easy egg. Bourbon french toast piled high with mascarpone and blackberries. And always, always coffee: sometimes French press by the quart, sweet with cardamom, milk, and honey; at other times, small, white cups of inky espresso.

She has a love for the open road, and after years on either coast, I’ve grown curious about the expanse in between. So, we fly to Ohio to pick up a Jeep and trailer she had left there with a friend, and start the ten-day trip back to California. We camp in the lush green of the Ozarks, and follow Route 66 through St. Louis and Oklahoma City. We camp in the scrubby desert of New Mexico where coyotes howl all night. After that is the Grand Canyon, and after two nights there, we will go on to Joshua Tree National Park, and then back up the California coast.

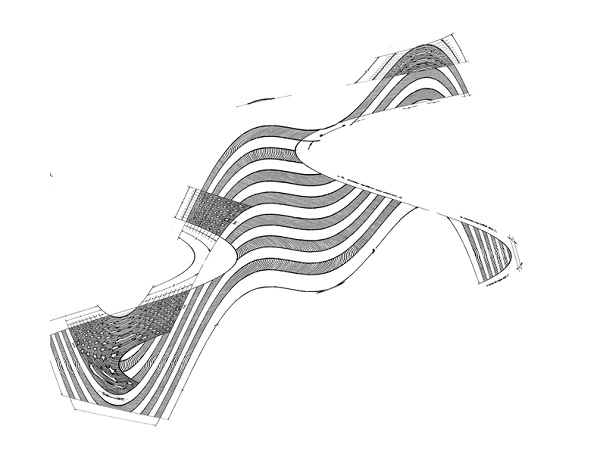

Illustration by Laura Genes

Driving up to the Canyon at sunset, pink clouds fill the sky, and go so low and even that the earth seems to end a mile up. We are in a state of mild panic, or altitude-induced hypoxia. Is this the Canyon? Can you just drive off the edge of the canyon? Or off the flat edge of the earth? The illusion gives way as the night falls and we enter the park.

We make our way to the campsite in the dark. We cook food over a fire made from the wood they sell at the Canyon General Store, and the smoke coats everything--the small, skewered tomatoes and rounds of sausage; corn still in its husk--in an oily, black layer. We eat it anyway, taking shots of tequila to warm ourselves.

In the trailer after we eat, the small yellow light overhead hits the curve of her hipbone just so. It butters the landscape of her chest, and the hollow of sternum, belly button, place where thighs round into each other, are deep dark in shadow. Somehow we fit our bodies into sex in the small space, with the window open to the night. Be loud for me, she says, her face concentrated and stormy above mine. I obey. In the morning, we warm water for coffee and bathing our hands, faces, black-soled feet. And then we set out to see it.

The Canyon, of course, looks just like the pictures. The pictures, of course, capture nothing of the feel: what it is to be immersed in its red pigments. The scale. What it is to stand at the edge, a step away from death.

The rigid, outermost layer of rock on our planet is broken into eight major tectonic plates. Where plates move against each other, they incite earthquakes and volcanic activity, and create mountains and deep ocean trenches. When the Kula and Farallon plates of the Pacific slid under the North American plate, they pushed up land and stone to create the Rocky Mountains. This same movement raised the Colorado River basin, and rerouted nearby bodies of water to dramatically increase its volume.

The Colorado River flowed down from the basin with a new power, and carved a gash a mile deep in the Arizona rock. Erosion expanded the gash to, at its widest point, 18 miles across. The Grand Canyon is a diorama of geological time, showing 2 billion year-old schists and granite at the bottom, and moving layer by layer forward in time to the 230 million year-old limestone at the rim. At points along the rim, you can still catch glimpses of the Colorado: jade-green crooks and elbows of river at the nadir of the cut rock.

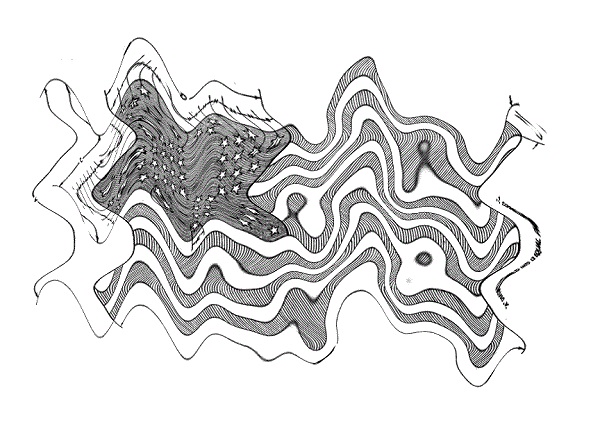

Illustration by Laura Genes

We walk the south rim. Something in my chest rises up; I keep taking breaths and holding them high. We walk so long the soles of our feet ache. I recall a cartoon about a weary Paul Bunyan dragging his axe and carving up this ground. I need to keep seeing the river around the next bend.

The red makes me awe. The green, the river, this water, makes me want.

It is the same feeling I’d had meeting her at the cafe where she worked part-time as a waitress. Her hair was cut short, and she wore a white t-shirt, jeans, a black half-apron. The sleeves of her shirt were cut wide and rolled, a take on James Dean.

I peeked at the tops of her small breasts as she bent to refill our coffee, and down her wide sleeve when she raised her arm to brush back her hair. Was the side of her bra mesh, or lace? Were her underarms smooth, or did she let soft fur grow there? Any answer would have been something to celebrate: I simply needed to know.

And so with the river: desire flared in my chest and held me breathless.

Like most love stories, this one ends. The daily grind of life together up close, of minds that fit well three days a week but not seven, of her need for noise and action and my desire for quiet and concentration, pull her away from me. She used to turn towards me every night to bind ourselves together in sleep, leg over leg, arm over waist. It was comfortable in August, but it is somehow too hot, now, in November. So, I roll away, too, tortured by the proximity of her skin and the warm, animal scent of her, near enough to reach but untouchable. We go on like this all until it is spring, when I ask her to leave, furious at the task of having to turn her away from what I want, from what she won’t admit she doesn’t.

And so, she leaves. I am left, with the problem of wanting.

There are only two ways out of desire: like Zorba, you can gorge on the cherries til you fall sick and sleepy under the tree, and, by overindulgence, cure yourself of the wanting. The other way is to want someone or something else.

So I buy a car. I buy a sleeping pad and a small camp stove. I cut reflective foil to the shapes of my car windows for privacy, and I drive to Utah for the weekend. When I get to Saint George--the last stop of civilization before you reach Zion National Park-- it is 110 degrees of dry heat outside, and the white spires of a Mormon temple sparkle like a mirage. I set up the car next to a park, the banal sounds of teenage boys playing ping pong on the courts til midnight pulling me in and out of sleep.

I am here because I know now that what Freud called the life force, the libido, can be turned to the natural world. I will fall in love with the Virgin River that runs through Zion National Park. It has carved a gorge twenty feet across creating two thousand-foot high vertical rock faces, and it runs between them with only rare respites of sand or shore along its course. I am going to hike four miles through the cold water, shallow this time of year, and admire the flat, grey rock walls, striped with black patina that looks like spilled paint. I will gaze up when the sun, at 11 or so, finally becomes visible in the narrow strip of sky overhead. I will fondle the hanging gardens of fern and moss that attach to the face of the rock. I will walk carefully in this water, feeling the stones under my feet shift with my weight.

If you are a woman, and you don’t give your life to another woman, or a to man, or to a child whose mouth or hands will always be at you, you can do this instead. Promise your body to the land, to the red dirt. Give your heart to the water.