David Lansdowne

Oatmeal is a Vibe !

ISSUE 61 | SENSE AND SENSATION | FEB 2016

Once, I had the spooky experience of passing out. On my way down, I passed through a partial consciousness that had three stages:

- Fear of Death

- Retreat to Nihilism

- Overwhelming curiosity about future sensations

Thinking about this reminds me of being online.

And that gets me thinking about DJ Khaled’s wonderful Snapchat epic where he gets lost at sea at night on a ski-doo:

In the face of imposing uncertainty, his mantra is always to investigate the subsequent moment.

“It's so dark out here. We don't know where the hell we at, but the key is to make it.”“The key is never to give up, it's not easy to win, I know tha-”

His videos suspend resolution mid-sentence by abruptly cutting to the next video. Snapchat has length limitations and Khaled is probably taking excerpts from longer reels, but the format really lends itself to his refreshing attitude towards uncertainty - instead of obsessing over a thought, he lets another in.

“The key...is NOT to drive the jet ski in the dark.”“It's so real out here smh. The only reason you see anything right now is 'cause I got the flash on. We will succee-”

His relentless, therapeutic repetition bears a resemblance to Eve Sedgwick’s description of Silvan Tomkins' writings on affect theory, in which

“ ...a potentially terrifying and terrified idea or image is taken up and held for as many paragraphs as are necessary to “burn out the fear response,” then for as many more until that idea or image can recur in the text without initially evoking terror.”

DJ Khaled sure burns out my fear response! Lost at sea, he continually restates his feelings and thoughts about the problem until optimism and insight win out and he finds a solution. It’s a fun, generous display of self-soothing made in front of millions on an uncharted media platform, and his calming influence extends even to the app itself. Snapchat, a truly terrifying image-machine, is taken up and held by an entertainer who knows the value of a smiling face and the occasional primary-colored tracksuit.

According to Wikipedia, Khaled is a Miami-based, “record producer, radio personality, DJ, and record label executive.” He joined Snapchat last October to promote his new album, “I Changed a Lot,” and the ski-doo episode went viral in December. He’s been a mainstay of the app ever since, turning out funny and inspiring videos on a daily basis.

His distinctively nurturing demeanor, penchant for filming himself putting on and taking off shirts, and dominance as a mainstream impresario of the adolescent imagination remind me of another children's entertainer notorious for frequently changing between colored sweaters:

D J K h a l e d

M R R o g e r s

Mr. Rogers was a mainstay at PBS for 32 years, from 1969 to 2001. The year he passed away, 2003, was the same year DJ Khaled got his own show on public radio.

Although they couldn’t be more different stylistically, their acts share a similar two-part structure. Rogers split his time between talking to his audience directly and orchestrating an elaborate fantasy neighborhood full of royalty, magic, and adventure. Following the trolley from the “adult rules” of Rogers’ living room into the “kid rules” of the diorama landscape allowed children to animate the lessons from their conversation within an engrossing fantasy space with the assurance that Rogers would be there when they got back. In much the same way, Khaled talks to kids directly about his “Major Keys” on Snapchat, and then releases them into energizing, fantasy-enabling rap albums populated by an ensemble of headlining rap stars.

It seems safe to assume that he developed his charismatic combination of direct dialogue and ensemble rap during his decade as a DJ on WEDR Miami. The timeline of this development was also fairly similar to that of Mr. Rogers’. During the 15 years preceding the debut of Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood on PBS, Rogers worked out the characters and settings that would go on to populate his fantasy landscape. While working on The Children’s Corner at WQED, he created King Friday XIII, Curious X the Owl, Queen Sara Saturday, Henrietta Pussycat, and Daniel Striped Tiger. He also discovered that wearing his signature Keds sneakers enabled him to move more quietly behind the sets than standard dress shoes could. After CBC tapped him to develop his first show, Misterogers, a production design team from the network helped him perfect the Eiffel Tower, The Castle, and the Trolley.

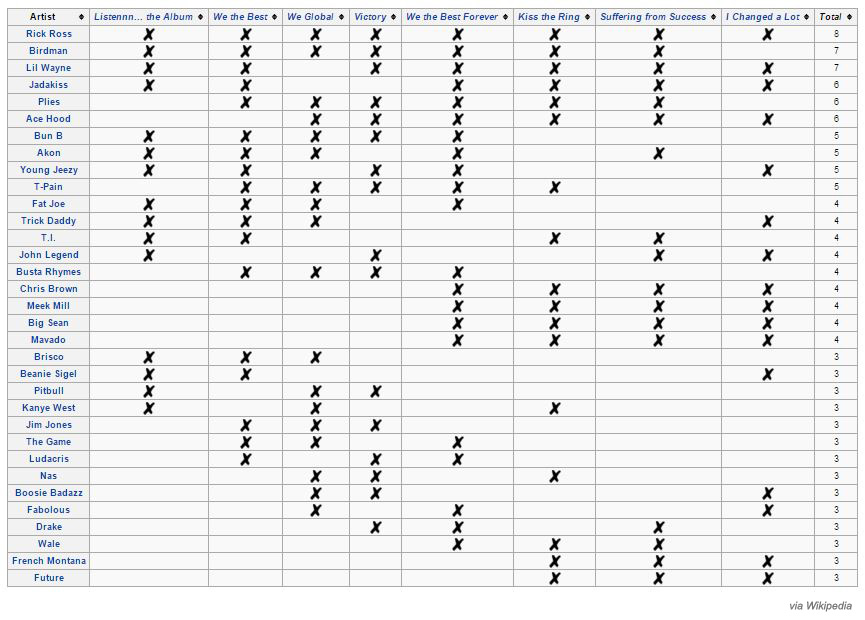

During the 13 years DJ Khaled spent on the air at WEDR, he built a reliable host of collaborators who have continued to work with him on most of his albums:

This February, he launched a weekly radio show, “We the Best Radio,” on Beats 1, the radio station that ships with Apple Music on every new iPhone. Every show features a guest host – the first week was Future and the second was Nas. Hopefully, the parallels with Rogers’ career will continue and he’ll stay there for some time.

Incidentally, Rogers has been the subject of a decades-long theory that he was a sniper in the military before starting his show. His long-sleeved sweaters, according to the theory, were necessary to conceal the tattoos covering his arms and torso—one for every enemy combatant he killed.

Mr. Rogers played himself onscreen because he thought kids could “spot a phony from a mile away.” Despite relentlessly insisting, “Don’t ever play yourself,” Khaled also seems very genuine. The accessibility of his message makes interpretation totally unnecessary. That said, his many catch-phrases are enchanting, and their relational logic is so airtight that it’s fun to think through schematically.

His label “We the Best Music” connotes simultaneous self-love and self-aggrandizement. Sounds like “We-The-Best music” and “We the best music” respectively. It’s self-evident when you watch him that personal happiness is inextricable from professional success: his status seems like the natural outcome of his positive attitude, and his positive attitude seems like the natural outcome of his status. But by constantly framing all success as the outcome of applying his “keys” as opposed to his own creative exceptionalism, he flattens the customary us/them exclusivity of celebrity status.

Success is available to anyone applying the keys—so long as you're following him (“You smart, you loyal”) “You” are absorbed into “We the Best”, a royal We constituted by all the “Fan Luv” that Khaled gives and receives. The inclusivity of We the Best relocates They from the usual us/them distinction onto anyone who would stand in the way of the people’s inherent right to life, liberty, and wins. When he says, “You do know, you do know they don’t want you to have lunch. I’m keepin it real with you. So what you gonna do is have lunch,” it’s hard to have much sympathy for Them.

Khaled’s live-feed demonstrates how, in We the Best Music, consumption and production are in constant exchange. His signature song-opening declaration of “Another One” (as in another hit single) also sounds like stern encouragement from a personal trainer. For a follower/listener, properly consuming another one means identifying his relentless production as itself one of the "Major Keys”. When you buy one of his songs and it opens with him declaring “Another One”, now you gotta do Another One. By listening to another and doing another, listening then doing, you gradually learn the keys. The more keys you know, the more you win, and that’s what he means when he says: “Knowing is better than learning.”

And, ideally, applying his keys FTW removes you from the closed loop of

- Fear of Death

- Retreat to Nihilism

- Overwhelming Curiosity about future sensations

…returning you to a happy presence of mind.

“Just Know.”