Kate Williams

Waffle House: A Strange American Dream

ISSUE 60 | SEE AMERICA | JAN 2016

In Waffle Houses across the southeast, the second rush begins around 2 a.m. Bars close and spill their tipsy patrons out into Ubers and Lyfts and city buses, and they travel in droves to the nearest yellow-signed building. They’re easy to find: drive along any interstate in the region and you’ll likely see one or two at each exit. (Atlanta alone has more than 250 locations.) The customers smash buttons on the jukebox, order their hash browns “all the way,” and dance in the aisles until waitresses bring their platters of breakfast foods, served on ceramic plates with a decorative brown border. They pack into booths, spilling out onto the floor with laughter or slurring or both. After an hour or so, they stumble out and wander home, bellies full of grease and salt.

I have been this customer more times than I care to admit. In high school, we’d go to Waffle House after football games or illicit backyard parties or when we were bored. It was a crucial halfway point between events and our homes, where we could sop up all those Bud Lights, gossip, try to find out if Sam or David or Brandon liked us. (They didn’t.) As we grew older, we’d show up to the Athens or West Atlanta location in the middle of the afternoon on New Year’s Day, praying that hash browns would soothe our stomachs and unlimited coffee would cure our hangovers. Yellow paper Waffle House hats optional.

The first Waffle House had only counter seating, which has been reproduced in the Waffle House museum in Avondale Estates, Georgia. A few benches along the side wall served as a resting spot for customers who just wanted a coffee.

My standard order is a pecan waffle with a side of raisin toast, both of which I slather with whatever brand of salted fake butter they bring to the table. I especially cherish the meals when the toast shows up “kinda burnt” — the copious sugar in the bread caramelizes to make a salty-sweet treat. Perfect alongside nut-studded malty waffles, which are also always better when they’re served extra crispy.

Everyone has their own personal Waffle House. Mine is Unit #1000 on East College Avenue in Avondale Estates, GA. It opened in the ‘90s, right across the street from the very first Waffle House, which was sold in the ‘70s, operated as a mediocre Chinese restaurant, and later turned into the country’s only Waffle House museum.

That very first Waffle House opened over Labor Day weekend 1955, the same year Roy Kroc joined McDonald’s and transformed the American dining scene. Its founders, Joe Rogers, Sr. and Tom Forkner, had left careers in chain restaurant management and real estate, respectively, to open what they later deemed “A Unique American Phenomenon”®. The plan was that Waffle House would serve breakfast foods, primarily waffles and hash browns, plus diner staples like patty melts and ham steaks, 24 hours a day, seven days a week. It would be a friendly restaurant, offering “GOOD FOOD FAST”® at cheap prices. They say they had little intention of expanding.

Waffle House originally made all of its products from scratch, with three exceptions: Post cereals (above), Heinz ketchup, and Coca-Cola sodas.

But Rogers and Forker had hit a sweet spot. By 1957, Rogers and Forkner had opened a second location; by 1961, there were four in the Atlanta area. During the 1960s, Waffle House became a franchise and growth exploded. By the end of the 1970s, there were over 400 Waffle Houses across the Southeast. Today, there are 2,100 locations in 25 states, which means you can now eat the same Waffle House waffles in Goodyear, AZ, Austinberg, OH, and Key West, FL.

And each of those locations serves a lot of food.

"If you laid all of the Smithfield Bacon that Waffle House® serves in a year, end-to-end, it would wrap all the way around the equator! That’s over 25,000 miles of a Bacon Belt!! If you could stack all of the Sausage Patties that Waffle House® serves in one day on top of each other, it would be nearly twice the size of the World’s Tallest Building, Burj Khalifa in Dubai or four times the size of the Empire State Building! Now that’s a tall order! If you poured all of the cups of Coffee that Waffle House® serves in one year, it would be enough to fill nearly 8 Olympic swimming pools!"

This exclamation point-filled braggadocio is typical of the chain, which is impressively proud of its product. Waffle House has gotten into Twitter battles over the superiority of its American-style waffles over Belgians and has trademarked its own Waffle House-themed songs. Its website has a ticker that will tell you just how many bacon strips, hash browns, waffles, coffee cups, and hamburgers the chain serves every minute. These dishes, the chain brags, are all made from ingredients anyone can find at the grocery store: Jimmy Dean Sausage, Springer Mountain Farms chicken, Heinz sauces, Coca-Cola sodas, Minute Maid Orange Juice, and Sara Lee desserts. Its factory-farmed bacon comes from the same factory-farmed pork formerly repped by Paula Deen. “You too, can eat Waffle House-quality ingredients at home,” the website suggests.

Even today, much of the seating at Waffle House allows for an easy view of the kitchen, which gives the customers an inside look at how the grill cooks communicate.

Its name-brand ingredient aesthetic is a throwback to the glory days of prepared convenience foods in which Waffle House came of age. As a journalist for the Washington Post wrote at the time:

“The 1957 housewife can prepare three meals a day for a family of four in one hour and 20 minutes. Her mother spent nearly six hours daily doing the same job. These two facts ... represent a modern miracle in the kitchen, probably the biggest let-up in kitchen chores since man discovered fire and put woman to work cooking over it.”

Many of these convenience items are still familiar. However, unlike those 1950s housewives, Waffle House originally made its food from scratch. When I toured the Waffle House museum this December, a Waffle House communications associate named Katie told me that in the '50s, there were only three items not made in the restaurant’s small commissary kitchen: Coca-Cola, Heinz ketchup, and Post cereals. Back then, Joe Rogers, Jr. and “Miss Maggie” would come into the back commissary kitchen at five every morning and prep for all of the restaurants “until things got too big,” she said.

Today, Katie continued, “with the presence of huge food companies, employees luckily don’t have to do all of that work anymore.” The toppings for the hash browns are still all made in each location’s back kitchen, but just about everything else comes from large food distribution companies.

Waffle House no longer has a separate grill for burgers. Today, everything from the hash browns to the Texas Bacon Patty Melt is fried on a grease-laden griddle.

Anthony Bourdain recently highlighted Waffle House on his CNN show, Parts Unknown, when he and local celebrity chef Sean Brock made a late-night pilgrimage to a location in Charleston, SC. Both clearly intoxicated, they split a pecan waffle slathered in fake butter and fake syrup, just as I did on those high school nights. Bourdain immediately falls in love:

“[Waffle House] is indeed, marvelous. An irony-free zone where everything is beautiful and nothing hurts. Where everybody, regardless of race, creed, color, or degree of inebriation, is welcomed. Its warm yellow glow a beacon of hope and salvation, inviting the hungry, the lost, the seriously hammered all across the South inside. A place of safety and nourishment. It never closes. It is always, always faithful, always there for you.”

Why do so many of us fall in love with the cheesy chain, in spite of our best intentions? It certainly has little to do with the quality of the food. Likely, Waffle House fervor has much more to do with this idea to which Bourdain hints — through its marketing efforts, restaurant aesthetic, and simple, easy-to-love menu, Waffle House taps into a populist nostalgia that, while Southern at its core, is a uniquely American phenomenon.

Scattered, Smothered and Covered

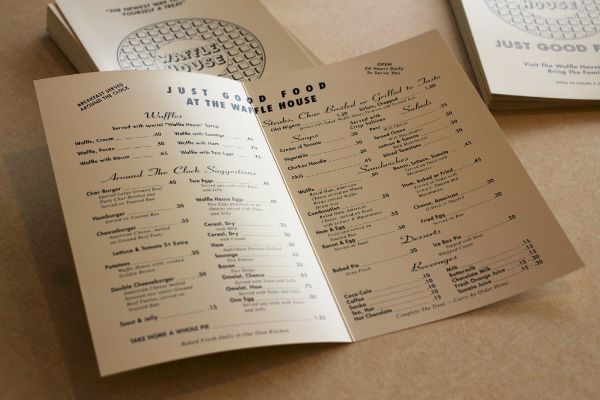

Waffle House’s original menu isn’t too different from the colorful laminated placemats at the chain today. There are waffles, of course, and eggs, toast, burgers, and coffee, all served 24 hours a day. One item, however, is conspicuously missing: hash browns.

While I’m not sure when hash browns made their debut, they weren’t given the full Waffle House treatment until the 1980s. That decade saw the addition of the first trademarked menu items: “Bert’s Chili,” “Lib’s Patty Melt,” and hash browns served “Scattered, Smothered, and Covered.” Today, you can also order your potatoes “chunked,” “diced,” “peppered,” “capped,” “topped,” and “country.”

If you’re confused about what any of these names mean, you’re not alone. You’ve just never eaten at a Waffle House. “Scattered” hash browns are thrown on the grill willy-nilly instead of being fried neatly in a ring. (That’s what you’ll get if you simply order “hash browns.”) Order them “smothered,” and you’ll get sautéed onions. “Covered” will get you melted slices of Kraft singles on top. “Chunked” indicates diced ham, “diced” adds grilled tomatoes, “peppered” equals jalapeño peppers, and “capped” denotes grilled button mushrooms. “Topped” hash browns are topped with a ladleful of “Bert’s Chili” and the “country” version gets sausage gravy. Brave souls who don’t care for appearances can order hash browns prepared “all the way,” with, naturally, all the toppings.

In the Anthony Bourdain video, Sean Brock insists that “you can’t go all in, [even though] you want everything.” He continues, “There’s a balance. When you find your balance, you memorize it. I go scattered, smothered, covered, chunked.”

After taking a hash brown order, whatever it is, the server will take the few steps required to get to the open kitchen and shout the items to the grill operators. Yes, shout. Waffle House has never used tickets. Instead, the staff communicates with a unique shorthand devised for supreme efficiency. “Scattered, smothered and covered” is only the beginning.

Reprints of the original Waffle House menu are available as free souvenirs from the Waffle House museum.

The grill operators keep up with orders using another unique chain-wide system of “marks.” Cooks place packets of condiments and/or small pinches of hash browns on each plate in specific locations and at specific orientations. Each of these items indicate a specific dish. Andrew Knowlton explained the system in Bon Appetit:

“For a sausage omelet, say, you would grab a plate and place a horizontal grape jelly packet right side up at the three o’clock position. For a Texas Patty Melt, you place a right-side-up mayo pack in the center of the plate with two slices of buttered Texas toast and two slices of cheese. And hash browns? That involves putting a few shreds of potato on the plate with a bit of each topping requested. And that’s an easy order.”

It takes time, lots of time, to learn the lingo. Kelly, another communications associate and Waffle House museum tour guide, told me that she’s been working there for 11 years and still “doesn’t know what the cooks are saying most of the time.”1 But, because the kitchen is open and because some of this language is printed on the menu for all guests to read, there is an open invitation for all guests to learn it. Indeed, writes food scholar Katie Rawson in her essay, “America’s Place for Inclusion,” the Waffle House language, while obscure, is inclusive and transparent:

“Waffle House language reflects this idea of special knowledge. On the menus, “scattered,” “smothered,” and “covered” are defined explicitly — the hash browns are spread out, grilled onions are added, and a slice of cheese is melted on top. While other ordering language is not printed on the menus, the open kitchen layout allows customers to listen and learn the language of the staff. The customers get to be included in a special linguistic code, a mode of belonging that blurs established modes of interaction between customers and workers.”2

But the menu is not the only way in which Waffle House brings its customers into an inner circle. There is also the jukebox.

Waffle House Doo-Wop

Every location gets a yellow and brown jukebox that usually sits right next to the front door. It used to be accompanied by a push-button cigarette vending machine; these disappeared with the smoking section in the early 2000s. Half the songs in the machine are friendly Americana and 1950s doo-wop, but there’s no real reason to play these.

Each Waffle House has a jukebox, and each jukebox comes programmed with the company's in-house Waffle House tunes like "844,739 Ways to Eat a Hamburger" and "Waffle House for You and Me."

The original Waffle House logo was designed with letters that were supposed to look like drizzled syrup. Instead, they gave off more of a crappy haunted house vibe. The lettering in today's logo is looks like clean yellow Scrabble tiles.

The most recent video is far more elaborate — it features a young, white, bearded rapper getting psyched for Waffle House on Christmas Eve. He name-checks other rappers who love the chain (DMX, Cee Lo, Dwight). Shots of mustard and syrup are shot in slo-mo, and the resulting visuals are glossy, hip, and clean.

It’s not hard to view these videos as a play for the eyeballs of a younger generation. In 2010, Waffle House’s website went through a dramatic redesign, at which point, Rawson posits, the chain increased its online focus towards the customer. The updated website retains a kitschy, Americana vibe, but it’s fairly modern, with links to “fun facts” and pop-up timelines that make it easier for newer, more computer savvy customers to interact with the company. More recent additions to customer outreach include a highly active Twitter feed that shares little-known waffle trivia and re-tweets fan photos.

A collection of tee shirts hangs on the wall at the Waffle House museum.

Customer contributions are a bit more entertaining. My favorite is from Bill, a visitor from Sussex, England, who was trying to drive overnight from Miami to Virginia. “Yes, I was an idiot and in the wee hours of the morning I made my first visit to a Waffle House,” he writes. He describes his fellow patrons as “chaty [sic] and friendly in only a way that I now understand Southern Americans to be.” Inside, he meets a server, whom he describes as “cute-extremely,” and he ends up following her home to her “trailer type home.” They chat for a while, and then, inevitably, begin making out: “I don’t think I’ve ever had such lip movement since my electric toothbrush shorted out!” He spends the night and returns to Waffle House the next morning, where he watched her “skilfully [sic] scramble some eggs. There is an amazing gyration in a petite girl scrambling eggs.” Later, he drives north and stops in at another Waffle House for diner. He once again gets to chatting with a “raven haired” server about his previous Waffle House experience. After she tells him that “us Tennessee girls are MUCH friendlier than the girls from Florida!” he ended up staying in the town for four days. “All the while,” he writes, “I filled up on a warm, sweet, and friendly southern hospitality experience of eating waffles!”

Bill says that he now visits Waffle House every time he comes to the U.S. To him, it is the most defining and important feature of the country. He believes that Waffle House represents the epitome of American friendliness and hospitality — exactly how the company wants to be seen.

When Waffle House upped its social media efforts, the company appeared to mimic the style of the Waffle House Shrine. Its Twitter feed, Facebook page, and Instagram pictures are more polished, spell-checked, and wholesome than the shrine, of course. Yet even behind the feeds’ corporate sheen, it’s clear that Waffle House values the narratives of its fans. Even today, the company does little advertising; much of its fan base is generated by word of mouth, which can inspire tall tales. Waffle House doesn’t discourage them.

“Waffle House has no locks”

It is a well-established “fact” that Waffle House “has no locks.” This idea pops up everywhere, from Yelp to the Waffle House Shrine — even the tour guides at the Waffle House museum. It’s not true.

Waffle Houses do close, sometimes. When they do, it’s most often during major storms or other natural disasters. Closure is a worst-case scenario. It is, in fact, such a significant event that the U.S.’s Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) pays attention. Since 2011, FEMA has, in addition to other metrics, used what they call the “Waffle House Index” to measure the strength of storms. Level Green means area locations are open and serving a full menu — everything is good. Level Yellow indicates a loss of power occurred; regional Waffle Houses are likely operating on generators and serving a limited menu of items that do not need refrigeration. Level Red is bad. It means a Waffle House is closed, indicating severe damage in the area. “If you get there and the Waffle House is closed?” FEMA administrator Craig Fugate told the Wall Street Journal in 2011, “That’s really bad. That’s where you get to work.”

Waffle House beefed up its disaster response in 2005 after Hurricane Katrina. During that storm, seven of its restaurants were destroyed and around 100 were shut down. Those that remained open served as a beacon of hope to area residents. A friend emailed me the following story:

“A few days after Katrina hit, we drove down back to our house in Diamondhead, MS to clean up and assess the damage. It was over 100 degrees with humidity at times. There was no running water or electricity (i.e. no air conditioning). The heat accelerated the decomposition of food to the point that I had to hold my breath [to keep] from gagging.After a few days, everyone was pretty gross from sweating and not properly bathing. Neighbors I had only seen in business suits were cleaning things in their yard half-naked. Then word went around that the local Waffle House shipped in a bunch of generators and was opened for business with full service — air conditioning, eggs, bacon, coffee. When I arrived, there was a sea of people waiting in the Mississippi heat for their turn to get inside the Waffle House. It was a beautiful to see the whole neighborhood there. No one minded the wait and everyone had the biggest smile.”

Since then, the company has developed a manual specifically for disaster response, bulked up on portable generators, and added mobile recovery command units to dispatch to affected areas. “It’s good, neighborly behavior,” Katie told me. (It’s also highly profitable. Managers told the Wall Street Journal that sales can double or triple during a disaster.)

Openness is a common theme in Waffle House branding. Even during the 1960s, company execs spun a radical narrative of inclusion, claiming that the restaurant has always been open to everyone, no matter a person’s race or creed.4 An article in the Atlanta Daily World from January 1964 reads:

“A demonstration at a restaurant Thursday evening resulted in [12 people] being served. The sit-in demonstration took place at the Waffle House at 972 Peachtree St. NW. The demonstrators sat without service for about an hour before the manager, Randolph Chavers, entered his restaurant and told his head waiter to serve the young people. Up until this time the head waiter stated that the establishment was closed and he wasn’t serving anyone. He said he was sending for the manager who would have to make a decision. … When asked if it was policy to serve everyone, the manager replied, ‘as long as they come in orderly and not cause any disturbance, they will be served.’”5

This tale was re-told in 2004 in a profile on Rogers, Sr, in the Atlanta Journal-Constitution (AJC). In it, he claims to have personally diffused the protest and invited all of the diners inside to eat. He told the paper that, until that point, “no black person had asked to be seated at a Waffle House,” so sit-ins had been largely irrelevant to the chain. (I somehow doubt the truthfulness of this claim.) This statement came at a crucial time for Waffle House. During the 1990s and early 2000s, the chain was hit with over 20 different discrimination-related lawsuits. Most of the lawsuits involve white employees refusing to serve or harassing minority customers. One suit, in 2005, included complaints that servers allegedly announced that they didn’t have to serve African-American customers, and when they did, they served them fly-infested food and directed racial epithets and other verbally abusive language to the customers.

Rogers’ response to the growing lawsuits was to mostly just shrug his shoulders. He told the AJC he was “upset at first. … Then I realized it was mostly a result of us getting so big.” He continued by adding that “nondiscrimination has always been, and continues to be, one of the company's core policies.” This deflection of racial tension, Rawson writes, “removes the struggle and waiting from the Civil Rights protest. … It places Waffle House squarely on the side of social progress, instead of addressing the contentious negotiations of public space in Atlanta restaurants in the 1960s.”

It’s also a common practice. Remember back in 2013, when Paula Deen was taken to task for her use of racial slurs and dreams of a plantation-style wedding for her brother Bubba? Her response, while apologetic, was to say that “things have changed” and “that’s just how things were in the 1960s in the South,” when she used the n-word in her regular vocabulary. She understood how her vision for the wedding could be “misinterpreted” now, and ultimately decided that she wouldn’t want to have “impressive middle-aged black men” serving guests as they did “before the Civil War.” She reports these events and thoughts in her 2013 deposition for a discrimination lawsuit against her and her brother in a tone that suggests that all of these ideas are just common sense; these ways of thinking are just a matter of course in the South. Again, she seems to just shrug her shoulders and move on.

Like Deen, it is of utmost importance for Waffle House to position itself as racially inclusive, despite evidence to the contrary. Such a position brings the restaurant into 21st century America; at the same time, its deliberately hokey concept appeals to a deeply Southern nostalgia. Waffle House’s claims of openness fall in line with the myth of Southern hospitality — everyone is always welcome, no matter the hour. It is this idea of hospitality that maintains the restaurant’s popularity. Waffle House’s deliberate branding as a place “with no locks” helps to create a melting pot of customers and employees, all sitting and conversing together on the side of a freeway at 2 a.m. It creates a place where foodies can dine with truckers, where customers know a secret language, where visiting Brits can meet trailer-park Southern belles, where evacuees line up for a hot meal. The grill cooks are happy to flip burgers for minimum wage, and each “unit” forms a family. The company imagines a place populist at its core, a restaurant by the people, for the people.

1 All Waffle House employees, including those who work at the corporate office, are required to work at least one shift a year behind the counter. Some work more than others. Kelly, in communications, says she can’t handle working more than a shift or two. “I’m a wuss,” she said.

2 Rawson, Katie. “‘America’s Place for Inclusion:’ Stories of Food, Labor, and Equality at the Waffle House” in The Larder: Food Studies Methods from the American South, p 234. University of Georgia Press (2013).

3 These employee comments match those told by Waffle House in its in-house magazine, Inc. (Inc, by the way, stands for “inclusive,” not “incorporated.”) The magazine, says Rawson, is “filled with descriptions of Waffle House community initiatives (ranging from sponsoring a hip-hop film festival to working with an international volunteer program) as well as biographical articles and interviews with employees who worked their way into management. The publication is one element in an array of media produced by the company to craft and promote narratives that demonstrate and praise corporate diversity and success.” It’s not all talk, though. Waffle House has both an employee stock program and an active in-house recruitment system for managerial positions. Some employees stick around for 25-30 years, Kelly told me.

4Interestingly, S. Truett Cathy, the founder of Chick-Fil-A, was a friend of Rogers and Forkner. He even developed his famous chicken sandwich in the original Waffle House, and sold it there before opening his first restaurants. Chick-Fil-A was outed in 2011 of contributing to and supporting anti-same-sex marriage organizations, as well as discriminating against gay and lesbian employees.

5 Rawson, Katie. “‘America’s Place for Inclusion’ Stories of Food, Labor, and Equality at the Waffle House” in The Larder: Food Studies Methods from the American South, p 228-229. University of Georgia Press (2013).