Eric M Gurevitch

Thinking With Sylvia Ageloff

ISSUE 55 | FRATERNITY | AUG 2015

*** Introductions ***

At 5:30 in the afternoon on April 15th, 1942, special agent R.S. Garner, F.B.I., knocked on the door of Sylvia Ageloff’s apartment in Brooklyn and interrogated her for two-and-a-half hours. Sylvia (at that time using her mother’s last name “Maslow” so as to not draw attention) was tired from teaching afternoon kindergarten class and according to the FBI report was:

greatly perturbed as to how her present address was ascertained and said that only the members of her immediate family know where she resided. She said she wished her present residence to be kept a secret, inasmuch as she wanted to forget the events of a few years ago and continue to live in peace and quiet.

In the interaction that follows, it is difficult to hear Sylvia’s voice—her words come through in the third person as they are mixed in with the highly systematic evidence-seeking tone of The Bureau, an organization she had no desire to talk to, let alone share the story of her life with. She brazenly lies to the agent, both hiding and obscuring major events from her past. At 8pm, Sylvia “said she had an engagement for that evening and could no longer talk.”

Sylvia didn’t want her voice to be heard—not by the F.B.I., not by her friends or comrades. Once the official state apparatuses of Mexico and the United States were through with her words, she had no need for them either. She never gave an interview. She never wrote an editorial.

Two years prior to the F.B.I.’s interruption, Sylvia had been going through a breakup. It was a bad breakup, which was why an F.B.I. agent showed up at her house two years later. The agent came asking about the time she had been living in Mexico with her boyfriend, a man she knew as Jacques Mornard, but the American government knew as Frank Jacson, and whose mother knew as Ramon Mercader. He had stabbed Sylvia’s intellectual idol, a man the world knew as Leon Trotsky, in the head. Trotsky did not survive.

For most of the interview, Sylvia is reserved and reluctant to indulge the F.B.I. agent. But when R.S. Garner begins to ask her about Frank Jacson, Sylvia’s distinctive words break through the official line of questioning. She is disdainful and her language is highly practiced—“She believed she was merely a ‘catspaw’ and dupe for Jacson.” Eventually, Sylvia grows tired of the agent’s impersonal interruptive interrogation, and, unwilling to indulge him any further, abruptly ends the conversation by saying “that she has not seen Jacson since he was taken into custody by the Mexico City Police, and does not know what has happened to him and cares even less.”

*** Reintroductions ***

She may have not cared to share her memory, but Sylvia was not being entirely straightforward in her statement to special agent Garner; there was one occasion after he had been taken into police custody that Sylvia saw Jacson. Three days after Trotsky died, Leandro Sanchez Salazar, the police chief in charge of protecting Trotsky and later investigating his murder, decided it would aid his investigation to bring Sylvia and her lover face-to-face again. Based on their interaction, Salazar thought he would be able to tell whether Sylvia had been complicit in the attack. With a flourish seemingly taken from a bad noir film, the interaction was scheduled just before midnight. Jacques Mornard was told he was being taken to have his bruised eye examined, and was led to a room where he found Sylvia, being held in police custody in the Green Cross Hospital, likewise not expecting him.

In the scene that Salazar paints (he admits that it is “dramatic,” although we might call it “manipulative” or “delusional”), Sylvia is in bed, already in tears, when Jacques comes into the room. Jacques is the first person to talk. Caught off guard, and faced with the woman who loved him, he cries, “Why have you brought me here? What have you done, Colonel? What have you done? Take me out! Take me out!” The police chief goads the situation forward, telling Jacques that if he really loves Sylvia, he should go and comfort her. It is now Sylvia’s turn to speak, and she, not wanting to be comforted, matches Jacques’ exclamations with her own—“Take this murderer away from me. Kill him! He has murdered Trotsky! Kill him! Kill him!” The rest of the scene unfolds in a similar manner, Sylvia responding with brief outbursts to Jacques’ excuses as listed by Salazar. “All lies. He’s a hypocrite, an assassin!” “Dare to say that it isn’t true! Don’t lie, traitor! Tell the truth, even if it costs you your life.” For his part, Jacques remains silent, ignoring Sylvia, unable to look her in the eye or utter her name. All his words are directed towards the police inspector, who asks him if he has anything to say for himself. All Jacques can muster is “Nothing! Nothing! Take me out of here, Colonel, I beg you!”

Salazar, the maestro orchestrating the tableau, needs to have the final word. He turns to Sylvia and asks the question that has likely been on her mind for the past three days, “One last word: during all the time that you were together, what opinion did you have of him? Do you believe that the love which he says he has for you is sincere?” Sylvia is clear and concise in her answer, “No! This man is a traitor in love, in friendship, in everything! Now I understand that I was the unsuspecting tool of a scoundrel.” She tries to spit in Jacques’ face. As the guards escort Jacques out of the room, Sylvia yells at him, “You are a blackguard! Blackguard! Blackguard!”

Diego Rivera, Leon Trotsky and André Breton in Mexico City

*** Hauntings and Hearings ***

André Breton, the founder of the surrealist movement, with whom Trotsky spent some of his lighter moments during his final years in Mexico, opens his novel Nadja by asking:

Who am I? If this once I were to rely on a proverb, then perhaps everything would amount to knowing whom I “haunt.” I must admit that this last word is misleading, tending to establish between certain beings and myself relations that are stronger, more inescapable, more disturbing than I intended. Such a word means much more than it says, makes me, still alive, play a ghostly part, evidently referring to what I must have ceased to be in order to be who I am.

Sylvia haunted many people and was haunted by many more. Her life became tied up with the lives of others she wanted to leave behind but couldn’t—her present always determined to an uncomfortable extent by her past. When you’re haunted, words come out of you, words that aren’t yours, even when you don’t want to speak anymore. When you want to ‘move on.’ People she had no desire for kept appearing in Sylvia’s life, years after the events that would come to define her. In 1950, ten years after Trotsky’s murder, eight years after the F.B.I.’s report, the House Committee on Un-American Activities—apparently unimpressed with the words that had been extracted from her previously—issued a subpoena for Sylvia Ageloff to appear before them.

Sylvia has changed over these years, sometimes consciously, sometimes unconsciously. In some cases she is more open—admitting to having been a member of the American Workers Party, something she had denied to the FBI—in other cases she is more reserved and guarded, clearly put-off by the line of questioning.

Sylvia has kept up with the aftermath of the Trotsky assassination, but makes it clear she has a marked disinterest in it. She has cultivated forgetting. When asked by the congressional Senior Investigator if she ever found out Frank Jacson’s real name, she answers, “There was a name in the last book that came out that was written by the chief of police in Mexico. It has some other name.” She has read the latest books on her own history, but hasn’t integrated their stories fully into her own. It doesn’t matter to her that his real name was Ramon Mercader—or whatever it was—that won’t change anything. If one thing has changed since the F.B.I. interview, perhaps it was that Sylvia cared even less. Or at least has tried to.

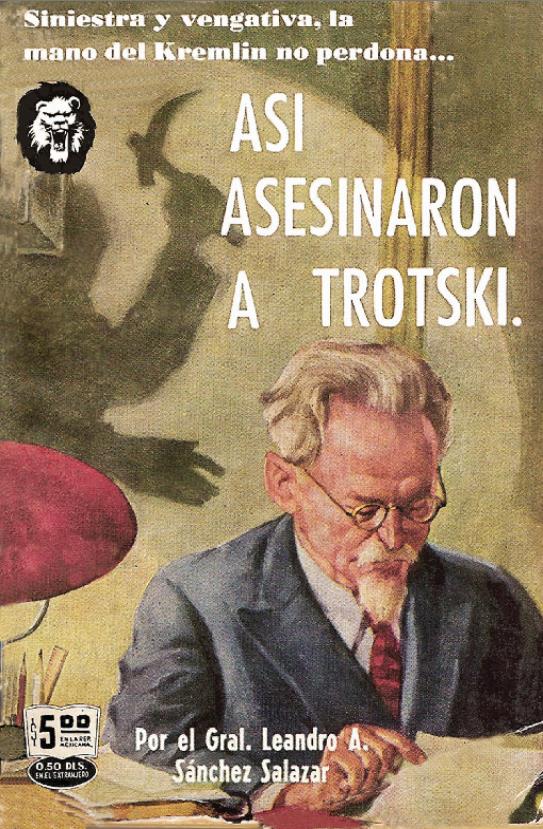

1955 edition of former police chief Leandro A. Sanchez Salazar’s account of his findings in the Trotsky murder

*** Redemption, Tragedy, Narration, and the Slogan ***

There is something about facts that demands they be strung together, and the facts concerning the lives of dead people are the most demanding. Even more, there is something special about dead Jews that draws us even deeper into the act of narrativizing. This is the conclusion the detective Lonnrot comes to in Jorge Luis Borges’ 1942 short-story “Death and the Compass.” Arguing against a theory put forward by his superior, a police-chief, the detective Lonnrot says:

It’s possible, but not interesting. You will reply that reality hasn’t the slightest need to be of interest. And I’ll answer you that reality may avoid the obligation to be interesting, but that hypotheses may not; in the hypothesis you have postulated, chance intervenes largely. Here lies a dead rabbi; I should prefer a purely rabbinical explanation; not the imaginary mischances of an imaginary robber.

H.U.A.C., the F.B.I., the Trotskyites, the Brooklyn public, all demanded a rabbinical explanation to Trotsky’s murder, and Sylvia Ageloff fit a specific role in the narrative created. Sylvia is cast in a number of roles—the damaged, dangerous woman—that were prevalent in contemporary American pulp fiction and film noir. But this is more compelling, this is True Crime. The assassination—with its ice-axe, exiled intellectual, undercover Soviet spy, and Mexican landscape—proves a ripe scene for speculation and projection, Sylvia Ageloff being one of the prime locations for hypotheses.

Looking in on his life from the outside, we also impose narrative on Trotsky’s writings. Words are said, then repeated, then repeated to others. This is the formula for a slogan, and it is a formula applied both by and against Trotsky. By the time he was exiled from the Soviet Union in 1929, Leon Trotsky had already written extensively on the slogan, trying to find the proper words for the proper time for the proper people to convey his message of permanent global revolution. Words organize people’s thought, and if one can pick the right words, they will realize their social situation, become conscious of the world around them, and act. From his exile to Mexico, slandered at home, deprived of the money, manpower, and state backing that had spread his words in post-revolutionary Russia, Trotsky redoubled his efforts at producing proper slogans and defending his prior slogans from the slanders of Stalinist theoreticians. All he had now were words, and they poured out—sterling vibrations seeking out a sympathetic string in someone’s heart. If he were alive today, snarky pundits would call this “hashtag activism.”

Consider the following three quotations from Trotsky’s corpus:

- To the toiling masses of Europe it is becoming ever clearer that the bourgeoisie is incapable of solving the basic problems of restoring Europe’s economic life. The slogan: “A Workers’ and Peasants’ Government” is designed to meet the growing attempts of the workers to find a way out by their own efforts. It has now become necessary to point out this avenue of salvation more concretely, namely, to assert that only in the closest economic co-operation of the peoples of Europe lies the avenue of salvation for our continent from economic decay and from enslavement to mighty American capitalism…[T]he slogan of “The United States of Europe” has its place on the same historical plane with the slogan “A Workers’, and Peasants’ Government”; it is a transitional slogan, indicating a way out, a prospect of salvation, and furnishing at the same time a revolutionary impulse for the future.

- Lenin brought no finished commandments from Mt. Sinai, but hammered out ideas and slogans to fit reality, making them concrete and precise, and at different times filled them with different content.

- We have few forces. But the advantage of a revolutionary situation consists precisely in the fact that even a small group can become a great force in a brief space of time, provided that it gives a correct prognosis and raises the correct slogans in time.

There are many other quotations to present Trotsky’s deployment of the concept of the slogan, and there are many other ways to have presented these ones. As they stand now, they are arranged chronologically and represent three different moments of Trotsky’s later thought.

The first is from an essay Trotsky wrote in the beginning of 1923, when Lenin was still alive (but barely), and Trotsky was fighting for power against the Troika led by Stalin. Trotsky’s words are confident, if slightly measured. He admits that slogans are transitional, existing only for the time being, while also asserting that they offer a path into a hopeful future. The word “salvation” rings throughout the passage, and the slogan is imbued with forward looking and redemptive power; it can undo current injustices.

The second quotation is from Trotsky’s book The Permanent Revolution, in which Trotsky defends and explains of his slogans “permanent revolution” and “dictatorship of the proletariat,” connecting them with Lenin’s thought, and draws on his much earlier essay Results and Prospects. Written in the early days of his exile, this book is an angry attack on Stalinist theorists, who misrepresent his work and point out contradictions in his thought by selecting quotations out of context. In this quotation, Trotsky implicitly compares Lenin to Moses, again invoking the language of salvation from the first quotation. But Lenin was a mutable Moses, able to change and adapt his slogans to fit the proper moment. Slight contradictions will be inevitable, because times change, and it is up to a powerful and honest theorist to change with them. Lenin was just such a theorist, who, with clear messianic undertones, is waiting for his true successor.

The third quotation was written in 1931 with the rise of the Second Republic in Spain and the flight of King Alfonso. It is clear here that concept of the slogan is not a mere theoretical device for Trotsky; it is a real tool by which to produce social change. Trotsky maintained a correspondence with Andrés Nin, a Spanish politician, trying to come up with proper slogans for revolutionary Spain. (Perhaps the concept of workers’ “Soviets” didn’t catch on because it was too reminiscent of “Juntas.”) In this quotation, he presents the slogan as a tool that can be operated by a small yet passionate minority, who in turn manage to create consciousness in larger sections of society and incite them to revolt. The passage, read through the lens of history, appears desperate and deluded. Trotsky, exiled from Russia, now places his hope in the revolutionaries of Spain, who he hopes will ignite a global revolution, thus redeeming him and his theory/slogan of “permanent revolution,” and possibly freeing him from his continual forced migration further from Russia. As things turned out, a “small group” was no match for a larger group with guns and Nazi backing, and the Second Republic fell, along with Trotsky’s hopes.

Strung together in the manner above, the quotations present Trotsky’s life as tragically deluded. From afar, his decline seems inevitable. Informed by his experiences as a writer and journalist participating in two revolutions (1905 and 1917), Trotsky is unable to move on, adjust his own tactics, or realize his own situation. His slogans appear, like Moses’, as cast in stone as commandments, rather than the fluid affairs he waxes poetic about. But hindsight is twenty-twenty and foresight is fifty-fifty, and Trotsky’s optimism is what has kept him a relevant figure even in today’s Left wing. Left with only his words, without state funding, Trotsky managed to inspire many people to come to his defense through his vigorous declarative statements. As the Levelers demanded in their 17th century revolution, “give losers leave to complain.” After all, when you find yourself despised and feared by both the Communist and Capitalist countries of the world, that’s all you really can do.

The reader of the past is left with quotations, and uses them to create narratives of tragedy and redemption. Quotations cannot be read on their own, each retelling restructures the plot and casts new characters. In the first chapter of The Permanent Revolution, as Trotsky defends himself against the attacks of Stalinist historians, he explains the method of analysis:

Anyway, as the French saying goes: the wine is drawn, it must be drunk. We are compelled to undertake a lengthy excursion into the realm of old quotations. I have reduced their number as much as was feasible. Yet there are still many of them. Let it serve as my justification that I strive throughout to find in my enforced rummaging among these old quotations the threads that connect up with the burning questions of the present time.

When we read Sylvia’s life and impose our narrative on it, her quotations must take the most prominent position; only then can they connect up with the burning questions of the present time.

*** A Fixation on Beauty ***

In a telling set of endnotes in their book The Saga of Leon Trotsky, the historians Harry and Marjorie Mahoney write:

507. Sylvia was 28 years of age, moderately good-looking, whose appearance was spoilt by small near-sighted eyes behind thick spectacles. She had few, if any, love affairs, but was intelligence [sic] with a pleasant personality. (Wyndham, Trotsky, Loc. Cit., p. 176.)

508. There is a difference of opinion regarding Sylvia’s personal beauty or attractiveness. One eminent Trotsky historian claims Sylvia was “a lonely spinster of a rather unattractive appearance.” (Deutsche, Isaac, The Prophet Outcast, Oxford University Press, New York, (1963), p. 483.) (What is believed to be an objective appraisal by this author, based upon a study of many photographs and interviews with people who knew Sylvia, she was a better than average good looking lady with a slim attractive figure.)

These endnotes are not unique, they are exemplary. They draw on the most authoritative scholarship about Trotsky’s life and death, and show just how ingrained speculations into Sylvia’s beauty are in the narrative of Trotsky’s murder. Even the quote-unquote sympathetic view of Harry and Marjorie Mahoney finds it necessary to say something, to make an almost-compliment, about Sylvia’s body. She was a better than average good looking lady. The rest of their depiction in the main text reveals the narrative in which they entrap Sylvia. She was “a lonesome American girl in Paris” looking for a “prince charming” and “did not want to be sensible. She was in love and wanted only to believe those things that would make that love endure and be reciprocated.” From an analysis of her body a leap is made to an analysis of her intentions and dispositions: it was because Sylvia was ugly, that she was lonely, that she started dating Jacques Mornard, that Leon Trotsky ended up dead.

This narrative is carried into novels, which when compared with the histories, make them seem rather banal. In The Man Who Loved Dogs, Leonardo Padura describes the world through Jacques Mornard’s gaze, writing:

He then focused on the freckly one with glasses, with milky skin, who hid her extreme thinness below a wide, pleated skirt and a flounced blouse, and he felt how the glass perfectly reflected back the overwhelming ugliness of Sylvia Ageloff.

And throughout John Davidson’s The Obedient Assassin, we see Sylvia through mirrors, her form distorted by the ever-present gaze at her body. She is not described as ugly outright, but is described as without fashion, taste, style, or sense—too much of a bookworm to understand men:

Sylvia put her book aside and stopped to glance at the mirror. She was fair and slim. She felt pretty until she put on her glasses, which, despite the pale blue translucent frames, weighed upon her as handicap. She occasionally dispensed with her glasses when meeting and attractive man—a dubious strategy that made the man blurry and her squinty—but she was confident that she wouldn’t be interested in anybody Ruby knew.

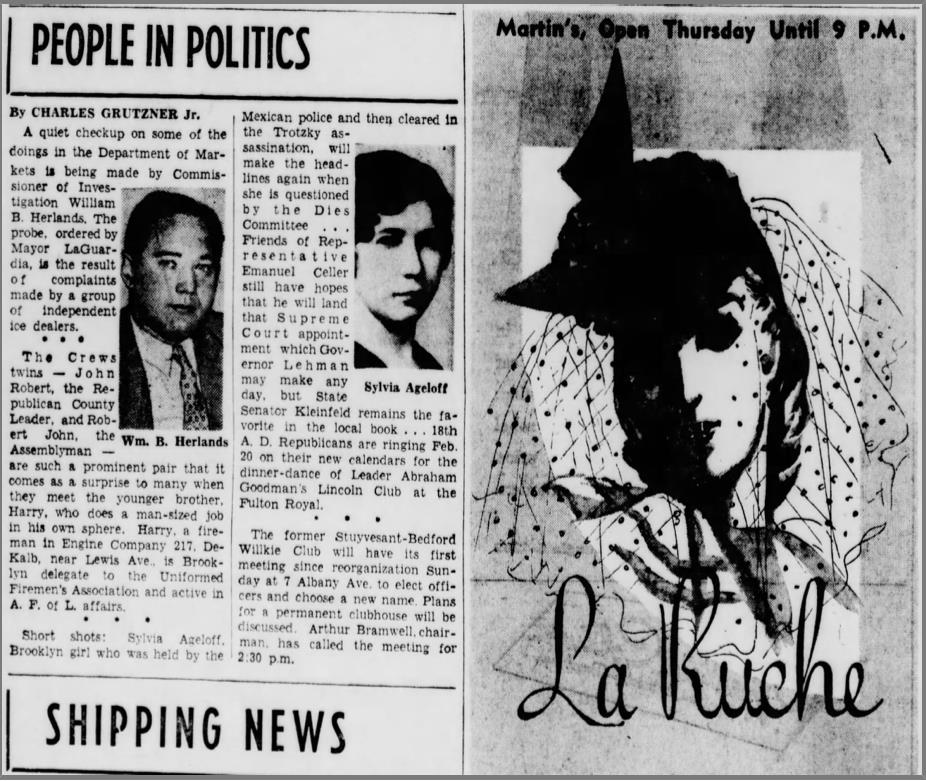

Speculations around Sylvia’s beauty appeared even before all the historical events had unfolded. On August 21st, 1940, after Trotsky had been stabbed in the head, but before he died, The Brooklyn Eagle, the newspaper of Sylvia’s home neighborhood, cast her as a typical noir femme. The headline of the paper was a simple command: Grill Boro Blond In Trotsky Attack. The paper went on to describe the situation:

Trotsky’s mystery man assailant lay in a room nearby and around the corner at the central police station police were questioning a glamourous [sic] blonde in connection with the case. She gave her name as Sylvia Angeloff [sic], 30, and her address 50 Livingston St., Brooklyn. She was said to have wept when police questioned her and sobbed, “If Trotsky dies I am going to kill myself, because I am a great admirer of him.”

It is a curiosity of circumstances that only during the events directly surrounding Trotsky’s assassination is Sylvia described as blonde.

Sylvia’s body becomes a place where different historical possibilities are played out. Every historian, every journalist, every novelist, has to focus on Sylvia’s beauty (or alleged lack thereof) in some manner, allowing implicitly anti-Semitic, misogynistic tropes to slip into their prose. Trotsky’s optimistic, forward-looking writing manifests itself in the works of those writing about him. This is history written in the counter-factual—the optative—or potential mode. If only Sylvia had been a little better looking, she would have had more self-confidence, she would have had more experience with men, she would have seen the signs. If only she hadn’t been a Jewish intellectual, she wouldn’t have spent so much time in the library, should wouldn’t be so squint-eyed, she would have stayed and found love in Brooklyn where she belonged. If only she hadn’t been a woman. If only, if only, if only. Trotsky would still be alive.

How would Sylvia have responded to these assessments? Well, we know: She was alive when many of them were written, and she responded as she had grown used to responding—with silence.

But Sylvia was forced to talk by the House Un-American Activities Committee, which asked the same questions and made the same assumptions about her body, sexuality, and intellectual competence, only with the threat of legal consequences if she didn’t answer. Sylvia is expectedly put-off and stand-offish when the question is first raised:

Mr. Wheeler: Do you feel he used you in any way?

Miss Ageloff: I think it is very obvious from what happened.

In 1950, in a public forum visible to all in the United States, Sylvia lets the ambiguities of her past shroud her situation. But years earlier, according to the notes of the police chief Leandro Sanchez Salazar, Sylvia herself had framed her role in Trotsky’s assassination in terms of being used. She is reported as saying:

I am sure now that I served as the instrument by which Jacson got in touch with Trotsky so as to kill him. I can’t offer any proof of what I say, but that is what I feel. There is no doubt that Jacson is a Stalinist and that behind him are other Stalinists whom I do not know. Stalin is the person who has the greatest reason to get rid of Trotsky. And it is I who have served as his tool.

By the time she is in front of H.U.A.C., Sylvia is more guarded. She has read Salazar’s account and has solidified her perspective. She is unwilling to grant the man questioning her that she was merely a tool. Her aggressive non-answer is insufficient for the congressional Senior Investigator, William Wheeler, who goes on to rephrase his attack:

Mr. Wheeler: Do you feel Jacson gained entrance to the house because of you? Do you feel he used your friendship to acquire the trust of Leon Trotsky in Mexico?

Miss Ageloff: I guess so. I guess if it wasn’t he, it would have been somebody else, but I guess that is the reason why they let him take them down to Vera Cruz. They certainly wouldn’t have let a stranger offer his car.

Worn down, Sylvia begins to question herself, and, like Trotsky, like the historians, enters the optative mode of history. The language here is unsure of itself and unlike the language of the rest of her testimony, which is given with the utmost confidence. Her sentences are fractured and fragmentary. I guess, I guess, I guess. But Sylvia’s alternate universe operates on different presumptions than the alternate universe of the histories, “If it wasn’t he, it would have been somebody else.” And in the end she takes responsibility in a concrete manner, “They certainly wouldn’t have let a stranger offer his car.”

There is blame to go around, and around it goes. Describing the scene August 21st, 1940, as Trotsky lay dying in the hospital, The Brooklyn Eagle quotes Sylvia as saying, “If Trotsky dies I am going to kill myself, because I am a great admirer of him.” Sylvia is shown in hysterics, unable to cope with the situation, which still remains unclear to all involved. Salazar also describes Sylvia’s condition that evening in the hospital:

Extremely nervous and inclined to histrionics, she wept constantly and assured us Jacson had used her as a means of getting into Trotsky’s house to assassinate him, and loudly cried out for us to kill him.

Once again, the language of ‘being used’ has come into the narrative. She is a tool in someone else’s plot. The accounts of the scene at the hospital from The Brooklyn Eagle and Salazar mirror each other—identical, but with one major detail reversed. In The Brooklyn Eagle account Sylvia wants to kill herself, while in Salazar’s account Sylvia wants to kill Jacques Mornard.

Both these statements can be true—Sylvia was upset by the events around her, and she could have easily expressed a wish for both her own death and the death of her lover. But the tone takes on contradictory meanings in each situation. Depending on how they choose to hear and report her speech, the reporter and police investigator depict Sylvia in a radically different light, presenting her as a radically different woman. In one version she says, He used me, kill him, in the other, I was used, kill me!

Whatever she said, whatever her intentions, these two perspectives were given in the heat of the moment. In the end, Sylvia killed neither herself nor her former lover. In the H.U.A.C. hearing, ten years later, given time to contemplate and compose herself, Sylvia makes it clear she was a thinking, rational woman and not a used body, emphatically stating:

I should say for the record though, that I never brought him [Mercader] to the house, because I felt since he was in the country illegally it was not good for Mr. Trotsky that he should ever be brought to the house. So that he only entered the house after I had returned to New York City, and Mrs. Trotsky confirmed that.

Mrs. Trotsky—Natalia Sedova—did in fact confirm Sylvia’s account, clearing her name, while describing the afternoons of tea and debates she, Leon, and Sylvia would have, and refusing to accept any possibility of Sylvia’s foreknowledge of the attack.

Still from The Assassination of Trotsky (1972), showing Alain Delon as Frank Jacson and Romy Schneider as Sylvia Ageloff

*** The Problem of Other Minds ***

Philosophers sometimes claim the problem of other minds amounts to a question of whether or not other minds exist—But things would be so boring if they didn’t. Other philosophers—a little more sophisticated than the first bunch—argue that the problem of other minds amounts to the question of whether other minds mean what they say—but really, how can people mean anything else? The problem of other minds is somewhat simpler: given that other minds mean what they say, but can never mean what I mean when I say what I say, how can I orient myself towards them? Which is less of a problem and more of a challenge, a demand placed on relations. Which is to say that the problem of other minds is not an ontological or epistemological problem, but an ethical one.

*** Reading Her Words ***

I am sitting on the sixth floor of Columbia University’s Butler Library, reading the Master’s thesis “S. Ageloff” (according to the library catalogue) wrote here eighty years ago. The thesis, entitled “A Study of ‘Prestige’ and ‘Objective’ Factors in Suggestibility in a Comparison of Racial and Sexual Differences,” was never published, but here it is, transported to me in two business-days time from an offsite storage facility in New Jersey. The index card in the back of the book says that nobody has ever checked it out. I have heard of Sylvia from other Ageloffs as they sat around the holiday table at my parents’, but I don’t know much about the woman herself. She is always mentioned in passing—nobody knew her that well, she was known of, rather than simply known. A story, a fact told to entertain and amuse, even by those related to her. As I open the beige binding, it cracks, chips of stale paper fall onto the table, but the strings holding the pages together hold strong, and I begin to read.

*** From Suggestion to Slogan ***

Although he was barred from attending it, Leon Trotsky called Fourth International into session in Paris in 1938. It is easy to forget how different our language is from the language of the past; 1938 was three years before popular magazines across the Atlantic would coin the term “teenager,” to which sociologists, psychologists and advertisers would latch onto like cuttlefish, trying to recategorize the changing world around them. For a brief period, a few months at most, both “teenagers” and Trotsky almost caught on in America. After all, both were selling revolution. Trotsky was stuck in Mexico by this time, bringing a cadre of Americans with him. Or maybe it wasn’t him; perhaps it was the murals of Frieda and Diego that brought the Americans, perhaps they were looking for a balmy climate and an escape from Fordism.

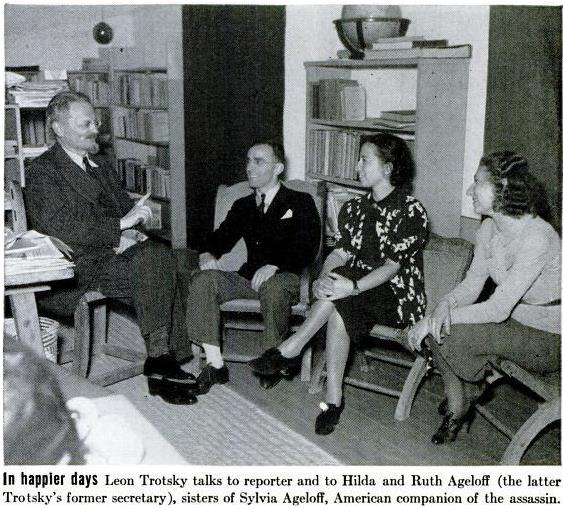

Sylvia was not a teenager in 1940, even by 1941’s standards, but that didn’t stop LIFE magazine descrbing her as Jacques Mornard’s “chief girl.” She was not looking for love or personal freedom when she was in Paris two years earlier. She was not a hysterical blonde bombshell or a lonely spinster. She was one of three Americans to attend the Fourth International.

Four years earlier, in June of 1934, Sylvia had submitted her Master’s thesis to the Psychology Department at Columbia University. Though it is short, the thesis is the most prolonged sincere public statement we have from Sylvia’s life.

By the time she was writing the thesis, Sylvia was already deep in Marxist politics. Her sister Hilda had traveled to the Soviet Union in 1931 on the pretense of learning about alternative forms of pre-schooling, and had met with Nadezhda Krupskaya, who at that point was the Deputy Minister of Education and Vladimir Lenin’s widow. Another sister, Ruth, had been guided by the young NYU professors James Burnham and Sidney Hook (who were leading radicals before they became leading figures in the neo-conservative movement) towards the American Workers Party. In a clear instance of obfuscating speech, Sylvia told the FBI agent who questioned her that “she fist became interested in the Trotsky Movement in college as an academic study, as she did not think democracy and capitalism were as ideal and beneficial as they should be.” It was college, her sisters, and their interactions with the young NYU professors, that brought Sylvia Left.

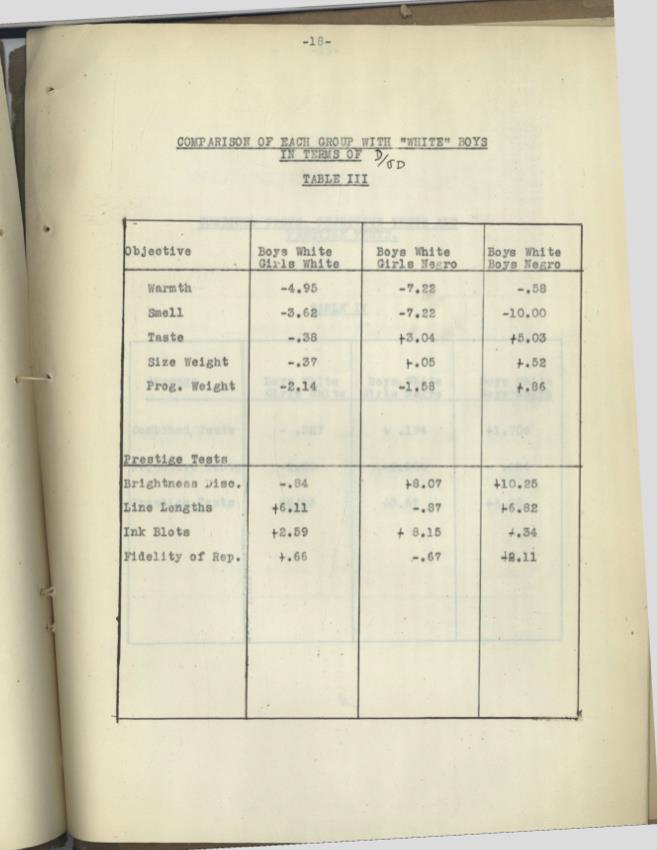

Sylvia’s Master’s thesis, “A Study of ‘Prestige’ and ‘Objective’ Factors in Suggestibility in a Comparison of Racial and Sexual Differences,” is not an explicitly Trotskyite document, but her highly rational, critical and progressive mind is displayed in what she chooses to write about. Her thesis topic (unbeknownst to her) brings together Trotsky’s invocation of the revolutionary slogan and the narratives about Sylvia’s impressionable personality that would arise after Trotsky’s murder.

The thesis contributes to the concept of suggestibility, or how the ideas of others can influence an individual. Sylvia follows a psychological tradition that posits two types of suggestibility, ideo-motor (or “objective”) suggestion, and prestige suggestion. She quotes Gardner Murphy in defining these terms: “Ideo-motor suggestibility “that is the tendency of an idea to produce and act” and prestige suggestion “which results from emotional factors in a social situation.” It is a nuanced and powerful distinction—ideo-motor suggestibility can be isolated as how easy someone is to trick. Prestige suggestion takes into account the social relationships between multiple actors, how easy is it for me to trick you.

Sylvia’s work follows the work of two female psychologists, Elizabeth B. Hurlock and Margaret Otis, and argues for the importance of considering prestige suggestibility, taking into account racial and sex differences. Sylvia argues (and proves with data) that there are significant variations in prestige suggestibility along sex and racial lines, and that the social position of the experimenter will influence her experiments in a predictable manner. In considering how a person becomes suggested to act, we need to take into account their relationship to the people around them, as well as their standing in the world.

Sylvia’s data-driven conclusion? That in resisting white authoritative figures, girls are superior to boys. She writes:

In regard to sex difference it was found that White boys are superior to White girls in their ability to withstand suggestion on the combined tests and objective tests. On the prestige tests, it was found that the girls are superior.

LIFE Magazine, Sept. 2nd, 1940

***Listening Harder***

It is in the nature of archives to give a one-sided view of things. The Trotsky archives at Harvard and Stanford have letters written from Jacques to Sylvia, but not the other way around. In the cool light of 2015, now that we know his three separate identities, it’s easy to see where he is lying to her. Preceding each lie—perhaps unconsciously, certainly distressingly—Jacques calls Sylvia a variation of “my little blonde birdie.”

There are a smattering of letters from the Ageloff sisters to Leon Trotsky and Natalia Sedova—invitations to tea and debates, thank-you notes, updates on the communist scene in New York, small jokes (“Even the New York Times is no compensation for August in New York.”)—but they offer little access to the inner lives of any of the participants.

On her return to New York, Sylvia issued a brief press release through her father’s office. Since the events in Mexico, she had been fired from her job as a social worker, a process that was played out in the local newspapers. As in all of her other public statements, she is curt, cool, and measured. For once, I’ll let Sylvia Ageloff have the final word:

I want to take this opportunity of straightening out some of the garbled reports printed in the papers. I never introduced Jacson to Leon Trotsky. This face is clearly established by the evidence that has been gathered and can be corroborated by any one who wishes to take the trouble to do that.

Furthermore, the evidence and the testimony overwhelmingly established, as the judge himself stated in his verdict, that I was the victim of a chain of circumstances of which I was entirely ignorant and over which I had no control.

I was an admirer and personal friend of Mr. and Mrs. Leon Trotsky. I have no political affiliations.

My strongest desire now is to try to put what has happened into the past. I want to try to return to the life of an ordinary citizen. I am sorry I am too ill at the present time to give any personal interviews.