Rebekah Volinsky

After Modotti, On Modotti, Of Modotti by Weston

ISSUE 54 | DEGENERATES AND DECADENTS | JUL 2015

My favorite photographer, Moyra Davey, identifies herself as more of a reader/writer than a photographer. In her essay, “Notes on Photography & Accident,” I see myself in the structure of the text: she’s collected snippets of three writers’ work on the nature of photography and its relation to accident and presents them as loosely linked haikus or meditations with her own entries interspersed. The essay is a scrapbook of others’ writing, and she builds her argument by circling through the seeds of her thoughts: Walter Benjamin, Susan Sontag, and Janet Malcolm, primarily.1 At one point, she reports William Gass’s 1977 New York Times review of Sontag’s book On Photography: “Sontag’s ideas are grouped more nearly like a gang of keys upon a ring than a run of onions on a string.”2 And, even though Davey claims to have never connected on an emotional level with the book,3 the same could be said of her own essay. In fact, I am saying it: it is a lovely way to think of thoughts.

The authors’ critical writings and personal diaries and to-do lists are considered with the same even approach, as the theories they developed have been transformed into three-dimensional characters by/to Davey over the course of the time she has spent with them. When I read her essay, a cozier version of Jean-Paul Sartre’s play No Exit comes to mind, in which Sontag’s On Photography shares a bit of tea with Benjamin’s A Short History of Photography and Malcolm’s Diana & Nikon, and interpersonal drama reverberates between the three pieces of writing as they sit in Moyra Davey’s dust-washed, light-filled room for all of eternity.

Davey writes, “I begin to wonder if it’s not the modernist paradigm kicking in, that a metadiscourse is always more satisfying: painting about painting, photographs about photography, and writing about writing. I can always be engaged by discipline- or medium-specific metaproductions.”4 Here is another personal itch I can identify with, though I would take it further. While I find painting about painting and writing about writing more engaging, too, I want to raise a call to arms in support of photographs about photography. I sense an urgent need to make some sort of claim, to layout a roadmap of hazards inherent in photography that cloaks its own discursive characteristics. Anything falling short of pushing them to the forefront seems the same as hiding.

~

In the preface to her book, Tina Modotti: Between Art and Revolution, Letizia Argenteri reflects back a glimmer of self-image to me, as well, though this one cuts: “The Modotti case has generated two curious phenomena, one for each gender. The first I call the “soul-searching process,” related to women “Tinaologists” who identify with Modotti to such a point that they even believe they are her reincarnation.”5 I suppose I’ve become a Tinalogist, in that I have indulged in researching her dramatic life course. Though, I dare say I think of myself as her reincarnation. Take a chill pill, Argenteri. I’m drawn to Tina Modotti because there is something circling around her legacy that merits Argenteri’s designation, “the Modotti phenomenon.”6

Argenteri mentions more than just two Modotti phenomena (I count at least four different ones), but the counterpart to the women’s is, of course, the men’s, “arising from the ego of men who have appointed themselves custodians and paladins of female aesthetics and beauty.”7 I would count the romantic idolization of her relationship to Edward Weston, one of the founding fathers of American photographic tradition, within in the art world as another phenomenon.8 In the recent years, there have been several exhibitions of their photographs together and a surge of writing about the two.9 The fourth Modotti phenomenon has its effect on two separate political causes: Communism and Anarchism.9 But really, it is all the same; it is just a difference in the groups that are drawn to her mythic persona, and what it is they claim she symbolizes.10

~

Tina Modotti (1896-1942) was an Italian photographer, artist’s model, actress, and revolutionary activist. She is most well known for her time living and working with photographer Edward Weston in Mexico City in the 1920’s. She went from Weston’s lover to model, to apprentice, to business and creative partner in these years until she landed as a photographer in her own right. Modotti then became politically involved and wielded her camera as an instrument of social and political change during her brief photography career, which ended in 1931. She was at that time accused of being involved in political assassinations because of her association with the Mexican Communist party and, as a result, was exiled from the country. After her departure from Mexico, she participated in various missions on behalf of the International Workers’ Relief and the Comintern throughout Europe. She spent time in Berlin and Moscow and was active in Spain during the Spanish Civil War. She returned to Mexico under a pseudonym in 1939 and died there in 1942.11 For all the accomplishments under her name, Edward Weston’s nude photographs of her elicit the most popular recognition.

~

Tina Modotti was born in Italy in 1896. She spent her years two through nine in Austria, returned to Udine, Italy, and then immigrated to the United States in 1913 at the age of 16. She lived with her family in San Francisco within the Italian emigré community for her first years in the country but then fully integrated herself into American culture. Her short stage- and film-acting career began when a newspaper mistook her for an opera actress famous within the Italian-speaking community. Her entrance into bohemian circles began in 1918, ushered by Roubaix “Robo” de l’Abrie Richey, an art student originally from Oregon. Tina Modotti never legally married in her lifetime, but Richey was the first of the men she would become “attached to,” as Argenteri puts it. They moved together to Los Angeles, where she appeared in a handful of minor roles in early Hollywood films, the biggest of which was the 1920 The Tiger’s Coat. She was often typecast as menacing Latin characters, always dark and ruled by mysterious emotion: a hysterical Mexican woman or a villainous Italian.

Robo Richey was a poet and made batiks, and he introduced Modotti to a way of living and thinking that centered around the worship of Beauty. Argenteri writes that their shared home

became the meeting place for misfit and displaced souls, who while drinking sake created in their minds a world larger and less banal than their real lives. It also became an intellectual and artistic workshop, a true thinking laboratory, where everything was perceived through the lens of their eccentricity and utopian ideals.What a relief to see that those whom we idealize and romanticize now lived under the same cloud of self-idealization and romanticization then. What would Chris Kraus think? (She’d probably buy into it.) It is clear that Argenteri sees the work of the “thinking laboratory” as the transformation of their own self-image rather than the production of new ideas. I trust Letizia Argenteri’s accounts most of all Modotti’s biographers because she approaches her subject matter with a historian’s rather than a novelist’s lens. It’s true that her subjectivity still shows, but her militant insistence on drawing her narrative of Modotti’s life from only documented records wins me over.11

It was in this crowd that Tina Modotti first met Edward Weston. He was already an established photographer at the time, married with children, though still gaining his sea legs; he had yet to fully develop his foundational Modernist aesthetic and to gain the notoriety that awaited him. Weston later characterized the group as “parlor radicals who drank, smoked, had affairs.”12 Weston entered this scene where “everyone knew everyone, and the permutations of love affairs – like an electric current – attracted one person to another” with photographer Margrethe Mather on his arm.13 She was his favorite model at the time, and she shared with him an intimate relationship. It is likely that Modotti and Weston started their affair here when both of them were committed to romantic partners. One of the earliest extant love letters from her to him is dated January 27, 1922. And, Argenteri writes that “one of the best photographs of Modotti by Weston, entitled The White Iris, is dated 1921; it shows Tina nude with her eyes semi-closed, smelling an iris.”14 Modotti soon took over Mather’s place as Weston’s favorite (often nude) model and sexual partner.

Modotti and Weston are best known for their time together in Mexico, though that trip was not the first for either of them. They had both been to the country before on their own. Robo Richey, too, had been drawn to Mexico. Mexico’s cosmopolitan and revolutionary atmosphere in the 1920’s attracted a wave of American radical intellectuals and artists “who detected a bond with the Mexican leftists.”15 Richey had gone down with his work and Weston’s in hopes of putting on an exhibit. Months later, when Richey contracted smallpox in early 1922, Modotti rushed to his side – or as close as quarantine would allow. Modotti mourned Robo Richey for a month in Mexico before returning to California. Then, in 1923, Modotti, Weston, and one of Weston’s sons moved to Mexico City.16

~

The Mexican Revolution had begun in November 1910, ending El Porfiriato, the 34-year reign of dictator Porfirio Díaz. There were several key figures whose influence ebbed and flowed, overlapped and countered each other, within the revolution – Francisco “Pancho” Villa, Emiliano Zapata, Francisco Madero, Venustiano Carranza, and Álvaro Obregón – though the common drive of the revolution was to overthrow la encomienda, an unequal, feudal-like economic system, which was a relic of Spanish colonial rule.17

~

A brief history of Mexican rule: between its conquest by Spain in 1521 and the War for Independence, which began in 1810, the dominating power was held by European-born Spanish colonists, los peninsulares, whose name referred to the Iberian Peninsula where Spain is situated. Under los peninsulares in the Spanish colonial caste system were los criollos, people of full Spanish-descent born in the Americas, and los mestizos, those of mixed Spanish and indigenous descent. Mexican Independence was won in 1821 by the criollo minority, who remained in power a century later. Now we arrive back at 1910, when the Mexican Revolution was started by liberals and intellectuals and fought for people’s economic rights – “people” here referring to the agrarian majority, los mestizos in the presiding racial-political terms. The slogans “Tierra y Libertad” and “La tierra es para el que la trabaja” do well what slogans are meant to do and succinctly convey the message of their movement.18

~

Argenteri illustrates the environment in which Modotti and Weston travelled to Mexico as being one that combined a growing national identity and cultural movement with an international kinship of populist ideals. “In the 1920s, Mexico was a country still in search of institutional and political stability, and consequently, of social and economic reform. The November 1910 revolution continued to reverberate, but whatever its political failures, it was a cultural success, not only because it inspired populist movements but also because it revealed a nation to itself, and it made clear the cultural continuity of Mexico which had survived the political fractures.”19 Mexico in the 1920s was fertile ground, and American and European liberal thinkers were flocking there as Porfirio-exiled political thinkers and self-exiled Mexican artists were returning home. Francisco Madero, the first Mexican president following Porfirio Díaz, drafted one of the main rebel plans for reform, the Plan de San Luis Potosí while in exile.20 In 1920, Álvaro Obregón was the president, and José Vasconcelos was appointed Minister of Education. Vasconcelos had, too, been abroad in America and Europe in recent years.21

In his position as the Minister of Education, Vasconcelos spearheaded a vast education reform effort that leaned on culture as its avenue for effect. Vasconcelos was inspired by Russian Socialist thinkers like Maxim Gorky and modeled his plan on that of Anatoly Lunacharsky, the Commisar of Education and Fine Arts in the Soviet Union. Vasconcelos stressed the cultural aspects of the revolution and called for “an art free of academic posturing that would be liberated from the conventional imitation of European models.”22 Vasconcelos in his government position is responsible for the well-known Mexican Muralist movement of Diego Rivera, José Orozco, and David Alfaro Siqueiros. He believed that artists had a duty to be involved in politics, and Argenteri adds in, “after all, in Mexico the painters were intellectuals whose role was analogous to that of writers in other countries.” Siqueiros’ favorite saying at the time, “socializer el arte,” makes for a great example of the atmosphere.23

~

Tina Modotti took up residence in Mexico City at the same time that Diego Rivera was called back to the country by Vasconcelos. She documented the murals with her camera and even is featured in some.24 Argenteri lays out a bit of beefy context:

The Mexican Revolution showed artists that a new approach to creation was not only possible but necessary. In a way, it was the recurrent theme of the ancient Mexican culture: humanity has to destroy itself in order to be reborn. Instead of the exotic or the primitive feeding into European art, the reverse would happen: the training artists had received in European art would feed into the native Mexican tradition. In so doing, the artists were completing a cycle: they used native techniques and forms to enhance their own creative powers in order to explain the meaning of the revolution to the people who started it. The use of popular forms was encouraged both to ease communication and to construct a mythic past linked to the present.25

Modotti was one individual in two broader movements: the flocking to Mexico, which drew in nationals and foreigners alike, and the politicization of art and culture. These movements grew out of the revolution, which was suffused with populist ideals. It produced a Mexican-born concept of what was being felt around the world by liberals, socialists, and communists.

~

Edward Weston was patently resistant to political involvement. His life with Tina Modotti, though, swirled through the same social whirlpool that was fomenting the cultural and political movement at the time. His journals from this period, referred to as Daybooks, are filled with accounts of visits with Diego Rivera and his then-wife, Guadalupe, as well as late-night drop-ins from both ex-pat and Mexican artists and liberal thinkers. There are descriptions of portrait sittings of friends, of dinner parties featuring pasteles served alongside Modotti’s spaghetti with butter, as well as Communist meetings in which Weston always gives a hard pass. His Daybooks describe the bullfights, the cloud conditions, the difficulties of lugging his 8 x 10 camera equipment through sand dunes and mountain passes, and his burgeoning Modernist aesthetic. He writes of their furniture, of letters from Margrethe Mather and from his wife Flora Chandler, of the reception of his exhibitions, of his sons, of ugly wallpaper.26 He skirts around the edges of his relationship with Modotti, which I can only assume was such a monumental part of his life at the time that it seemed too obvious to devote too much time to in his journals.

Weston and Modotti had arranged a very clear professional agreement surrounding the operation of his portrait studio in Mexico City. In a February 1924 letter to his family, Weston spelled out the terms of the exchange. Letizia Argenteri puts it thus: “He was going to teach her photography, taking her as his apprentice,” and generally, this is the party line. I take the term “apprentice,” though, as a generous understanding of the exchange. The grocery list of Modotti’s responsibilities and contributions goes on:

She was going to be his agent, his business assistant, which meant several things; she would act as a cushion against cultural shock; as a link to a different social code; as his darkroom assistant; and as an interpreter (her Italian helped her when speaking with Mexicans, even though her Spanish was not yet fluent.) In short, she was going to run their household and make all the necessary professional contacts.27

Modotti and Weston’s living expenses – food, etc., photography supplies, and rent for the living space they shared with his son and a servant – rested mainly on the income from the little portrait studio. Certainly Weston taught her the creative and commercial skills of photography on her request; however, the assumed and unpaid labor that fell upon her in her wife-like position far complicates the common understanding of an apprenticeship. Outside of the realm of the portrait studio, Modotti was responsible for all of the typical domestic labor delegated to the woman of the house. Specifically, she was responsible for his son, the overseeing of their servant, and hosting their social events.

In relation to the business, even, there was an extreme imbalance of work and compensation predicated on the imbalance of their genders. Her work as his darkroom assistant would clearly have been a fair enough trade for his instruction; however, this was not the extent of the agreement. As stated above, Modotti performed duties as his “business assistant,” the operational responsibilities of running the portrait studio that would have alone qualified a man as an equal business partner. Beyond that, the reputation of the studio and its stream of income (new clients coming in, old clients returning) depended upon her work as his agent. The business remained afloat because of Weston’s growing notoriety and position in the social and cultural landscapes of the city – all of which required networking, press, and contacts, crucial work which fell on Modotti’s shoulders.28 Add on her linchpin role as his translator, and it is clear that Modotti was exploited in the professional realm. She was appreciated, but not compensated or credited. Her value remained in the sentimental realm.

Argenteri outlines Modotti’s value as an emotional support to Weston in the list of her professional duties, (the comfort she offered him in a foreign country was instrumental to pulling off the whole thing) yet I am hesitant to count that contribution in economic terms. Could not the same be said of him? And, I want to push against conceiving of closeness and intimacy (for it is evident that Modotti and Weston shared both) in quid pro quo terms. However, I do see their romantic relationship as augmenting the inequity of their professional agreement.

I’ve already touched upon the ways in which her labor was undervalued, in her work directly and indirectly related to the portrait studio, but her economic dependence on and the fragility of her position as his lover beg to be underscored. Her labor went to the portrait studio, which supplied the income that she and Weston relied on, and yet she had no legal claim to the business entity or to the funds it generated. For the few years they were together, Modotti’s livelihood was dependent on her romantic relationship with Weston. If his attention had wandered to another, as it had done before from Margrethe Mather to her, or if the very quality he valued in her and that drove their business (her desirability and charm) had inspired too much jealousy in him, than she would have been shit out of luck. She would have had no legal recourse to claim partial ownership. As the woman in this hetero-pairing, the full weight of the dissolution would have fallen on her. There is convincing evidence that Modotti was aware of her precarious position (as Weston’s partner, sure, but as a woman at large, moreover) and that this was the reason she asked for Weston’s instruction, though it is hard to say for sure without being able to ask her about her motivations directly. I wonder how this imbalance in economic security informed their interpersonal interactions; I wonder how the major modes of female marginality played out in the minor case between these two.

~

I did not find any expressions of frustration or feelings of violation by Modotti, though perhaps a finer combing could bring some up. The record shows that they were in love. In one letter she writes to him, “Edward: with tenderness I repeat your name over and over . . . ”29 In 1924, she even handwrites her own will and testament in which she bequeaths all of her possessions to him.30 And, he writes in his Daybooks of their relationship, “certain it is I blush with shame, growing unutterably miserable when I remember or reread opinions I have indulged in regarding Tina; especially does this happen after such a night as came to us last Saturday. The pendulum must swing back and forth, the mercury rise and fall when two people live in too close contact, - but the retrospect of years will return to me overwhelmingly only the fineness of our association. I am sure of this.”31 So, they were in love, and it seems to have been a passionate love.

But it doesn’t quite fit to ask the question, “Were things between them unequal?” and to accept the answer, “They were in love.” Love is not a lead ball plopped down on one side of the scale or the other when weighing the question of inequity and injustice. Modotti’s articulation of her own economic exploitation or other subordination is not the question at hand. Besides, historical subjects aren’t fully trustworthy sources – or, at least, their scope cannot be assumed to be comprehensive. Lauren Berlant explains the uniquely contradictory nature of female marginality in her 1988 essay “The Female Complaint”: “Unlike other victims of generic social discrimination, women are expected to live with and to desire the parties who have traditionally and institutionally denied them legitimacy and autonomy.”32 Desire and love are built into the dynamics of phallocentric social domination. So, whether she loved him or not, (it’s clear that she did) whether she felt he treated her well, (this seems to be the case more or less) whether she felt respected or coerced, (I cannot say) the web of gendered power structured the world in which she lived.

~

Weston is remarkably sensitive to her predicament, even in his complicity.

March 1924: There is a certain inevitable sadness in the life of a much-sought-for, beautiful woman, one like Tina especially, who, not caring sufficiently for associates among her own sex, craves comraderie and friendship from men as well as sex love.33

~

Modotti and Weston lived together in Mexico City between 1923 and 1926, when he alone returned to California.34 Over the course of those three years, I believe they did work together as creative partners after she transitioned from strictly his model and lover to a creatively independent photographer. Argenteri, here! Look! This is what I am drawn to about Modotti: she carved a space for herself out of an exploitative frame. She leveraged her feminine currency to gain the skills and respect that afforded her some agency. And it only took a few years for her to shake him. But it still remains that the nature of their relationship was unequal, and history has proven that it has overwhelmingly benefited him: it is Weston who sits in the pantheon of photography. The authorship of some of the work that got him there, though, has been contested, especially the photos published in Anita Brenner’s book Idols Behind Altars.35 How many were hers? How many of his were developed and printed by her? So without a bit of effort on the reader’s part, Tina Modotti’s legacy remains as Weston’s lover and favorite model alone, and it lives on as such as her nameless nipples continue to pop up in generations of Intros to Art History.

~

This is the legacy that I take issue with, the narrative of a lover and muse. In the artwork, Tina Modotti is acted upon by the misogynistic power dynamics built into the photographic tradition. In fact, we can locate in the relationship between Modotti and Weston itself a building block to these exploitative, gendered structures. I am concerned with the power dynamics as they ruled the staging of the photographs inter-relationally and in the formal content of the images themselves. The historical conditions at the scene of the photographing are on trial as much as the photograph.

~

January, 1924: She leaned against a whitewashed wall – lips quivering – nostrils dilating - eyes heavy with the gloom of unspent rain clouds – I drew close to her – whispered something and kissed her – a tear rolled down her cheek – and then I captured forever the moment - let me see f.8 – 1/10 sec. K1 filter – panchromatic film – how brutally mechanical and calculated it sounds – yet how really spontaneous and genuine – for I have so overcome the mechanics of my camera that it functions responsive to my desires – my shutter coordinating with my brain is released in a way — as natural as I might move my arm – I am beginning to approach actual attainment in photography – that in my ego of two or three years ago I thought to have already reached – it will be necessary for me to destroy, to unlearn, and then rebuild upon the mistaken presumptuousness of my past – the moment of our mutual emotion was recorded on the silver — the release of those emotions followed - we passed from the glare of the sun on white walls into Tina’s darkened room – her olive skin and sombre nipples were revealed beneath a black mantilla – I drew the lace aside.36

~

The above excerpt from Edward Weston’s Daybooks describes the making of his photograph Tina with Tear. A deep analysis of Weston’s internal narrative of the creation of this image is instrumental to understanding the phallocentricity of the art photography tradition.

Edward Weston was developing Modernist aesthetics at a time when photography was transitioning from an unknown entity, first valued as a scientific spectacle then awkwardly applied to painting’s rules of two-dimensional representation, to a solidifying self-contained artistic medium. Our current understanding of the contours of the medium, inherited from the dominant narrative of the art history of photography, can largely be attributed to Weston’s drive towards formalism. “Form follows function,” and the function of photography is to witness – this is Weston’s legacy.37 The previously predominant concept of the medium, however, was of an art form that was as equally manipulated as painting or drawing. Before Weston, photographs were massively re-touched with brushwork. In fact, in its artistic infancy, photography was thought of as the product of “a pencil of nature,” the title of the first published photography book by William Henry Fox Talbot.38 Light itself was understood to be this pencil, drawing pleasing images. This comparison of the medium to drawing establishes the large degree of intervention understood to be a natural characteristic of photography. With Weston’s help, the concept of photography as a manipulated representation (with the focus on the “pencil”) moved to the idea of it as a physical re-presentation (with the focus on the “light”).

In the wake of Weston’s work, the Peircian system of symbols has been applied to photography. The founder of semiotics Charles Sanders Peirce described three kinds of signs: the symbol, the icon, and the index.39 The symbol has no formal relation as a signifier to what is signified, it is completely abstract and its attachment to its meaning is arbitrary, like the written word; the icon shares a likeness with what it signifies though there is no causal relationship; and the index both represents its meaning and shares a real, direct relationship to it.40 The best example of an index is a fossil or a footprint – the signified created the signifier. Photography is an indexical medium since the image is created by light reflected from the subject and recorded onto light-sensitive media (silver, celluloid, digital media card, etc.)

Weston helped to raise a cult of the index, which lauded photography’s indexical nature to the point of confusing its illusion of realism with realism itself. In his notes, Weston wrote, “Photography is a most intellectual pursuit. In painting or sculpture or what not, the sensitive human hand aids the brain in affirming beauty. The camera has no such assistance.”41 This notion over-emphasizes the physical connection a photographic image has to its referent and de-emphasizes to a dangerous degree the influence of the photographer’s subjectivity.

The cult of the index comes out of photography’s birth as a scientific achievement and from the historically unique question its introduction posed to artists: what distinguishes this form of two-dimensional representation from that form of two-dimensional representation, i.e. painting. The generosity of photography makes it seem unbiased. Once details were discovered in photographs that had gone unnoticed at the time of the photographing, it was easy to extrapolate photography’s function as evidence, as archive. There is already an authority in visual information, seated in a basic human reflex to overly trust our eyes. Additionally, the role of the camera was elevated from complex tool to author at a time when culturally we built up the infallibility of mechanics and automation as a comfort against human error.42 In Weston’s note, you can see the apotheosis of the machine as his sentence, “the camera has no such assistance,” is structured with “the camera” in the subject position. The tool has usurped the agency of a person. (Just there, again, too)

However, beyond the many opportunities within the production of a photograph for human intervention (staging, lens distortion, composite negatives or digital images, and retouching), there is the matter of the limit of scope. This is key. When the camera is understood as a witness, the meaning of the photo functions synecdochically. Only that which is captured in the finite frame of the photo stands in for broader reality, for Truth. This is the danger, as photographs present the slice of information they hold as exhaustive and unquestionable. It’s not that the viewer automatically drops all knowledge of the world outside of the frame, rather the systems operating within the photo remain uncontested and, beyond that, are applied to the world without. Photography does not present meaning; it produces it. One can easily understand the artifice of photos on a superficial level when any one of the many readily available examples is taken into consideration – easiest of which to access is the classic use of Hershey’s chocolate syrup as a stand-in for blood in the shower scene of Psycho. (Another favorite photographer of mine, Les Krims, carries on the trope in his portfolio The Incredible Case of the Stack O’Wheat Murders) Weston unwittingly illuminated the metamorphic power of photography when he wrote in 1932, “through photography one presents the significance of facts, so they are transformed from things seen to things known.”43 Weston wrote this in support of his objective photography line of thought: seeing is a function of people, who are susceptible to error and deceit; photography, on the other hand, has the power to corroborate a person’s shaky testimony and make it known. Weston has muddled meaning here, though – his note highlights not the objectivity of photography but instead its malleability.

Since we are robbed of other sensory information, what is sweet becomes sinister in the case of the Hershey’s syrup. This is precisely because photographic signification functions metonymically and absolutely. Photos are conjugated in the tense of “that which has been,” remember? – Not “that which could be.”44 It’s not just a sugary taste or the smell of cocoa that can be hidden in a photo, though, the erasure of unrecorded information is much more insidious than that – photos don’t pick up on systems of exclusion and oppression.

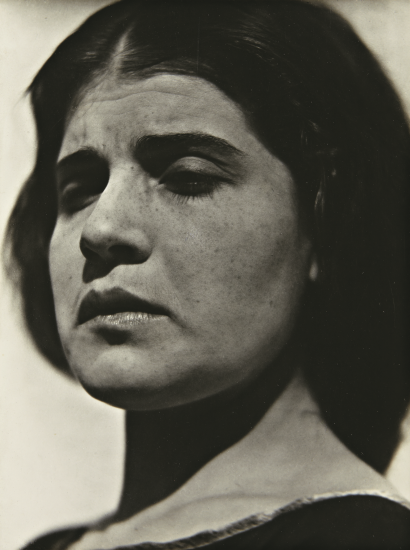

Tina With Tear, Edward Weston 1924

~

“She leaned against a whitewashed wall – lips quivering - nostrils dilating - eyes heavy with the gloom of unspent rain clouds - I drew close to her - whispered something and kissed her - a tear rolled down her cheek - and then I captured forever the moment - let me see f.8 - 1/10 sec. K1 filter - panchromatic film - how brutally mechanical and calculated it sounds - yet how really spontaneous and genuine - for I have so overcome the mechanics of my camera that it functions responsive to my desires - my shutter coordinating with my brain is released in a way — as natural as . . .”

You’re kidding yourself if you tell me you weren’t surprised by Weston’s choice of the next words, “I might move my arm.” Weston is painting a picture of male desire here. He builds up sexual tension by describing Modotti’s physical features, features typical of arousal. And then he kisses her! Weston does an interesting thing in this passage: he both speaks of his camera technically and as the locus of his own sexual desire. Here, his desire for Modotti sparks an automatic course of action that results in the release of his camera’s shutter. If you ask me, the more appropriate bodily metaphor would be the release of his ejaculate. Weston could move his arm whenever he wants for whatever purpose; there’s a degree of control over that kind of bodily movement that does not accurately mirror the release of a shutter. Though he does not consciously have to command his arm to move, he chooses when and how to move the arm – and he can stop mid-way through the action. Ejaculation, on the other hand, is truly an automatic reflex that can’t be interrupted once it’s begun. And, it’s set off by desire, too.

By speaking of his camera in terms of both mechanics and male sexuality, Edward Weston equates the two. He sets up male sexual desire on par with the laws of physics, which rule the operation of machinery. Male desire is supra-human, male desire is all-reaching, male desire is logical. It is as omnipresent and as omnipotent as gravity. All bodies in motion, or something or other. Weston’s narrative of the Tina With Tear scene postures male desire as the natural law of the universe.

This is a perfect lead-in to Laura Mulvey’s idea of the male gaze, which I want to apply as a mode of formal analysis to the resulting imagery, but put a pin in it for a moment, if you will. I want to first highlight the other ways in which Weston reveals his male-dominant worldview in this passage before moving on to the visual text.

Secondary to his allusions to sexuality is his use of the language of possession. This, in fact, is built into the language of photography (not a coincidence, I would argue). The first part of the excerpt is written poetically with a sprinkle of metaphor and a slow, even cadence. The reader is snapped out of it, though, with the next sentence, “and then I captured forever the moment.” The ease – maybe, the seduction – of the first part is broken by that word, “capture,” which not only establishes a relationship of ownership but also does so in a manner of violence. “Capture” evokes hunting, predator and prey, or else, at the very least, the possession of something that resists. The fact that the something sweet he whispered to her is unnamed in the Daybooks makes clear that it was only bait for a display of emotion. Weston’s intention may not have been quite so explicit or manipulative, but the falling away of the particular words or sentiments makes clear the sweet thing’s lasting function is only as bait. He pays great attention to record in specific detail his camera settings, yet whatever feeling passed from him to her before the tear is unimportant. Weston has “captured forever” the moment of intimacy and desire in a photo, and now the photo is a cage of sorts. There’s no way around it. Try to find a less offensive or severe word. He captured the moment: he took a photo: he photographed her. To photograph is a verb of possession. Our language for the medium is built up around a forceful transference of ownership. A camera is a gun, and it holds its subject hostage if it doesn’t take a life. Weston continues to deploy possessive, dominant language in the excerpt: “I have so overcome the mechanics of my camera,” and “I am beginning to approach actual attainment in photography.” This is the male ego running free. He even admits to past overestimation, but he really thinks he’s got it this time around. Phallocentrism reveals itself as control; Weston’s desire controls the camera, Weston’s got a handle on – can perfectly articulate and therefore calculate – the logic of photography.

The last layer within the excerpt I’d like to touch upon is Weston’s usage of light/dark imagery, not to be overly theatrical. The usage of this extreme dichotomous metaphor is relevant because light is the central material of the photographer’s craft. In the scene, all usage of darkness is associated with Modotti: “Eyes heavy with the gloom of unspent rain clouds.” “The moment of our mutual emotion was recorded on the silver – the release of those emotions followed.” Weston stages the photographing scene as foreplay to a moment of intimate, emotionally connected sex. When the two move through this course of action, pay attention to the light/dark imagery: “We passed from the glare of the sun on white walls into Tina’s darkened room – her olive skin and sombre nipples were revealed beneath a black mantilla – I drew the lace aside.” Light is the condition necessary for a photograph. To shine a light on something is to prepare it to be photographed and enable it to be possessed. Modotti and Weston pass from the sundrenched scene of the photograph, which is driven by his actions, to her darkened room, a place where the camera’s testimonial is eluded. If the significance of facts must be seen to be known then darkness represents mystery (I don’t need to tell you that). Every reference to darkness is connected to Modotti: her room, her skin a darker shade of olive – even her nipples are described in a bizarrely dark tone. (Who has such ominous nipples?) When Weston draws the lace of her black mantilla aside, he is allowing light to enter and for Modotti to enter into his control.

~

I will now use Laura Mulvey’s theory of the male gaze as described in her groundbreaking 1975 essay Visual Pleasure and Narrative Film in my formal analysis of Weston’s imagery.45 Though there has been much work done in gender studies and cultural criticism since, Mulvey’s still packs a punch and provides a necessary foundation for understanding how visual culture constitutes the realm in which female marginality is both described and applied.

Mulvey uses psychoanalysis as “a political weapon, demonstrating the way the unconscious of patriarchal society has structured film form” in her paper. She focuses the scope of this weapon onto popular, narrative cinema; however, the tools she uncovers in this analysis fit well with photography.. Linda Williams better outlines how to stretch Mulvey’s vision backwards onto cinema’s predecessor, still photography. Eadweard Muybridge is the link. He is the historical signpost pointing in two directions, one to the past and still imagery and the other to the future and moving images. He is also the rumored start of the idea of a camera as a gun. And, not insignificantly, a fetishized piece of fabric (whose function is much like Modotti’s black mantilla) plays a central role in William’s argument.46

First, Mulvey presents her tools. Take her employment of Freudian psychoanalysis with a grain of salt, please. At the very least, Freud certainly provided a useful vocabulary for discussing the invisible, undercurrent nature of societal structures. Freud isolated the pleasure of looking itself, called scopophilia, in his Three Essays on the Theory of Sexuality as “one of the component instincts of sexuality which exists as drives quite independently of erotogenic zones.”47 This is to say that scopophilia is a kind of pleasure that contributes to sexual excitement but is not directly connected to physical stimulation. It is, however, a kind of sexual stimulation, derived from the “taking [of] other people as objects, subjecting them to a controlling and curious gaze.”48

The worn-out (but oh-so hard-working) phrase “male gaze” is coined here to describe the essential relationship of woman’s role as image to man’s role as “Bearer of the Look.” Mulvey writes, “In a world ordered by sexual imbalance, pleasure in looking has been split between active/male and passive/female. The determining male gaze projects its phantasy on to the female figure which is styled accordingly.”49 Narrative cinema is Mulvey’s concern; however, cultural production is written for a male audience by default, with just the exception of women’s genres, since it is understood that only men inhabit the public sphere. I am borrowing Berlant’s definition of the public sphere, rather than the typical purely political space the term usually refers to in Enlightenment-era political theory. Berlant explains, “Instead, the public sphere is a place designated by a group or a subject’s perception of where socially, politically, and culturally normative value is determined and regulated. Such a definition accommodates the shifting operations and perceptions of power within a culture, allowing for more consideration of the confusions of identity within subcultures of race, gender, or nationality, where complex identities are formed in the light (and in the shadows) of an apparently dominant and exclusionary social nexus.”50 (Whew!)

Mulvey then dives into her formal analysis. Mulvey outlines cinema’s history of seamlessly entwining spectacle and narrative. Woman’s typical place in film has been twofold; she functions as an erotic object for the characters within the story and as an erotic object for the members of the audience, “with a shifting tension between the looks on either side of the screen.”51 Think of the kinds of moments when the camera pans from the protagonist down his line of sight to the woman he is watching. Think of Jessie, naked and strumming her guitar on stage, in Forrest Gump. Mulvey:

“For a moment the sexual impact of the performing woman takes the film into a no man’s land outside its own time and space. Thus Marilyn Monroe’s first appearance in The River of No Return and Lauren Bacall’s songs in To Have or Have Not. Similarly, conventional close-ups of legs (Dietrich, for instance) or a face (Garbo) integrate into the narrative a different mode of eroticism. One part of a fragmented body destroys the Renaissance space, the illusion of depth demanded by the narrative, it gives flatness, the quality of a cutout or icon rather than verisimilitude to the screen.”52

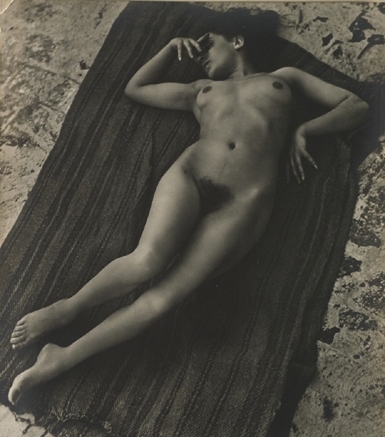

Non-humanist perspectives break the diegesis of narrative film as much as they break the diegesis of the illusion of realism within photography. Renaissance space is exactly broken in this way in Weston’s 1924 photo, Tina, On the Azotea. In his Daybooks, Weston describes the public’s general poor reception of the break in humanist perspective, though he receives praise from an artist he admired. Not only does the unsettling perspective operate in exactly the way Mulvey describes but it also reveals Modotti’s full nudity.

Tina, On the Azotea, Edward Weston, 1924

Close-ups, as well, take the image out of the context of a woman as a subject and push the imagery into an erotic spectacle, one that robs her of her personhood. Mulvey, again: “Woman then stands in patriarchal culture as signifier for the male other, bound by a symbolic order in which man can live out his phantasies and obsessions through linguistic command by imposing them on the silent image of woman still tied to her place as bearer of meaning, not maker of meaning.”53

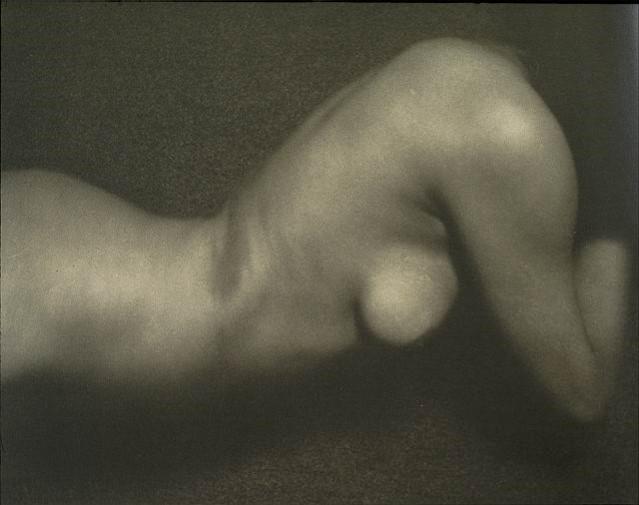

Nude (Tina Modotti), Edward Weston 1921

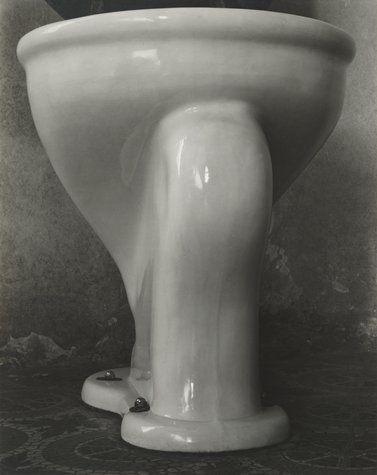

One of Weston’s many nudes of Modotti illustrates the point. She’s headless and legless and handless. Mulvey goes on to explain, “Fetishistic scopophilia can exist outside linear time as the erotic instinct is focused on the look alone.”54 This, too, contributes to the imbalance of power, for the subject is frozen in time but the viewer can indulge in looking unmitigated. The viewer says, “I can put you in my pocket, and take you out whenever I please.” Weston’s obsession with form extended past the female body. He treats his lover’s body with the same care as he does their toilet, or later a bell pepper.

Excusado, Edward Weston, 1925

Pepper, Edward Weston, 1930

Weston, again, sets up an equation of meaning. Modotti’s curves are bearers of Beauty as much as the curves of any old thing. Modotti’s being is circumscribed by the function of symbol applied to her.

Tina Modotti goes down in history as a blank canvas onto which men projected their fantasies. Her subjecthood is muffled in the photos as they were in in life. It seems that every man she knew fell in love with her. “Pablo Neruda wrote that he had to make an effort, as if he were holding a handful of fog, to remember Tina since she was a fragile, almost invisible creature, and yet her pale oval face with her large, velvet eyes were printed on his mind.”55 She was an icon, in the Peircian sense, dominated by the meaning assigned to her in Weston’s photographs. Beyond that, if she’s gained any notoriety, it is merely as an icon as well, in the pop culture sense. Both roles fetishize her – I think I was about to fetishize her as well.

~

I went down this line (rabbit hole) of inquiry to do an ethical arithmetic on Modotti. I knew she was subjected to Weston’s objectification, but I wondered if she had been doomed to perpetrate the trauma doled out to her. My starting question was, “what is there to make of a European who photographed indigenous workers with the intention of using the portraits as symbols to rally support for an international, political cause?” Did Modotti see her subjects as Noble Savages? I had thought that she slipped in and out of the roles of exploiter and exploited when she stood on both sides of the camera lens. But no, I am satisfied that she did not exploit her subjects. She was not alone in the trend. She was not the first, nor the most prolific. She had a sensitive eye, and she understood the plasticity of photography. She wrote in a letter to Weston the phrase, “a camera which could produce magic: that is, give a shape to creativity.”56 In 1929, Modotti published a small article in English and in Spanish, in the journal Mexican Folkways as her treatise On Photography. She wrote,

“Photography, precisely because it can only be produced in the present and because it is based on what exists objectively before the camera, takes its place as the most satisfactory medium for registering objective life in all its aspects. If to this is added sensibility and understanding and, above all, a clear orientation as to the place it should have in the field of historical development, I believe that the result is something worthy of a place in social production; to which we should all contribute.”57

Worker’s Parade, Tina Modotti, 1926

~

A bona fide Modernist, Modotti agrees with Moyra Daveys and me,

“To know whether photography is or is not an art matters little. What is important is to distinguish between good and bad photography. By good photography is meant that photography which accepts all the limitations inherent in photographic technique and takes advantage of the possibilities and characteristics the medium offers. By bad photography is meant that which is done, one may say, with a kind of inferiority complex, with no appreciation of what photography itself offers; but on the contrary, recurring to all sorts of imitations.”58

~

Photographs not explicitly about photography cloak the erasure inherent in their form. Photographs are unstable signifiers, unfixed.

~

One last little trickle of thoughts: here’s Argenteri on Modotti’s role as Edward Weston’s translator – what a treat!

“In Mexico Tina became his spokesperson but she also often translated his statements loosely or distorted reality a little in order to present Weston as a public figure who cared about Justice. In September 1923, for example, during an interview with a Mexican journalist, Modotti made Weston appear far more radical than he actually was, saying that he had left the United States because he found it impossible for an artist to cope with the restrictive laws, Prohibition, and the rising Ku Klux Klan.”59

1 Davey, Moyra, and Helen Anne. Molesworth. Long Life Cool White: Photographs & Essays. Cambridge, MA: Harvard U Art Museums, 2008. Print. p79

2 Ibid. p83

3 Ibid, p89

4 Argenteri, Letizia. Tina Modotti: Between Art and Revolution. New Haven: Yale UP, 2003. Print. pxv

5 Ibid

6 Lowe, Sarah M. Tina Modotti: Photographs. New York, NY: H.N. Abrams in Association with the Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1998. Print.

Hooks, Margaret. Tina Modotti, Photographer and Revolutionary. London: Pandora, 1993. Print.

7 Argenteri, Letizia. Tina Modotti: Between Art and Revolution. New Haven: Yale UP, 2003. Print. pxiv

8 "Biography." Tina Modotti Web Museum. N.p., n.d. Web. 9 Argenteri, Letizia. Tina Modotti: Between Art and Revolution. New Haven: Yale UP, 2003. Print. p32

10 Argenteri, Letizia. “Udine.” Tina Modotti: Between Art and Revolution. New Haven: Yale UP, 2003. 1-11. Print.

11 Ibid, p29-30

12 Ibid, pxvi-xvii

16 Ibid, p46

17 Ibid, p47, p55, p62

18, 19 "The Mexican Revolution: November 20th, 1910 | EDSITEment." The Mexican Revolution: November 20th, 1910 | EDSITEment. National Endowment for the Humanities, n.d. Web. 15 July 2015. 20 Argenteri, Letizia. Tina Modotti: Between Art and Revolution. New Haven: Yale UP, 2003. Print. p46

21 "The Mexican Revolution: November 20th, 1910 | EDSITEment." The Mexican Revolution: November 20th, 1910 | EDSITEment. National Endowment for the Humanities, n.d. Web. 15 July 2015. 22, 23, 24, 25 Argenteri, Letizia. Tina Modotti: Between Art and Revolution. New Haven: Yale UP, 2003. Print. p48-50

26 Weston, Edward, and Nancy Wynne. Newhall. Daybooks of Edward Weston: Vol. 1 & 2 Mexico/California. Vol. 1. S.l.: Aperture Book, 1973. Print.

27 Argenteri, Letizia. Tina Modotti: Between Art and Revolution. New Haven: Yale UP, 2003. Print. p61

28 Ibid, p69

29 Ibid, p59

30 Ibid, plate

31 Weston, Edward, and Nancy Wynne. Newhall. Daybooks of Edward Weston: Vol. 1 & 2 Mexico/California. Vol. 1. S.l.: Aperture Book, 1973. Print.

32 Berlant, Lauren. "The Female Complaint." Social Text 19/20 (1988): 237-57. JSTOR [JSTOR]. Web. p238

33 Argenteri, Letizia. Tina Modotti: Between Art and Revolution. New Haven: Yale UP, 2003. Print. p32

34 "Biography." Edward Weston. N.p., n.d. Web. 15 July 2015. 35 Argenteri, Letizia. Tina Modotti: Between Art and Revolution. New Haven: Yale UP, 2003. Print. p80

36 Weston, Edward, and Nancy Wynne. Newhall. Daybooks of Edward Weston: Vol. 1 & 2 Mexico/California. Vol. 1. S.l.: Aperture Book, 1973. Print.

37 "Biography." Edward Weston. N.p., n.d. Web. 15 July 2015. 38 Fox Talbot, William Henry. "The Pencil of Nature." The Pencil of Nature. N.p., n.d. Web. 15 July 2015. 39, 40 "Semiotic Elements and Classes of Signs." Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation, n.d. Web. 15 July 2015. 41 Argenteri, Letizia. Tina Modotti: Between Art and Revolution. New Haven: Yale UP, 2003. Print. p74

42 Drawing from Benjamin, Walter. "The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction." Stardom and Celebrity: A Reader (2007): 25-33. Web.

43 Argenteri, Letizia. Tina Modotti: Between Art and Revolution. New Haven: Yale UP, 2003. Print. p74

44 Drawing from Barthes, Roland. Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography. New York: Hill and Wang, 1981. Print.

45 Mulvey, L. "Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema." Screen 16.3 (1975): 6-18. Web.

46 Williams, Linda. "Film Bodies: Gender, Genre, and Excess." Film Quarterly44.4 (1991): 2-13. Web.

47, 48, 49 Mulvey, L. "Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema." Screen 16.3 (1975): 6-18. Web.

50 Berlant, Lauren. "The Female Complaint." Social Text 19/20 (1988): 237-57. JSTOR [JSTOR]. Web. p240

51, 52, 53, 54 Mulvey, L. "Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema." Screen 16.3 (1975): 6-18. Web.

55 Argenteri, Letizia. Tina Modotti: Between Art and Revolution. New Haven: Yale UP, 2003. Print. p70

56 Argenteri, Letizia. Tina Modotti: Between Art and Revolution. New Haven: Yale UP, 2003. Print. p44

57, 58 Modotti, Tina. "On Photography." Mexican Folkways Oct-Dec 5.4 (1929): 196-98. Print.

59 Argenteri, Letizia. Tina Modotti: Between Art and Revolution. New Haven: Yale UP, 2003. Print. p62