Chloé Wilcox

Body Language

ISSUE 38 | SCRIPTIO DEFECTIVA | MAR 2014

Truly, the human being knows his language even less than he knows his body: the sentence may be compared to a body, which invites us to disarticulate it, in order that its true contents may be recomposed through an endless series of anagrams. If one examines it closely, the anagram is born from a violent and paradoxical conflict. It presupposes a maximal tension of imaginative will and at the same time, of the technical limitations of the means at hand—only the given letters may be used.

–Hans Bellmer, Postscript to Oracles and Spectacles by Unica Zurn

* * *

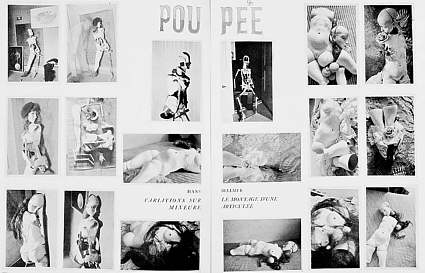

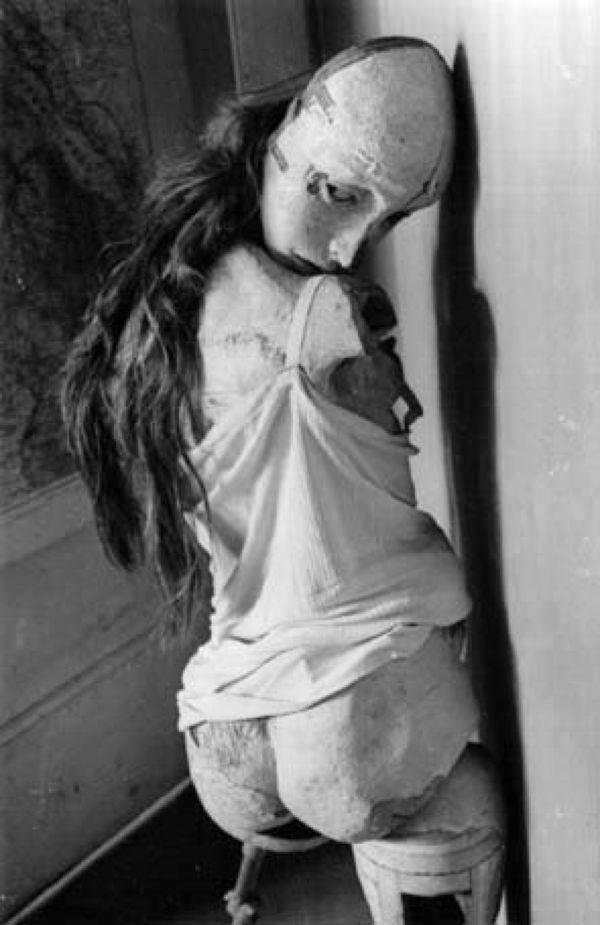

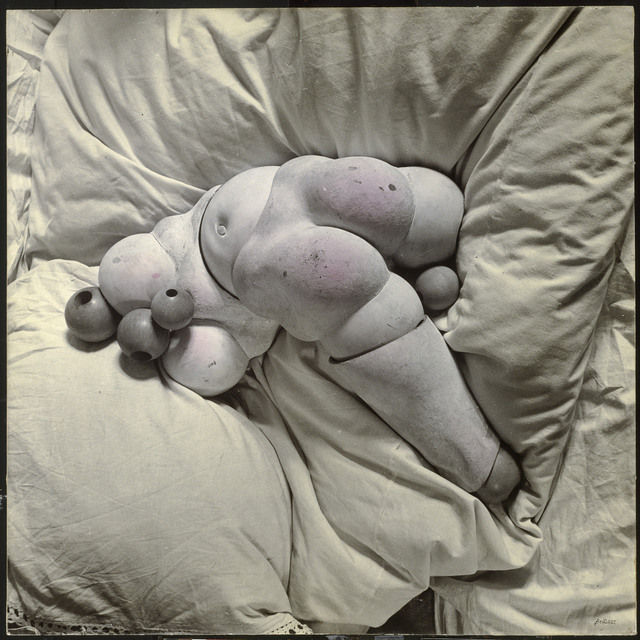

“Poupée: Variations sur le montage d’une mineure articulée” (Doll: Variations on the Assembly of a Jointed Girl), two-page spread, Minotaure (December 5, 1934)In 1933, Hans Bellmer, a German artist working in Berlin with a flair for Surrealism, began building and photographing a near life-size doll of a young girl. In the photographs, Bellmer presented this doll, designed to be dismantled and rebuilt, in varying states of undone, displaying her component parts parsed, the legs, arms, hands, torso, and head all neatly arranged on a palate, or else jumbled together with gauzes, artificial roses, and streams of lace. Here, her cadaverous mask looks coyly over her shoulder, her long hair tumbles down in waves and her scant slip rides up around her hips. There, she is decapitated, and her shorn head nestles into the hollow of her waist, crowning a mound of ball-shaped joints.

Hans Bellmer, Die Puppe (The Doll), 1934Bellmer compiled eighteen photographs of this first doll into a pamphlet he entitled Die Puppe (The Doll) and, unsatisfied with the results of this first experiment, swiftly began construction of a second doll in 1935. This subsequent doll was much more flexible than the first. Where the original doll’s torso was a rigid imitation of human anatomy, the new one’s middle was a large spherical joint, to which various appendages could be attached and around which they could be rotated.

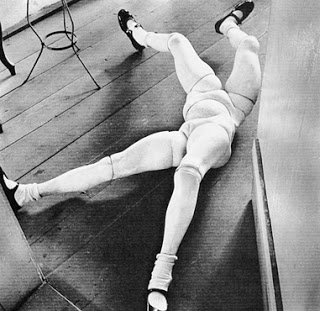

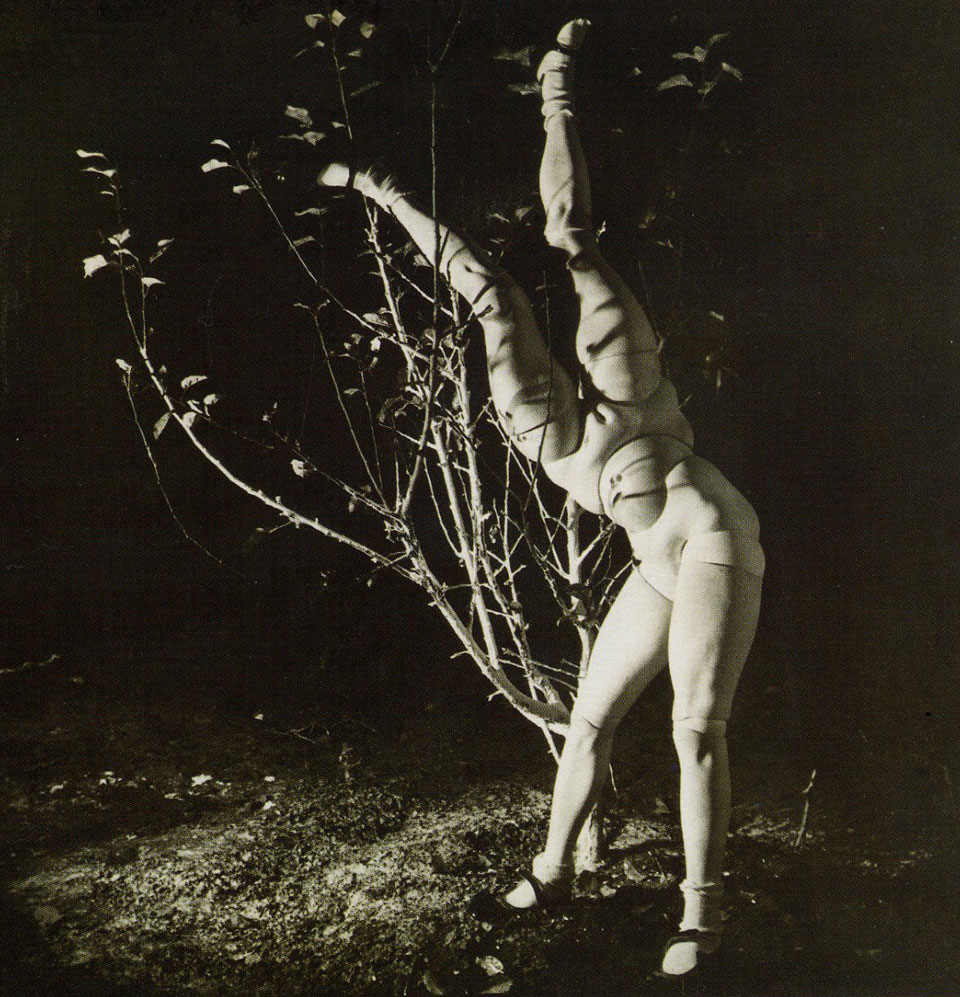

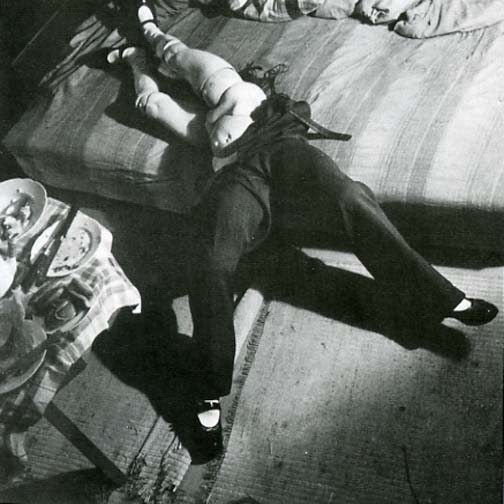

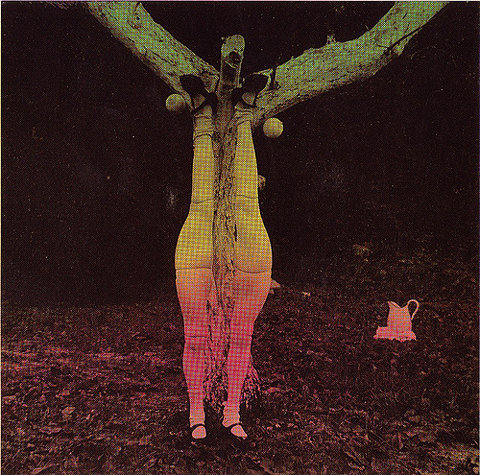

Bellmer catalogued this doll’s capacity for metamorphosis in over one hundred photographs, a small number of which he published in a book entitled Les Jeux de la Poupée (The Games of the Doll) with poems by Paul Eluard and his own text, A Brief Anatomy of the Physical Unconscious or The Anatomy of the Image, in which he described his project. (By this time, the Surrealists were clamoring to work with Bellmer.) These photographs present the second doll in strange and aberrant contortions in the familiar environs of the home or outdoors. Rarely furnishing the doll with her head, arms, or breasts, Bellmer instead duplicated her lower body on her upper body so that her form was at once severed and cloned. Despite her mutilated form, this doll appears keenly and uncannily animate in ways Bellmer’s first doll, whose photographs resemble still-lifes, did not. This figure is shown tensed: turned on her back, her legs writhe and flail; resting on a tree, her knee bends and her hip cocks coquettishly; supine on the bed, however, she is flaccid, the victim of some grave abuse.

* * *

Bellmer’s concept of the corporeal anagram hinged on a series of sensorial transpositions that he understood to originate from the primal and instinctive gesture of the reflex.

In this way the toothache is divided, graphically doubled, at the expense of the hand, whose ‘logical pathos’ becomes its visible expression. Should we then conclude that all the reflexes of the body, the face, a limb, the tongue, or a muscle—from the most violent to the least perceptible—may be explained in this way, as a tendency to divert and divide a pain and to counter a real centre of arousal with a virtual one? This much seems certain, and leads us to regard the desirable continuity of our expressive life as a sequence of liberating transferences that progress from a malady to its image. Expression together with its concomitant pleasure is a transposed pain, a liberation.

…She is filled with oneiric desires for vaguely formed promises or rewards of an emotional or sexual complexion. Since the fulfillment of her desires is denied her, she has a tendency to diminish the existence of her sex…nevertheless its content is still actively available and ready to assume a new meaning, to occupy a vacant place and cloak itself in permissible reality. …As soon as the intuitive position of the chin has indicated the analogy between sex organ and armpit, the two images become superimposed and intermingle.

For Bellmer, the reflex is the Ur-act of all expression. Significantly, it is not an act of communication with another entity, but a moment of interior somatic coping. The connection between smarting tooth and sympathetic hand does not end at imitation or representation. The moment the hand contracts into a painful ball, thus taking on the task of the tooth (to hurt), it forfeits its identity as hand and assumes that of tooth. Hand becomes tooth. So that when Bellmer dotingly remarks, “when your breasts seek to hide behind your fingers or your armpits—your blazing beautiful face,” he sees the hand and armpit as actually transforming into the breast and, by default, performing a self-amputation. It is this notion of sensorial transposition that Bellmer attempts to illustrate on the body of the doll, rearranging her limbs to account for the redirected flow of physical desire.

But, of course, the contortions presented in the photographs do not reflect the suppressed yearnings of the recumbent girl-child—arm vaulted across the table, fingertip daintily poised, armpit so wondrously replaced by her vagina—Bellmer describes lovingly (and lustily) in his writing. Instead, the doll’s body registers the spectrum of his denied desires. For Bellmer elaborates this idea of sensorial transfer out beyond the involuntary reflexive jerk to account not only for the internal migration of pleasure within a single entity but also for the “borderline case…when the entire individual perceives himself as a centre of arousal, and is countered by a virtuality that seems to exist outside of him, …the splitting of the personality into an ego that experiences arousal and an ego that produces arousal.” The corporeal subversion the doll figures is twofold. First, it is the physical literalization of Bellmer’s theory of the body as anagram, by which body parts are scrambled, replaced, and multiplied according to their sensorial ‘needs,’ and, second, it is the splitting and externalization of Bellmer’s consciousness, the migration of his form onto another. Bellmer takes advantage of the doll’s anagrammatic form to express his arousal; her limbs constitute his personal alphabet, with which he may spell out the story of his pleasure and his pain. It is this violent reconciliation between Bellmer’s “imaginative will” and the “technical limitations” of the doll’s form that the photographs document, archiving with each new print precisely the “liberating transferences” passing from Bellmer to the doll—“from a malady to its image.”

I

“Expression together with its concomitant pleasure is a transposed pain, a liberation,” says Bellmer. For Bellmer, there is no real distinction between pleasure and pain. Pleasure is simply pain expressed, pain liberated, pain witnessed. Just as it is at the “expense of the hand, whose ‘logical pathos’ becomes [the tooth’s] visible expression” that the ache is assuaged, so it is at the “expense” of the doll that Bellmer’s pain is diverted and diminished. Contingent on the doll’s pain, the pleasure Bellmer derives from this transfer is first and foremost sadistic. The doll’s suffering is Bellmer’s soothing distraction, and, contained in the static space of the photograph, she offers herself to his masterful gaze. In her decapitated form, she is literally deprived of a gaze, and in those few images when her jointed form is crowned with a head, she withdraws behind the distended orbs of her body or stares back with vacant eyes. Bellmer may look upon her contorted form with impunity and without obstruction. Variously splayed, strung up, or propped full-frontal, she is at his mercy.

The amputated and mangled forms Bellmer obsessively catalogues in hundreds of photographs announce the physically sadistic urge that underpins his desire. As the doll’s creator, Bellmer may literally fashion her exactly according to his will, doubling, dividing, adding to and subtracting from her body as he pleases. Every aberration born on the doll’s body registers a destructive act (and its preceding fantasy) performed by Bellmer himself. As much as it is Bellmer’s pleasure to witness pain, it is also his desire to actively illustrate it. He celebrates the violence of creation, referring to the “craftsman, turned criminal,” who “…just as the gardener forces the box tree to exist as a cone, sphere, or cube, so will [he] force his elementary certainties, the geometrical and algebraic habits of his thoughts upon the image of the woman.” He violently collapses linguistic praxis onto the palpable form of the body to create the best mode of expression. And it is, as the photographs demonstrate, an awfully grim affair. Bellmer seems to delight precisely in the fact that the human body is not anagrammatic at all, taking pleasure in his ability to forcibly impose this impossible quality on the doll’s passive body. The serial presentation of the photographs emphasizes the violence of Bellmer’s palliative endeavor. It is only through the shocking diversity of assemblages that the viewer can fully comprehend the extent of the disassemblage—the rending apart that the doll endures. For each new shape necessitates the physical dismantling of the preceding contortion. Every new form reminds us (and Bellmer) that we are, in fact, all too aware of the “technical limitations” of the human body, namely that it is not so easily “disarticulate[d]” as is a sentence, and that to treat it as if it were entails a terrifying and violent violation.

II

But as much as these photographs attest to Bellmer’s sadistic indulgence, they also register a masochistic desire; while the doll is at the mercy of her master, she is also a site of identification for him. If we interpret the photographs of the doll according to Bellmer’s theory, the doll’s contorted forms may be understood as the image of repressed physical desires that reside already within Bellmer, but which he cannot visibly express on his deplorably rigid form. Like the hand turned tooth, the doll, wrought in the image of his “malady,” is Bellmer, and Bellmer is the doll. Thus, when Bellmer plays the “craftsman turned criminal,” the sadistic deformations he inflicts upon the doll’s pliant form constitute, simultaneously, a diverted enactment of his masochistic desire to take on the impossible shapes. What his salacious gaze devours so exuberantly is the realized image of the torture he craves, but which his form is incapable of sustaining.

Hans Bellmer, La Poupée (The Doll), 1938

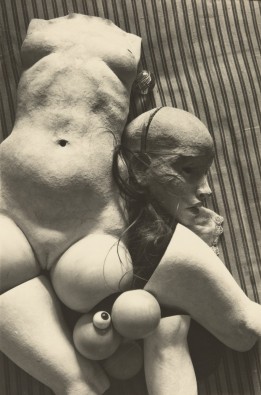

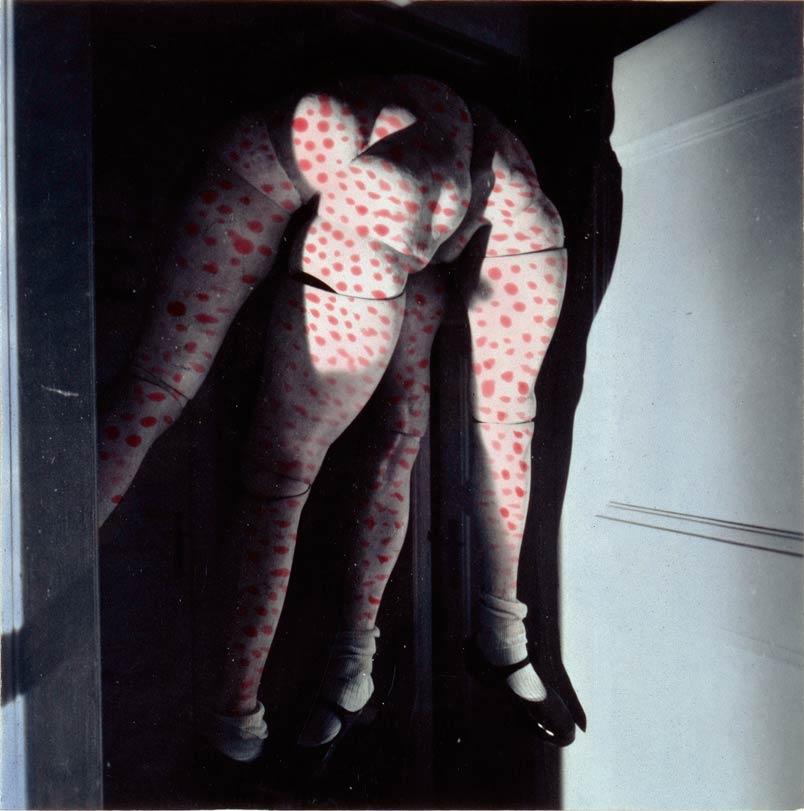

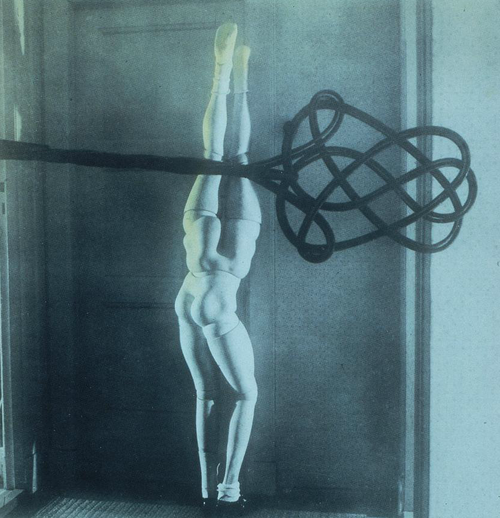

Plate XVI in Les Jeux de la Poupée, 1935Fittingly, the contortions captured in the photographs figure a quintessentially male affliction: castration. Although he did not feature her in all his photographs, Bellmer was especially fond of the headless, four-legged permutation of his doll, which we encounter tangled in a tree, suspended in a doorframe, or turned on her back, flailing like a deranged arachnid. This doll is a Medusan creature, a decapitated body of proliferating phallic forms, the terrifying epitome of castration. “To decapitate=to castrate,” Freud said, and this doll is adamantly both. The aberrantly multiplied limbs that sprout in place of her head, neck, and arms evoke the phallus, but these phallic limbs are debased and wounded, truncated and disjointed. The final photograph Bellmer published in Les Jeux de la Poupée presents the ultimate image of the castrated phallus. Here, the doll has been strung up in a doorway like meat on tenterhooks. Her four legs, covered in an array of leprous blemishes, hang impotently from the door, and one—the most prominently featured—bears a dark wound, a cavernous crack where the ball-joint of the torso separates from the appendage. This fissure evokes the castrative cut and, exposing the hollow interior of the phallic form, flagrantly reveals the phallus to be false. Furthermore, between the second set of phallic limbs, where the doll’s head should be, is also the calcified and inflated cavity of a second vulva, the fundamental sign for lack. The doll’s body is a site of replayed castration, and, like Medusa’s proliferating snakes, it finds potentially endless reproduction in each new photographic print. Submerging himself in hundreds of photographic images, Bellmer bathes in the stuff of his own thrilling nightmares.

Bellmer’s cure derives not so much from the simple displacement of his pain onto an external figure, but rather from its adamant confirmation in an extension of himself, from its externalization and its subsequent re-absorption into his body. The hand that convulses in response to the toothache relieves the tooth by creating greater pain, its secondary throb serving as a complement to the initial oral pang. The doll, as Bellmer wished her, is a “provocative object” whose form reveals to Bellmer the nature of his desire. He did not imagine the transference as a one-way displacement. To successfully release his frustrated desire—to transform this pain into pleasure, the transposition depended on a certain receptivity and reciprocity in nature, a kind of animistic imminence in the world. “One can envisage a kind of projection screen erected between the ego and the outside world, on to which the unconscious projects the image of its momentary source of arousal, but which only becomes visible to consciousness when the same image is simultaneously cast on to the screen from the other side and the two images are congruent.” The “virtual centre of arousal” must be found ready-made, a sacrificial offering from the order of things. The doll’s form anticipates Bellmer’s pain, matching him from the other side of the screen. It is in the photographs that the doll achieves this essential facet of “virtuality.” The moment the doll, contorted in the fashion of Bellmer’s fancy, is eternalized in the photographic act, she ceases to be an object made—a fleeting representation—and begins to exist outside Bellmer, slipping into reality as a thing in her own right. Bellmer may look upon these images and see his masochistic desire for violence and rupture mirrored back out at him, already materialized on the flesh and in the world. No longer a medium of expression, she is the “ego that produces arousal,” an object of desire.

III

“For a brief instant the individual and the non-individual become interchangeable and the terror of the ego’s mortal limitations in time and space is extinguished. …It is in such heightened moments of resolution that a thrill of fearless horror is transformed into an intensified feeling for life, into an illusion: the sense that one is participating, beyond the span between birth and death, in the existence of a tree, in the YOU, in the fate of inevitable chance, yet remains Self, as an echo—on the other side.”

—A Brief Anatomy of the Physical UnconsciousBellmer’s photographs of the doll catalogue both a sadistic impulse to violently master a passive object and a masochistic yearning to be the contorted object. These parallel currents of desire are seemingly contradictory, even irreconcilable. But it is precisely this concomitance of apparent opposites that most enthralled Bellmer. He believed the “real centre of arousal” and the desired, “virtual” one did not remain separate but instead comingled in a tense union wherein the divisions between the real and the imaginary, the licit and illicit, the subject and the object were blurred. This synthesis suggests a rupturing of the defined boundaries of the world, in which what acts and what is acted upon are inextricably linked. Bellmer’s professed desire to overcome “the ego’s mortal limitations in time and space” reframes the sadistic and masochistic impulses registered in the photographs of the doll’s body as identical urges to pass beyond the limits of self and other. For Bellmer’s sadistic distortion of the doll’s human form conforms her body to another order as much as it inflicts pain, while his masochistic identification with her registers his desire to transcend his own boundaries and his revelry in her physical fluidity, as much as it suggests a desire for plain pain.

Bellmer’s photographic project simultaneously produces and affirms the “illusion” of timelessness and physical fluidity he yearns for, staging over and over again the transgressive merging of the inanimate objects and the doll’s human form. In these images, Bellmer may witness the “mortal limitations of time and space extinguished” embodied in the doll, whose figure merges with her inanimate surroundings in the eternal photographic moment.

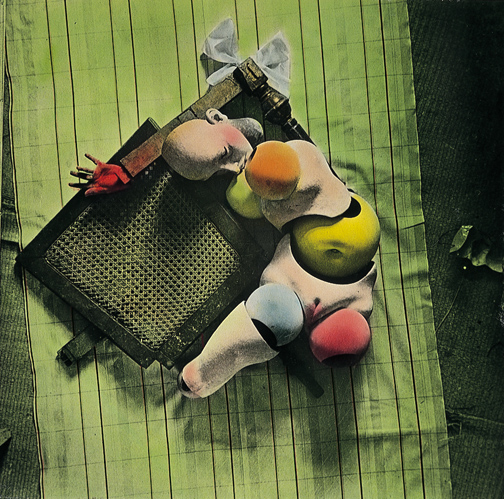

Plates V and IXThis doll has all the “necessary” parts of the human core. Here are the head, the globed breasts, the dimpled torso, the hips and sex, the stubs of two legs. But where in other photographs, Bellmer fits the ball-joints together to construct a coherent, if aberrant, whole, here he leaves the pieces disjointed so that the viewer beholds not only a fissured, fragmented body, but also its hollowed interior. Shading each ball-joint a different garish hue—lime green, pale blue, yellow, magenta—Bellmer creates a confusion between the ball-joint as body-part and the ball-joint as ball, a child’s plaything. For these are the bright colors of the nursery, of Jack-in-the-Box, juggling balls, and alphabet building blocks. Arranged in an arc across the shattered pieces of a broken chair, the corporeal fragments mingle also with shards of wood. Not only is the doll collapsed like the chair, but her form incorporates its wooden elements. Her rouged, delicately tensed hand, which blooms at the end of the wooden beam, and the white silk bow that caps the apex of the wooden angle enact a slippage of meaning between arm and chair, angle and head. But Bellmer does not allow us to forget the doll’s humanity. Her sex, knee, and cheek have the pink flush of girlhood. Her hand is taut. The doll is caught firmly between the realms of subject and object, animate and inanimate, human and thing. At the same time as the decidedly insentient objects “ball” and “chair” seem to reduce the doll to the order of things, their incorporation with the components of her human body suggests their reversed transformation from object into body-part.

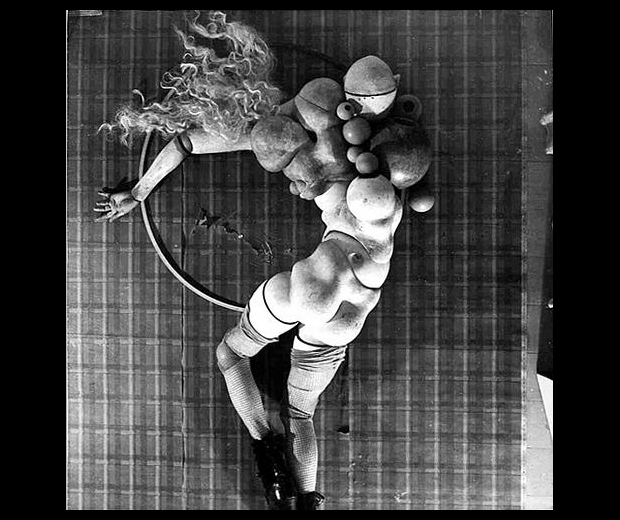

Plates VII and XIBellmer stages similar equivalences between the inanimate and animate worlds throughout Les Jeux de la Poupée. In plate VII, the doll’s flailing ‘upper legs’ are entangled in the branches of a small tree. Though they are not so literally merged as the chair and the doll’s torso appear, the gestural and morphological mirroring forges a metaphorical equivalence between branch and limb. Plate XI shows the doll’s body, here truncated, heaped in the center of a white comforter. The pale body, only lightly tinged with pink, is a pillowy extension of the comforter. In yet another image, similar to plate V, Bellmer arranges the doll’s body again in an arc, this time conforming it to the curve of a hoop. Again he has endowed her with a full human form: her arm bends, her blonde hair streams forward, and her legs are sheathed in stockings. But where her torso should swell into prepubescent breasts, it instead explodes into scores of spherical ball-joints. Her body seems to have burst its seams, issuing forth its inner contents in bulbous pustules.

This last vision of corporeal rupture manifests the essential assertion that underlies each instance of subject-object, animate-inanimate mingling. It is the vision of the of what Bellmer felt to be the “sole existing instinct, that of escaping the contours of the self, …to be less at the mercy of the pain and boundaries of the Self.” Each act of violence Bellmer performs on the doll’s body is an attempt to realize the physical fluidity he craves. He grants his doll the relieving release from the constraints of a predetermined form that causes him so much suffering so that he may experience it vicariously through her expressive form. The passage out of the body—into another body, another object, another space—is, for Bellmer, the ultimate “liberating transference.”

Bellmer lovingly croons to his doll, “how shall I name you?”, but what his images and writing reveal is that there is no one name. It is precisely this fixing of meaning that Bellmer wishes to eschew through his subversive toy. The doll, never quite the same, writes the tale of Bellmer’s shifting desire, defined not by its affinity for a particular state of pain or mutilation, but by endless versatility. The doll’s anagrammatic form allows her to be always something else, her body becoming a different thing, even while it remains itself. For she is not simply a beribboned girl, she is also a blanket, a toy, a tree; she is pain and she is pleasure; she herself and she is Bellmer. Gazing at her ductile body held captive in the space of the photograph, Bellmer may approach the fugue of the “illusion,” “the span between life and death,” the “other side,” where all boundaries are breached.

* * *

Plates XIII and X“The distress we feel at the duplicity of appearances is far too great to be exhausted by the usual poetic metaphors, and demands that we undertake a radical re-evaluation of our concepts of identity.”

“The essential point taught us by the monstrous dictionary of analogies and antagonisms that is the dictionary of the image, is that every detail, every leg, is only perceived (and thus made available for use), in short, is only real if desire does not insist on regarding it as just a leg. An object that is simply identical to itself lacks any reality.”

The impact of Bellmer’s subversive tampering with form and content transcends the limits the doll’s body. He takes advantage of photography’s status as a documentary tool to elide his “duplicitous” reality staged in the photograph—where anagrammatic slippages between body-parts and subjects and objects occur—with the current reality outside the photographic space. The doll frequently appears in the familiar environs of the home: in a chair against floral wallpaper, in a doorway, sprawled on a bed, on a staircase. Objects of quotidian domestic life inhabit her world, alongside her—the pitcher placed on the right of the forked tree in plate X, the dishes laid out on a table in plate XII, the shards of the broken chair in plate V. (In other of the photographs not included in this series, she is seen with a top, in a bathroom, on a chair on a fur rug.) But these domestic settings—the spaces we associate with safety and comfort—only emphasize our anxiety in front of these photographs. These environs naturalize her, suggesting that this impossibly depraved thing is in fact real. The halls and doorways are uninviting spaces full of shadows and devoid of people. The doll’s presence in them confirms that these would-be homey interiors, already imbued with a sense of foreboding, are not what we know them to be, but are sites of sinister and illicit activity. Just as the familiar form of a little girl clad in bow, white socks, and black patent leather shoes has been radically reduced to something terrifying and aberrant, so the home is no longer the zone of comfort and safety, but a place of violence and sorrow.

So far I have discussed these photographs in terms of Bellmer’s viewership. But Bellmer was and is not the only audience of this grisly montage. For we too consume the doll’s exposed body, immortalized in the images, joining Bellmer in his flagrant voyeurism. Aligning the viewer’s gaze with his own, Bellmer dupes his viewer into participating in his disturbing fantasy, gleefully stating, “No one will be able to avert their gaze quickly from this synthetic Eve who, however hurtful she may be, suffers from her own, impossible formula.” As much as the doll is a terrifying and piteous form, she is also a tantalizing and sexualized body. She appears in Les Jeux de la Poupée coquettishly propped against a tree, her clothes discarded at her feet; suspended in a tree, her vulva and breasts bob in the foreground like fruits to be picked and savored; full-frontal in a box, she cocks her hips in a jaunty S-curve, garish pink flush at her sex. Like the classical effigies of Venus, the doll’s pale and denuded form seduces the viewer, ensnaring him/her in an explicitly erotic visual interplay. But, offering the cadaverous Medusa for contemplation in place of the pristine Venus or the coyly ivied Eve, Bellmer’s photographs pervert this archetypal desire for the sublimated female form, catching his unsuspecting viewer in the exchange of sadomasochistic desire and pleasure that passes from him to his doll and back again. For Bellmer’s Eve is a twisted and suffering being. There is nothing natural, primordial, or celestially ordained about her. To be titillated by her mutilated and corpselike form is to admit attraction to her pain—to participate in the same sadistic play as Bellmer.

Plate XIIIBellmer not only makes his viewers of his images complicit in his sinister task, he also explicitly implicates them in the nightmarish fantasy world of his creation as active agents. In one particularly striking image (plate XIII), the four-legged doll leans against a doorframe, both sets of hips (lower and upper) jutted in a provocative contraposto. Her backside is turned to the viewer and she is dramatically illuminated from the left so that the contours of her buttocks, her hips, and her thighs are exaggerated. Superimposed over this image is the black silhouette of a carpet-beater. The sexual and sadistic connotations of this image are overt; this doll awaits a spanking! But what the image leaves ambiguous is the identity of her tormentor. The carpet beater is pulled back from its target, looming largely on the surface of the picture plane. Occupying the liminal space between pictorial realm and the viewer’s location in the three-dimensional world, this silhouette illusionistically elides the viewer’s ‘real’ space and the ‘imaginary’ realm of the doll. In this joint realm, it is the viewer who is invited to wield the domestic weapon and make his/her own sadistic contribution to the doll’s form. This invitation to participate in Bellmer’s sadistic relationship with his doll denies any claim to passivity the viewer of these images may claim; this image suggests that even to look at this body is to enact violence on it. In this moment, Bellmer has caught the viewer in the “impossible formula”—the endless circuit of inflicted pain—both he and the doll suffer from. For as we stare—transfixed, horrified, fascinated—performing the violence of voyeurism, we must ask ourselves: This is Bellmer’s fantasy world, but is it also ours? Are these aberrant shapes the forbidden forms we too desire to abuse, to possess, to mimic?