Alexandra Tatarsky

Babble On

ISSUE 32 | SMALL WARS | SEP 2013

The proper name of God (given by God) is divided enough in the tongue, already, to signify also, confusedly, “confusion.” And the war he declares has first raged within his name: divided, bifid, ambivalent, polysemic.

– Derrida

In Moscow in 1965, the poet Genrikh Sapgir began to translate a cycle of Biblical psalms into a Soviet-Jewish tongue riddled with howls, profanity, silence and smoke rings. These new versions entered into a complicated conversation with their predecessors, accruing linguistic shrapnel in the shattering of sacred text. The fragments that remain of the original lines dot down the page, disfigured. And in this way the psalms demand that we form new images of their broken pieces.

Linguistic confusion allows us to read words that seem to belong to no language in several languages, all at the same time. And so the words begin to talk amongst each other, internally debating their meanings. Visually and aurally, the meanings collide and fight for territorial ownership, and in doing so they expand each other. The simultaneity of possible meanings allows a single word to contain a conversation.

What happens when we read a word in more than one language at the same time? Or when we read a word by its shape instead, or by its sound? There is a battle between associations. In the intimacy of combat, each tongue fights to obliterate the other. Each seeks to define its borders by marking the end of the other, or through merging to annihilate both. But perhaps coexistence between opposing tongues, between contradictory interpretations of truth, can expand the realms of both.

What if we thought about translation as the translation of meaning from many languages into many languages? That is, what if we read an individual word as the possibility of many other words? And allowed this associative logic to make strange the known language, and ever spur our desire for a deepening closeness with the unknown?

Words then begin to function like tea leaves, or coffee grounds or tarot cards or ink blots, a folk etymology that reveals truths based not in scientific proof but rather in our associations with an image. However, this personal web of imagined possibilities can impede communication based in collective agreements about meaning. How then to reside at once in our shared world, in language as we know it to make sense and sentences, and in the possibilities of a world found(ed) through creative interpretation? How can the mystical be translated into the material? How do we bring experience of the divine down to earth?

To my ear, Sapgir’s poetic language embodies the struggle to articulate the divine name in human tongue(s). Through careful gibberish, he restores the memory of the divine name, itself unpronounceable.

* * *

The difficulty of finding a form with which to clearly present these poems for discussion underlines the philosophy of language they put forth: that the interconnectedness of discrete languages, in both a historical and mystical sense, makes explication in any one language necessarily incomplete.

Sapgir was writing in (un)standard Russian. Because of the way Sapgir’s poems mirror the Russian text, I assume he was reading the psalms in the Russian Synodal Version, and thus performing an intralingual translation. But from his highly regarded translations of Yiddish poetry and his Jewish background, we can surmise that Sapgir was familiar with the Hebrew text as well, at least in sound or shape. His project can be understood as seeking to restore a Jewish meaning or relevance that has been lost as the text was Christianized in its passage from Hebrew into the Greek, Church Slavonic and Russian of the Orthodox Bible.

In very broad strokes, a Jewish relationship to language locates meaning in the body of the letter, itself the substance of divine creation and so a Jewish philosophy of translation can be described as deeply literal, urging the reader back towards the original. A Christian philosophy of translation, by contrast, would favor a more “poetic” translation, transmitting the spirit of the original into any and all languages.

In this simplified binary, Sapgir is forced to perform a poetic (Christian) translation of a Hebrew text in order to restore its Jewish resonance. Another way to put this is that his translation points towards all that has been lost of the original text, through omission, silencing, distortion and distance. Communicating this loss is the best translation of what the sacred text (Hebrew by way of Russian) might mean in a Soviet-Jewish language.

See below to see the complete Russian Synodal Versions of the Biblical psalms, and on the opposing side Sapgir’s original rewriting—accompanied by full Biblical text in English from the King James translation next to the Sapgir equivalent, my original translation from his Russian, or “Soviet-Jewish” version.

* * *

Psalm 1 teaches us how to read the rest.

|

1. Blessed is the man who walketh not in the counsel of the ungodly, nor standeth in the way of sinners, nor sitteth in the seat of the scornful. |

1. Blessed is the man who hath not walked in the counsel of the ungodly

somehow nor attendeth meetings of the ZAKT and cooperative nor sitteth at the table of the Presidium— but simply sits at home |

In Sapgir’s text, the way of sinners has been “translated” into Soviet as the meeting of the ZAKT, the Soviet housing rental authorities and cooperative. The seat of the scornful is the table of the Presidium, the head Soviet legislative body. And the only way to avoid them is by staying home. The words for “at home” [дома] and “presidium” [президиума] are linked by their endings, forming an alliance between them.

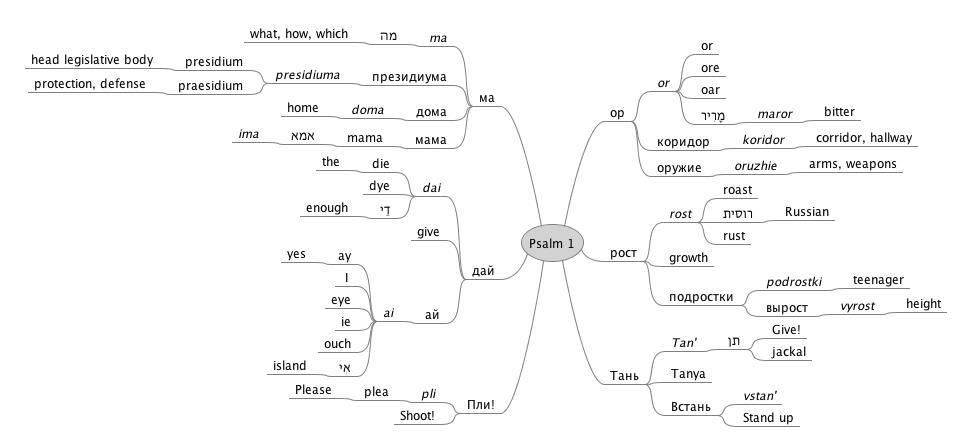

If we map out just some of the interlingual wordplay it might look like this:

Sapgir is building a web of associations whereby we are all culpable, a world where there can be no “blessed man.” If the man avoids participation in the legal bodies that control housing by staying home, his passivity provides an intimate and ongoing entanglement with their activities.

Specifically, the two words are linked by “ма,” two ma’s, mama, as if family has been replaced by the (s)mothering institute of the state. And in Hebrew, a homophone for מה [ma] meaning what, which, how has this happened? The Hebrew expresses incredulity at the Russian meaning that invades the sacred space of the home. And yet it is in this mama that there is also the possibility of communication between these spheres, as ma ma contains the basic units of sound created by the closing of lips (m) and their opening (a). Among the first sounds a baby can make when learning to speak, ma is the mother of all language.

|

2. But his delight is in the law of the LORD;

3. And he shall be like the tree planted by the rivers of water, that bringeth forth his fruit in his season; 4. The ungodly are not so: 5. Therefore the ungodly shall not stand in the judgment, |

2. Neighbors take up ar— 3. Three fearsome 4. Burn a lamp 5. And there— |

The blessed man stays home while down below neighbors arm themselves. He meditates calmly on the word of G-d while youths beat each other to death. And in the telling, words begin to fall apart.

The word for weaponry [оружие] cannot be fully said. Instead, it hides at the end of the corridor [коридoр]. Again, the linking of two words in sound brings our attention to a fragment: “oр” or or, the very conjunction used to signify linked alternatives. In English and German the word is gold. In Hebrew, it completes the word for bitterness [מרור, maror]. The Hebrew reading is bitter in the mouth while the Russian word begins violence.

|

6. For the LORD knoweth the way of the righteous: but the way of the ungodly shall perish. |

6. All from the roots of your hairs to the stars you slowly withdraw in height… 7. Below teenagers—ruckus and whistling beat iron on iron one on the other |

The blessed man “withdraws in growth [рост],” while the beating continues among teenagers [подростки]. As the grown man in his pious heights stretches towards the heavens he shares language with the teenagers below. The godly and the ungodly are linked in their roots. Both contain rost, pronounced like our English roast. In German, the same sound means “rust” and in Hebrew, “Russian.” This meeting of spiritual growth and adolescent violence spurs a multilingual association with burning, tarnishing, and the Russian language: a corrosion of communication. And yet its crumbling allows this new construction, recognition of an inner connection.

|

“Give it to him! Give it!” “I’ve!” “Shoot!”— |

The shouts among youths are affirmed by their own pieces. One calls out “Give it to him!” [дай!]. In English, дай sounds like dai, die and so the colloquial “give it to him” is revealed through the association of homophones to be an offer of death. The Hebrew reading shouts “Enough!” [דַי] in the same breath. And the reply is a fragment of that shout: ай! Its sound embodies these oppositions. “Ай” is at once an affirmation and a cry of pain: ai, ay. In English, it is the sound of I and eye. In Hebrew: אִי, island. This complicity and pain, recognized by the seeing self, is itself bereft, at sea. See: an island. And all this is already embedded in the command дай! (give it to him, that is, kill!, which is to say, die!). The oppositional meanings reveal: to kill is to be killed. Enough! of all this. “Shoot” [Пли!—] is pronounced pli, a plea, the sound of an aborted Please.

|

8. “Tanya! Ah, Tanya!”

9. Stand |

The psalm closes as the blessed man calls out to Tanya to go and shut their view outside. And Tanya [Тань] folds into her obedience, hiding inside the word with which she goes to stand [встань] and shut the vent. The blessed man stays home with the word, and sees nothing of the world. The original psalm is silent on this matter. Sapgir’s version has extended beyond the bounds of the biblical shape and so undermines the division between the righteous and the ungodly.

* * *

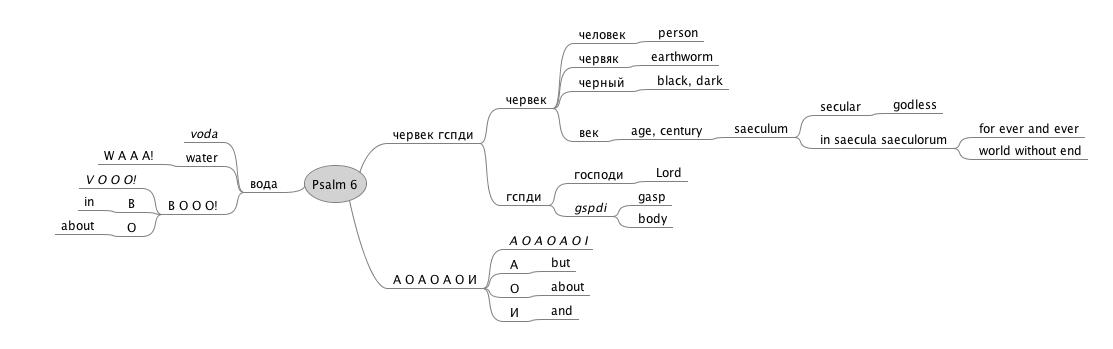

In Psalm 6 the disintegration of the word continues. Sapgir uses language as a physical material to embody the Biblical line “Lord in death there will be no memory of Thee.” As man ceases to remember G-d, the words for both man and G-d fall apart; they lose pieces (letters) of themselves as if eaten by earthworms. If God is not remembered in language, (and in whose language, is the question) it is as though He has been laid to rest, allowed to decompose in a fleshly sense for His presence relies on our enunciation of His name, here left to rot.

| 1. O LORD, rebuke me not in thine anger, neither chasten me in thy hot displeasure. |

1. Lord in death there will be no remembrance of Thee earthworman-lrd earthworman-lrd earthworman-lrd |

The creature that remains after death is the earthworman [червек], a darkly humorous merging of man [человек, chelovek] with earthworm [червяк, cherviak]. Or perhaps this sound combines black [чер, cher] and century [век, vek]. Put together, this dark age gnaws its way through the name of G-d, eating a hole through His unspeakable vowels: lrd. G-d dependes on man's continued engagement with the unknown, the unpronounceable, His name. Forgotten in the mouth, the Word disintegrates like flesh: earthworman-lrd.

|

2. Have mercy upon me, O LORD; for I am weak: O LORD, heal me; for my bones are vexed.

3 My soul is also sore vexed: but thou, O LORD, how long? |

2. Nor of water— W - A - A - A - A

3. Nor of sunlight— |

Attempting to remember water, the word is unable to complete itself: W-A-A-A-A. Recalling sunlight becomes its own silencing: SUNXCHSH – SH – SH - SH! The divine name, itself only a recollection, falls apart entirely.

|

7. Mine eye is consumed because of grief; it waxeth old because of all mine enemies.

8. Depart from me, all ye workers of iniquity; for the LORD hath heard the voice of my weeping. |

7. Who shall give Thee thanks in the grave O Lord? earthworman-lrd earthworman-lrd earthworman-lrd

8. Parched bones— |

The rest of the original psalm is abandoned, forgotten. The only lines that are quoted by Sapgir are those that affirm the impossibility of remembrance. By the last, Lord succumbs to the sound of parched bones: sklkst.

| 9 The LORD hath heard my supplication; the LORD will receive my prayer. |

9. Spare me O Lord A – O – A – O – A – O – I |

Lord gives way to a wail: A-O-A-O-A-I. Phonetically the letters spell out questioning and trepidation before the self: ow-ow-why or uh-oh-uh-oh-uh-I.

In Cyrillic, each of these letters is itself a word. “A” means but. “O” is about. And “И” is and. Put together, the string of letters attempts to recall the tetragrammaton from the grave but about but about but and grasps towards something it can’t quite say. Where the Hebrew theonym [יהוה, YHVH] lacks vowels, Sapgir’s supplication addresses G-d in all vowels, as if seeking the forgotten sounds.

And again an alliance is made between opposites, between the self and the enemy, as the closing image of revenge in the Biblical psalm is substituted for a call to “save” that crumbles into bone and consonants.

| 10. Let all mine enemies be ashamed and sore vexed: let them return and be ashamed suddenly. |

10. In these days— E – I – E – I – E – I – I – E – I – I

11. Save – skllkst |

* * *

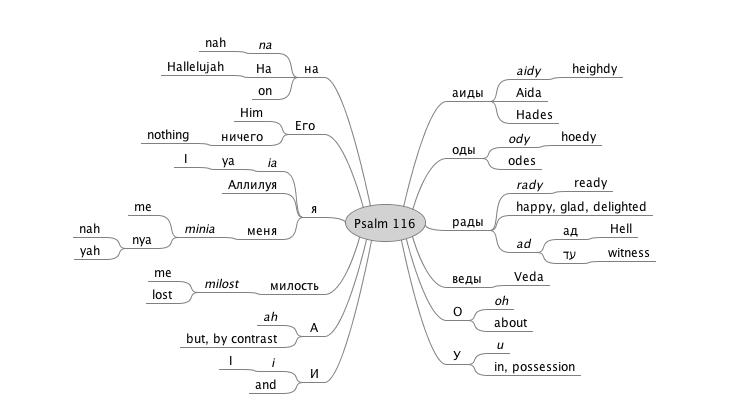

This play of letters that describe only their ever-approaching distance from the divine continues in Psalm 116.

| 1. O praise the LORD, all ye nations: praise him, all ye people. |

1. O praise the Lord, all ye nations: aidy and ody and happy and vedy 2. Praise him all ye peoples and on O and on U and on I and on A |

Attempting to praise the lord again results in a distorted tetragrammaton of vowels. Again, each letter here in Cyrillic is a preposition or conjunction. In Russian, О means about, У means in, И means and, and А means but. So calling out to a God whose name we cannot say sounds something like about in and but—as if approaching and ever seeking more but— the search is cut off.

|

4. Not desiring anything Hallelujah roll drunk on the floor I Hallelujah and in me – from me all nations of the eons cry out: God – Ha! Ha! Ha! Ha! Hallelujah! |

Psalm 116 ends in a drunken guffaw, slipping into praise as if laughter at or with G-d becomes the only way to pray. This interpretation is the collision of “Ha” read at once in the Roman and Cyrillic alphabets. In Russian, it is the preposition “on.” So perhaps God – on! On! On! On! as if having finally made contact. Halleluyah! But to the eye that reads English, the rejoicing is a visual mockery. It collides with the Russian meaning to form a moral that can only exists between the two linguistic realms: to go on praising His name, one can only laugh. It is as if the suggestion to repeat the name of G-d ("God- and on and on and on and on") is laughing at itself with another tongue, for it does not actually do what it says. It admonishes but does not act.

* * *

It may appear that we are reading too much into all this, as the phrase goes. When I read a poem in a language that is not my own, my grasp is just weak enough that I am never exactly sure where I am going. Much like walking in a foreign city, it is very easy to get lost, but the detours are more illuminating than the correct route. In an unknown land, the smallest things acquire an entirely profound quality they did not seem to possess at home. A pebble in Russia can be a site of revelation (this has been my experience, at least). And the intense significance found in small things is a source of great delight and embarrassment for the traveller, who vaguely remembers there were pebbles back home, but that they failed to communicate Truth with quite the same expansive fervor. The slowness of sounding out a word allows the reader to register first the image, then the sound, and only then the emergence of meanings. Reading a word in a foreign tongue allows one to linger on things that would normally attract little attention. As in Babel, the City of Confusion, the City of God, a single letter forms a path towards meaning that at once obscures and illuminates the destination. The task is to reside between the realms of foreign and familiar, to turn the seeking gaze of the stranger upon one’s home and to recognize the known that ever resides within the unknown. This in turn spurs desire, a longing and a reaching for that which ever exceeds our understanding.

I have used Sapgir’s multilingual psalms to discuss a mode of reading that allows the eye to estrange the familiar and familiarize the strange must reside in the space between this opposition. Its logic make sense of contradiction. There, between the poles of us/them, known/unknown, man/divine, material/mystical, neighbor/stranger, it is possible to understand misunderstandings as the site of insight.

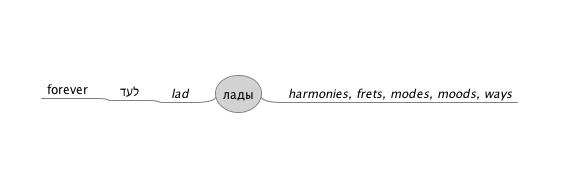

His final psalm closes with a shout of worshipful rejoicing, a call to make meaning in different modes at the same moment and forever.

|

Алилуйя (12 раз на все лады) |

Hallelujah! (12 times in all ways) |

|

Псалом 1

1. Блажен муж иже не иде на сборища нечестивых и не стоит на пути грешных и не сидит в собрании развратителей, 2. но в законе Господа воля его, и о законе Его размышляет он день и ночь! 3. И будет он как дерево, посаженное при потоках вод, которое приносит плод свой во время свое, и лист которого не вянет; и во всем, что он ни делает, успеет. 4. Не так--нечестивые; но они--как прах, возметаемый ветром. 5. Потому не устоят нечестивые на суде, и грешники--в собрании праведных. |

Псалом 1

1. Блажен муж иже не иде на сборища нечестивых |

|

Psalm 1

1. Blessed is the man who walketh not in the counsel of the ungodly,

2. But his delight is in the law of the LORD;

5. Therefore the ungodly shall not stand in the judgment,

6. For the LORD knoweth the way of the righteous: |

Psalm 1

1. Blessed is the man who hath not walked in the counsel of the ungodly |

|

ПСАЛОМ 6

1. Господи! не в ярости Твоей обличай меня и не во гневе Твоем наказывай меня. 2. Помилуй меня, Господи, ибо я немощен; исцели меня, Господи, ибо кости мои потрясены; 3. и душа моя сильно потрясена; Ты же, Господи, доколе? 4. Обратись, Господи, избавь душу мою, спаси меня ради милости Твоей, 5. ибо в смерти нет памятования о Тебе: во гробе кто будет славить Тебя? 6. Утомлен я воздыханиями моими: каждую ночь омываю ложе мое, слезами моими омочаю постель мою. 7. Иссохло от печали око мое, обветшало от всех врагов моих. 8. Удалитесь от меня все, делающие беззаконие, ибо услышал Господь голос плача моего, 9. услышал Господь моление мое; Господь примет молитву мою. 10. Да будут постыжены и жестоко поражены все враги мои; да возвратятся и постыдятся мгновенно. |

ПСАЛОМ 6

1. Господи в смерти не будет памяти о Тебе

2. Ни о воде -

3. Ни о солнце -

4. Ни о небе –

5. Ни о самой тончайшей травинке -

6. Ни о снежинке

7. Кто будет славить Тебя во гробе Господи?

8. Иссохшие кости -

9. Пощади меня Господи

10. В эти весенние дни -

11. Сохрани - склкст |

|

Psalm 6

1. O LORD, rebuke me not in thine anger, neither chasten me in thy hot displeasure. 2. Have mercy upon me, O LORD; for I am weak: O LORD, heal me; for my bones are vexed. 3. My soul is also sore vexed: but thou, O LORD, how long?

4. Return, O LORD, deliver my soul: oh save me for thy mercies' sake. 7. Mine eye is consumed because of grief; it waxeth old because of all mine enemies.

8. Depart from me, all ye workers of iniquity; for the LORD hath heard the voice of my weeping. 10. Let all mine enemies be ashamed and sore vexed: let them return and be ashamed suddenly. |

Psalm 6

1. Lord in death there will be no remembrance of Thee

2. Nor of water—

3. Nor of sunlight—

4. Nor of sky—

5. Nor of the finest blade of grass—

6. Nor of a snowflake

7. Who shall give Thee thanks in the grave O Lord?

8. Parched bones—

9. Spare me O Lord

10. In these vernal days—

11. Save – skllkst |

|

ПСАЛОМ 116 1. Хвалите Господа, все народы, прославляйте Его, все племена; 2. ибо велика милость Его к нам, и истина Господня вовек. Аллилуия. |

ПСАЛОМ 116

1. Хвалите Господа все народы: |

|

Psalm 116

1. O praise the LORD, all ye nations: praise him, all ye people. 2 For his merciful kindness is great toward us: and the truth of the LORD endureth for ever. Praise ye the LORD. |

Psalm 116

1. O praise the Lord, all ye nations: |