Casey Lange

Careful

ISSUE 19 | DROUGHT | AUG 2012

Egon Schiele, The Embrace (Lovers II), 1917

1. Caring without feeling?

You have a friend who lives far away, so the way that you keep in touch and maintain that friendship is by talking on the phone. You care about them and want them to know that, so you should call them. At least, you were strongly feeling that you should yesterday or a week ago, but just then you didn’t have time to call. Today you’ve got some time, and you know that’s still true, that you care about them, but you’re kind of stressed out about other things, or maybe you’re thinking a lot about something or someone else that they’re not particularly interested in hearing about, or maybe you’re just feeling self-involved and pensive—for whatever reason you don’t particularly feel like talking to them, and moreover if you did call and talk to them, you’re worried that your lack of present active desire to talk to them will be evident. What if it seems forced, what if you seem distracted or uninterested? What if you apologize for sounding hollow or distracted or bored and reassure them it’s just your mood right now but really you do care about them...and it seems like you don’t “mean” it, like you’re just trying to please them? (Maybe you generally assume that if you say something while you’re feeling it, then your sincerity will be unmistakable to whoever is listening or reading.) What if, in that moment, you really are just trying to please them?

...You must think about this a lot! In any case I’m going to start out with something a bit harsh: Right at the end there, the self-centered and narcissistic nature of your anxiety becomes apparent.

2. Care

You care about someone: that means something like, you try to preserve their well-being and encourage their flourishing. In general you want them to be well and happy. Now there must be a reason for this. Probably, at some point, you realized that you felt some strong affection toward them; you found that they and/or your interaction with them filled you with something exciting, uplifting, warming, what have you; we need not focus on true loves or cataclysmic friendships. Your life is better for your knowing them, and you are grateful to something that they are in your life. My point, to put it very broadly, is that you feel some positive thing toward them, and this is the source of your particular relation to them.

Part of this relation is that you care about and care for each other. You care for them. You are attentive to their needs in the dual sense that you pay attention to what their needs are (which may, depending, require more or different attentive effort than simply listening to what they say they want or need) and that you attend to their needs, doing what you can to fulfill or help them fulfill those needs.

Now two difficulties can arise with respect to caring for the person you care about. One is that sometimes they require care when you are not particularly feeling anything about them. That does not mean you feel negatively toward them (though you might); they might just not be particularly on your mind or emotive center at the moment. Moods fluctuate, our attention is divided, our eyes are drawn to novelties, the surface of consciousness is a forgetful place, sometimes we are simply empty. The second difficulty is that even when your affection is full, salient, overflowing, and you feel a spontaneous urge to care for that person, there is a question whether your care is correctly oriented, namely, toward the person and not toward yourself or your feeling.

3. Narcissism and Loneliness

“You are trying to safeguard your expressions against dilution or hollowness.” What do I mean by that? I mean that—as you acknowledged with a vaguely-comprehended discomfort—your criterion for the sincerity or authenticity of an expression is that it arises spontaneously from some emotion. And of course you care about being authentic.

Now that is not all wrong. A relationship is not a rule-governed thing, and a friendlike relationship that is based purely on feelings of obligation or rote adherence to convention is a failure. There’s good reason for the discomfort you feel about, e.g., certain couples who seem to persist as couples just because it does not occur to them not to do whatever a boyfriend or a girlfriend are supposed to.

So I am not saying anything as simple and stupid as, “You are being selfish. Quit thinking about yourself and put others first for once.” For one thing everyone knows that selfishness is bad, but for another thing everyone who’s thought about it for three continuous seconds knows that it’s not so simple as selfishness vs. selflessness, atavism vs. altruism. It’s conventional wisdom these days—and not just as part of capitalist success-worshipping—that you should make yourself happy and that, moreover, if you’re going to be any good for other people there’s a certain amount of self-care you’ve got to enact. Besides, people are more interesting when they’re a little vain, at least enough to notice that they glitter and to want to scintillate a few rays onto the people around them. People are pretty interesting and should not be embarrassed to show it.

But the real reason not to be completely self-absorbed and narcissistic, and why if you’ve really thought about it it actually scares you quite a bit, and probably part of the reason why people are so universally disturbed by and condemning of it, is this: We are essentially social creatures (this is why we have language and articulate thought in the first place) and we do not like being alone. To be utterly self-absorbed, to be the only thinking feeling being in the universe, is to be utterly, utterly lonely.

But by saying that solipsism goes against your nature and leads to despair, and that this is a paramount motive not to fall into that, I don’t mean to give the impression that avoidance of that despair is also the paramount reason and motive to care for others in a committed and not merely impulsive sense. There is a positive motive as well, and it is exactly what you'd expect: as essentially social creatures, our positive well-being and flourishing depends on caring for and being cared for by others.1

4. Feeling without caring?

Let’s look at the second difficulty. What about manifestations of care that do arise from overwellings of spontaneous feelings of care, affection, friendship? The sort of feeling that seems to bear on it the stamp of its own validity, that seems to say “Maybe there are plenty of good times to distrust your instincts; now is not one of them.”

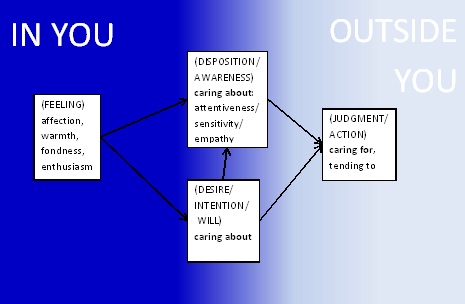

I argue that there is good reason for caution here too. This is not to say that you should not act according to your feelings, especially feelings like that. Intuition is a thing, epiphany is a thing. But when acting on feelings about other people, it is important to examine their source and their orientation, to make sure that they are properly connected to the other person and to the relationship that entwines you. You felt some sort of affection for them, which gave rise to the attitude of caring about them. That gives rise to an awareness of and sensitivity to their well-being and a desire to tend to that well-being. Then, when you notice that they are in need, you judge how you can help, and do so.

Figure not to scale. Location of gradient median approximate.

The danger is that you identify caring entirely with your feelings of affection and concern. In that case, since the caring is entirely identified with a feeling inside you, the criterion of its success or completion can lie completely inside you as well. So that whenever you are done with the feeling, you are, for your part, done with the act of caring—while relative to the needs of your friend the act may be nowhere near complete. Maybe you are done caring about the other person, but the other is not done being cared for. In the extreme case, from start to finish the felt need to care (and from your perspective the action of caring) may completely satisfy itself without ever leaving your mind, without any outward expression.

Maybe you’ll say that I must have an especially insensitive, blind, un-self-aware person in mind when I describe this. But I think that it is more common than we might think. Real forms of harm and badness often don’t look, especially up close in the first person, like we imagined them. Now there are certainly times when we know something is bad and unjustified and we do it anyway despite our judgment. But it would be kind of stupidly easy to avoid doing bad things if all we had to do was to only choose actions that we think (at first or second blush) we have good reasons for.

In the mid-19th century a writer named Johannes Climacus, in a book called Concluding Unscientific Postscript to the Philosophical Fragments, wrote:

But acting in the eminent sense belongs essentially to existing qua human being. Through acting, through risking what is decisive (of which every human being is capable) with the utmost subjective passion in full consciousness of an eternal responsibility, one learns something else...

The meaning of care—like that of many other ethical concepts—exists beyond the subject. Its meaning is, in this sense, objective. “Acting in the eminent sense” means (some scholastic terminology) in a higher sense than “formally,” i.e. merely by definition. When we act qua human beings, we always act in and in the face of ignorance. We can never know, while we are doing it, whether what we are doing is really caring, because we don’t know whether it will successfully contribute to the well-being of the person it is directed toward. There is no way to reduce the criteria of care to things we can wholly appraise by thought and introspection so as to be certain that we are doing what we intend. To care is always to aspire to care, to aspire to something that we don’t fully know. We risk finding out that our appraisal of our friend, of their needs, of our ability to help, was incorrect.

5.Tricks for feeling when you need to care

One thing I’ve been trying to clear up is the idea that for any action to be an authentic, effective expression of care (that is, as I tried to show earlier, care being an intersubjective/interpersonal thing, it cannot be an authentic expression of care unless it is sincerely aimed at being effective for the other person), it is necessary to work yourself up into some intense emotional state or to strain to be at the height of your communicative performance. Or in other words, I am against the tempting but misguided idea that the solution is simply to, in the moment, TRY HARDER. (We are complex spatiotemporal processes, comprising many moments that interact with each other.) You can see how that requirement could in fact hinder you from caring well. There are times that what a person needs most of all is your ear or your presence or your voice however clumsily, and if you can provide that it would be uncaring to withhold it just because you are not the version of yourself that you like other people to see.

That said, much of the time it is helpful to recall why you care for someone. And by recall, I mean re-evoke, not merely remember in a cognitive or verbal way. To call not facts but moments or experiences back to oneself, or to call oneself back to those. Here are some practical techniques for that. (Don’t just read through the list. Try it, now: think of a specific person you’d say you care about. Have one? Okay, begin.)

- Think of why you cared about his person originally.

- Think of the moment you met. If before you “really met” they were just some person you knew about, try to locate the moment when they went from being just some person in the world, or some person you knew, to being “a real person,” someone whose mind you could imagine. (Try, but maybe you can’t recall the moment. It will probably still help to dwell on the massive distance between before and after.)

- Compare the person that you just knew about to the real person. Compare these two persons; marvel that they are somehow the same.

- Think of the moment when you first knew what was going on in their mind intuitively.

- Perhaps you met them through mutual friends: recall the first time one of you directly contacted the other to hang out.

- Recall a time you were together when at least one of you was terrified.

- Clear your mind and recall your common history. Think of people you know because of them. (This will help you recall the moment that they introduced you. Introductions are often happy or somehow emotional.)

- Write a character portrait of them. Imagine a novel with you as the protagonist. How would their character be introduced?

- Imagine a novel with them as the protagonist. How would your character be introduced?

- Imitate their laugh. Imitate a some other characteristic noise they make, such as when they are surprised or interested.

- Think of things you have learned from this person. Think of things you learned not from them but in their presence. Think of practical things too.

- Think of what you have taught this person.

- If you were to write even a sappy poem or song about this person, what details would you include?

- Look back at something you wrote around a time when you were feeling close to them. It might be about them, but it doesn’t have to be. Look back at a book you were reading, or listen to some music you were listening to a lot of during that time.

- You probably associate them with a place. Remember walking around that place.

Good luck.

1This is not to deny that beautiful perversions can arise from pushing solitude to its limit, or that solitary discourse can be a very fruitful way of exploring/mapping the entire apparatus of human being as it is reflected or encoded in a particular mind.