Root Barrett

Would You Like Salvation With That?

ISSUE 18 | NO GODS NO MASTERS | JUL 2012

The Agnostic in the Tenor Section

Growing up, I heard plenty about God. I went to church most Sundays. I went to youth group too. At the summer camps I went to, we didn’t just play in the lake and wander around the woods—we also sang worship songs and learned to be better Christians.

Church-going was part of the texture of my suburban existence. So it seemed totally normal that I took communion and sang in the choir, even though I didn’t really care about God. Going to church was like going to school or extended family gatherings: I just did it.

I remember being told at some point that God should be at the center of my life. I wrestled with this, and concluded that I was more worried about pursuing True Love. If God wasn’t all right with that, I would just have to risk it. (Oh, the besotted recklessness of youth!)

I didn’t feel the pull toward God that I felt toward romance. The thought of orienting myself toward God left me cold. I imagined unhappily forcing myself to be good in a world with all the color drained out of it. And then what if God turned out not to exist? Worshiping God had no joy in it for me. True Love, on the other hand, promised endless delight. Like God, its power seemed to come from realms deep and mysterious. Unlike God, it would provide me happiness, relief from loneliness, and continuous sexual satisfaction. True Love would give me everything that I, an overfed suburbanite, felt that I lacked.

How had God come to be so empty for me? Why did I have no reverence, no awe? As a well-educated youth, I was immersed in the secularism of schools and national political life, a lover of scientific explanations—was that what killed my religious spirit? Or, perhaps, did I have no need for God?

Oh Lord, Won’t You Buy Me a Mercedes-Benz?

The ancient Romans, alongside their more fleshed-out deities, had lists and lists of what classicist Michael Lipka refers to as “functional gods.” These are gods whose whole existence seems to have been a name, a function, and an incantation to use when their assistance was required. Vervactor, the god that breaks up the soil. Reparator, the god that restores. Sterquilinus—I shit you not—the god of manure.

Even their names are derived from what they do. Likely having no temples, holidays, priests or myths to themselves, they are stripped-down, bare-bones gods. They have none of the splendor or might of Iuppiter Optimus Maximus, none of the all-forgiving absolution of Ganesh. But there they are in the indigitamenta, the reference lists of Roman deities used by Roman priests. For all his humility, Sterquilinus is a god, and he was called on as one.

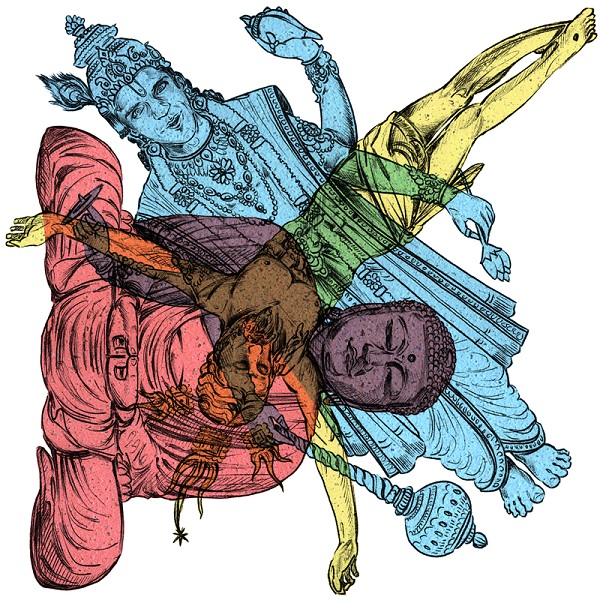

Illustration by Wesley Ryan Clapp

Contemplating the ancient god of feces, I wonder: what if the baseline thing a god must be to be a god is not mighty or awesome or good, but useful? What if our gods are not the ones we serve, but the ones who serve us?

Perhaps to be a god is to be an entity we turn to, an entity beyond us to whom we reach out for help.

This would explain my indifference to the God I grew up with. I never connected God the Father with anything I needed. The discussions around me were over how the Bible should be interpreted, how a Christian should behave, abortion, gayness, whether Hell exists. I went to a liberal church, so the general opinion on all of those could be summed up as “God is love, you can probably afford to relax.” Outside of church, though, the culture wars were blazing, and these were the issues that were treated as defining Christianity.

Clearly, I was interacting with God a little differently than the author of this ancient Roman cursing tablet:

I invoke you by the great names so that you will bind every limb and every sinew of Victoricus–the charioteer of the Blue team, to whom the earth, mother of every living thing, gave birth–and of his horses which he is about to race; under Secundinus (are) Iuvenis and Advocatus and Bubalus; under Victoricus are Pompeianus and Baianus and Victor and Eximius and also Dominator who belongs to Messala; also (bind) any others who may be yoked with them. Bind their legs, their onrush, their bounding, and their running; blind their eyes so that they cannot see and twist their soul and heart so that they cannot breathe. Just as this rooster has been bound by its feet, hands, and head... Now, now, quickly, quickly.

About this tablet, historian Courtenay Raia says, “...notice how specific this prescription is. There’s no importuning god for some sort of moral insight. [The author is] giving him critical, physical facts about how to be effective in this specific way.”

Christianity repudiates this pragmatic attitude. Raia puts it this way: “Instead of many, many gods who are helping you to get ahead in this world, you have one God that’s telling you to pluck out your eye and cut off your hand if these material things that make you bound to this world get in the way of your really big purpose, which is the next life.”

Screw that! Friends, I blame the satanic influence of MTV: as a teen I wanted women, money and cars. I was wholly immersed in a culture that was as consumerist as it was Christian. Idealizing True Love fit nicely with my general outlook: it was happiness brought from the outside. Orienting my life toward True Love didn’t require me to critique or change myself. It only needed me to add something new, to acquire a soul mate. I was always on the lookout for The One.

The God I’d grown up with, unlike the god called upon in that cursing tablet, was not going to intervene in this earthly business of mine. If Sterquilinus is the god you turn to for manure, the Christian God is the god you turn to for moral and metaphysical needs only: entry into heaven. Salvation.

As a lonely, lustful, smug little white child of suburban professionals, I was maybe too self-absorbed to think I needed to be saved. Maybe I was just too materially comfortable. “Who were the people that were first taken by this religion?” Raia asks of Christianity. “Well, its radical egalitarianism clearly is going to be appealing to all those people that Rome left out....there are way too many slaves in Rome, way too many dispossessed people.” To turn to the Father, the Son, and the Holy Ghost may require one to have given up on earthly delights.

Not that the concerns of this world don’t sneak in. God wins football games for Tim Tebow. He is instructed by millions each Sunday to “give us this day our daily bread,” a prayer that to me—like any prayer in the imperative—felt like arrogance. Who’s supposed to be the servant here, anyway? Doesn’t God call all the shots?

But the Lord’s Prayer can also be read as a necessary extension of God’s reach in a Christianity that has to bring practical functionality in through the back door. It is among the humblest prayers one can imagine—just one day’s worth of food, okay, God?—as unassuming as one can get while still giving God some real-world relevance.

I would later learn to understand the power in that humility. But with the aloofness of one who doesn’t really believe, I could insist on a kind of purity. While others brought their material needs to God in the midst of a struggle to turn toward God in all things and earn salvation, I would dwell on the contradictions of mixing the sacred and the profane. I agreed with the believers that God was far, far beyond us. The difference was that I was willing to leave God there.

But where is there?

Where is Your God Now?

Part of the distance I felt came from the abstractness and absolute moral perfection of the Christian God. But looking at other gods broadens the picture of what was going on. The Olympians and devas are not always better than humans. They don’t even always have to be more powerful; the sage Gautama Maharishi could cast a curse on Indra, king of the gods, covering him in vaginas. Gods are not all omniscient or good or majestic. They play tricks on each other, they sleep around.

What seems to be essential is that gods are beyond us, on the other side of some kind of boundary. Most ancient Roman temples, for example, had an architectural style that was extremely similar from one temple to another, and profoundly different from any other form of architecture in the city. Their adherence to architectural unity set up a symbolic and physical separation between the godly and the human.

Gods can live on Olympus, in those parts of the world we can’t perceive with the senses, or in the infinite expanse of the universe, but wherever it is, it has to be somehow separate from normal existence. Karen Armstrong notes that “Jews, for example, are forbidden to pronounce the sacred Name of God, and Muslims must not attempt to depict the divine in visual imagery. The discipline is a reminder that the reality that we call ‘God’ exceeds all human expression.”

That beyondness is critical. According to Michael Lipka, the imperial cult destabilized all of Roman religion by blurring the line between humans and gods. As more and more dead emperors got deified, these human gods took up space in other gods’ temples and took over their holidays. By the time Christianity came along, traditional Roman religion was falling apart.

But beyondness raises a problem, the one I brushed up against when I ditched God for True Love. God wasn’t just abstract, but remote from my affairs. It didn’t help to be in a church where we didn’t really talk about Hell, and where God’s love didn’t make itself known in earthly ways. I had the distinct impression that God was not going to meddle in my affairs one way or the other. I didn’t really think I’d be punished or rewarded for my behavior—otherwise I might have spent more Sunday mornings paying attention and fewer thinking about sex.

What was missing was a bridge between me and the beyond. Just giving God the flawed and wonderful personality of a Hermes, I think, wouldn’t have been enough. There were no holes in the boundary between my needs and God’s world.

This is a problem the Catholic saints seem to handle nicely: a whole series of non-gods you can ask for help finding your glasses or giving a speech, whose only technical ability is to turn to God and pass along your request. They’re allowed to be a little more tied to the realm of human affairs. They’re a bit like priests, managing the godly boundary from just over the other side.

Put another way, I think saints help Catholics deal with a contradiction built into godhood. Gods must function. We turn to them because they’ll forgive us or make the grain grow. But it can’t be our need that makes them gods; if it were just that, they’d be powerless. They have to be beyond us. But if they were really beyond us, they wouldn’t be susceptible to our prayers.

Looking at the vast array of gods in the world and the religions around them, I see innumerable ways of setting up boundaries around the ability to meet a need, each boundary with its own special openings to get our wishes across. Perhaps we must go to a temple, or ask a priest, or accept Jesus Christ as our lord and savior. Perhaps the right words must be said. Perhaps all we have to do is pray.

Whatever the specifics, it seems like everywhere we have set up masters who, under special circumstances, will do what we say.

My Buddhy Buddha

In college, I took up a Buddhist meditation practice. Suddenly, I had something that made a kind of religious sense to me: a path with no need of a god. There was a freedom here. For all my agnosticism (and occasional outright nonbelief), I had still identified with the Christian church. For all my devotion to True Love, I had begun to notice that it wasn’t making me happy. Now I could ditch the ambivalence in both these relationships and focus on developing lovingkindness. This was a down-to-earth path that didn’t ask you to believe in anything, especially not something so unverifiable as God.

...and then I learned about Green Tara. And Kwan Seum Bosal. And Avalokitesvara. Those flavors of Buddhism that don’t have straight-up gods in them do seem to call on quite a few Bodhisattvas. And it’s common across many traditions to begin practice with a statement like this:

I take refuge in the Buddha.

I take refuge in the Dharma.

I take refuge in the Sangha.

We turn for support to the omnipresent Buddha, the teachings of the Buddha, and the community of enlightened beings. Whoops! Armstrong claims that the transcendence the Buddhist seeks is the same thing the monotheists call God. We’re all just looking at the ultimate reality. In shifting to Buddhism, I thought I had risen above the question of God, that I no longer needed to depend on some untestable, faith-requiring Beyond. I thought I had gotten away from being saved. Had I stumbled into the same old God relationship from a different direction?

Concepts of God from certain streams of Greek philosophy and Hinduism also seem to be identified with this ultimate reality: God—sometimes even referred to as an “it”—is not a personality who responds to us, but an absolute to whom we turn for the experience of oneness. Is this the same dynamic, just in response to a different kind of need? It seems like every tradition has some kind of meditation practice tucked away somewhere: a way to empty oneself, drop selfish concerns, and let God in. A prayer I particularly love illustrates this kind of God relationship:

Praised be Thou, Lord, for our prayer fulfilled,

Since this our prayer is its own fulfillment,

Since by addressing Thee together, Lord,

We elevate our will, purify our desire,

And are of one accord.What more need we ask if that is granted?

What more need we ask, unless that it should last, Eternal God,

All through our days and through our nights?(From “O God of Truth” by Lanza del Vasto)

Spiritual teacher Eknath Easwaran, in a similar vein, talked of meditation practice as the practice of becoming a good flute for Lord Krishna. Meditation cleared him out so that Krishna could play.

What was my relationship to God now? On the one hand, here I was, doing the exact same thing as the God folks with a slightly different vocabulary. I was caught in setting up yet another beyond to reach for.

On the other hand, something else was going on here. The first koan I was given to work with goes like this:

Coming empty-handed, going empty-handed—that is human.

When you are born, where do you come from?

When you die, where do you go?

Life is like a floating cloud which appears.

Death is like a floating cloud which disappears.

The floating cloud itself originally does not exist.

Life and death, coming and going, are also like that.

But there is one thing which always remains clear.

It is pure and clear, not depending on life and death.Then what is the one pure and clear thing?

The response which indicated I had penetrated the koan was not “God.” It was not “ultimate reality.” It was not to somehow point beyond, or to point to any concept, any boundary or other structure. It was to raise my palm and SMACK! the floor. That SMACK! didn’t reference a concept, it created a space—a brief moment of being jarred into don’t-know mind, a moment where concepts are dropped. We take refuge in the Buddha, but if you see the Buddha in the road—kill him. Your enlightenment cannot be given from outside. We seek enlightenment—transcendence, ultimate reality—but we are always already enlightened. Enlightenment is right here, right now. We just have to let go of our ideas about it and see it.

For the contemplative God traditions, too, concepts fail—this is the boundary that Armstrong puts God behind. We are here, in our concepts, and God is there, beyond them. But according to Jesus, the Kingdom of God is within you. One might say that God is in us, is everywhere—it’s just that we can’t see God until our concepts drop.

And that’s the new contradiction, the new bit of weirdness at this edge of religious experience for me. Because at the moment the concepts drop, there is no “God.” There is no turning, and there is no beyond. No Buddha. The attainment of enlightenment includes the realization that there’s nothing to attain.

Perhaps the God of ultimate reality is just a convenient guiding idea, not a god at all, but a metaphor meant to poke people in the right direction: Do what you would normally do for a deity, and you’ll eventually catch on.

Or maybe that’s just me trying to explain away exceptions to a definition that I based on the Roman god of shit. I’m sure other exceptions are out there—the worshiped ancestors and spirits of the world seem to meet my definition. Are they all really gods?

Whatever the place of religious practice in relation to gods, I will say this: becoming a practicing Zen Buddhist has cleared away my hesitations about Christianity. A little less locked in concepts, I see prayer and scripture with an eye for the experience being alluded to, for the practice being supported. The Eucharist is no longer a logic problem, the Gospels no longer problematic bits of history. There are a thousand ways to smack the floor; who can sing a hymn with an open heart and not feel a moment of contact with that one pure and clear thing?