Chris Bisignani

The Framework Game

ISSUE 16 | STUPIDITY | MAY 2012

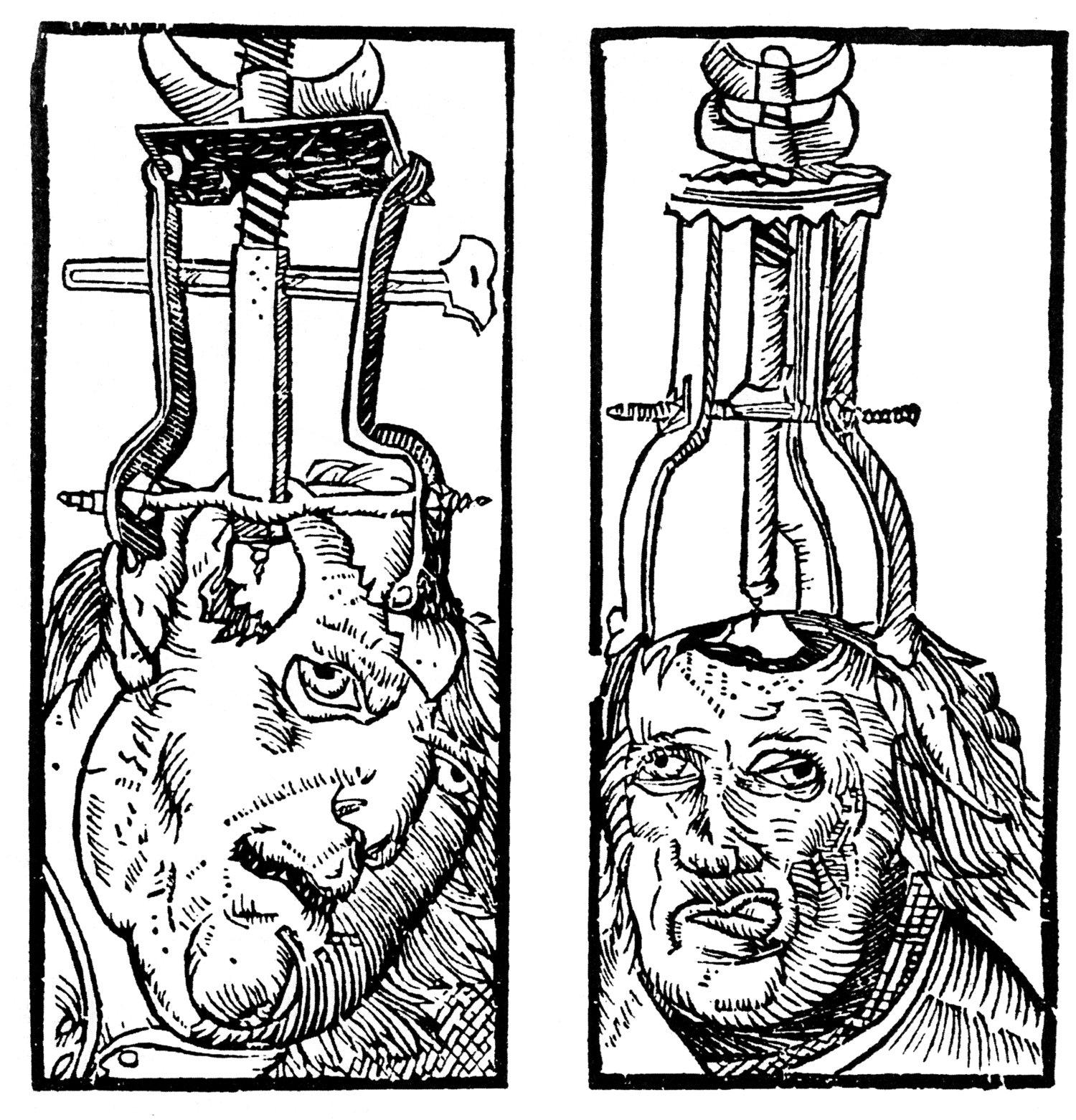

Peter Treveris, engraving of a trepanation, 1525

Gone,

gone,

gone over,

gone fully over.

Awakened!

So be it!—From the Prajñāpāramitā Hṛdaya

The Framework Framework (FF)

The ultimate framework for describing frameworks is: representation → transformation → interpretation. Some simple examples:

Cat and cat → 1 + 1 → 2 → 2 cats

Here, we can represent “a cat and another cat” as 1 + 1, transform this representation into 2 (a canonical form), and then interpret this result as “2 cats.”

Friend yelling at other friend → A yelling at B → A is angry at B → Friend is angry at other friend

In this case, we are representing our friends as archetypical people A and B. We then perform a simple deduction on their relationship (yelling), and interpret the resulting belief that “A is angry at B” from an abstract statement to a concrete belief about our friends.

More or less any mental procedure corresponds to a particular set of techniques for representing phenomena, performing transformations on the resulting representations, and then interpreting the result back into the world of the original phenomena. One goal of frameworks is reduction of complexity. After performing R → T → I on some data we hope to arrive at a simplified, but high-fidelity, form of the original. The result is information loss. In the case of the cats, we’ve lost the identity of the cats. In the case of our friends, our computed belief (anger) forgets the nuance of the yelling, the history of the yelling, the identity of the friends, etc.

The Framework Game

I was sitting in T. & J.’s apartment in Harlem when they started telling me about a new book that T. had been reading.1 The subject of the book was “slow thought” vs. “fast thought.” T. started explaining the basic concepts to me, and J. would occasionally chime in to fix details or offer further evidence of his claims. I began to feel that it was very Important to them that I Believe in Slow Thought vs. Fast Thought. At this point I realized that they were stuck in what I have started to refer to as “The Framework Game.” The Game more or less always takes the same form—a loose thinker constructs some basic semblance of a framework, backed up with “scientific evidence” and some carefully selected anecdotes; then, other loose thinkers start applying it to everything around them. See girl get horny translates into “fast thought!” Consider ultimate nature of frameworks becomes “slow thought!” In this case, T. had become convinced that all types of thinking are either “fast”—meaning that results/reactions are produced immediately, and that these reactions are produced based on the application of simple rules—or “slow”—meaning that conclusions are produced systematically, sometimes requiring an indeterminate amount of time. In the language of the Framework Framework (above), the book had provided T. with a representational scheme for the activities of the mind.

T.’s belief that all thinking falls into one category or the other means that he believed the scheme to be “total” on the domain of mind. The claim that a framework is total must necessarily be backed up with some sort of rhetorical or physical force.2 In the case of “slow thought” vs. “fast thought” the force took the form of endless examples which rendered me into such a state of stupor that I would have accepted more or less anything, just to make them stop. There were examples about advertisement and how it hijacks our “fast brain”, examples of experts and their hyper-accurate fast thoughts (a la Gladwell), examples about scientists and the differences between estimation (fast!) and experiment (slow!). I tried to argue with the framework—offering up the observation that there are plenty of fast algorithmic thoughts (e.g. while playing speed chess I will sometimes have a flash of new insight which requires the combination of lots of heterogeneous information) and slow perceptive thoughts (e.g. the creeping irritation I was feeling at having to listen to T. talk about this framework), but these arguments were brushed aside. T. claimed that the fast algorithmic thoughts were actually fast “slow” thoughts, and that the slow perceptive thoughts were slow “fast” thoughts—that the speed of the thoughts was not really crucial to their status as such.

The thing about the Framework Game is that once you’re stuck in it you don’t really have the capacity to see that you’re in it. Since the crux of the “Game” is the belief that a particular framework is total, any observation which could imply that it is not total is sucked up into a representation that the framework itself understands, is transformed, and interpreted into something that the framework has to say about it. This is often perverse. My arguments against “fast/slow-brain” were just “slow-brain arguments,” for instance. Why this mattered was not clear. The overwhelming feeling of the encounter was that, since T. was stuck in the framework, he was unable to evaluate statements about the framework, except in terms of the framework’s ontology.3

You know that someone is stuck in the framework game when they start making claims about “everything.” While doing research for this article I did a search for “everything is a” on Twitter and found these:

- Everything is a lesson in disguise.

- Everything is a decision.

- Everything is a plan created by the one who takes care of you in heaven.

- Everything is a process.

- Everything is a cliche.

- Everything is a lie.

- Everything is a miracle.

- Everything Is a Remix.

- Everything is a copy of a copy of a copy.

- Everything is a competition.

- Everything is a gastric activity.

- Everything is a dice roll.4

You can imagine the types of people who would believe these things, and the corresponding framework games in which they are trapped. One of the worst offenders, here, is “Everything Is A Remix.” I watched all 40 minutes of that schlock—have you seen it? It’s a big mashup of overblown rhetorical tricks whose aim is to establish its namesake conclusion. For example, at 0:45 in episode 3, the voiceover states (in all earnestness) “All artists spend their formative years producing derivative work.” ALL artists!? The obvious counter to the “remix” framework is the reductio ad absurdum: what is everything ultimately a remix OF, exactly? It can’t be remixes all the way down. The answer to this comes at 2:10 in the same episode: “These are all major advances, but they’re not original ideas so much as tipping points in a continuous line of invention by many different people.” These are the types of mental gymnastics loose thinkers take part in to maintain the totality of their frameworks—anything that doesn’t fit in the nice little model that the framework represents gets defined away by the representational scheme of the framework itself.

Now, you could claim that the “remix” framework isn’t really trying to be total—that it’s actually just saying that the vast majority of social forms are combinations of previously existing forms. But this is to miss the ultimately human character of the game. It’s the modern form of religion, really—the faith that allows people to live in a simple little world where everything is comfortable and fits into tidy boxes. Crossing the line between the obvious conclusion that 99.9% of stuff is a remix and the belief that exactly 100% of everything is a remix allows the carrier of this particular framework to engage in the following soothing behaviors:

- Assuring herself that even great thinkers like Einstein just combined the ideas of people before them—so why even try? Just sit back, relax, and combine. It’s all the same…

- Comforting herself that all one needs to do to accomplish anything is “copy, transform, and combine.” This allows her to overcome her obsession about the “meaning of life” and “making a difference.” This allows her to stop performing those other pesky nonsense behaviors like intuiting, filtering, memorizing, empathizing—anything that isn’t a replicative, transformational, or combinatorial action is simply an illusion that is there to keep you feeling weak and small.

Illustration by Tom Tian

It’s really sad when people get stuck in frameworks for too long. A classic example of this is when someone’s sense of humor becomes dependent on a canned response like “That’s what she said!” In epidemiological terms, the vector of infection in this case is some sort of systematic attachment to a television organism (show, channel, commercial, ...) which allows the organism to convince the host that its humor framework is a Good one—that other people like it—that women will like it—that it is ubiquitously recognizable and always funny. The host is primed for implantation by incessant repetition of the framework’s forms. Once he has been reduced to a sufficient state of stupor, transference occurs. At first, the host feels euphoria and freedom: other framework carriers recognize and appreciate the jokes the host is able to produce—the jokes are easy to craft—you can be funny without being clever or insightful! But eventually, as those around him move on to other frameworks, as his own taste begins to tell him that the jokes being produced are in fact boring, this euphoria morphs into tedium and finally outright terror. The two options at this point are either to drop the framework, leaving a festering hole where the host’s sense of humor once lived, or to continue drifting from framework to framework, ever more dependent on rigorous comical thought, moving into late-stage television dependency from which there is little hope of recovery. I know a lot of people who just reference South Park, instead of having a sense of humor. It feels as if they’ve lost their human aspect—even they don’t like their jokes. No one does. It is very sad.

I’ve been stuck in frameworks before. I used to be an Objectivist. Everything was “A implies A,” and “existence exists,” and “selfishness is a virtue” for a long time. The disease’s symptoms included compulsions to consort mainly with other objectivists, to fight against evil altruists on internet forums, to read all of Ayn Rand’s works over and over, to wonder why no one else Understood. What Objectivism gave me was a reassuring simplicity that allowed me to separate from the culture in which I was embedded.5 It was important for me, at the time, to believe that those around me were evil in precisely the ways that they thought themselves good. Oppressive religious grandfather becomes altruist zealot. Idiotic history teacher becomes “subjectivist.” Mean inaccessible hot girl becomes “philosophically impotent fool.” This is the real crux of the Framework Game. When we assume that a framework is total—that it is capable of completely representing the phenomena in a domain which we care about—then we are free to live in the fantasy world which it creates for us. The interactions between real things are represented as transformations on objects of an ontology which we believe in and deeply care about.

Escape

How do we get out of frameworks we’ve become stuck in? For escape I look to consciousness transformation. The point is to process, without conceptual framework. Through meditation, for example, we might find mental space and time to gain perspective on our over-attachment to frameworks. Through “Great Faith, Great Courage, and Great Doubt”6 we can find the power to transcend them. Through psychedelic drugs we attain an egoless state in which frameworks lose their weight. By delving into nature we return to our original selves and our frameworks appear as mere tools of humanity.

My point isn’t that frameworks are bad, though. They’re powerful and useful and interesting. I love math, for instance! It’s just boring when you’re caught in them, is all. It’s important to have tools of awareness and escape at your disposal. Hopefully reading this has helped you gain perspective on frameworks you might be stuck in.7

1 I assume the book T. had been reading was Thinking, Fast and Slow, by David Kahneman. I haven’t read the book. My rendering of the conversation involving T. and J. is meant to convey my understanding of their relationship to the ideas of the book, not the content of the book itself. However, a quick survey of the first pages of the book suggests that it does, in fact, attempt to convey the idea that Fast Thought/Slow Thought (System 1/System 2 in its vernacular) constitutes a total representational space for the activities of mind.

2 Unless it actually is total—e.g. Solipsism is arguably a total framework—corresponding to representing everything as nothing—but is anyone ever really a Solipsist?

3 Here, I’m using “ontology” to mean the set of all possible representations available to the framework. The ontology of a simple arithmetic framework would be the natural numbers and relations on those numbers (addition, multiplication, subtraction). The ontology of T.’s framework was “fast thought,” “slow thought,” the systems underlying these “the fast/slow brains.”

4 • (Not Everything is a Good Acronym. NEGA.)

5 Bigoted religious family—Wilmington, DE, c. 2000.

6 Sutra 14 of “The Mirror of Zen”—Three things are essential in Zen meditation. The first is Great Faith. The second is Great Courage. The third is Great Doubt. If any one of these is missing, it becomes like a tripod cauldron that is missing on leg—it is of no use at all.

7 But make sure you don’t get stuck in the “don’t get stuck in frameworks” framework!