Sarah Ackley

Picturing Abortion

ISSUE 14 | INNOCENCE | MAR 2012

Lennart Nilsson, from A Child Is Born, 1965

The stunning fetal images by photographer Lennart Nilsson, first published in the April 3, 1965 issue of Life, have become iconic in the anti-abortion movement. According to Life Site News, Nilsson is credited with taking “photographs that the pro-life movement has found priceless: the earliest and most compelling visual images that give intimate detail and clarity to the humanity of unborn children in the womb.” Rev. Thomas Euteneuer, President of Human Life International, an anti-abortion advocacy organization, has said, “Images such as those created by Lennart Nilsson absolutely reaffirm the humanity of unborn persons, which is why they are so unpopular with pro-abortion forces.”

Nilsson certainly wasn’t the first to photograph the fetus. A number of photographs of embryos and fetuses appeared in the July 3, 1950 issue of Life magazine, but Nilsson was thought to be the first to photograph live fetuses in the uterus. The editor’s note of the 1965 issue of Life reads,

The opening picture in Nilsson's essay, a live baby inside the womb, is a historic and extraordinary photographic achievement... [A] doctor said, “As far as I know, in utero pictures such as Nilsson's have never been taken before. When you take living tissue in its living state and view it in its natural surroundings you can see things you can't see afterward. Being able to view the fetus inside the uterus, and being able to note its circulatory details, is rather sensational from our point of view.”

Perhaps Nilsson’s most famous image, which did not appear in the 1965 issue of Life, but did appear in his 1965 book A Child is Born, is of a 20-week old fetus sucking its thumb. This particular image has appeared on “Choose Life” posters at anti-abortion rallies over the years, marshaled as evidence of the full humanity of fetuses. However, Nilsson’s famous photos were not of live fetuses in the uterus, but instead of abortus material. In fact, the use of dead embryos “allowed Nilsson to experiment with lighting, background and positions, such as placing the thumb in the fetus’ mouth.”

In the last few decades the anti-abortion movement has increasingly fought the abortion debate with images such as Nilsson’s. Enlarged photographs of dead fetuses—or even fetuses preserved in jars—have long been mainstays at anti-abortion rallies, but the use of fetal images expanded rapidly with the growing use of ultrasound imaging in the ’70s and ’80s and the rise of the Christian Right in the ’80s. In 1983, an article titled “Maternal Bonding in Early Fetal Ultrasound Examinations” published in the New England Journal of Medicine told the story of two women who decided against abortions after seeing ultrasounds of their fetuses. The authors presciently wonder: “Could ultrasound become a weapon in the moral struggle?” In fact, these authors are credited in part with inspiring The Silent Scream, the 1984 anti-abortion film depicting via ultrasound an abortion in real-time. In her 1987 essay, “The Power of Visual Culture in the Politics of Reproduction,” political scientist Rosalind Pollack Petchesky wrote: “Aware of cultural trends, the current leadership of the antiabortion movement has made a conscious strategic shift from religious discourses and authorities to medicotechnical ones, in its effort to win over the courts, the legislatures, and popular hearts and minds.”

The power of images, fetal and otherwise, lies in their ability to communicate simple concepts, but such communication can also divorce them from their complex, real-life context. The abortion-rights movement, objecting to the weight the fetus carries in the debate, has instead attempted to contextualize abortion, often by telling the stories of real women facing unintended pregnancies. For the most part, abortion-rights activists have eschewed the use of imagery, ceding the power of the “visual terrain” to anti-abortion advocates.

Michael Clancy’s Famous Image

To understand the difficulties abortion-rights advocates face in using visual imagery, we must first understand how the anti-abortion movement has made effective use of imagery and how this imagery is at times lacking crucial context. In 1999, Michael Clancy, a photographer and recent convert to Christianity, was invited to take photos of a 21-week old fetus undergoing surgery to correct spina bifida, a congenital disorder. Clancy agreed to take the assignment, and later described it as “a slap in the face and a clear calling for a mission.” During the surgery, according to Clancy, the fetus reached out of the uterus and grabbed the doctor’s finger and held on tightly:

A doctor asked me what speed of film I was using, out of the corner of my eye I saw the uterus shake, but no one’s hands were near it. It was shaking from within. Suddenly, an entire arm thrust out of the opening, then pulled back until just a little hand was showing. The doctor reached over and lifted the hand, which reacted and squeezed the doctor’s finger. As if testing for strength, the doctor shook the tiny fist. Samuel held firm. I took the picture! Wow! It happened so fast that the nurse standing next to me asked, “What happened?” “The child reached out,” I said. “Oh. They do that all the time,” she responded.

Clancy’s photo was published on September 7, 1999 in USA Today, which stated that the fetus reached out on its own and grabbed the surgeon’s finger. Clancy’s photo has been immensely popular with the anti-abortion movement; one anti-abortion website states: “[Clancy’s photograph] should be ‘The Picture of the Year,’ or perhaps, ‘Picture of the Decade.’ ...There is now no question that it is a living, growing, feeling human being long before birth.”

However, the surgeon’s story doesn’t match up with Clancy’s. The surgeon, Joseph Bruner, in an article published on May 2, 2000 in USA Today, stated, “The baby did not reach out. The baby was anesthetized. The baby was not aware of what was going on.” Bruner’s comments effectively ended Clancy’s career as a photojournalist. Clancy continues to defend the authenticity of the image: “I will dedicate my life defending this photo... This is God’s picture.” Despite this controversy, according to a Fox News report, the photograph was nonetheless cited during Congressional debates over the Partial Birth Abortion Ban Act, which was later passed in 2003.

The Response of the Abortion-Rights Movement

The abortion-rights movement has generally taken two approaches to combating the anti-abortion movement’s position that fetuses are persons. First, they object to the very proliferation of fetal imagery, often seeing it as propaganda that has changed the landscape of the abortion debate by endowing the fetus with personhood. Second, they attempt to contextualize abortion both in order to divert attention from the fetus and reframe the argument in terms they find more meaningful.

I. Defeating the “Fetus Fetish”

Not every abortion-rights advocate objects to the growing use of fetal imagery. Feminist author and abortion-rights supporter Naomi Wolf writes: “While images of violent fetal death work magnificently for pro-lifers as political polemic, the pictures are not polemical in themselves: they are biological facts. We know this.” However, there are a number of abortion-rights supporters who would disagree with Wolf. They object to fetal imagery not only because of obvious distortions, but because they see nearly all fetal imagery as subtly manipulative in that it removes the pregnant woman and the biological dependence of the fetus on her from the picture. Petchesky writes, “In fact, every image of a fetus we are shown, including The Silent Scream, is viewed from the standpoint neither of the fetus nor of the pregnant woman but of the camera. The fetus as we know it is a fetish.” A fetish is not simply a topic of interest, but a fantasy, divorced from reality, that takes on meanings of its own. Petchesky continues,

[T]he fetus is not only ‘already a baby,’ but more a ‘baby man,’ an autonomous, atomized mini-space hero. This image has not supplanted the one of the fetus as a tiny, helpless, suffering creature but rather merged with it (in a way that uncomfortably reminds one of another famous immortal baby).

Many abortion-rights advocates see fetishizing as dangerous in that it cuts off any opportunity for dialogue on competing values in a pluralistic society; if they can make the case that the fetus is of irrational or obsessive importance to anti-abortion advocates, then they can potentially reframe the debate, diverting attention on both sides from the currently salient question, “Are fetuses persons?” (Or, alternately phrased, “Are fetuses morally equivalent to a piece of dandruff?”)

Slogans such as “Defeat the fetus fetish” have appeared at abortion-rights movement rallies. Petchesky’s article too represents a critique of fetal imagery, though with a limited audience through the subscription-only, academic publication Feminist Studies. Others have also written about fetal imagery and fetishizing, usually also with an academic tone.

Perhaps because the concept of a fetish is rather academic, critiques have fallen on somewhat deaf ears. (Do even those who carry “Defeat the fetus fetish” signs necessarily understand its meaning?) In an article titled “Bringing Science Back to the Abortion Debate: Helping Women, Unborn Children” appearing in Profile News, the authors fail to respond meaningfully to the concept of fetishizing:

According to conventional wisdom, anti-abortion advocates are vulnerable to charges of being anti-woman and anti-science. Pro-lifers subordinate dispassionate scientific inquiry to irrational religious belief, many people believe, and their "fetus fetish" blinds them to the plight of women in crisis pregnancies. But two novel laws passed recently in Nebraska explode those myths by highlighting how pro-lifers have embraced women and seized the mantle of science by revealing exactly what it is those who abort are choosing.... Ultrasound images give mothers and fathers an enhanced picture of what—of who—is being destroyed in an abortion. Twenty states have laws that allow women considering abortion to be offered a chance to view an ultrasound image of their unborn child.

As Petchesky argues, the “mantle of science” does not preclude fetishizing; in fact, medical science encourages it: ultrasound technologies have not only allowed us to view the fetus as if independent of the pregnant woman, but they have made such a viewing compulsory, a necessary procedure for the health of both woman and fetus.

Blog comments, such as the following, also indicate that the idea of a fetish as fantasy is often lost on people: “you pro aborts like to say that we pro lifers have a fetus fetish i must conclude that you pro deathers have a fetus fetish also……just as long as they are dead. do you also have a suction machine fetish since you love abortion so? and all that rap about abortion clinic bombing…a bomb fetish?” The commenter fails to realize that it is for the anti-abortion movement, and not the abortion-rights movement, that the grotesque images of dead fetuses have come to take on symbolic meanings. For the anti-abortion movement, abortion, as symbolized by the dead fetus, has come to symbolize a “culture of death” in which humans are treated as consumer products. A recent anti-abortion piece titled “Obama’s Culture of Death” in the Washington Times expands upon some of the meanings of abortion:

Abortion is liberalism’s genocide. Since Roe v. Wade, nearly 50 million babies have been killed—lives exterminated in the womb of their mothers. Abortion clinics are the Gulag Archipelago of the modern left—a vast system of death camps underpinning the liberal regime’s secular hedonism. For a godless society predicated upon consequence-free sex, pregnancy is an unwanted nuisance—and a barrier—that must be eliminated. If lives are destroyed, then that is the price of sexual utopia. This is why liberals adamantly refuse to defund Planned Parenthood. And it is why Mr. Obama staunchly supports the government financing of abortion services: It encodes the pernicious principle that an entire category of people—the unborn—are less than fully human and therefore can be arbitrarily extinguished.

In this broader context, objecting to fetal imagery is difficult, since the entire debate over abortion has taken on numerous symbolic meanings tied up in broader conflict and ideological differences between the Christian Right and the Left.

II. Contextualizing Abortion

The second way that abortion-rights activists respond to fetal imagery is by attempting to divert attention from the fetus to the pregnant woman (and others) by contextualizing the fetus both medically and socially: the fetus exists within the uterus of a real woman and not as a lone “Spaceman Embryo,” and abortion exists in the broader context of a society which offers imperfect sex education and access to contraception and is fraught with violence and poverty.

However, contextualizing pregnancy and abortion is no easy task. Once a fetus is established as a person, we are easily convinced it is deserving of our sympathy; it is innocent, dependent, and incapable of making mistakes or behaving immorally or recklessly. In contrast, when we tell stories of unintended pregnancies, the pregnant woman is often put on trial. She is almost certainly not innocent, and probably deserving of only qualified sympathy; we can contextualize pregnancy within the framework of the woman’s economic and health needs, relationships, and desires, but, once we have done so, there is no guarantee that we will agree on how she should have acted or should presently act.

The controversy surrounding the death of Becky Bell in 1988 illustrates this concept. Bell was 17 when she got pregnant. As the state of Indiana required parental consent for minors seeking abortions and Bell was not comfortable telling her parents, she sought an illegal abortion. As a result, she died of a massive infection a week later. Abortion-rights advocates publicized Bell’s case and pointed out that she would not have died had parental consent laws not prevented her from seeking a safe, legal abortion. Anti-abortion advocates responded first by disputing whether she in fact died from an illegal abortion at all—perhaps she died from fast-acting pneumonia, they suggested. Then they brought to light her alleged illegal drug use and so-called promiscuity. Her drug use may have been somewhat relevant, as there were theories that her alleged drug use may have caused her to miscarry. These theories are medically dubious, though, as Bell did not test positive for any drugs and it is debatable whether marijuana, the one drug she was not tested for, causes miscarriages. Without a doubt, though, she was branded as promiscuous purely to tarnish her character, to make her less deserving of our sympathy. The discussion surrounding her death became less about parental consent laws and their effects, positive or negative, on minors seeking abortions, and more about whether or not Bell, in some sense, deserved her fate.

The Death of Gerri Santoro

While abortion-rights advocates have not for the most part relied on imagery to make their case, there are a few notable exceptions which illustrate some of the difficulties they face in making effective use of pictures. One such abortion-rights image is that of Gerri Santoro’s dead body. In April of 1973, Ms. Magazine, in an article titled Never Again: Death, Politics and Abortion, published an image of a nameless woman who had died from an illegal abortion in 1963:

This woman was the victim of a criminal abortion. Her body was photographed exactly as it was found by police in a bloody and barren motel room; exactly as it had been abandoned there by an unskilled abortionist. Becoming frightened when “something went wrong,” he left her to die alone.

The photograph is just one bit of evidence in the files of the Connecticut medical examiner who determined the technical cause of her death: an air embolism resulting from the unskilled surgical procedure. But this visible evidence of butchery has come to symbolize far more than an individual case with an individual cause.

Because various abortion-law repeal and reform groups have used this photograph as one answer to the magnified fetus photographs so often displayed by antiabortion forces, this individual woman has come to represent the thousands of women who have been maimed or murdered by a society that denied them safe and legal abortions.

But like Nilsson’s thumb-sucking image, this abortion-rights image too lacks important context, as anti-abortion activists are eager to point out. The woman in the photo was later identified by her sister. Prior to her death in 1963, Santoro left her abusive husband and moved to Connecticut with her two daughters. She began an affair with a married man, Clyde Dixon, and became pregnant. At 6 ½ months pregnant, she learned that her husband was coming to visit her and her two daughters. Fearing for her safety if her husband discovered her pregnancy, she and Dixon checked into a hotel and attempted to perform a third-trimester abortion using borrowed surgical instruments and a textbook. When Santoro began to hemorrhage, Dixon left, leaving her to die alone. Dixon was apprehended by the police three days later and charged with manslaughter.

Even in states with the most liberal abortion laws, there is nothing to prevent Santoro’s situation from happening again. Abortion, in the US, is not legal past the point when the fetus could survive on its own, except in cases where the woman’s health is in jeopardy. Furthermore, the legality of third-trimester abortions in cases of health is no guarantee of quick access. There are very few clinics in the US which offer third-trimester abortions and women often have to travel great distances for these late-term abortions. “Never Again,” the slogan often attached to Santoro’s image at abortion-rights movement rallies, seems not quite to apply to her particular situation. Santoro’s image, like Nilsson’s pictures of dead fetuses, has come to symbolize something incompatible with its original context.

Santoro’s image has been somewhat powerful in the abortion-rights movement by offering a disturbing reminder that women with limited options due to the illegality (or inaccessibility) of abortion sometimes attempt to end their pregnancies in ways that are detrimental to their health and potentially fatal. Even today, more than 40 years after its original political use, her image still occasionally appears on abortion-rights posters. However, Santoro’s image in many ways isn’t a positive one for the abortion-rights movement. It portrays women as victims of circumstance, much in the same way that anti-abortion advocates portray women as victims of the “pro-abortion agenda.” The narration of The Silent Scream puts it this way:

In discussing abortion we must also understand that the unborn child is not the only victim. Women themselves are victims, just as the unborn children are. Women have not been told the true nature of the unborn child. They have not been shown the true facts of what an abortion truly is. Women in increasing numbers—hundreds, thousands, and even tens of thousands—have had their wombs perforated, infected, destroyed. Women have been sterilized, castrated, all as a result which they have had no true knowledge. This film and other films which may follow like it, must be a part of the informed consent for any woman before she submits herself to a procedure of this sort.

Furthermore, images like Santoro’s are somewhat antithetical to the way that the abortion-rights movement has framed itself politically (hence the term pro-choice). The abortion-rights movement wants to combat anti-feminist notions like those in The Silent Scream that women are often manipulable, naive, and incapable of making complex decisions. The abortion-rights movement is attempting to communicate two concepts that in their simplest form may appear antithetical: abortion should be legal both because women are too often the victims of circumstance and because women are capable of autonomously making decisions. Abortion-rights advocates want to recognize at the same time that women in our society face difficult circumstances—violence and economic and medical hardship—that make carrying unwanted pregnancies to term difficult or impossible, but also that in the face of such hardship women are capable, at least most of the time, of weighing the pros and cons of an abortion and making an ethical and informed decision.

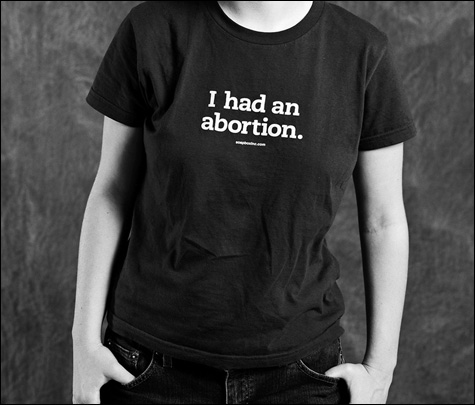

“I Had an Abortion”

Since there is no single image that can convey both autonomy and desperation, the other visual strategy employed by the abortion-rights movement is to make abortion, like the fetus, a public presence. Forty percent of American women have had an abortion. (Abortion rates have been decreasing since the ’80s, however, so based on current rates this number will be closer to 30% in the future). The logic is that if we could somehow see these numbers, as well as understand the stories behind them, the abortion debate might, instead of focusing on questions of fetal personhood, have to contend with the fact that abortion is an extremely common medical procedure, as well as with the diverse and complex experiences of women facing unintended pregnancy.

The “I Had an Abortion” project aims to do just this—to make visible women who have had abortions. Jennifer Baumgardner started the project in 2003 by selling t-shirts that read “I Had an Abortion,” partially with the intent that women would wear them to the 2004 abortion-rights March for Women’s Lives in Washington, DC. The project later evolved into a film, a book, and a photography exhibition, which document the abortion experiences of 11 women, some of whom are otherwise famous. The photographs in the exhibition feature a diverse set of women by themselves or posed next to their partners or children wearing the “I Had an Abortion” T-shirt. The images communicate a sense of independence and peace with the decision to have an abortion—these photographs are not of women who regret being manipulated into an “unethical decision.” While these images do not in themselves convey desperation or the hardship some of these women faced when deciding whether or not to end their pregnancies, their stories do. This may represent the most holistic and positive visual representation of abortion.

However, it’s worth noting as well that members of the anti-abortion movement are just as capable as those of the abortions-rights movement in engaging in the realm of narrative. They too show images and tell the stories of women who have had abortions, but instead of looking powerful, these women look sad or pensive and talk about how they regret their reckless, immoral behavior and “killing their baby” and how they were manipulated into doing so by self-interested boyfriends and misinformation. Silent No More, an anti-abortion advocacy group, makes posters for rallies reading “I regret my abortion” and “I regret lost fatherhood.” Making abortion a public presence has become a goal for some in both the abortion-rights and anti-abortion movements, but with differing tones and contexts.

The Future of the Fetal Imagery: New Challenges for Abortion Rights Advocates

Given the importance of imagery to the anti-abortion movement in telling its “story” and the comparatively limited success that abortion-rights advocates have had in its use, one might ask what the visual terrain of the abortion debate might look like in the future. The answer may well not be encouraging for abortion-rights advocates.

The effects of the proliferation of such fetal imagery and the corresponding questions of fetal personhood reach beyond just the abortion debate into other arenas of reproductive health. If the fetus is a person with rights, then the right not to be aborted is just one of these rights. There have already been court-ordered Cesarean sections, with opposing lawyers representing fetus and mother-to-be in court. New reproductive technologies, such as 4D ultrasound and fetal surgery, pose new questions. Will the use of these technologies become increasingly compulsory? Might there one day be court-ordered fetal surgeries? These questions, while certainly on the horizon, are not, for the time being, pressing: fetal surgery is preliminary and risky, and 3D and 4D ultrasound are not thought to confer benefits which outweigh the risks in most cases (although an increasing number of hospitals offer them).

Meanwhile, few examples exist of imagery that resonates with the abortion-rights message, yet the anti-abortion messaging continues to grow in impact: fetal imaging technology has improved in quality and is broadly available and increasingly requested by doctor and patient alike (as much to celebrate family milestones as to detect medical abnormalities). With consumer pressures in place, the anti-abortion movement can, with little effort, marshall such images as evidence of fetal personhood. With no comparably powerful set of imagery at its disposal thus far, the abortion-rights movement will likely remain on the defensive with respect to questions of fetal personhood.