Eliot D’Silva

“An illustration changes us”: Images of Innocence in John Ashbery

ISSUE 14 | INNOCENCE | MAR 2012

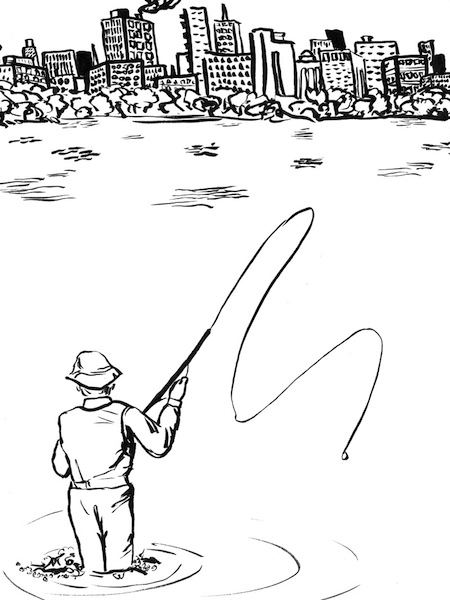

Illustration by Naomi Bardoff

In the middle of his prose poem “Meditations in an Emergency,” Frank O’Hara writes:

However, I have never clogged myself with the praises of pastoral life, nor with nostalgia for an innocent past of perverted acts in pastures… —I can’t even enjoy a blade of grass unless I know there’s a subway handy or a record store or some other sign that people do not totally regret life.

Against O’Hara’s cool dismissal of the countryside, in this essay I want to suggest how John Ashbery’s poetry constitutes proof that the pastoral need not cause people to “totally regret life.” For Ashbery, melancholy and tinges of regret can act as signs of a more complete mimesis, amounting to something greater than a life submitted to what is “handy” or enjoyable. Moreover, in his version of pastoral, Ashbery resists the standard alternatives for interpreting and attributing value to our innocent pasts. Through repeated reference to agrarian and domestic settings, he puts pressure on our assumptions and denials of substantial, continuing identities that spring from childhood. Always holding off the pull of time, Ashbery’s writing is one in which:

The past is yours, to keep invisible if you wish

But also to make absurd elaborations with

And in this way prolong your dance of non-discovery

In brittle, useless architecture that is nevertheless

The map of your desires […]

These lines from Ashbery’s poem “Clepsydra” depict a characteristically ambitious movement back not to the real past but to a built past, a “brittle, useless architecture” that appears comical yet nevertheless constitutes a “map” or pathway towards what the poem calls “that sphere of pure wisdom and / Entertainment”. This form of poetic license affords Ashbery’s speakers an endless fluidity of expression deeply at odds with William Empson’s observation, in his classic study Some Versions of Pastoral (1935), of the

feeling that life is essentially inadequate to the human spirit, and yet that a good life must avoid saying so, is naturally at home with most versions of pastoral; in pastoral you take a limited life and pretend it is the full and normal one.

Faced by the volubility of Ashbery’s later work, this definition is going to have trouble, particularly with “The Burden of the Park” (1998). It is a funny and collagic piece that exemplifies the way poetry can become a mode of living within the whole gamut of social roles provided by rivers, parks, and suburban homes. Of all the voices that fill and fracture that poem, Ashbery saves his most parodic tone for the fisherman who enters midway through the following section:

We once made

some mistake, it seems, and now we are to be judged, except

it isn’t so bad, someone tells me you’ll be let off the hook,

we will all be able to go home, sojourn and smile again, be racked

with insidious giggles like guilt. Meantime, jugglers swarm over

the volcano’s

stiff sides. We believe it to be Land’s End, that it’s

six o’clock, and the razor fish have gone home.

Once, on Mannahatta’s bleak shore,

I trolled for spunkfish, but caught naught, nothing save

A rubber plunger or two. It was awful,

[…]

The period of my rest is ended.

I shall negotiate the fall, and then go crying

back to you all. In those years peace came and went, our father’s

car changed

with the seasons, all around us was fighting and the excitement

of spring.

Not only does “Manahatta’s bleak shore” mark out an urban territory from which the voice is dislocated, it also sets up an allusion to the final stanza of T.S. Eliot’s The Waste Land where a beached speaker sits “Fishing, with the arid plain behind me.” Something of this intertextual focus also informs the poem’s title, which recycles W. Jackson Bate’s 1969 book The Burden of The Past—a discussion of literary modernism—with its own chatty, pastoral decorations. Against the anguished and dissatisfied mentalities of Eliot and Bate, who believed culture had fallen into desiccation, we can see the value of Ashbery’s approach, with its enthusiasm for traditions and interest in how they might be transformed. Indeed, Ashbery wants less to be clogged by nostalgia than to actively adjust our conceptions of the past: he comes across like a prankster, restocking the most familiar narratives with new images such as that of the jugglers who “swarm over / the volcano’s / stiff sides.” Empson’s decision to frame the pastoral in jaded terms, as presenting “a limited life and pretending it is a full and normal one,” cannot account for this abnormal vision not of a limited life but of the impossibility to contain liveliness, mimed formally by several rapid enjambments. More generally, the poem refers to the Edenic fall from innocence (“We once made / some mistake”) but this kind of transgression becomes as reversible as the meaning of the verb “racked” which flickers, across the line-ending, from a suggestion of torture to a childish fit of “insidious giggles.” Jejune in its carefully staged distress, the verse never quite loses its foothold but “negotiates the fall”, settling back into the first person voice and transporting us to a scene of youthful domesticity where “all around us was fighting and the excitement / of spring.”

Domestic life spent around the home appears frequently as a trope in Ashbery’s work. Positioned between the odd blankness of a busy metropolis—what the poet has described as “a logarithm / Of other cities”—and the artificial solace of purely rural areas, the house figures a place where childhood identity can be exhumed and given the correct conditions under which to flourish. Inside the house, images of the self can enter together in ways that make the transition from past to present both more significant and more negotiable. Later in “Clepsydra,” for instance, there is a sudden turn inward:

Purpose can blaze unexpectedly in the acute

Angles of rooms. What is meant is that this distant

Image of you, the way you really are, is the test

Of how you see yourself, and regardless of whether or not

You hesitate, it may be assumed that you have won, that this

Wooden and external representation

Returns the full echo of what you meant

Perspective has telescoped from the impersonal “architecture” mentioned above to “rooms” and the “wooden external representation” which, in the process of reifying the self, brings an awareness of all its contingent personalities. In its dealing with the space between self and world, this passage might also recall Elizabeth Bishop’s cry in “Crusoe in England” of “Home-made, home-made! But aren’t we all?” Thus, in “The Logistics”, a more recent poem from Planisphere (2009), Ashbery equivocates:

Then tomorrow? Then tomorrow.

We’ll travel; the day

will be a scorcher. Some say.

Travel beyond the rocks

to a taped place

some will recognize,

others not so much,

some not at all—

what place is this?

Although the halting syntax and muted tone put us on shaky ground, in the mention of “a taped place” there is a kernel that lionizes the whole enterprise. “Taped” seeks to observe both the way places are patched together and also to register how the medium of poetry commits matter to memory through a process of recording (Ashbery is known to have walked the streets of New York with a dictaphone in his early twenties.) Much of Ashbery’s work has concerned itself with versions of this taped place and the epistemological states they permit. Just like looking at ourselves through worn scrapbooks or on VCR footage, there is sadness in seeing our attachments to previous moments exposed as durable but inadequate. Nowhere are these tensions more playfully on display than in Girls On The Run (1999), a book-length poem that takes its title from a set of paintings and collages by Henry Darger. In Darger’s artwork dozens of stray phenomena, from candy wrappers to newspaper cutouts, are taped back into being, creating a childish world, busy with mischief and incident. However, in Ashbery’s poem, emphasis is laid on the seams at which the fabric of youth might come apart: his project is, conversely, to deconstruct and put back together the old moments he has selected from Darger’s material. Or to quote from the prose work Three Poems (1972), for Ashbery “The phenomena have not changed. But a new way of being seen convinces them they have.” Section VII of Girls On The Run shows truth permuting in exactly this way:

Sometimes they were in sordid sexual situations;

at others, a smidgen of fun would intrude on our day

which exists to be intruded on, anyway.

Its value, to us, is incommensurate

with, let’s say, the concept of duration, which kills,

surely as a serpent hiding behind a stump.

Our phrase book began to feel useless—for once

You have learned a language, what is there to do but forget it?

An illustration changes us.

As the casual qualification of the third line makes clear, space opens up so that different activities can mingle to outpace the “serpent hiding behind a stump,” introduced as an obvious mascot for the fall from grace. Yet I would stress that freedom from duration cannot but give way to something thornier, since even the “smidgen of fun” is chastened by the demands of communication. The stanza ends on a note of Wittgensteinian disenchantment, aware that the primitive “phrase book” cannot prepare us for the entailments of the social practices in which its words are used. It is “an illustration” that holds sway, and innocence must be lost in the sticky process of learning by example rather than rule.

By opening his art up to thought experiments of this kind, Ashbery directs attention less towards O’Hara’s concrete sense of “acts in pastures” than to abstraction and the obscure quality historical moments. Like the persona in “West Casements”—for whom retrospection becomes a drifting back “toward a surface that can only be approached, / Never pierced through into the timeless energy of a present”—the reader’s experience is punctuated by sudden gaps and vagueness. The capaciousness of Ashbery’s sense of time and space means that human situations become more engaging in their imaginative reach than their actual enactment. Consider this occasion in Section XIV:

The effect was startling; moths buzzed in the light

from its extraordinary vibrations. Fifteen years passed this way.

When it was over no one had the courage to come out into the daylight,

or knew there was any. I fell asleep

on a sandhill, and dreamed this, and gave it to you, and you thanked me,

solemnly,

but we were not permitted to associate, only to correspond, and you came

out

to me again, and we wished one another good afternoon, and then went

away

again into the fog-lit embrasure. Not that we didn’t have good reason

to do whatever we did, but the question never came up again.

Where was I? Back in the explorer’s cottage, with the thundering sea

Out of the haze of hermetic pleasure established in the first few lines, a relationship flowers briefly before the pained admission “but we were not permitted to associate, only to correspond.” Normally, to correspond might sound more intimate than to associate but I think in this poem’s context it is to be taken as connoting an epistolary distance not unlike that presented in the previous section, where a remote voice can be heard saying: “I’ll write you from that solemn coast / but you must promise never to remember me, never speak of me / until we are found at last behind the bathroom door with the broom.” No matter how surreal or teasing that last image might seem, its insistence on crossing the bathroom’s boundary is in keeping with both the spatial and sexual aspects of “you came out / to me,” especially as the term “embrasure” means an opening in a thick wall for a door or window. These are fragile, yearning exchanges but ones that cannot last. Pathos is soon flattened out by the throwaway tone of “whatever we did” instead of “what” that readers are likely to expect, and then deflated entirely when “but the question never came up again” is followed with a question in the next clause. “Where was I?” Ashbery seems to ask himself, as he reverts to the bizarre imagery of the final line—affect fluctuates between longing and amusement and a precious feeling gets caught up in the flux of the poem’s form.

This long poem moves, then, in a meandering fashion that keeps the titular girls and their innocence beyond the grasp of any one readerly tactic. However, after the vacancy of his enquiries into the whereabouts of Mary Ann and Jimmy and “who knows what advises them, / discreet in the mayhem,” Ashbery shifts registers with athletic pace, leaving the reader some of the most limber thinking in the book:

Yet who knows what advises them,

discreet in the mayhem? And then it’s bright in the defining pallor of their

day.

Does this clinch anything? We were cautioned once, told not to venture

out—

yet I’d offer this much, this leaf, to thee.

Somewhere, darkness churns and answers are riveting,

taking on a fresh look, a twist. A carousel is burning.

The wide avenue smiles.