Andy Jordan

Brain Wrap

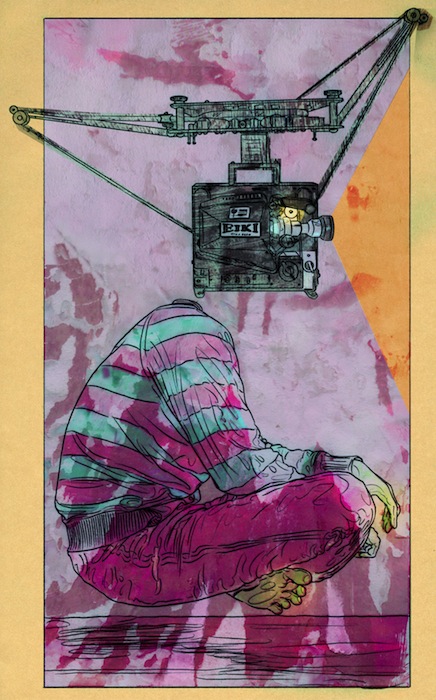

ISSUE 11 | BEHIND THE CAMERA | DEC 2011

Illustration by Wesley Ryan Clapp

In the projectionist’s booth, it’s easy to lose track of time, but losing track of time is the worst mistake you could make. People won’t really mind if the floors are sticky or the popcorn is stale, but there’s a movie starting every five minutes, and God help the projectionist who starts it five seconds late. So try to ignore the sound of the film as it clicks and whirrs through the projector, each frame passing for a single, measured moment before the light of the plate and the eyes of the audience. Close your ears to the basso hum of the bulb. Like a mechanical lullaby, an impossibly rhythmic ocean, the even click of the film and the calibrated hum of the bulbs can lull you to sleep. Or, if not to sleep, into a lazy stupor: eyes filled with colors dancing on the screen below, ears filled with the mechanical click-click-click-click of the sprockets at their work.

The first time Matt explains the sprockets to me, it just seems like showing off. He reels off the list faster than a frame can move through the projector: “Digital soundhead, upper sprocket, plate, intermittent sprocket, lower sprocket, analog soundhead, bottom sprocket, failsafe.” Each sprocket is just a fat steel cylinder with teeth for grabbing perforations on the edge of the film stock. When the projector runs, the sprockets spin and pull the film through at a constant rate. Matt shows me how to “thread” the labyrinth of sprockets and spools, how to frame the film over the plate, how to give slack after the upper sprocket and before the lower sprocket, how to spin the flywheel and work the intermittent sprocket, how to engage the failsafe, and how to wipe the oil off my hands after I’m finished.

Matt also shows me how to work the platter system. Forget everything about film being stored in upright reels, the classic two-humped silhouette of the old-school projector. In the modern multiplex, film is stored off to the side of the projector on horizontal platters. This saves theaters time by eliminating the hassle of rewinding. A basic reel-to-reel system can only move film from the outside of one reel to the inside of another, reversing its order in the process. In a platter system, film is pulled up from the inside of one platter, run through the projector, and collected on the inside of another platter, ready to be shown again. Of course, every solution carries along its own problems, and the problem with spooling film from the inside can be best illustrated by wrapping a string around your finger, then yanking on it. Instead of unwrapping neatly, the coils of string just get pulled tighter around the center. Similarly, a projector’s endless hunger for film can pull the reel into thousands of tight, black ringlets. If these twists ever enter the projector, you have a gigantic mess on your hands.

The machine responsible for preventing this disaster is called the brain, a squat cylinder that sits at the center of the sending platter. Film moves from the inside of the reel, through the brain, and out to the projector. When the brain’s arm is up, the projector pulls film as normal, but now the film coils around the brain instead of around itself. When the tension from this wrap builds up, it pulls the brain-arm down, telling the platter to rotate in reverse and unwrap the excess film. The brain can malfunction in many ways, but the most common is called a “brain wrap.” This happens when the brain fails to sense the tension building up around it and allows the film to wrap forever. Friction builds up and the rate of film going to the projector slows, or tries to slow. Projectors must take in film at a rate of 24 frames per second, and they will bring the entire booth crashing down around them before accepting anything slower. The film may slow down, but the sprockets keep their own time, and their teeth will shred any film that resists. Usually, the film just breaks, but sometimes, Matt tells me, the friction can build up so high that it burns instead.

I’m in the booth with Matt learning how to run the projectors because soon, our theater won’t have any projectors to speak of. That is, we’re in the process of going digital. Nearly half of our screens are already running on digital projectors, and Matt pauses briefly to show me how they work. Select a movie from the touchscreen. Press play. The projectors run silent. Next to each one, you can see a rusty orange footprint where one of the old platters once stood.

During three summers of work at the theater, I had never before been allowed in the projection booth, and I had only seen Matt on the days he worked as a floor manager. Young, thin, and sullen, his main managerial duties seemed to be checking his watch, taking cigarette breaks, and sighing. But in the dim light of the projection booth, Matt is a changed man. He can thread a projector in three minutes flat, and he can do it with one hand. He’s memorized the projection schedule and starts each show on time to the second. He’s even figured out how to replace a faulty brain while its movie is running. Midway through explaining how to run two projectors from one print of film, he snaps to attention, then dashes off across the booth to wrestle with a platter in the early stages of brain wrap. “When you’ve spent enough time up here,” he explains breathlessly, eyes popped wide, “you get used to the sounds, and you can hear when something doesn’t sound right.”

Matt is training me how to do his job because the rise of digital projectors has suddenly made his job much easier. Day-to-day, a projectionist’s only responsibility is threading and starting the movies. This is a very complicated procedure, but it can still be taught by rote, and I am the proof. Back when the theater ran entirely on film projectors, it took a lot of skill to keep up with the schedule. But with digital projectors that essentially run themselves, those skills are no longer necessary. Word has come in from corporate to start eliminating projectionists and filling their shifts with floor staff like me. Once we complete the transition to digital, the booth will be abandoned entirely. Instead, the manager will run the movies with his mouse. Click click click click.

The booth isn’t so much a booth as a long hallway, mirroring the line of theaters below. On the ground floor, each screen feels distant from the screen across the hall, but in the booth, the two projectors sit so close you can reach out and touch them both at the same time. It’s as if the space of the theater has been condensed into a single line, a spine. Walking along its length, you can catch flashes of light and color on the screens below, each its own self-contained fantasy world, each world leading back to the booth.

Aside from six discarded film projectors, a different kind of salvage lines the long walls of the booth. A cardboard crowd of Hollywood actors and actresses jostles for position with aliens, robots, and singing chipmunks. All of the scowling and smiling faces are refugees from freestanding advertisements that once graced the theater lobby. The collection is impressive, but it’s packed densely around the start of the booth, where the projectors for the largest theaters sit. Those larger theaters are now serviced by digital projectors, and that end of the booth is shrouded in silence. In this silence, the frozen poses and cardboard grins take on a more sinister quality, and I am reminded of the projectionists who came before me. Back when the whole hall hummed with film, they lined the booth with the stuff of dreams; something to keep them company at night while they waited for the last reel to drop. But times have changed, and the poster people will soon have no one to keep company. The fake figures feel left behind, abandoned, a sort of human residue. Things can move very slowly in the booth, until–Matt snaps to attention–they suddenly move all too fast.

The intermittent sprocket, as its name might suggest, turns just once for every four turns of the other sprockets, but it’s easily the most important. While the intermittent sprocket lies dormant, the upper sprocket ticks off a frame of film, letting it gather just above the plate. Then, the intermittent sprocket engages, yanking the current frame off the plate and replacing it with the new one. As this happens, the shutter closes for a split-second to mask the switch. In the end, the audience sees only a series of still images and never the transitions between them. This is the fundamental illusion of moving pictures.

It’s my first shift alone in the booth, and I’ve completely lost it. I was trained under the assumption that everything would work perfectly, that nothing over the course of my six hour shift would slip, snap, or tangle. But the projectors and the platters weren’t designed to run perfectly; they were designed to run fast and dirty, under the watchful eyes of someone who knows how to fix them when they break. As long as people have sat in theaters and watched the movies, someone has sat behind them and watched the movies. From the old changeover systems, where the projectionist had to manually switch from one 20-minute reel to the other, to the present day, there has always been someone there to ensure that the show runs smoothly, and above all, that it starts on time.

As I reach again for my radio, I can feel that grand tradition slipping away. I’ve already called the manager upstairs twice, both times to sort out tangled fistfuls of film that had somehow escaped the brain and spiraled into chaos. I’ve since resolved to watch my brains closely, to always ensure that they are “thinking” (my own word for the action of the brain-arm). For my troubles, I’ve been hypnotized by the platter at Theater 7. My exhausted eyes turn along with the now-clockwise, now-counterclockwise spiral of the film. The strobe of the shutter flashes just on the edge of sight, and I listen carefully over the clicking sprockets for the faint sucking sound of film peeling off the main platter and starting its long journey to the projector. The radio on my belt breaks the reverie. “Andy…have you started 3 yet?”

I immediately jump up and sprint down the length of the booth, mumbling something vague into the radio. 3 was supposed to start 15 minutes ago; I must have been watching my brain for over 20. It’s a Wednesday afternoon, and nobody’s in the theater, but I’ve still failed an important test. This is the last projection shift I’ll be given for a long time.

Matt taught me the importance of always spinning the flywheel before working with the intermittent sprocket. The flywheel rotates along with the standard sprockets, but for a quarter of each cycle, it engages the intermittent sprocket too. This is how the sprocket can lie in wait for three clicks and spring to life on the fourth. Spinning the flywheel with your hand will rotate the intermittent sprocket manually and show you when it will turn in projection. You can line the first frame up perfectly, but if the intermittent sprocket fails to turn when you expect, it will spoil the whole rest of the movie, show the audience the gap between frames, ruin the illusion.

*click*

Forget everything about film being stored on gigantic platters. In the multiplex of the future, there is no film. This saves theaters time by eliminating the hassle of carrying, storing, building, splicing, threading, and untangling. Instead, movies are stored on thumb drives and downloaded onto a projector for the duration of their theatrical release. Of course, every solution carries along its own problems, and the problem with eliminating film from the projection process can be best illustrated by inserting plugs into your ears, then screaming. Instead of releasing you, the film just wraps tighter and tighter around your brain, and you have a gigantic mess on your hands.

Matt knows the exact date when he will turn off the lights for the last time and leave the booth to its army of grinning cardboard cutouts. Most of the other projectionists have already been forced out, but Matt has stayed on as a floor manager and trainer to the interim projectionists. He also works in the booth on weekends, when the stakes are too high to bring in a newbie. If he knows what’s good for him, Matt should be looking for another job, but I have my doubts that he is. I don’t know if he can feel the tension building up around him, or the forces gathering to yank him out of frame. Instead, he’s stuck listening to the click of the film and the hum of the bulb, and he’s not going to move until something finally breaks, or burns.